‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

The mood was sombre at a Wet’suwet’en camp and village site near the confluence of Ts’elkay Kwe (Lamprey Creek) and Wedzin Kwa (Morice River) in the early afternoon on March 29. A group of Wet’suwet’en chiefs, community members, land defenders and their supporters wrapped up a debriefing meeting after five people were arrested and taken off the territory by the RCMP. Then someone cracked a joke and the mood lightened.

“It must annoy them to hear us laughing,” Dinï ze’ (Hereditary Chief) Na’moks chuckled.

That morning, land defenders at the camp watched as a convoy of RCMP vehicles pulled up outside the fenced-off area, according to community members. More than a dozen officers filed through the gates and said they were there to conduct a search, under a warrant issued by the B.C. courts, land defenders told The Narwhal.

“I’m going to ask everyone to leave the area so we can conduct a safe search,” an officer said, according to video footage shared with The Narwhal. “Anyone who refuses to leave the area will be arrested for obstruction,” he added, handing out copies of the warrant. “I’m not going to tell you guys 17 times that you need to leave, so …”

“We need to talk to our lawyer,” one land defender interrupted.

“No, that’s not how this works,” the officer replied.

The land defender insisted they should be given 15 minutes to talk to their lawyer to confirm the warrant was “legit” but the officer said police were not required to provide any time. Staff Sergeant Kris Clark, senior media relations officer with the RCMP, told The Narwhal there was no obligation to provide access to legal counsel prior to the search. After a few seconds and a brief back-and-forth exchange, several officers moved in and started the arrests.

Among those arrested and taken to the Houston, B.C., RCMP detachment was Jocey Alec, daughter of Dinï ze’ (Hereditary Chief) Woos. Several hours later, after being released, she showed The Narwhal her wrists, marked and bruised from the zip tie handcuffs. She said the arresting officer initially put them on too tight, making her hands go numb. Another land defender said they were punched in the head while on the ground, and showed a bruise on their right temple.

Clark, with the RCMP’s media relations, said he was unable to speak to specific allegations but noted there are processes available for those who wish to file a complaint. According to an RCMP statement, four individuals were arrested for refusing to cooperate with police direction and one for attempting to prevent officers from executing the warrant.

“Any allegations of misconduct by the RCMP are taken seriously and will be investigated fully,” Clark told The Narwhal in an email. “I can say that the search and arrests were captured on video which will constitute part of the disclosure for court purposes.”

The area, about 50 kilometres south of Houston, B.C., has been the site of numerous clashes between Wet’suwet’en land defenders, police and industry workers building the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

The pipeline is being built to connect shale gas sources in the province’s northeast with two liquefaction and export facilities in Kitimat — LNG Canada and Cedar LNG. It crosses about 190 kilometres of Wet’suwet’en territory. Five of six elected band councils signed agreements with the company and the province in support of the project but the hereditary leadership remains opposed. RCMP have made nearly 100 arrests over the past four years, during conflicts related to the pipeline project.

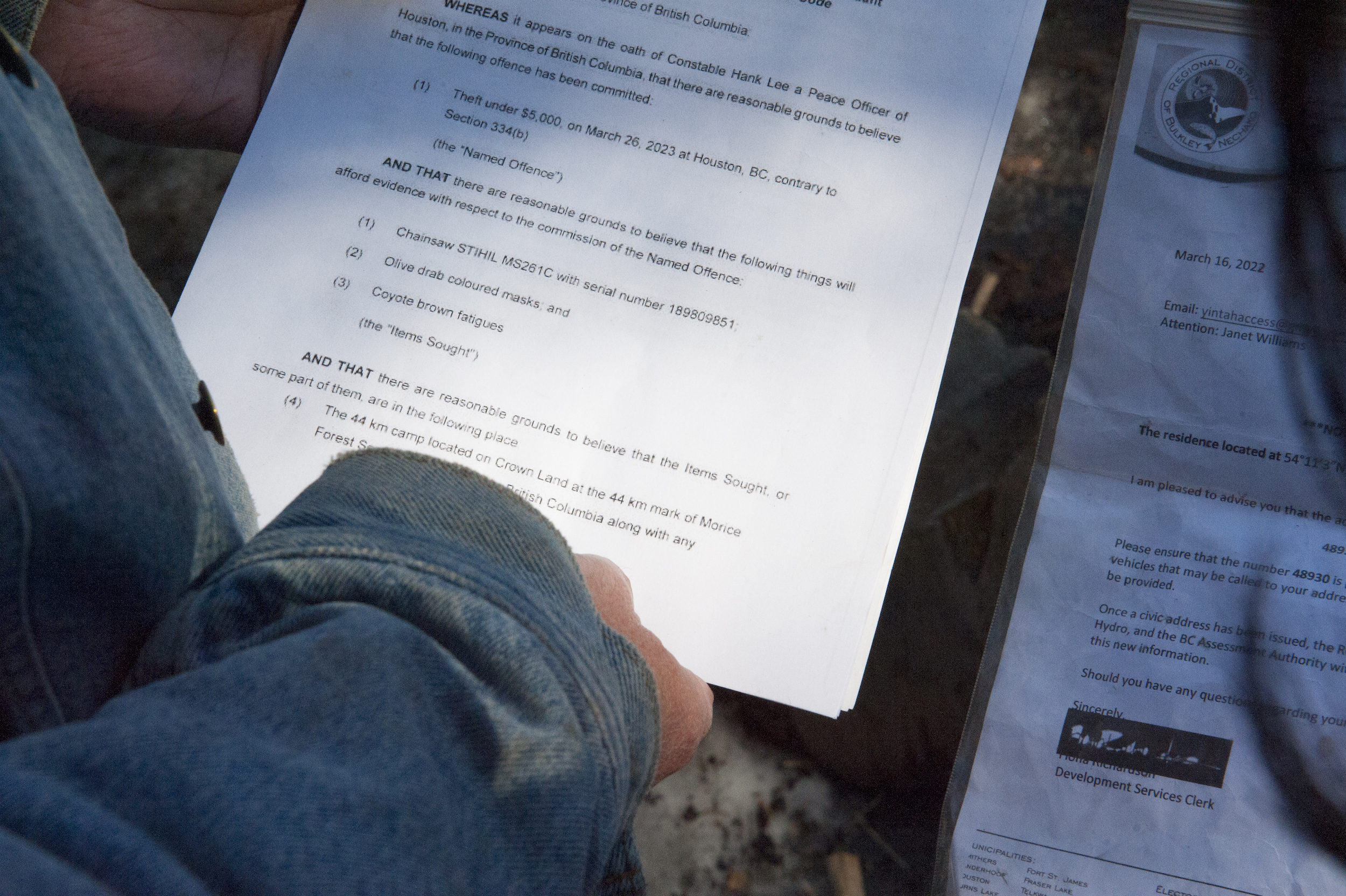

According to the RCMP statement published following the March 29 arrests, the search was related to an incident that had happened a few days earlier, in which local police received a complaint from a Coastal GasLink security worker. The worker alleged a group of individuals wearing masks and camouflage “fired flares and gained access to the work vehicle when the worker left the area because of the intimidation” at just before midnight on March 26. The police statement added, “these persons allegedly poured liquid onto the vehicle and stole a chainsaw from the truck bed.”

TC Energy, the pipeline operator, declined an interview request and referred The Narwhal to the RCMP for more information.

“We are thankful that no one was injured during this incident,” a TC Energy media spokesperson wrote in an emailed statement. “We will continue to cooperate with the Houston RCMP in their investigation of this and, as always, will prioritize the safety of our work crews and the communities around us.”

The search warrant, issued for theft under $5,000, noted the courts agreed with a Houston RCMP officer that a chainsaw, “olive drab coloured masks” and a pair of “coyote brown fatigues” had been stolen and there were reasonable grounds to believe those items would be found in the Gidimt’en camp.

Na’moks said he was not previously aware of the March 26 incident and questioned why anyone associated with the Gidimt’en camp would have cause to steal equipment, noting the camp is outfitted with numerous tools.

“Why would anyone here steal a chainsaw?” he asked, pointing to a line of chainsaws in an outbuilding.

The RCMP did not indicate whether they had retrieved any of the items during the search.

“The results of the search are subject to the investigation and no further details are being released at this time,” Clark wrote.

According to the wording of the search warrant, the Gidimt’en camp is on “Crown land.”

To Dinï ze’ (Hereditary Chief) Gisday’wa, who drove out to the location when arrests were underway, it’s a moot point.

“There’s no such thing as Crown land in Canada,” he told The Narwhal in an interview. “It belongs to us, the Natives.”

In 1997, the Supreme Court of Canada affirmed the Wet’suwet’en never gave up their Rights and Title to the territory in a landmark case called Delgamuukw-Gisdaywa.

Unlike previous RCMP raids on Wet’suwet’en territory, the enforcing officers were a mix of local police and members of the force’s Community-Industry Response Group, commonly called C-IRG. The C-IRG is a special B.C. unit set up in 2017 to police opposition to industrial projects like Coastal GasLink. In 2019, the B.C. Supreme Court issued an injunction against anyone impeding construction of the pipeline, which set the stage for much of the police enforcement to date.

However, the search and arrests were not an enforcement of the injunction.

The Civilian Review and Complaints Commission, a federal watchdog agency responsible for responding to allegations of police misconduct, recently launched a systemic review of C-IRG, including an examination of whether its actions are in line with standards and expectations of provincial and federal Indigenous Rights legislation. A spokesperson with the RCMP told the CBC the force is working cooperatively with the commission to make sure it has “comprehensive access and a fulsome understanding of the C-IRG’s policies, procedures, practices, guidelines, training and deployments.”

Adam Olsen (SȾHENEP), a Green party representative and member of Tsartlip First Nation (WJOȽEȽP), questioned Mike Farnworth, B.C. Minister of Public Safety, about the RCMP unit in the Legislative Assembly shortly after the arrests were made. In his question, he referenced a recent government decision to allocate an additional $36 million to the task force.

“Right now, this crew is rolling, and the minister knows this, on Indigenous people in their own territories, as we speak,” he said. “The extent of the human rights abuses and violations of Indigenous Peoples on their own lands by this unit has not yet fully come to light. How does this government justify giving a controversial RCMP unit tens of millions of dollars, and will this B.C. NDP government stand this militarized police unit down while they’re under this investigation?”

Farnworth said the police have a job to do.

“It costs money to do that. We have to pay for the costs of the policing that takes place in the course of the enforcement of these injunctions,” Farnworth said.

The RCMP operations were quickly condemned by human rights advocates and Indigenous leaders.

“Under the governance of their Hereditary Chiefs, the Wet’suwet’en are standing in the way of the largest fracking project in Canadian history — today’s raid constitutes a federal response to Indigenous defense of their land against this fracking project,” Grand Chief Stewart Phillip, president of the Union of British Columbia Indian Chiefs, said in a statement.

“The rights of Indigenous Peoples to live free of violence and intimidation in their own homelands must never be subjugated to the interests of fossil fuel companies.”

K̓áwáziɫ Marilyn Slett, elected Chief councillor of the Heiltsuk Tribal Council, noted the United Nations Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples visited Canada in February and met with Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs and land defenders, including Woos’ daughter.

“His preliminary report after the visit raised the exact concerns that we have raised again and again — that the criminalization of Indigenous human rights defenders is rampant and must be stopped,” she said in a statement. “Today’s raid is in contravention of the [United Nations] Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples which both Canada and B.C. have passed legislation to implement, and is a gross display of the ongoing supremacy of the colonial military industrial complex.”

Sleydo’ Molly Wickham, spokesperson for the Gidimt’en camp, said the police actions reflect a long history of injustice to Indigenous Peoples.

“The constant threat of violence and criminalization for merely existing on our own lands must have been what our ancestors felt when Indian agents and RCMP were burning us out of our homes as late as the ‘50s in our area,” she said in a statement.

Gisday’wa frowned when asked how he felt about the police enforcement.

“What they’re doing out here, they’re just doing that to bully the people here, the land protectors — it’s not right. This is our own land.”

All five land defenders were released from custody and told to appear in court in July.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...