Court halts tailings increase as First Nation challenges B.C.’s decision to greenlight it

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

The number of renewable energy projects in Canada’s remote communities has doubled since 2015, which is helping to mitigate diesel use, according to a new report by the Pembina Institute.

The report quantifies how renewable energy systems, as well as energy efficiency programs and electrical grid tie-ins, are helping communities pivot away from fossil fuels for heat and electricity generation.

“What’s needed is a hard look at both sides of the coin, so to speak — where we have come from, but projecting the future and where we need to go,” said Dave Lovekin, Pembina’s director of renewables in remote communities, noting that a litany of government-sponsored programs aimed at transitioning to renewable energy contributed to the reduction.

The research looks at total energy use in communities between 2015 and 2020, though most renewable energy projects came online within the past two years. The report found that while diesel is being displaced by renewables projects and energy-efficient systems, overall consumption of fossil fuels is still increasing due to the growing population.

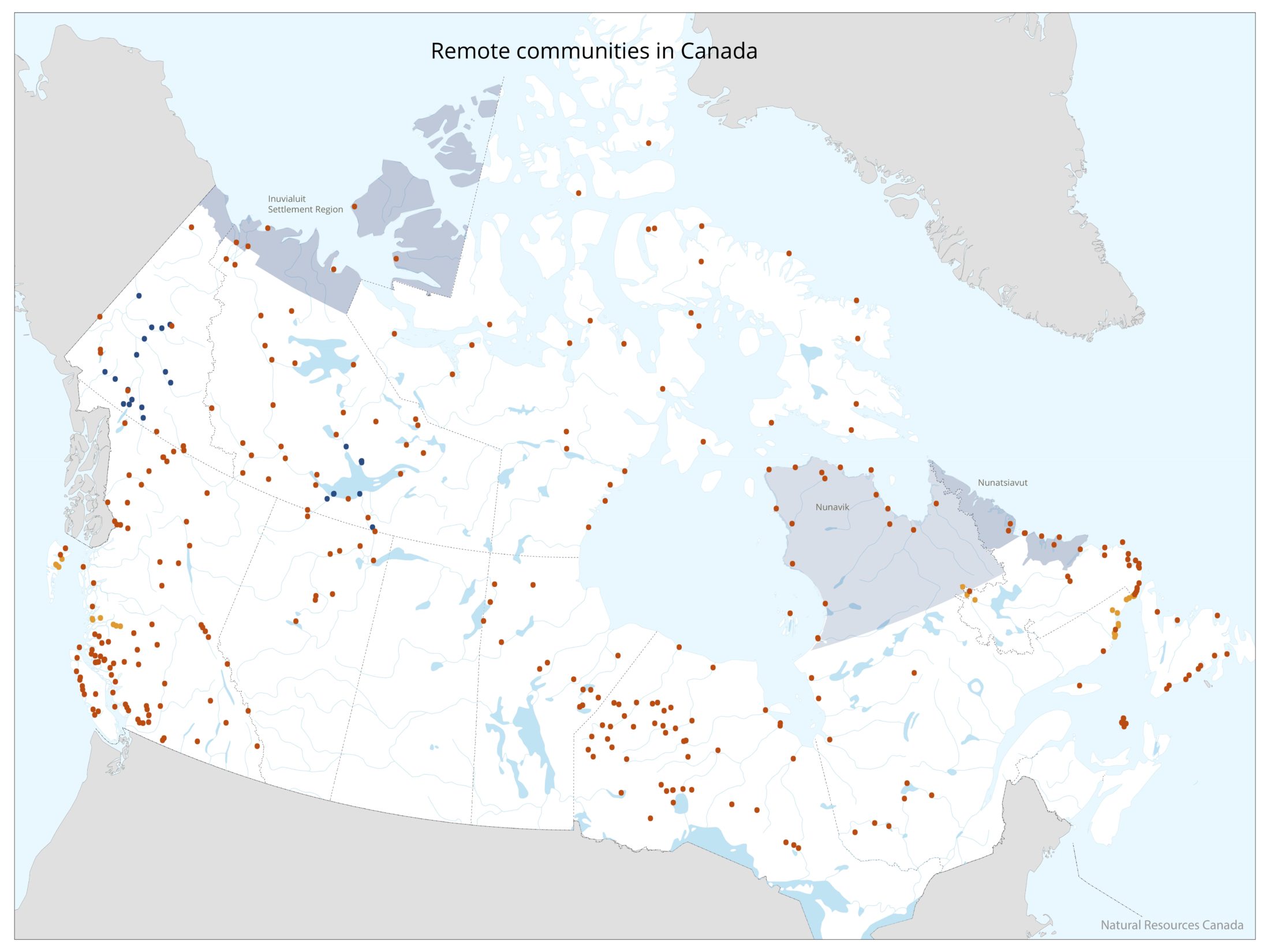

Location of diesel-reliant remote communities. Communities coloured orange use diesel for both electricity and heat; blue use diesel for heat but are connected to electrical grids; yellow use diesel for heat but are tied into small hydroelectric facilities. Map: Pembina Institute

Across Canada, 238 remote communities rely exclusively on diesel for electricity and/or heat. The more remote a community is, the higher the likelihood that diesel is used, Lovekin said, pointing to the North, which has frigid temperatures and many poorly insulated houses.

Nunavut’s electricity, heat and transportation needs, for example, are met with diesel. There have been improvements in the territory in the past five years, but diesel reliance is still pegged at 99 per cent, the report says.

In the lead up to the 2019 federal election, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau flew to Nunavut’s capital city of Iqaluit and made a pledge to eliminate the reliance on diesel for electricity in remote communities by 2030. The Liberal party says investing in “clean, renewable and reliable sources of energy” is the way to do this. The promise ties in to the government’s aspiration to hit net-zero carbon emissions by 2050.

But according to the federal government, as of September of 2019, Canada was off track for its 2030 emissions reduction target by 22 per cent. And the Pembina report notes that the government has not set a goal of eliminating diesel use for heating.

Martha Lenio, an Arctic renewable energy expert for WWF-Canada, said heating must be targeted if a dent is to be made in reducing diesel use. In Nunavut, where Lenio is based, heating accounts for two-thirds of diesel use, she said.

The Pembina report illustrates there is momentum toward meeting the government’s emissions reduction targets across remote communities, but it says more investment is needed.

“We have a long way to go,” Lovekin said.

There’s been an 85 per cent increase in projects that reduce diesel consumption in remote communities since 2015, the report says, whether through energy efficiency or renewables projects. It also notes that the scale of renewables projects is increasing. Solar photovoltaic installations in some areas now generate 500 kilowatts of power — a jump from the average capacity of 10 to 20 kilowatts in earlier projects.

The report captures Old Crow’s solar array — the largest in the circumpolar North. Vuntut Gwitchin Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm recently told The Narwhal that the project would displace 189,000 litres of diesel per year once completed. Over its decades-long life cycle, this would equate to a 1,270-tonne reduction in greenhouse gas emissions, including those that come from flying diesel fuel into the roadless community.

Another project the study looks at is Fort Chipewyan’s solar array, which, once completed this year, will displace 800,000 litres of diesel annually for the Alberta community. In a news release, Pembina said it will be the largest solar project in a remote community.

The report calls the 682 million litres of diesel projected to be used in remote communities in 2020 “staggering.” (Two-thirds is expected to be used for heating purposes, while the other third will be used to create electricity.) In 2015, 655 million litres of diesel was used for heat and electricity, according to the report.

In 2020, 79 per cent of electricity in remote communities is projected to come from diesel, the report says, noting that Nunavut and Nunavik, in northern Quebec, rely most heavily on the fuel; 19 per cent will come from renewables; two per cent from other fossil fuels.

In Iqaluit and remote communities across Canada, fuel tanks are fixed to houses for heating oil. Photo: Elaine Anselmi

Diesel fuel is projected to provide 69 per cent of heating this year in remote communities, with renewable options — wood stoves and biomass — providing 21 per cent. The remaining 10 per cent is expected to come from other fossil fuels.

There are human and environmental concerns attached to diesel use. Particulate matter from burning diesel can get into the air, impacting human health, Lovekin said. The biggest concern he’s heard from communities, though, is that spills could happen either in situ or when diesel is being transported.

“The environmental harm to bodies of water, land, aquatic life is substantial,” he said. “It takes a lot of money to clean.”

The buck doesn’t stop at government coffers. Private investors and banks can also play a role in getting communities off diesel by offering zero-interest or guaranteed loans for energy projects, Lovekin said.

“Indigenous communities are very much hamstrung by government grants and the cycles and processes of those grants,” he said, noting that roughly 70 per cent of communities included in the report are Indigenous. “We’ve got to change the economics of these projects.”

“We have to continue to listen to communities and community leaders in what they want in their clean energy transition and if those communities want to drastically reduce their diesel [use].”

Lenio is hopeful, seeing the movement toward clean energy gain speed across the North.

“This report contributes by collecting that data needed to make some meaningful projects that make sense for communities,” she said. “A lot of the groundwork has been laid. I think in a few years, you’re going to see larger projects starting to bring down diesel use in the remote communities.”

Update July 10, 2020 9:25 a.m. PST: This article was updated to correct the number of communities included in the study. The article originally stated 451 communities were involved, but that figure represents how many times electricity use and heat use were accounted for among all communities — however many use diesel fuel for both heat and electricity. In total, 238 communities were included in this study.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...