Battling a hungry beetle, this Mohawk community hopes to keep its trees — and traditions — alive

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

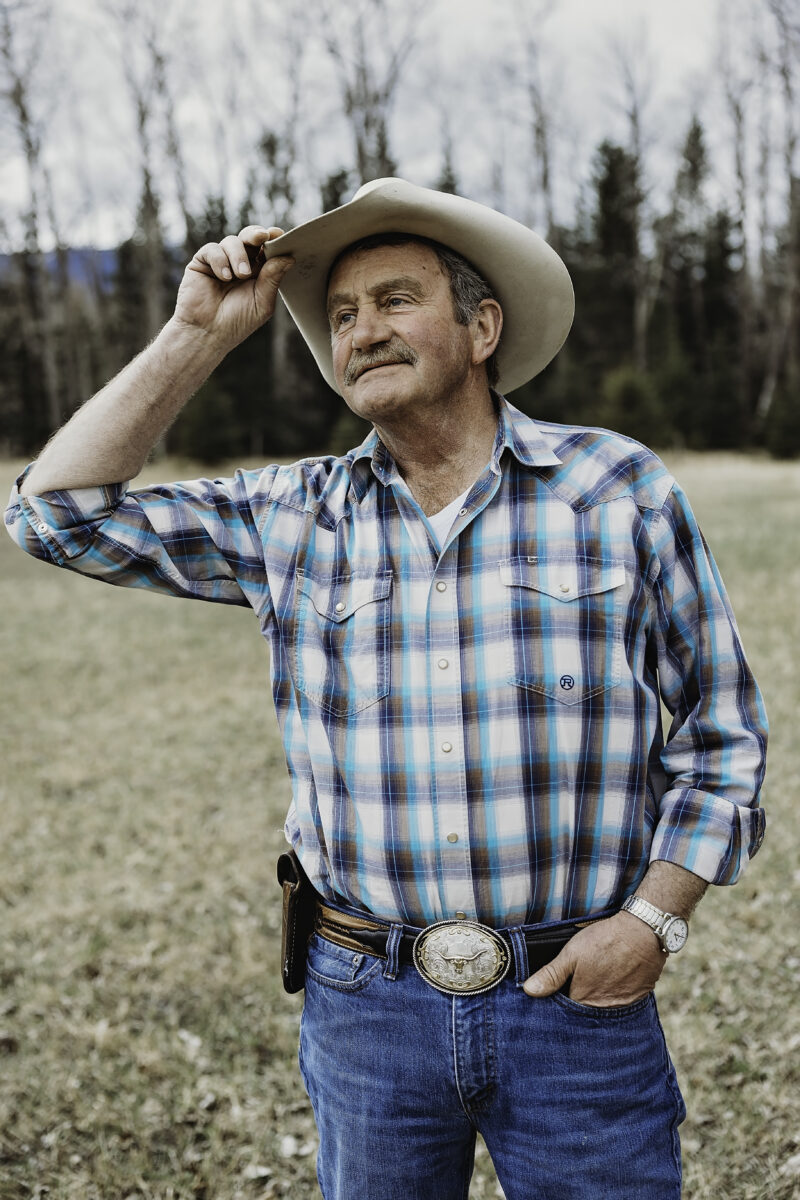

Dave Salayka has been a professional forester and tree faller for most of his working life. He’s laid out cutblocks, worked in Alberta’s oilsands and is part of a crew clearing the right of way for the Trans Mountain pipeline. But the rare inland temperate rainforest in British Columbia’s Raush Valley — home to 1,000-year-old cedar trees, moose and grizzly bears — is one place Salayka doesn’t want to see logged.

Salayka, a long-time resident of Dunster, in B.C.’s central interior, is joining forces with local ranchers, business owners and conservationists to try to save the old-growth Raush Valley, 250 kilometres southeast of Prince George, from planned clear-cutting that would entail building a logging road through a provincial protected area.

“It’s a pristine valley,” Salayka tells The Narwhal. “It’s wilderness. We still have every wild creature … There’s huge biodiversity. It’s completely representative of wild places, and there are very few of them left on the planet.”

“It’s such a waste to take trees that are hundreds and thousands of years old and turn them into lumber.”

The glacier-fed Raush River, flanked by the northern Columbia Mountains, is the Fraser River’s largest undeveloped and unprotected tributary. Its name is an abbreviation of Rivière au Shuswap, drawn on early maps as R.au.sh, referring to the Secwépemc or Shuswap peoples who have lived in the region for millenia. The valley contains four different biogeoclimatic subzones, the rarest of which is dominated by a cedar-hemlock forest known as the inland temperate rainforest.

B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest is scattered in moist valley bottoms stretching from the Cariboo Mountains to the Rocky Mountains. Other temperate rainforests, far from the sea, are only found in two other places in the world, in Russia’s far east and southern Siberia.

Thousands of years ago, coastal species like cedar and lichens hitchhiked to the interior as seeds and spores, flourishing undisturbed in the sheltered dampness of valleys that kept fire at bay. Today, some of the oldest trees in the inland temperate rainforest are as ancient as their coastal big tree cousins, which generally command a much larger share of public attention.

Dave Salayka, who has been a tree faller and professional forester for most of his working life, doesn’t want to see logging in the Raush Valley. The valley is home to old-growth cedar and hemlock and is a haven for wildlife, including lynx, wolverine, grizzly bear, caribou and mountain goat. Photo: Katharina McNaughton / The Narwhal

In 2005, following a land use planning process, the B.C. government designed a protected area at each end of the Raush Valley, a wildlife corridor that connects Wells Gray Provincial Park to the Fraser River watershed. Together, the two protected areas, called the Upper Raush and the Lower Raush, cover about one-fifteenth of the 100,000-hectare valley. Most of the valley, spread out between the two protected areas, remained open to industrial logging but nothing has happened until now.

Logging rights to the Raush are held by Carrier Forest Products Ltd., a B.C.-based company with mills in Prince George and Saskatchewan. Carrier can only access its Raush Valley tenure through private ranch land or by building a logging road through the 1,280-hectare Lower Raush Protected Area, a piece of land about the size of three Stanley parks that provides valuable riparian wildlife habitat.

The Raush Valley is 250 kilometres southeast of Prince George. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Any road through the protected area would also have to run through a privately held grazing lease for horse and cattle.

Devanee Cardinal, whose family owns the grazing lease and 600 hectares of ranch land at the mouth of the Raush River, says family members will not grant Carrier access to their adjoining properties, where four generations have lived since her grandparents homesteaded in the 1960s.

“When I grew up, the ranchers were not environmentalists,” Cardinal says in an interview. “It was very black and white. There were the loggers, and then there were the tree huggers. Now it’s not really like that. There’s hardly anyone who doesn’t recognize that the Raush has this unique ecological blueprint that is undisturbed — and that is now becoming so rare within B.C. The loggers recognize that, locals recognize that and we as ranchers recognize that too.”

JD Cardinal is Devanee Cardinal’s son. Four generations of the family have ranched on land at the mouth of the Raush River. A proposal to log the intact valley would entail running a logging road through the family’s grazing lease and a provincial protected area. JD, who runs 100 head of Angus cross cattle, says logging would open up the intact valley to lots of people and hunting. “Ecologically, I think it’s going to have a huge impact on the land and old-growth. It’s a protected area for a reason. I’m not a tree hugger or a greenie or anything. But they’ve logged the piss out of every other side valley here [in the Robson Valley]. The Raush is the most unique place in the valley.” Photo: Katharina McNaughton / The Narwhal

The Raush Valley lies in the territory of Simpcw First Nation, Lheidli T’enneh First Nation and the Canim Lake Indian Band.

In an emailed statement, Kerri Jo Fortier, natural resource department manager for Simpcw First Nation, said the nation does not support cutting permit applications in the Raush Valley and that adequate consultation has not occurred. The Narwhal reached out to the other nations but they were unable to respond by press time.

Rancher Rodger Peterson, who is Devanee Cardinal’s uncle, describes the Raush Valley as a fragile ecosystem with fir, pine, balsam spruce and cedars so old it would take three or four people to encircle them with arms outstretched. The valley is home to a plethora of wildlife, including at-risk species such as mountain goat and fisher, a fierce mustelid that dens only in old trees.

“I’ve travelled extensively throughout the province, and I’ve seen a multitude of valleys,” Peterson says. “I would challenge anyone to come up with one as unique as this valley. And I suspect if they could, it may already be preserved and if it’s not, people don’t know about it.”

Peterson says he only learned about Carrier’s intention to log the valley from the local newspaper and is disappointed that he and other stakeholders were not notified directly. “They’ve started right off by excluding information that the public may be interested in knowing.”

Rodger Peterson on his ranch near McBride, B.C. Peterson’s family, who have ranched in the area since the 1960s, is opposed to planned industrial logging in the old-growth Raush Valley. Photo: Katharina McNaughton / The Narwhal

Rob Mercereau along the Raush Valley Road. Mercereau, who co-owns a small portable sawmill, is among the Dunster residents who don’t want to see industrial logging in the intact Raush Valley. Photo: Katharina McNaughton / The Narwhal

In an emailed response to questions, B.C.’s Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy confirmed that Carrier applied for an investigative parks use permit on March 19 to explore potential road options in the Lower Raush Protected Area.

The ministry said Carrier will gather data for an assessment, which will include an inventory of plants along the proposed logging road and offsets for any values potentially lost in the area. If the investigative parks use permit is approved, the information will be used to support a parks use permit application for a road, the ministry stated.

Normally, parks use permit applications are public, but the ministry said Carrier’s application has not been posted because staff are still reviewing it. The ministry could not say if there have been any other parks use permit applications to build logging roads through provincial protected areas.

A Carrier Lumber map shared with The Narwhal shows the proposed logging road will cut through the lower protected area on the west side of the glacier-fed Raush River, to log a pie-shaped section of inland temperate forest wedged between the river and the boundary of the protected area.

“How is it protected if the logging can go through the grazing lease, through the protected area and they can still haul logs out of there?” Cardinal asks. “To me, that means it’s not really protected.”

The Carrier map also shows cutblocks in patches throughout the valley. The logging road cuts through the valley, then hairpins west to cut blocks that adjoin the

Upper Raush Protected Area, which provides critical habitat for the endangered Wells Gray southern mountain caribou herd.

According to the 2005 Raush protected areas plan, the alpine and subalpine areas of the Raush River are extremely important for mountain goat populations, while the valley bottom offers important winter range for moose and deer and summer range for bear and other species. Salmon spawn several kilometres downstream from the Lower Raush Protected Area and native fish species such as bull trout, rainbow trout and mountain whitefish are found within both protected areas.

In its email, the B.C. environment ministry pointed to the 2005 purpose statement and zoning plan for the Upper and Lower Raush protected areas, which allows for “future forestry road access.” The 2005 plan also says the protected areas will be reclassified as parks when the road corridor “is no longer necessary.”

But that’s no comfort for Cardinal and other local residents like Rob Mercereau, who lives in Dunster and co-owns a small portable saw mill.

“I’m adamantly opposed to them building the road through the protected area,” Mercereau says. “I’m opposed to them gaining access to the valley at all.”

He points to the contiguous park system in the interior that includes Wells Gray Provincial Park, Caribou Mountains Provincial Park and Bowron Lakes Provincial Park, noting the Raush is the only valley and watershed to connect the parks system to the salmon-bearing Fraser River.

“No other place in the Fraser watershed connects completely,” Mercereau says. “That alone to me would signify a need to protect it. We need to have those wildlife corridors if we have any hope for the future of wildlife in northern B.C.”

Dunster resident Rob Mercereau believes the old-growth Raush Valley should be left intact and is opposed to the construction of a logging road through a provincial protected area. Photo: Katharina McNaughton / The Narwhal

Carrier president Bill Kordyban says the company understands the concept of social licence and is happy to talk to local residents and come up with a plan that works for everybody.

“On the other hand, I have a sawmill that needs wood and when we bought the timber licence the Raush was part of the timber supply base,” Kordyban says in an interview. “We have obligations to get in there and to do some harvesting. We should do it in a way that doesn’t upset too many people … but to say leave it totally alone, well that, de facto, makes it a park.”

The company hopes to begin road-building in the lower part of the Raush Valley late this year or early next year, depending on the permitting, and proposes to cut just over 100,000 cubic metres of wood over the following two to three years. After that, Carrier’s operations would shift to the upper part of the valley, taking out approximately another 500,000 cubic metres of wood over a 10 to 15-year period, Kordyban says.

Spruce, pine and fir will go to the company’s dimensional sawmill in Prince George, while the cedar will be shipped locally to BKB Cedar Manufacturing in McBride and Cedar Valley Specialty Cuts in Valemount and as far away as Gilbert Smith Forest Products Ltd., in Barriere, north of Kamloops. The hemlock will be taken to a new mill owned by the Valemount Community Forest.

“We try to find homes for all the species,” Kordyban says.

A sawmill near Prince George. Carrier plans to send lumber from the Raush Valley to its dimensional sawmill in Prince George. Carrier president Bill Kordyban says the cedar will be shipped locally to BKB Cedar Manufacturing in McBride and Cedar Valley Specialty Cuts in Valemount and as far away as Gilbert Smith Forest Products Ltd., in Barriere, north of Kamloops. Hemlock will be taken to a new mill owned by the Valemount Community Forest. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

Carrier’s application comes as the BC NDP government drags its heels on implementing recommendations from an independent old-growth strategic review panel it commissioned in 2019. The panel, led by foresters Al Gorley and Garry Merkel, made 14 recommendations that the BC NDP promised to implement during last fall’s provincial election campaign if re-elected.

In the April 12 Speech from The Throne, which lays out the government’s blueprint for the current legislative session, the NDP government appeared to backpedal on its election promise, saying only that it will “continue to take action on the independent report on old growth.”

Critics assert that very little has been done, with the Ancient Forest Alliance and two other conservation groups assigning the government a failing grade in a recent report card that examined progress on implementing the panel’s recommendations, submitted to the government one year ago.

In one recommendation, Gorley and Merkel said the government should immediately defer development in old forests “where ecosystems are at very high and near-term risk of irreversible biodiversity loss.”

“If I were the forests minister, I would be conserving old-growth,” Salayka says. “If I were [John] Horgan as the premier I’d be saying ‘We’re going to phase out logging old-growth, because it should be conserved.’ It’s more valuable standing for all the values it provides. We do have second growth forests that can be logged, but old-growth takes centuries to grow.”

Dave Salayka is a professional forester who lives in Dunster, B.C. “It’s such a waste to take trees that are hundreds and thousands of years old and turn them into lumber,” he told The Narwhal. Photo: Katharina McNaughton / The Narwhal

Kordyban says Carrier will work with any new rules for old-growth logging implemented by the province, pointing out that the old-growth strategic review panel’s recommendations are still just a plan.

“There’s been a commitment by the government that they’re going to implement it. The devil is always in the details. We’ll live by whatever the rules become.”

He says the government ought to designate areas of working forest where a primary goal is timber production, instead of the current “piecemeal” approach.

“Then we can avoid situations like what’s happening in Fairy Creek or here, when a company starts to develop an area and then ‘nope nope, you can’t.’ Because then we go on a valley by valley basis. It’s not good for anybody. It would be nice to have some certainty. What is the working forest? What areas are protected? What areas are off limits? Once and for all, it would be nice to delineate what can be done [and] where.”

Michelle Connolly, director of Conservation North, a science-based non-profit group based in Prince George, says the Raush Valley is among the areas in the province at the highest risk of biodiversity loss that Gorley and Merkel recommended be immediately deferred from logging. Logging will target the high-value old-growth first, Connolly notes.

“It’s a true wilderness area. It’s intact. As far as I understand it’s never had any kind of industrial activity in it. There’s been hunting in it, there’s been traditional use in it. I’ve seen aerial photos of a deeply incised wild valley with a river running through the middle. It looks heartbreakingly beautiful. We have so little of this in the central interior. We have to keep it for nature because the rest of our region has really become sacrifice zones.”

Michelle Connolly, the director of the science-based group Conservation North, sits in a burnt slash pile in B.C.’s interior. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

A 2020 independent study by B.C. ecologists who previously worked for the provincial government found that less than three per cent of the province’s old-growth remains.

In January, Conservation North released an interactive map that reveals what little remains of B.C.’s original and ancient forests, depicting logging and other industrial human activity as a vast sea of red.

Conolly calls roads into wilderness areas like the Raush the “beginning of the end.”

“If you allow a road to get punched through an area it’s vulnerable to a lot of things. You get a lot of motorized recreation. You get more people, you get risks of fire. You get invasive species potentially. You get habitat fragmentation.”

B.C.’s old-growth forest nearly eliminated, new provincewide mapping reveals

But Kordyban says another way to look at things is that the company will be providing public access to an area that has been relatively inaccessible because the current road access is private.

“If we were forced to walk away from the Raush, what we’d need to do is then say, ‘okay, where can we go?’ Part of the reason why we’re looking to develop the Raush is because there’re so many constraints on the land base from a forestry perspective.”

Roy Howard, president of the Fraser Headwaters Alliance, says there are many compelling reasons to leave the Raush Valley intact and wild.

“Any old growth in the province at this point is becoming extremely valuable for carbon retention, for wildlife habitat, for water values,” Howard says. “It’s a big wilderness, which we’re losing all the time. I think we want to hang onto the wilderness values as much as we can but also the old-growth values. It’s incredibly important for carbon [storage] to leave those old forests intact as much as we possibly can.”

UBC researchers have found that B.C.’s inland temperate rainforest is one of the wettest zones in the province and has the highest diversity of tree species. The inland temperate rainforest also stores high amounts of carbon in its forests and is exceptionally important for freshwater provision, in addition to being a hotspot for nature-based outdoor recreation.

The cedar-hemlock forests that characterize the rainforest have the highest density of overlapping carbon storage and freshwater provision hotspots in the province, the researchers found. “This makes the region a high priority not only to protect this globally rare ecosystem, but to secure fundamental needs for people,” says an April brief on the research published by the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative.

“When it comes to the Raush, it’s not possible to overstate how much is at stake,” Connolly says. “We’ve violated so much of the land in the central interior. We can’t let that happen in the Raush. If we lose the Raush, we’ll have lost ourselves.”

The environment ministry said parks use permit applications are subject to public and Indigenous consultations and the time span for conducting the work for both parks use permits could take 18 to 24 months.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...

As the top candidates for Canada’s next prime minister promise swift, major expansions of mining...