In a Nova Scotia research lab, the last hope for an ancient fish species

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

Updated on June 21, 2022, at 4:58 p.m. ET: On June 17, the 21 nations of the Robinson Huron Treaty announced a proposed $10-billion settlement. The payment would come from the federal and provincial governments, both of which must approve the settlement before it can be finalized.

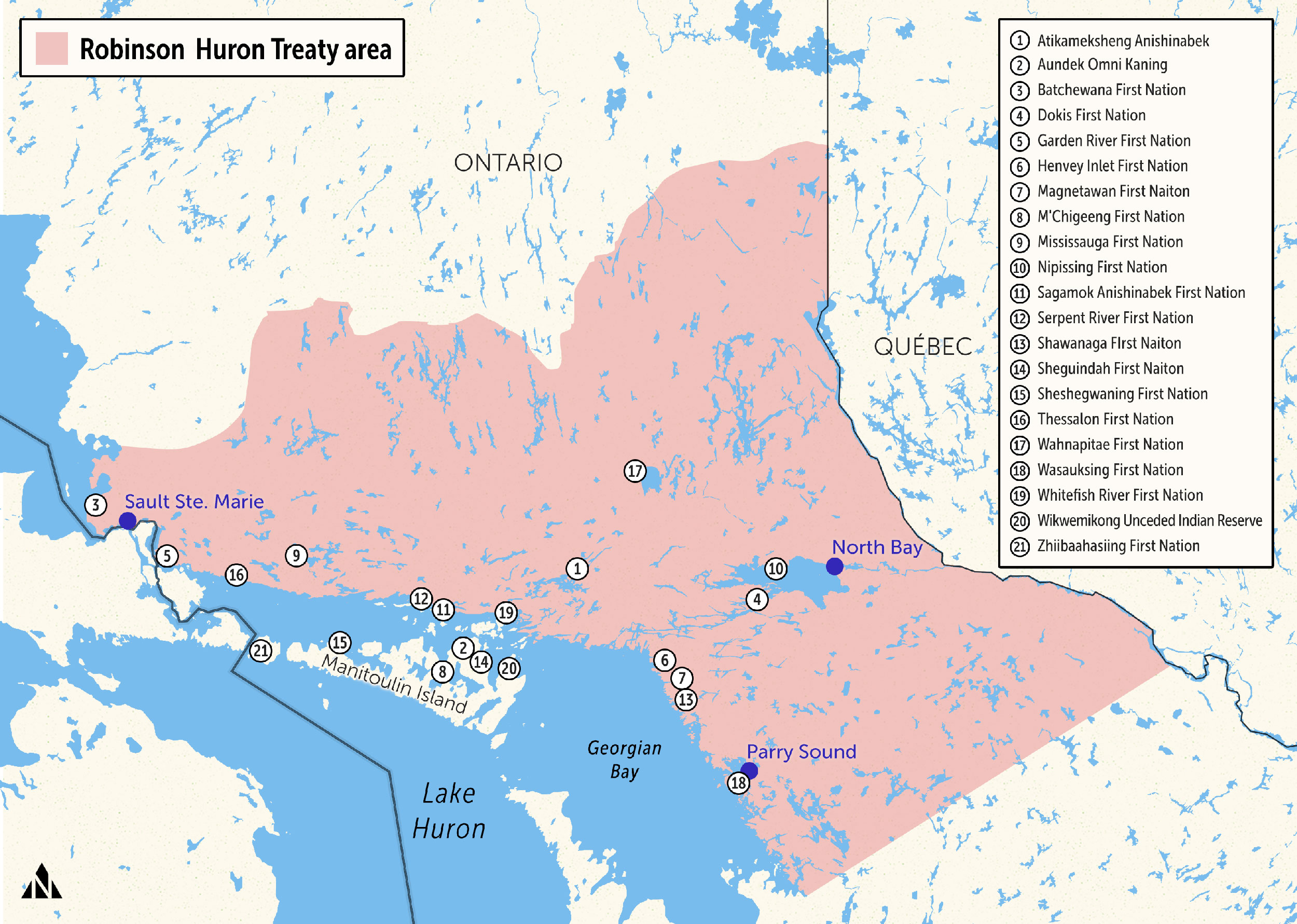

In northeastern Ontario, a treaty dispute over 170 years in the making might finally be coming to a close. A legal trust known as the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation Fund is seeking unpaid treaty annuities — annual payments to individual members of the 21 First Nations involved — in a case that could set legal precedents across the country by formally recognizing Indigenous interpretations of historic treaties.

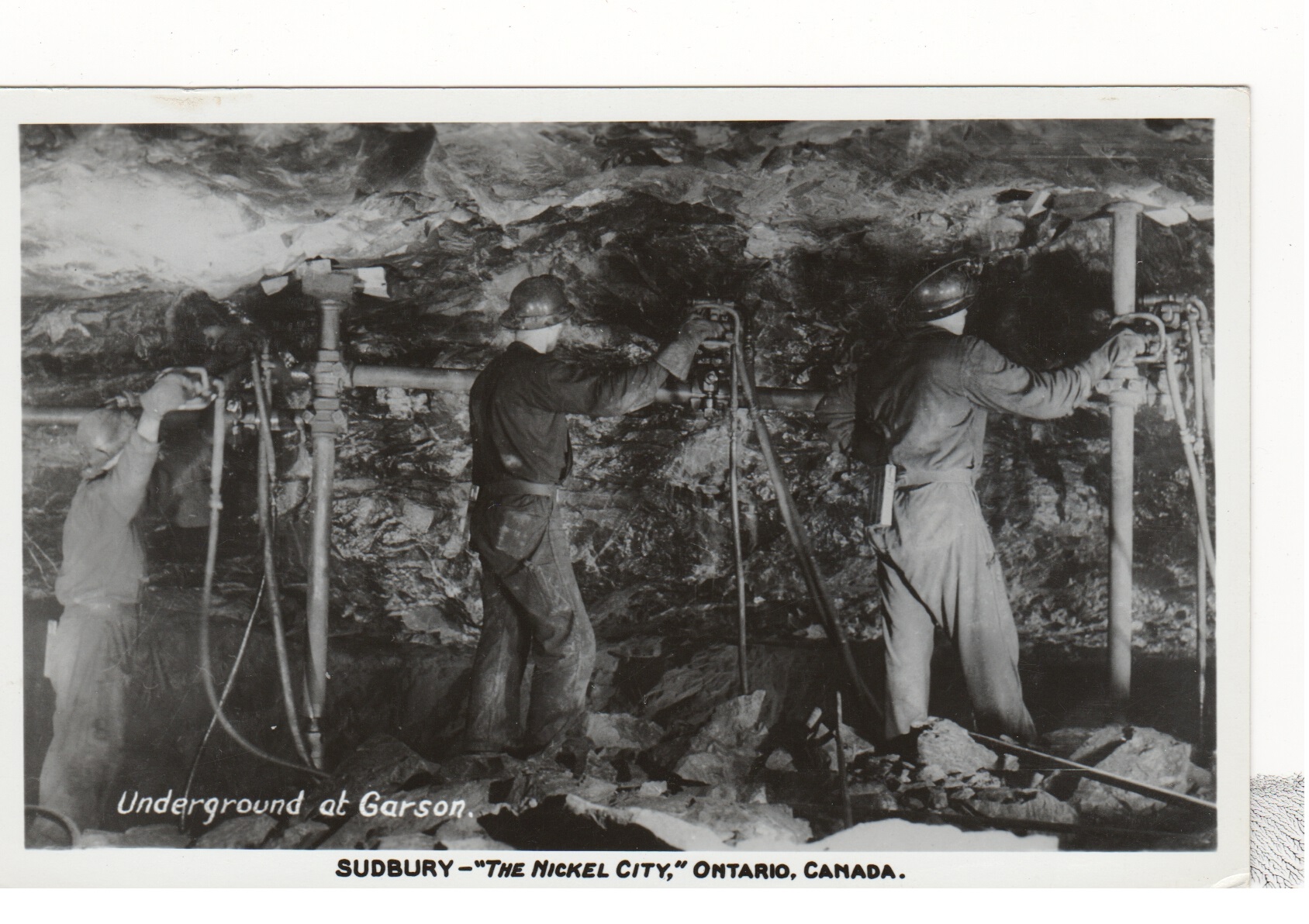

Since the treaty’s signing, the region has produced one of the largest nickel mining operations in the world, alongside historic copper, uranium, lumber and fishing industries. Yet the annuity has remained the same since 1875 — at only four dollars per person — despite a unique clause in the treaty that ties the value of the annuity to the expansion of resource development in the region.

“We were supposed to have a true sharing relationship over the land that was ingrained right at the onset [of the treaty],” Chief Dean Sayers of Batchewana First Nation, one of the Robinson Huron communities, says. “Of course, it didn’t go that way. But now we’re in a position where we expect to see a true reflection of that original understanding.”

Hailing from Parry Sound to Sudbury, and North Bay to Sault Ste. Marie along the shores of Lake Huron, the 21 First Nations in the trust are seeking to enforce the terms of their treaty with both the federal and provincial governments.

Governments neglected the treaty for more than a century. Now, after more than a decade of preparation and litigation, the Robinson Huron communities are on the precipice of realizing the vision of their ancestral leadership to seek reciprocal compensation for resource extraction — and secure their nations’ existence for future generations.

By the 1840s, Canada, then a British colony, was granting mining patents in the area of Sault Ste. Marie in northern Ontario. But the land was not yet the government’s to grant. The Crown had never made any treaty with the local Anishinabek to obtain any rights to their land. Chiefs Shingwaukonse, Nebenaigoching and other Indigenous leaders met with then-governor general Lord Elgin in 1849 in Montreal demanding a treaty and reminding the Crown of their past alliance in the War of 1812.

But miners continued to flood the region, leading to further conflict that would escalate in November 1849, when Indigenous leaders evicted a mine camp at Mica Bay. Their demands were finally heard, though not before Shingwaukonse and others were arrested. The charges were eventually dropped and the treaty was signed a year later alongside the Robinson Superior Treaty — each treaty is named for the Great Lake region which it encompasses — with Crown negotiator William Robinson in September of 1850.

Essential to both treaties was the inclusion of an augmentation clause — a unique note in both treaties that said annual payments would increase if resource extraction revenues grew. The Robinson Huron Treaty says the Crown promises if “the territory … shall at any future period produce an amount which will enable the government of this province, without incurring loss, to increase the annuity hereby secured to them … shall be augmented from time to time.”

In plain language, according to Sayers, his people said “We’re going to share with you that copper, we’re going to share with you that gold, that silver, those minerals,” provided the Crown shares back. “It is a sharing relationship of our inheritance. And we expect that to be honoured as part of the promises that were made that treaty time.”

Since the treaty’s signing, the region has witnessed well over a century of commercial resource extraction: nickel in Sudbury, copper in Bruce Mines, fishing on Manitoulin Island, uranium in Elliot Lake and more. Since operations began in Sudbury, its more than 77 mines generated $330 billion in revenue, based on contemporary mineral prices. But the annuity was only raised once, in 1875, from $1.70 to four dollars per person, which members can still receive each year. In 2020, then-chief Duke Peltier of Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory told TVO: “As hard as it can be to line up for that four-dollar payment on an annual basis, it’s a grim reminder to the Crown that the terms are not honourable.” Now, his nation and the other signatories could possibly receive billions in back-owed payments.

The passing of the Indian Act of 1876 took precedence over treaty arrangements, giving huge control over Indigenous communities to the federal government and its Indian agents across the country. In the century-plus since, Robinson-Huron chiefs made numerous attempts to address the matter with both Canada and Ontario, since provinces handle resource extraction. The recognition of Treaty Rights weren’t formally codified until First Nations fought for their inclusion in the Constitution Act of 1982, and it would take decades of court decisions to put the Robinson-Huron communities on a solid legal footing to press forward with their case.

In 2010, the Robinson Huron Litigation Trust was created, representing 21 First Nations that are treaty beneficiaries. The case saw its first day in court in September 2017, after all parties submitted over 30,000 pages of evidence, which “may well be the most comprehensive collection of historic and cultural material ever amassed on the making of the Robinson Treaties and the life and history of the Anishinaabe,” Ontario Superior Court Justice Patricia Hennessy wrote at the time.

For Sayers, the process has been a long time coming. “The evolution of different governments, society, legal decisions on the Canadian side, the evolution of Indigenous Rights being more recognized in the last 20 to 30 years — it’s all coming to a climax right now,” Sayers says. “It’s an incredible feeling to be a part of this and to continue with the implementation of the original spirit and intent of our relationship.”

The case, Restoule v. Canada, is named for trust chair and plaintiff Mike Restoule. The trial was split into three stages: first to interpret the meaning of the augmentation clause, second to determine whether the treaty is subject to the statute of limitations and last to determine the compensation owed to the Robinson Huron Anishinabek.

In 2018, the Ontario Superior Court upheld the Anishinaabe interpretation of the treaty — that its intent was to share the land and Crown revenues from it in a mutually beneficial manner and that the mechanism to share that wealth was the annuity, which was supposed to increase with growing resource development. “The best possible interpretation of the parties’ common intention … is that the Crown promised to increase the collective annuities, without limit,” Justice Hennessy wrote.

In the second phase, which wrapped up in 2020, the Ontario government argued pursuing the back-owed annuity was subject to a statute of limitations and that payment was the responsibility of the federal government. Hennessy disagreed: “Treaties are part of the constitutional fabric of this country. Simple contracts they are not.” Ontario appealed stages one and two and, after the Ontario Court of Appeals largely upheld Hennessy’s decisions, filed an appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada in 2022, which is set to be heard this fall.

Despite the pending Supreme Court hearing, the third stage concerning compensation was set to begin in January of 2023. It has since been paused for ongoing out-of-court negotiations.

While the Robinson Huron negotiations aren’t public, a parallel case is being brought to court by members of the Robinson Superior Treaty, which contains the same augmentation clause. In that case, according to the National Post, the province cites a report commissioned by the Crown to estimate the value of lost annuities, arguing that Robinson Huron signatories are owed $2.7 billion, while Robinson Superior signatories are owed $35 million. The province maintains the costs of infrastructure — for things like mining research, forest management and “colonization roads and railways, which of course the harvested resources could not be moved to market without,” as the Crown argued in court — outgrew any revenues.

The First Nations in that case called an expert witness, Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, to assess the financial losses incurred by their communities. In early February, Stiglitz expressed skepticism at the Crown’s argument, saying if money was an issue, another solution was obvious. “Seeing all the losses, what would a reasonable actor do? Rather than having these lawsuits, [they would say]: ‘take the land back. We’ll save ourselves a lot of money by paying you to take the land,’ ” he says. “That doesn’t comport.”

Factoring in compound interest that would have been earned had Indigenous recipients been able to invest their collective annuities, Stiglitz pegged resource extraction revenues in the region at $126 billion, of which the First Nations are owed 84 per cent — or over $100 billion. He acknowledged the “sticker shock” of such a figure, but said “compounding the significant deficiencies over 170 years is going to inevitably wind up with big numbers.”

Since the Robinson Huron negotiations are private, Sayers could not speak to the specific terms of the settlement process. However, he says negotiations have continued even after the mediator, former senator Murray Sinclair, stepped away for health reasons. “We’re in a good place with the discussions. We’ve had ceremony and from our ancestral perspective, we are at the right place. We do have to work through issues with representatives of Canada and Ontario, and we are doing that.”

While the augmentation clause is unique to the Robinson Treaties, legal experts say the case has wide-ranging implications for how courts could handle future treaty disputes across Canada. Hennessy’s stage-one decision dedicated over 3,000 words to outlining the local Anishinabek worldview: their spiritual beliefs, political and legal structures, using the expert testimony of local Indigenous historians and Elders to understand the intent of Shingwaukonse and others who signed the treaty.

“We have not just some words from the court about listening to the Indigenous perspective on the dispute,” Michael Coyle, a law professor at Western University in London, Ont., says. “We have, enshrined in the court’s ruling, an equal recognition of the Indigenous perspective on what the treaty was intended to achieve.”

Kate Gunn, a partner at First Peoples’ Law, a law firm dedicated to the rights of Indigenous Peoples, notes that Hennessy’s recognition of the treaty’s underlying intent “does open the door for other groups to be on a stronger footing,” when asserting their own historic treaty interpretations. Discrepancies between the text of a treaty and the Indigenous understanding of the treaty aren’t uncommon.

“For so many Indigenous parties, regardless of what the written [treaty] text says, their position has always been that they didn’t give up all the rights to their lands and resources. Seeing how that’s addressed as part of this has been really significant for us.”

Both Coyle and Gunn say the real precedential impacts will come at the Supreme Court level. “Rulings in Restoule may well set an example for the amount of respect and attention that should be given to Indigenous understandings of what was at stake and what was agreed in historic treaty negotiations,” Coyle says. Even if they settle before the Supreme Court hearing, “it would still be a significant precedent, being a decision from an influential and respected court of appeal in this country,” Coyle says.

Sayers has been involved in the litigation since the trust was founded in 2010. The historical and spiritual significance of restoring the treaty relationship is not lost on him. One of his ancestors, Chief Nebenaigoching of Batchewana, signed the treaty himself. “Everything is aligning,” Sayers says. “The essence, the medicine of that [negotiation] table is incredible. Everybody sitting there, I believe, has an understanding that we are at a really incredible time in history right now.”

The settlement will create economic opportunities and help improve community infrastructure and services, but “it’s so much bigger than the monetary component,” Sayers says. It’s about survival. “We know that we’re going to still have Ojibwe, Potawatomi, Odawa nations continue to flourish with language, culture into the future. We have an incredible tool with the implementation of this treaty so that we can see this unique worldview continue,” he says.

“It is part of the secret to looking after North America: our water systems, our forest systems, our land systems,” he adds. “I do see the sun rising, and I can see a beautiful day coming for everybody on our lands here in Canada.”

Updated April 13, 2023, at 5 p.m. ET: This article was updated to clarify that some First Nations in the map area are not signatories to the Robinson Huron Treaty.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Racing against time, dwindling habitat and warming waters, scientists are trying to give this little-known...

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...