Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

Editor’s note: Karsten Heuer passed away on Nov. 5 surrounded by family in Canmore, Alta.

This story has been co-published with The Globe and Mail.

In October 2021, Karsten Heuer found himself sprawled on the ground, helpless, at the bottom of an aspen tree.

He had been searching for elk in Alberta’s Bow Valley, perched in a hunting stand nearly eight metres off the ground. Then he fell. He doesn’t know how. He was unconscious, lying on the ground for more than an hour before rescuers arrived.

His back was broken in several places, ribs too; his sternum was cracked and he was struggling to breathe with collapsed lungs.

He was alone in the mountains he loves.

“I wasn’t in pain,” he remembers, sitting in his backyard in Canmore on a June afternoon, sun streaking one side of his still-youthful face. “I was actually okay with it. It was October, the sun was on my back, I could hear trumpeter swans on the lake calling, and other bird songs, and I was like, ‘Wow, this is actually a pretty nice place to die.’ ”

It’s the kind of thought that might only occur to someone who has lived like Heuer. He has traversed thousands of kilometres through the Rockies on foot and followed a caribou herd for months through the north of the continent. As a conservationist, he worked to protect wildlife corridors in Banff long before they were well known. He led the team that brought bison back to Banff National Park for the first time in 140 years. He was executive director of the non-profit conservation group Yellowstone to Yukon Initiative for a time. He is a perpetual thorn in the side of a local developer that wants to dramatically expand Canmore. And he has written three books and is working on a fourth.

He was one of the early advocates of what is now known as large-landscape-scale conservation. This model takes into account the huge scope of some animals’ terrain, a departure from caring for the land in a patchwork of small protected areas.

In conversation, Heuer, 55, flips easily between the large and the small — the 4,800-kilometre-long stretch of mountains he considers home, and the comparatively modest town of Canmore, whose population could be doubled if the development he’s fighting is green-lit. He also moves between straight autobiographical facts to experiences that touch on the spiritual.

He fits the smallest pieces into the larger whole, his philosophy the result of a collection of experiences that few could match over the course of a long life.

But Heuer’s life won’t be long. He expects to be dead by the fall.

Two years after surviving that fall from his tree stand, he noticed changes — he couldn’t drink a single beer without acting drunk, for one — and was diagnosed with a fast-acting and fatal neurological condition called multiple system atrophy.

Heuer says he isn’t willing to wait around for the worst of it. He has scheduled an assisted death for the fall, leaving on his own terms.

It’s not known if the neurological condition was triggered by his accident in the woods, but lying there in the aftermath of the fall shifted Heuer’s relationship to his own mortality. When he finally received his diagnosis, there was an earned wisdom that gave him a measure of peace.

“I was really close to the precipice already, staring at it,” he says. “And I was like, ‘This is okay.’ ”

Heuer has long made his home in the Rocky Mountains. The famed range conjures images of untrammelled national parks and snow-covered peaks, but the ecosystem is under threat.

In the 1990s, research emerged showing the impacts of roads crisscrossing the landscape. Expansive ecosystems were being cut into smaller and smaller fragments.

Not only that: clearcuts are common in this wilderness. Pipelines carry crude oil across the continental divide. Coal mines have taken apart mountains. Charming towns have exploded in popularity, sending development deeper and deeper into the woods. The climate is changing. A natural wildfire cycle has been suppressed and blazes are burning bigger and hotter.

In some ways, the situation is now more dire, but over the decades, Heuer and others like him had been fighting for better outcomes, and winning victories along the way.

He entered the conservation scene in the early 1990s, when he was in his 20s. It was a time when few acknowledged the importance of preserving landscapes for reasons other than tourism. Canada’s national parks had long prioritized the enjoyment of visitors.

Then came Pluie — a female wolf collared by a researcher in 1991. As a result of the tracking device, researchers were able to conclude that she wandered more than 100,000 square kilometres across Alberta, B.C., Montana, Idaho and Washington, travelling far greater distances than previously documented. Wildlife had been traversing these expanses for millennia. Indigenous people had known, of course, but now the understanding was widespread. The idea helped to spur the modern landscape-level conservation movement.

Heuer was familiar with those landscapes. He grew up in Calgary and travelled to the mountains almost every weekend with his German-born parents to hike, camp, cross-country ski and fish. Heuer has never been far from wild places. He always knew he wanted to work outside.

“Our son’s 19 right now. I was a little bit like him — not knowing what I wanted to do.” For a time, he thought he would be a wildlife veterinarian. That didn’t work out. “It turned out I was allergic to everything with hair and four legs,” he says.

It was a setback, but as Heuer recounts the pivotal moments of his life, it’s striking how he seemed to have been in the right place at the right time. He has good timing, which he says is “a pretty funny thing to say to a guy who’s going to die prematurely.”

Or perhaps he just knows when to seize a moment.

In 1991, while he was studying ecology at the University of Calgary, Heuer volunteered for a study to recolonize the Rockies with wolves. One day, as he was chatting with the biologist in charge of the study, someone came into the office with a bruise on his face in what Heuer describes as the exact shape of a hoof.

“He and I got talking,” he says. “Turns out he was kicked by an elk.”

Some would take it as a warning, but Heuer was intrigued.

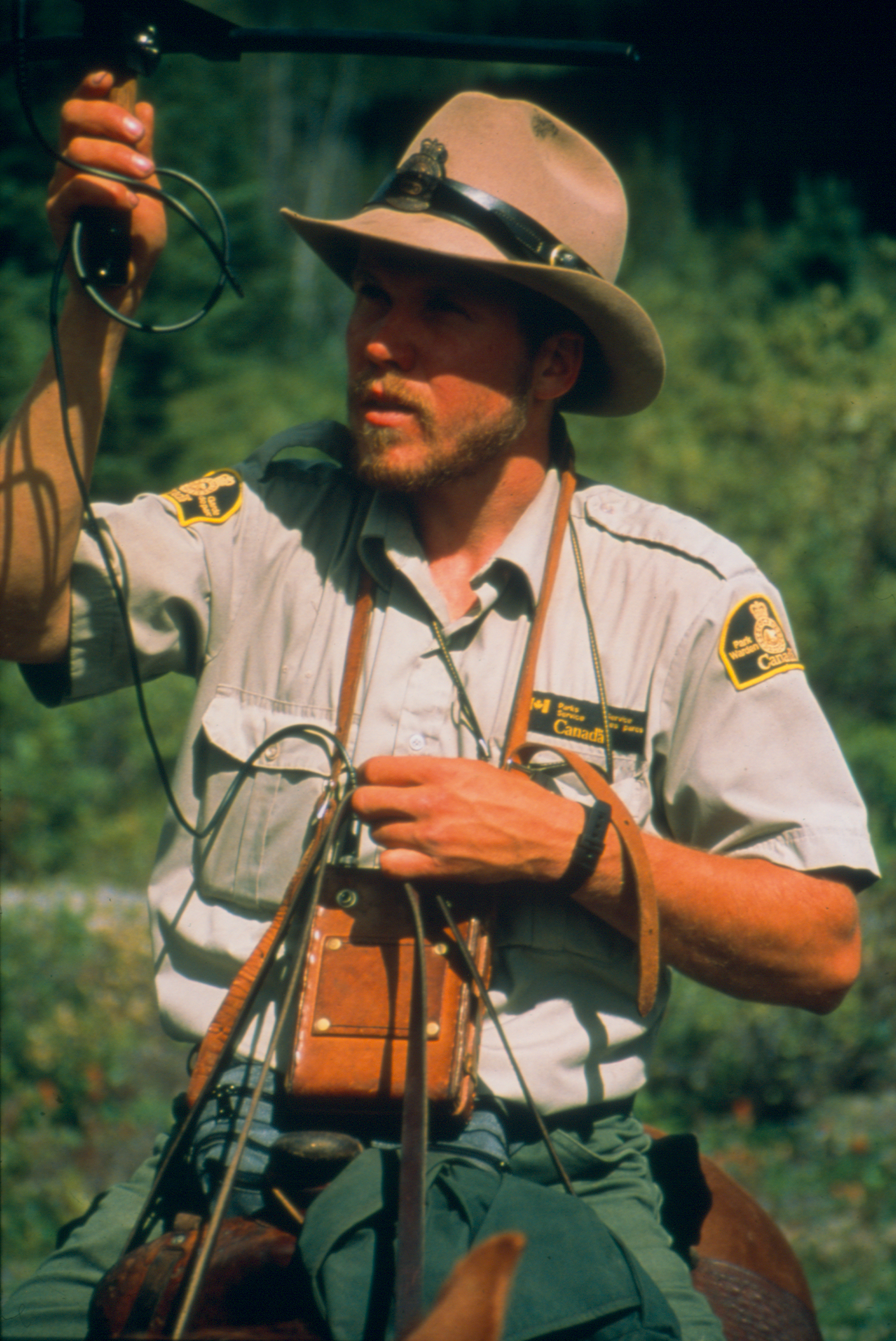

The man was a Parks Canada warden. It was after that conversation that Heuer started working for the agency, first as a student and then as a warden. It was the perfect job to anchor Heuer — he was able to take leaves to pursue other passions — and he worked in various roles for decades, culminating in leading a program to reintroduce bison to the park.

Early settlers to North America hunted Plains bison aggressively, culminating in the animal’s near-extinction in the late 1800s. The animals had been absent from the Banff National Park ecosystem for more than a century when Heuer led an effort to release bison in the mountains again, starting with 31 of them in 2018.

Harvey Locke, a renowned conservationist in his own right, calls that project a “wild success.”

“We’ve restored a missing species to Banff that’s been gone for 140 years,” he says. “It’s not gone anymore and it’s fantastic. It’s a really tangible thing.”

The bison are deep in the backcountry and Heuer and his colleagues travelled by horseback to check on them.

It is just one of the many things he’s had to say goodbye to.

“It was kind of hard putting all the horse stuff away in the locker for the last time,” Heuer says. “One of the gifts of this is … there are a lot of lasts and you can take a moment to honour those feelings.”

One early experience in his career showed Heuer what his job could be at its best. In 1992, he was contracted to help conduct a study into wildlife corridors in developed areas in Banff.

It was life altering.

That winter, the team trekked through the snow on foot, following wildlife such as wolves, lynxes and cougars to map the animals’ travel patterns.

When they presented their findings to town council, the response was immediate. A neighbourhood expansion was stopped and soon the park moved other developments — the old bison paddock, airport and cadet camp — out of wildlife travel routes, too. Wolf use in that reclaimed area jumped 700 per cent, according to Heuer.

“The moral of the story was — I saw it at a pretty young age, basically fresh out of university — that if I apply my knowledge in the field, you actually could make a difference.”

It’s part of why he continues to fight. In 2021, he helped revive Bow Valley Engage, an organization that advocates for what it calls “responsible development” of the town of Canmore. Much of its work has pushed back against Canmore’s proposed development, Three Sisters Mountain Village.

Heuer sees the expansion as a clear threat to the travel corridors used by wildlife, with implications both at the local level and also for the larger Rocky Mountains ecosystem. He will fight as long as he can, even if he may not see the final result of his work

Heuer’s understanding of the Rockies as a vast, connected ecosystem started to crystalize when he first met conservationist Harvey Locke in the early ’90s. Heuer watched a presentation Locke gave about the need to consider the Rocky Mountains one contiguous stretch of habitat that needed protection — an idea spurred by wildlife like Pluie the wolf. Heuer was captivated.

After that talk, Heuer attended an early meeting of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, Locke remembers. “And he said, ‘Gee, I’d like to walk from Yellowstone to Yukon, on my own money. Is it okay if I do it kind of in association with what you’re trying to do?’ ”

Locke was struck by Heuer’s determination. “I said, ‘You bet. You bet you can.’ ”

“I see Karsten as a guy who does what he thinks is important no matter what the effort required is,” Locke says. “And I think that’s as good a one-sentence summary of Karsten as you can come up with.”

Heuer embarked on his 3,400-kilometre journey from Yellowstone National Park, Wyoming, to Watson Lake, Yukon, in 1998.

During that months-long trek — there were 188 days of actual walking — Heuer’s life and outlook changed. He saw first-hand how interconnected the land was, understanding not just how the land was used, but how intact it still was.

Traversing it footstep by footstep, from valley to valley, he started to understand the grand sweep of it all at a human level.

“By the end, the Rockies really felt like my home: not just Canmore, not just the Bow Valley,” he says.

The journey attracted plenty of media attention, with stops along the way used to promote the Yellowstone-to-Yukon idea at a time when local papers and television news were critical to people’s information ecosystem. He did hundreds of interviews, talked to rooms full of people with differing viewpoints, experienced corporate pushback, confronted conspiracy theories about United Nations land seizures and even received death threats.

“It was a good training ground for finding commonalities in disparate audiences and building off those commonalities,” Heuer says. “Not in a compromising way — in a productive way.”

He took those skills and used them as a warden and biologist, but also as an activist. He took the helm of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative in 2015, but flying around fundraising and socializing sapped his energy and kept him from the wild places he loved.

He took a leave to recover from burnout and never returned.

That didn’t stop his passion for working to protect large swaths of the Rockies. He just found ways to do it without the “strategic planning and all that bullshit” that he said wore him down.

It’s difficult to quantify the impact Heuer’s efforts had on large-landscape-scale conservation, but recent research has found the total protected area from the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem to the Yukon grew by 45 per cent between 1993 and 2018 and at the same time the population of grizzly bears doubled.

Heuer says the Yellowstone to Yukon vision changed how we look at the natural world, and that it helped to leverage small issues into ones that are continental in scale — thinking about how 100 acres on one parcel of land could impact tens of thousands of acres across a region.

Heuer’s trek wasn’t just a catalyst for a lifetime of conservation advocacy — it was also the proving grounds for a great love story.

Leanne Allison and Heuer first met in an arts-focused downtown Calgary school where Allison’s mom played piano. Heuer would spend afternoons at her family’s home while Heuer’s mom pursued her own studies. When Allison, an award-winning filmmaker, joined Heuer for the last half of the hike, it cemented the connection that had been sparked decades earlier.

“We kind of joke that we were boyfriend and girlfriend in kindergarten,” Allison says by phone one day in June. “Then we met again in university. Karsten was teaching canoeing down at the Calgary Canoe Club and his boss was a good friend of mine. She said, ‘Man, you gotta meet this guy. He’s like the male version of you.’ ”

She took up the offer and joined Heuer to paddle on the Glenmore Reservoir. She immediately realized he was the boy etched in her memory from years prior.

“We recognized each other and we became fast friends,” she says.

The two bonded over a shared love of the outdoors and eventually found themselves romantically entwined. Sort of.

“I think we were 21 when we went up and paddled the Nahanni River together,” Allison recalls. “In the Kraus hot springs we had our first kiss under the Northern Lights. Totally romantic. But then we got back to Calgary from that trip and he dumped me.”

It’s not, Heuer says, a moment he’s proud of.

They remained friends — Allison says it would have been impossible not to — and then came the Yellowstone to Yukon trek. She credits that trip in 1998, and Heuer’s view of the world around them, with changing her own outlook, from the idea of mountains as playground, to the mountains as an ecosystem worth fighting for.

“We were together from then on,” she says.

They married and raised a child, Zev, who they introduced to adventures when he was just two, taking the long way around — about 5,000 kilometers by canoe — for a visit with famed Canadian author Farley Mowat.

Zev has taken up some of his parents’ passions. Four years ago, he decided to canoe to his new summer job, more than 1,000 kilometres away in Saskatchewan.

Both Heuer and Allison save their most reverential tone for one of their other great adventures — following the porcupine caribou herd for months across 1,500 kilometres of tundra in Alaska and the Yukon for a film and book entitled Being Caribou. The duo wanted to draw attention to threats to the herd from drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska as the U.S. government pushed to open the calving grounds to oil and gas exploration.

The calving grounds, which were excluded from full protection when the refuge was created in 1980, weren’t opened up then, but the fight has continued. In 2017, the Donald Trump administration opened the area to drilling, but a moratorium was put in place by President Joe Biden and existing leases were officially cancelled last year.

The project involved months of hiking and camping with no planned routes, following wildlife paths in some of the most remote places on earth. There was no agenda but that set by the herd. The experience would cause a profound existential shift in Heuer and Allison.

“As time went on, we started to rely on these different ways of being as we shed the clutter in our own minds,” Heuer says. “We actually became more attuned to signals that the caribou themselves were following, or the signals the caribou are giving each other to coordinate their movements.”

When Heuer returned home and started to write his book, he struggled. He was trying to write about something scientific but it felt more like recounting a dream.

“We came back to the Bow Valley and we looked a little lighter, but generally the same,” he says. “We were treated the same, because we looked the same, but we were fundamentally different. And we kind of didn’t ever feel like we truly belonged.”

But he did belong with Allison.

“I feel so privileged to have shared that with Leanne,” Heuer says. “Imagine you come back and now you’re trying to communicate to your partner in life how you’ve changed. What you experienced. We didn’t have to do that.”

He says that experience left him with a different understanding of his work and its purpose. When he fights to protect wildlife corridors, it’s not just the science behind how wide a corridor should be, or the need to balance X with Y.

“It’s much more than a scientific, logical thing. It has become a spiritual thing where cutting off the corridors, to me, it literally is killing animals knowingly,” Heuer says.

“You couldn’t argue that in front of a judge or at a public hearing or something, but it’s something that I feel in my heart, having known these caribou, the intricacies with how they communicate, the kinds of things that got revealed to us when we just had the time to truly listen and shed our human agendas.”

Allison says the experience has informed all of her work as a filmmaker and environmentalist since, viewing stories through the lens of the animals and spaces she documents. But it changed more than that.

She says it’s “totally cheesy,” but she’ll never forget, near the end of the caribou trek, seeing swans paired up and flying south together as a unit and feeling like she and Heuer were on that same level.

“We were just so in sync and moving across the landscape together was just …” Allison says, trailing off as she fights back emotion. “Yeah, it’s hard. This is kind of hard.”

Across from a small reading chair in the modest mountain home that Heuer and Allison share, a large window frames a view of mountain peaks that climb steeply from this corner of the Bow Valley in central Canmore.

An immensity looms. The bulk of the mountain, the heaviness of what’s to come for Heuer, Allison, their son and their close friends and colleagues.

Bow Valley Engage continues to fight against the massive Three Sisters development. Heuer and his collaborators are awaiting a judicial ruling on an Alberta government decision to skip an updated environmental impact assessment (the original was conducted 32 years ago, long before the current iteration of the proposal). Heuer says the valley and the proposal have changed significantly over those decades.

It is just one of the foundations Heuer has laid for those he will leave behind. He says he has struggled throughout his life to pass tasks on to others, but he’s learning to let that go and make peace with the fact he won’t know how things end.

“Again, that’s another gift,” he says. He lets people help him more now than he ever did before.

Living up to Heuer’s legacy will be challenging. Locke, his friend and early collaborator, says the ease with which Heuer appears to confront any situation comes from a deeply entrenched sense of right and wrong, but that doesn’t mean his life and his work have been easy.

“To live a life where you do what you believe in the whole time is really hard to do,” Locke says. “He has done that.”

Heuer isn’t going on any more long treks, at least not on foot. But he still travels to wild places in his mind, sitting in meditation and walking the peaks and valleys of the mountains he loves. At the same time, he is working on his last book, tentatively entitled Buffalo Lessons: Teachings from the Banff Herd. It will be short — and published posthumously.

He is facing his final journey the same way he has faced all his challenges, both determined and grateful for those gifts it offers — saying goodbye, appreciating what he has experienced.

He is making the most of the months before his death, knowing, as he puts it, he has always favoured quality over quantity.

Allison says the two recently paddled out to the tree where Heuer had his accident, a place she hadn’t visited.

There was a tiny red hummingbird waiting for them, perched on a branch, and morel mushrooms were sprouting from the place where Heuer had lain broken. Allison said she expected big emotions from visiting the site, but she was filled with a sort of calm.

“What we were experiencing with the caribou is these huge cycles, and here we are caught up in that very same thing,” she says.

Updated on Nov. 14, 2024, at 10:46 a.m. MT: This story was updated to correct a photo caption that identified Allison peeking out of a tent in -30C as the couple followed the porcupine caribou herd on foot. In fact, Heuer is peeking out of the tent in the photo.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion