The Right Honourable Mary Simon aims to be an Arctic fox

Canada’s first-ever Indigenous governor general doesn’t play favourites among our majestic natural wonders, but she...

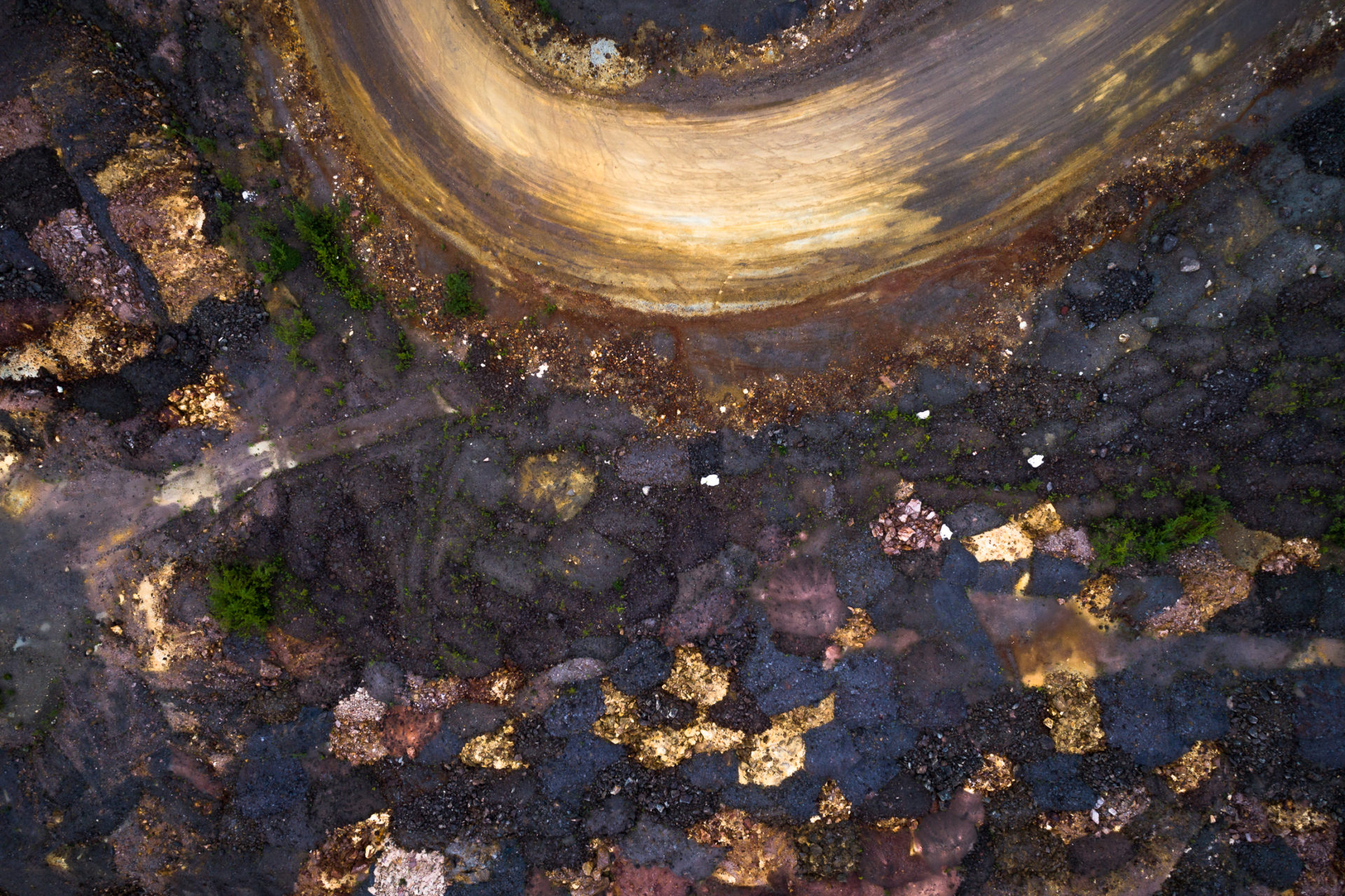

The Yukon’s giant Faro Mine was once the world’s largest open-pit lead and zinc mine.

In operation from 1969 to 1998, when its last owner declared bankruptcy, the mine once generated more than 30 per cent of the Yukon’s economic activity.

Now, Faro Mine is considered the second-worst contaminated site in Canada.

After nearly 20 years of maintenance and remediation planning, more than $350 million has been spent via the Federal Contaminated Sites Action Plan but remediation isn’t expected to begin until 2022.

Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada has released a timeline and draft details on the remediation plan for the Faro Mine and is currently seeking public input.

Remediation activity is currently expected to cost $500 million over 10 to 15 years. The biggest cost of remediation will be covering 320 million tonnes of waste rock and 70 million tonnes of tailings. Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada says the waste would cover 26,179 football fields, one metre deep.

Without remediation, the Pelly and Yukon Rivers could be polluted with toxic metals.

The Narwhal (then DeSmog Canada) sent photographer Matt Jacques to Faro to see the mine’s toxic legacy first-hand.

Home to more than 2,000 residents at the peak of the mine’s operation, the current population sits at 348, leaving many buildings and entire residential blocks unoccupied.

The Faro Mine occupies more than 25 square kilometres, roughly 25 per cent larger in area than the city of Victoria, B.C. At one point, it was the world’s largest open-pit lead/zinc mine.

In addition to this primary mine, there are two smaller open-pit mines on site.

Mine operations left behind more than 320 million tonnes of waste rock and 70 million tonnes of tailings before the mine’s final closure in 1998.

Adjacent to the mine site, Rose Creek winds through a wetlands ecoystem that feeds the Pelly River.

The Faro Mine remediation consultation and planning process continues, with a plan to be finalized prior to the project being submitted to the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board (YESAB) in 2018.