Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

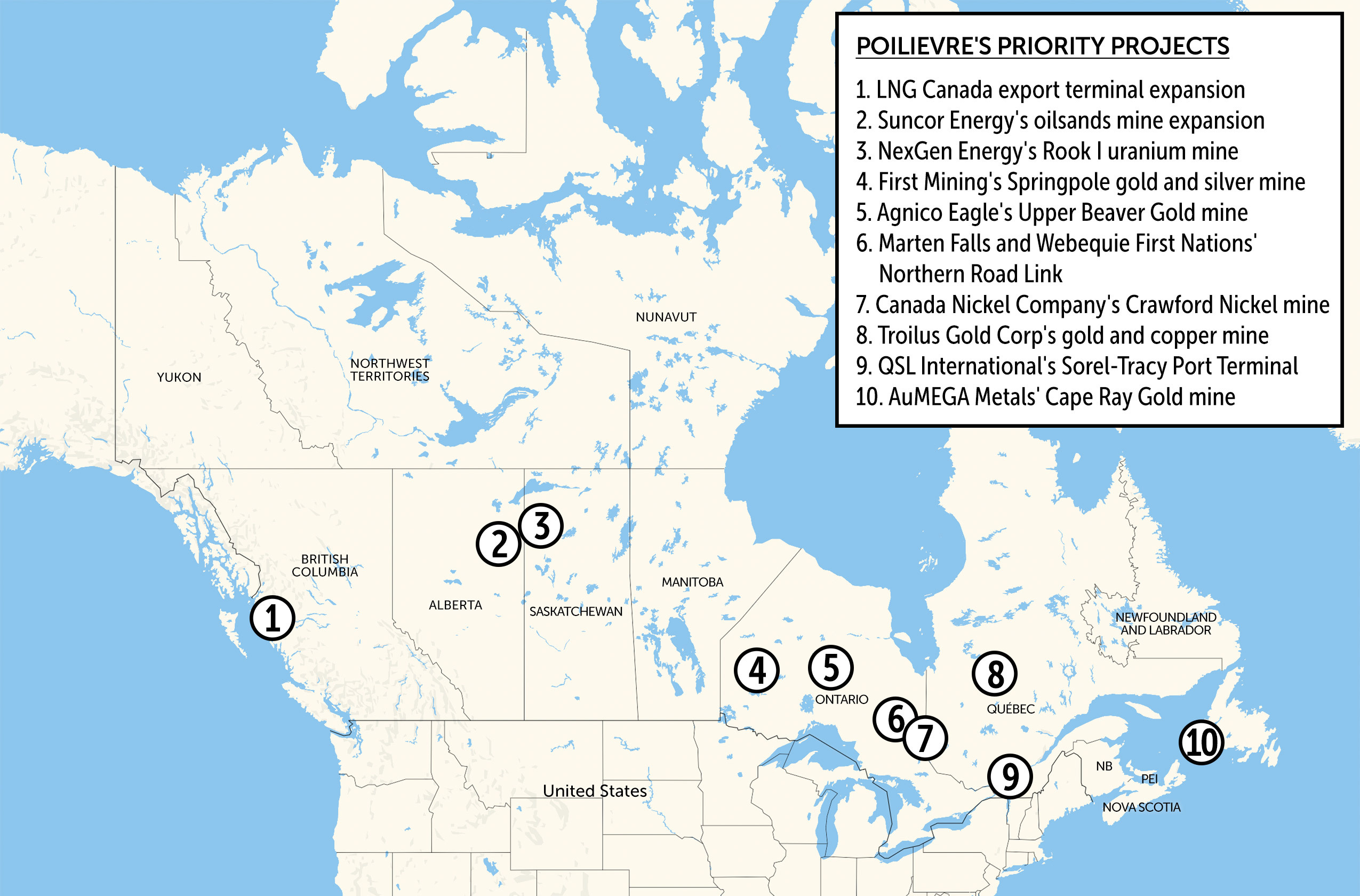

Pierre Poilievre says a slew of new oil, gas and mining projects in Canada have been “stuck for years” awaiting federal approval. The reality is more complicated.

Poilievre, the leader of the Conservative Party of Canada, said this month that if elected his government would “rapidly approve” 10 natural resource and infrastructure proposals he claimed have been held up in the “slow federal approval process.”

They include an LNG plant expansion in B.C., an oilsands mine expansion in Alberta, a uranium mine in Saskatchewan, a road in Ontario, a port in Quebec and five mines among Ontario, Quebec and Newfoundland and Labrador that would produce gold, silver, copper and nickel.

Poilievre said, if the Conservatives gain power following the April 28 federal election, the government would “find the holdups and accelerate federal decisions to get industry moving, workers working and dollars flowing back to Canada.”

An analysis of the 10 projects by The Narwhal shows it is not always the federal government holding things up. One project has already been fully approved and permitted, but is awaiting a business decision before proceeding, while two are nearing the final stages of approval. In another case, a member of a project’s advisory committee told The Narwhal she had heard the company itself had recently asked for an extension during the assessment process.

Meanwhile, another project is facing questions over how it will ensure Indigenous Rights are respected, wildlife is protected and environmental impacts are properly managed, and has been opposed by a nearby First Nation.

Often in federal assessments, “companies don’t do their homework” on things like habitat protection, which can delay timelines, according to Jamie Kneen, national program co-lead at MiningWatch Canada. Projects can also stall, he said, if investors decide to wait for better market conditions before jumping in.

“It’s not the environmental assessment law and the process that slows projects down,” Kneen said.

Poilievre said he would “work with proponents and First Nations” to approve the projects. That is already part of the mandate of the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada, which consults with Indigenous Peoples, seeks public input and reviews projects for impacts on Indigenous Rights, species at risk, fish and migratory birds.

Poilievre has said he would repeal the law that establishes the agency and allows the government to order those reviews.

The Mining Association of Canada, a lobby group that represents three of the companies proposing projects on Poilievre’s list, said it has been asking for improvements to regulations that result in timelier decisions.

“It is possible to shorten timelines without compromising environmental oversight, social responsibilities or the meaningful involvement of Indigenous Peoples,” Paul Hébert, the association’s vice-president of communications, told The Narwhal.

But he added the government has already made some improvements “that signal that efforts are underway to address inefficiencies.” As a result of a Supreme Court of Canada ruling, the government amended the Impact Assessment Act in 2024 to focus it on areas of federal jurisdiction.

Asked how the group felt the government should handle issues like species at risk, or Indigenous Rights, if there was no longer a federal assessment law, Hébert pointed out mining projects were still subject to “comprehensive provincial regulatory frameworks.”

The Liberal Party of Canada has also proposed a “one window” process for approving large projects that it says would work closely with provincial assessments to avoid redundancy.

But Linda Heron, chair of the Ontario Rivers Alliance, a non-profit focused on river systems, noted the Ontario government’s significant changes to its own environmental assessment regime has already attempted to “streamline” the process.

While the Ontario government said its changes would not harm the environment, Heron said it “totally gutted our environmental protections and any assurance of public participation in these projects,” forcing them to rely on the federal assessment process that Poilievre is now vowing to repeal and Liberal Leader Mark Carney says can be shortened.

A spokesperson for the impact assessment agency declined to comment on Poilievre’s list of priorities. Poilievre’s team did not respond to a request for comment.

At the top of Poilievre’s list is the second phase of a B.C. liquefied natural gas export plant, called LNG Canada.

The facility in Kitimat, which is fed by the Coastal GasLink pipeline, is expected to be fully operational and begin shipping LNG this year. It will be the first large LNG export facility in Canada, and the company hopes to supply gas to overseas markets.

The second phase, which could come as early as 2030, is expected to double production, creating around 13 million tonnes of carbon pollution each year. Poilievre claimed this second phase “faces power supply challenges and output limitations related to the emissions cap.”

But the federal government has already approved the second phase, and LNG Canada has been permitted to run its entire operation with gas-powered turbines, so it’s not restricted to using low-carbon electricity.

The project also gets to sidestep provincial net-zero requirements, B.C. Energy Minister Adrian Dix confirmed. As for a federal emissions cap, such a policy has only been proposed and is not in force.

The five-member consortium backing the project has yet to make a final investment decision to proceed.

Similarly, Poilievre singled out the Rook 1 Project, an underground uranium mine in northwest Saskatchewan, proposed by Vancouver-based NexGen Energy. That project is already approaching the final stage of approval, according to a company press release.

It said it had received a thumbs up from the province and cleared a federal technical review and impact statement, and the last step is for Canada’s nuclear safety commission to hold hearings in the fall and winter.

Along the way, the province had identified “environmental and technical issues” it said “required revisions and additional clarification before the assessment process could proceed.”

Travis McPherson, chief commercial officer for the project, told The Narwhal he didn’t think those issues had any bearing on the time taken for a federal assessment.

Nevertheless, he agreed with Poilievre that the project had been stuck awaiting federal approval. “Undeniably yes,” he said.

“We support his position on our project given all reviews have been completed, the province already fully approved it in 2023 and all Indigenous nations impacted by the project have endorsed, strongly, its immediate approval.” (A press release from the Clearwater River Dene Nation said the project was “formally endorsed” through impact benefit agreements “by all of the Indigenous communities in the project area.”)

Toronto-based Canada Nickel Company’s Crawford Nickel Project, an open-pit nickel-cobalt mine and metal mill north of Timmins, Ont., was also identified on Poilievre’s list.

It, too, appears to be “in the final approval stage with the federal government,” according to a March interview with the company’s CEO by a financial analysis publication. The company has said it expects approvals this year and has secured financing partners including Scotiabank.

The Ontario Rivers Alliance said in February it was “concerned with the serious lack of details” in the company’s documentation about the project’s effects on things like downstream ecosystems.

LNG Canada and Canada Nickel Company did not respond to requests for comment.

In northeastern Ontario, near the town of Kirkland Lake, Poilievre has pinpointed an open-pit and underground gold and copper mine, and on-site metal mill, proposed by Agnico Eagle.

The Upper Beaver Gold project, which could produce 15,000 tonnes of ore per day, will require diverting more than 90 million cubic metres of water from nearby Beaverhouse Lake, into the Misema River, each year.

In December 2024 the federal assessment agency said it hoped the company would give “specific focus and attention” to “the loss or alteration of fish habitat” as well as other impacts.

The agency also had questions about water quality, contaminants, migratory birds and Indigenous traditional use of lands and resources.

Heron, the Ontario River Alliance’s chair, is a part of the advisory committee for the Upper Beaver Gold project and told The Narwhal it should be moving into the impact statement phase, where the proponent gathers all pertinent information and studies into a technical document for the assessment agency to review.

She said she has been waiting for this document since 2022, but she had heard the proponent is now seeking a time extension to 2026. (The impact assessment agency’s website does not appear to contain this request and a request for comment to the company was not returned.)

“It is not environmental advocates dragging out the process,” Heron said.

The Ontario Rivers Alliance says it’s concerned about the “potential cumulative environmental effects on the air, land, water and wildlife” in the area.

Poilievre also said he wants to approve the Springpole Gold Project, an open-pit gold and silver mine and ore processing plant, proposed by Vancouver-based First Mining Gold Corp., in Ontario’s northwest.

First Mining Gold’s CEO recently said the company hopes to finish the environmental assessment process by the end of this year.

The project has faced questions about its plan to drain a lake and what effect that might have on lake trout, and the ability of the community of Cat Lake First Nation northeast of the project to harvest fish.

In November 2024, Cat Lake Chief Russell Wesley said the community opposed Springpole Gold. The company says it is working with First Nations “to continue to advance meaningful dialogue.”

In February the federal assessment agency also told the company it had “insufficient information” on fish and fish habitat, as well as migratory birds and impacts on Indigenous Peoples. In another letter, it indicated a species at risk permit would “likely be required.”

The company’s 2023 sustainability report said it has studied lake sturgeon to evaluate the potential of “species re-introduction” and that it hoped to collaborate with government and Indigenous communities on “habitat offsetting initiatives for fish and caribou.”

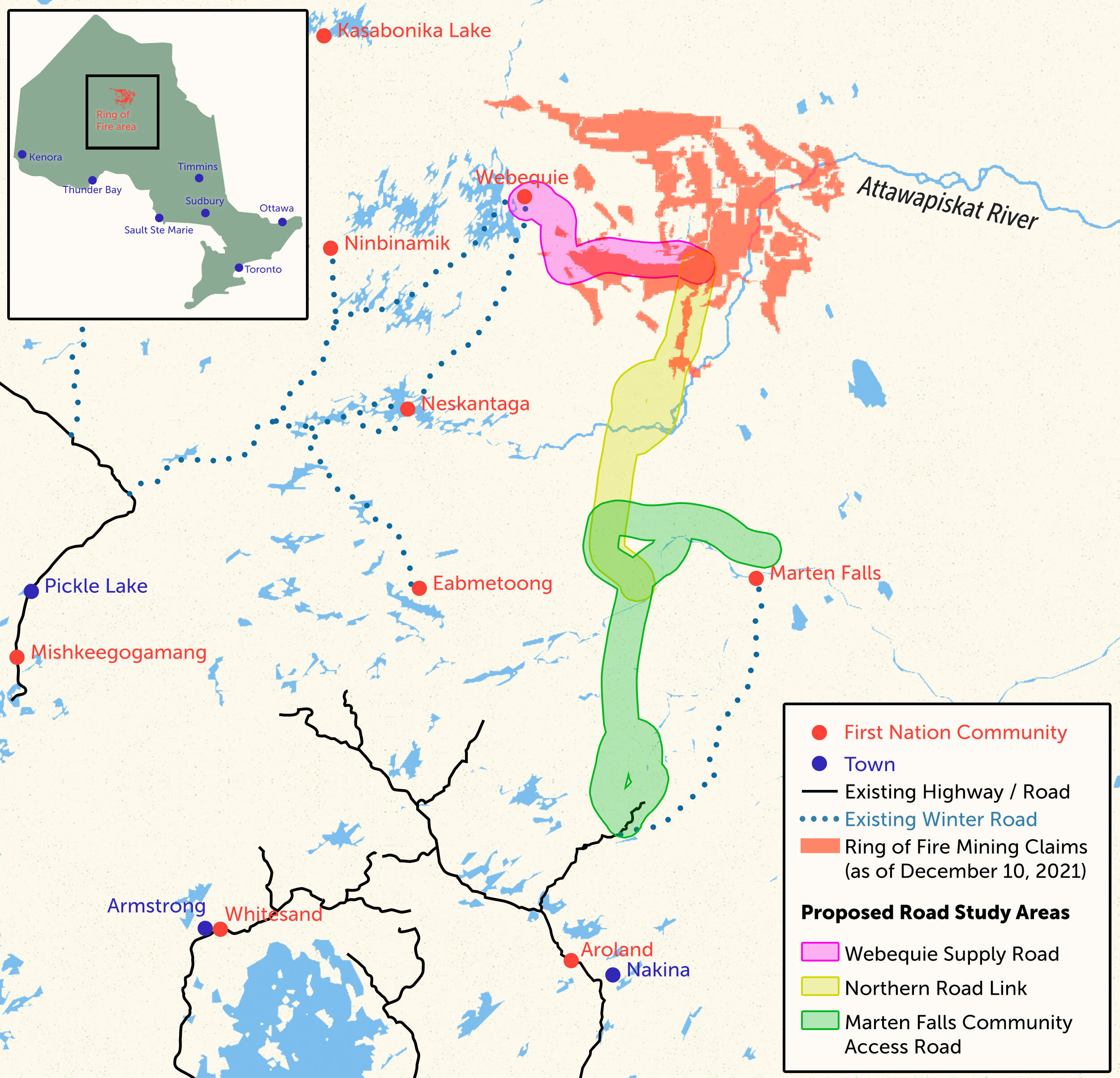

An all-season road project to connect the mineral-rich Ring of Fire in northern Ontario to the province’s highway network also made Poilievre’s list. Proposed by Marten Falls First Nation and Webequie First Nation, the Northern Road Link would connect two other proposed roads in the north in order to access the area that’s been heavily touted in the push for critical minerals. Several First Nations in the area have voiced concerns about proper consultation for the Ring of Fire, and the impact mining would have on the environment.

Agnico Eagle, First Mining Gold and the Northern Road Link group did not respond to requests for comment.

Poilievre also wants to see Suncor’s Base Mine extension, a proposed open-pit oilsands mine, approved. The mine would span 30,000 hectares — just under half of the size of Edmonton — and supply much more bitumen, a tar-like petroleum substance, to oilsands processing plants.

In 2020, Suncor submitted a plan to the government for the mine, but the company also said at the time it didn’t expect operations to begin until 2030, and its existing base mine would still be in operation for roughly another 15 years.

Meanwhile, then-environment minister Steven Guilbeault warned the company in 2022 that, because the mine would produce an estimated three million tonnes of carbon pollution annually, he might not approve it as it would not align with the government’s climate targets. Poilievre has not committed to a specific climate target.

Two other mines — the Troilus Mining project, an open-pit gold and copper mine proposed by Troilus Gold Corp. in northern Quebec, and the Cape Ray Gold Project, an open-pit and underground gold and silver mine and mill, proposed by AuMEGA Metals in western Newfoundland, are on Poilievre’s list.

He also identified the Sorel-Tracy Port Terminal, a new port and floating wharf proposed by QSL International Ltd. near Sorel-Tracy, Que., along the St. Lawrence River.

Suncor, Troius Gold, AuMEGA Metals and QSL International did not respond to requests for comment.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...