Drawing (on) a decade of climate change in the North

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

One-fifth of all the methane produced using conventional oil and gas methods in Saskatchewan is escaping into the atmosphere, according to new scientific research.

The finding, published in August in a peer-reviewed journal, raises fresh questions about the industry’s control of its pollution and the effectiveness of provincial and federal regulatory oversight.

It comes as the federal government’s deadline approaches to finalize a rule meant to get tougher on the industry, following years of scientific studies showing figures have severely underestimated methane pollution from oil and gas production.

Methane, an invisible, odourless greenhouse gas, traps heat in the atmosphere and threatens the health and safety of communities by presenting respiratory and cardiovascular complications as a ground-level pollutant. In 2023, the federal government proposed draft rules to cut methane emissions from oil and gas operations by 75 per cent below 2012 levels by 2030.

Slashing methane is seen as a key strategy to slow global warming, which among other effects is supercharging the destructive and deadly wildfires tearing through Canada, sending plumes of toxic smoke into populated areas and triggering severe public health impacts.

At the same time, the methane emitted during the industry’s production of fossil fuels is only part of the problem. Most carbon pollution is created when those fuels are eventually combusted for energy, meaning oil and gas methane emissions are just one more layer of pollution on top of everything else.

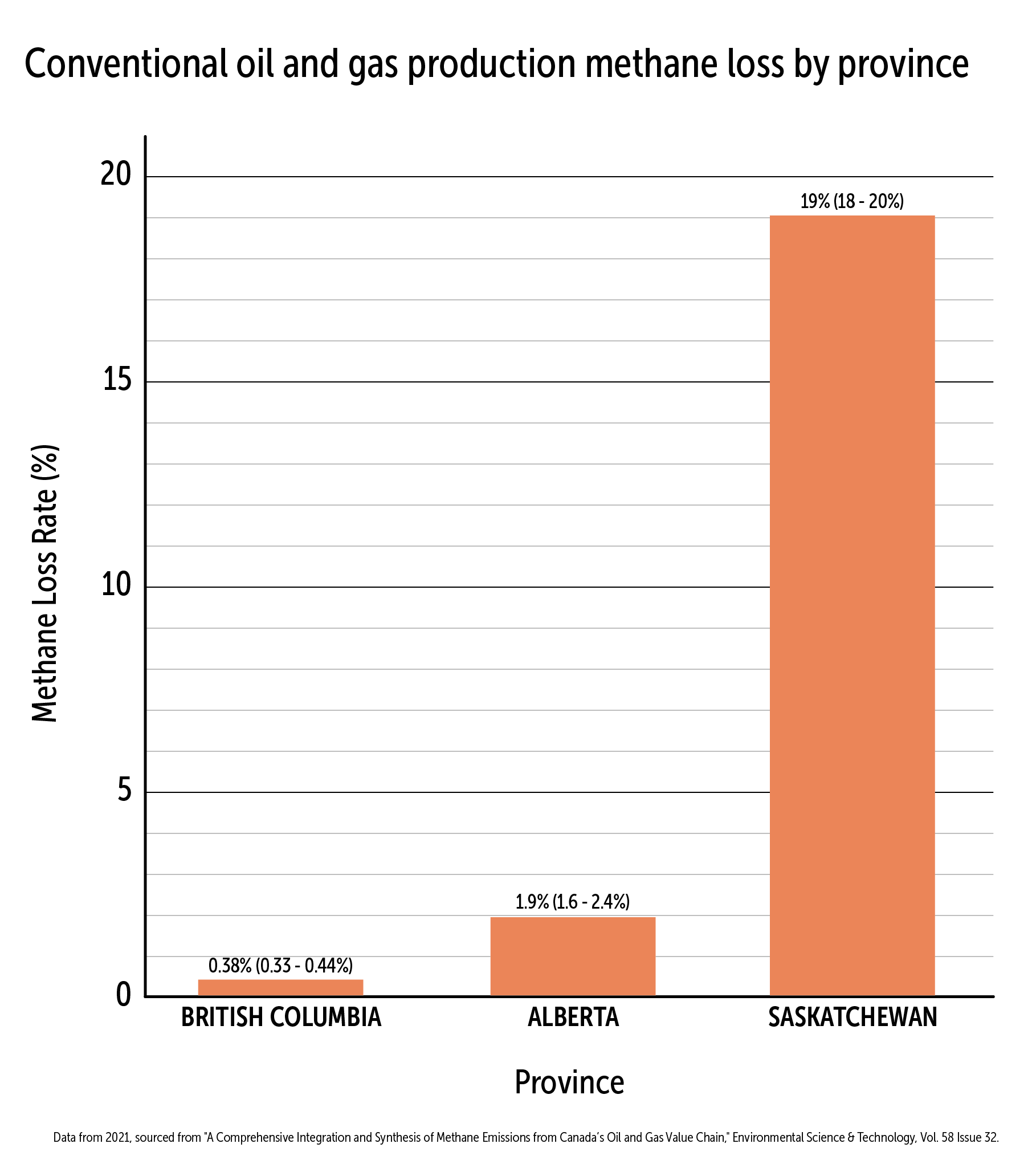

At 19 per cent, Saskatchewan’s conventional oil and gas production had by far the worst methane “loss rate,” or the percentage of the gas that is released into the atmosphere compared to how much is captured, according to the article published in Environmental Science & Technology.

Saskatchewan’s methane loss rate was higher than conventional oil and gas production in Alberta at 1.9 per cent, and conventional oil and gas in British Columbia at 0.4 per cent.

Conventional oil and gas refers to easier to reach deposits that don’t require more specialized methods of drilling like hydraulic fracturing, or fracking. During conventional oil and gas production, methane can leak from equipment like compressors, or it can be deliberately vented from facilities.

“This 19 per cent, to my knowledge, is probably the first time this has shown up in recent papers,” said lead author Katlyn MacKay, a Dartmouth, N.S.-based scientist at Environmental Defense Fund.

“It’s quite high. It shows that there’s a lot of opportunity for improvement, to frame a little silver lining on it.”

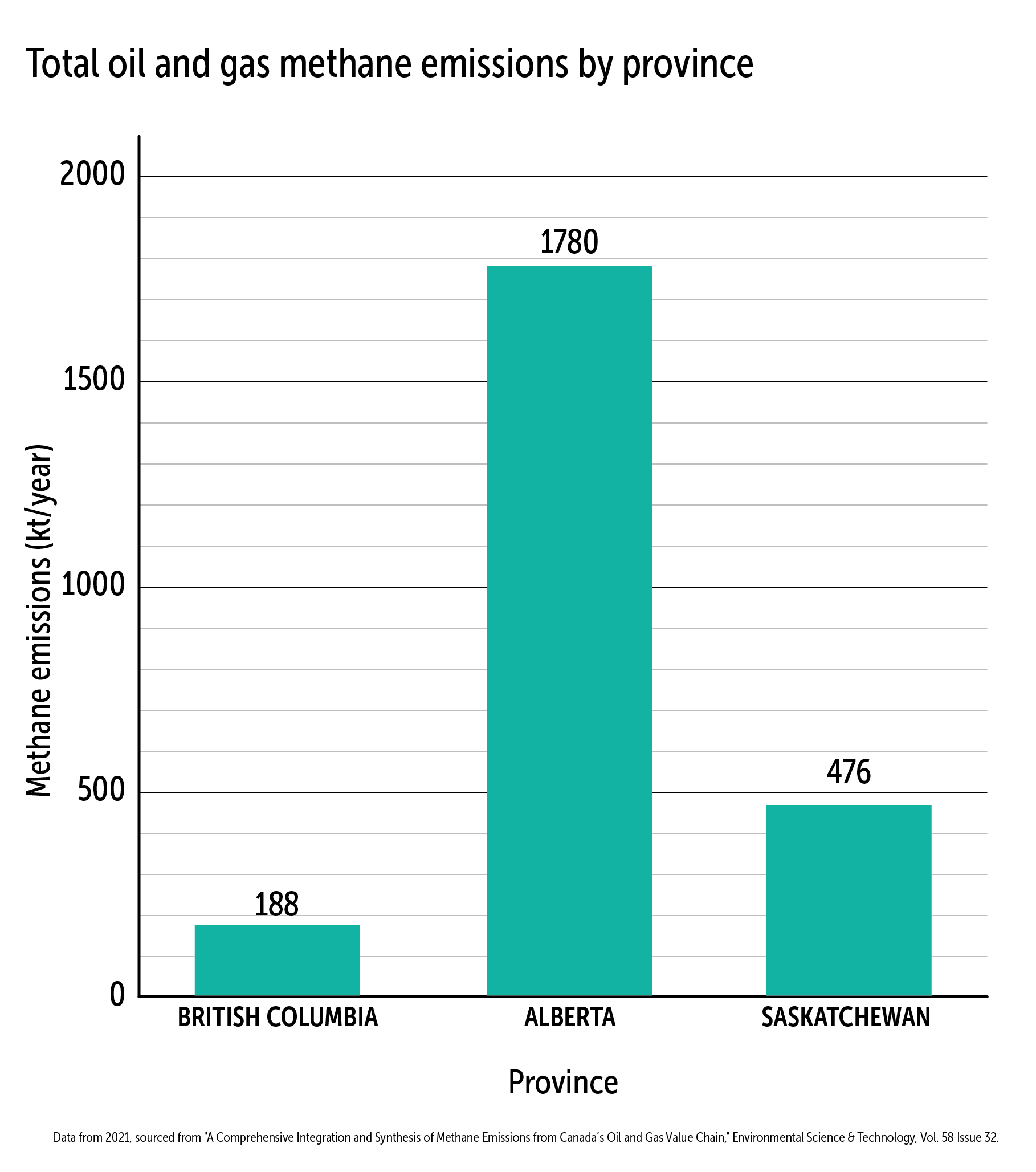

The methane loss rate doesn’t describe the amount of methane being emitted overall, only how much is lost versus captured. Saskatchewan accounted for 18 per cent of all of Canada’s oil and gas methane pollution, the scientists found.

Alberta, the largest crude oil producer and largest greenhouse gas emitter in Canada, also accounts for most of the country’s oil and gas methane pollution, at 68 per cent. While its methane loss rate for conventional oil and gas is relatively low, it is much higher for another form of production, oilsands mining, at 8.5 per cent, the scientists found. At oilsands mines, methane can escape from places like open-pit mines, upgrading facilities or tailings ponds.

The study did not take environmental impacts from other greenhouse gases like carbon dioxide, and industry byproducts like tailings ponds, into account, so does not claim to represent the “total climate impacts of different oil and gas production.”

Environment and Climate Change Canada has acknowledged historical estimates of the oil and gas industry’s methane pollution haven’t been accurate. The country’s recent national inventory produced by the federal government takes more scientific data into account, and scientists credit this research for leading to the government revising its past years’ estimates of methane upward.

Yet the department still runs into problems obtaining accurate methane measurements from oil and gas operations, a spokesperson told The Narwhal in an emailed response to questions about the study.

The issue remains virtually the same as the government described it a year ago: there’s just too much industry equipment to measure.

“The design of Canada’s regulations recognize that accurately estimating methane emissions from oil and gas operations remains a challenge…the industry in Canada includes tens of thousands of facilities, hundreds of thousands of wells and millions of components with the potential to emit,” the spokesperson wrote.

This makes accurately estimating emissions and writing suitable regulations a challenge, they said: rather than putting a hard limit on leakage, the government aims to “establish work practices and provisions that industry is required to follow.”

The government says it’s focused on fixing the problem. The department is “actively working with researchers” and reviewing up-to-date science and data, the spokesperson said, and expects to sign “a number of contribution agreements” this fall and winter with companies to help “accelerate” the accuracy of methane measurement and “advance science in this area.”

Canada is also hoping its new proposed methane rules will help.

While industry is already required to monitor for leaks, the government has said its new rules introduce “strict limits and controls on all key methane emissions,” as well as a tougher regime for leak inspections and an audit system for validating company results, among other restrictions.

The department’s full response to The Narwhal can be found here.

Despite the province’s clear problem with containing industry emissions, Canada’s tougher new methane rules, expected to be finalized in the coming months, may not end up applying in Saskatchewan.

The federal government has jurisdiction over methane emissions from oil and gas under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, but provinces can sign equivalency deals with the government so only their own regulations apply.

In September 2020, Canada signed a deal that exempts Saskatchewan from current federal methane standards, on the basis that its rules are equivalent.

That deal was already in effect when the measurement data for the province’s high methane loss rate was obtained in 2021.

The current agreement ends in 2024, and the federal government says it’s comfortable moving ahead with a new one — which would apply from 2025 to 2029 — because it believes Saskatchewan’s latest methane rules introduced in March are almost identical to the new proposed federal standards.

The scientific article on methane emissions was published this summer at the same time Environment and Climate Change Minister Steven Guilbeault was seeking feedback on the proposal to establish the new equivalency deal with the province.

The Narwhal asked for an interview with Guilbeault on Aug. 16 and again Aug. 19 but his office did not make him available before publication.

The federal government can exit any agreement, the spokesperson said, if it determines its proposed rules are no longer equivalent to the province’s rules. In this case, according to the terms of the proposed deal, the federal department would be bound by it until at least the end of 2026.

In one instance, such provincial equivalency deals have resulted in weaker oversight. In Alberta, a successful fossil fuel lobbying campaign in 2017 persuaded the former provincial government to delay and weaken its own methane rules, forcing the federal government to admit those rules were “less stringent” than its own standards even as it accepted them as “equivalent.”

On the other hand, an article in the scientific journal Communications Earth & Environment from November 2023 attributed the low methane loss rate in B.C. to “stronger regulations and enforcement” in that province compared with others.

Under current provincial regulations, more than 90 per cent of Saskatchewan’s heavy oil sites haven’t been required to measure their methane pollution, a senior research analyst told The Narwhal in 2023, but have instead been permitted to report an estimate.

Amanda Bryant, a senior analyst with the Pembina Institute’s oil and gas program based in Calgary, said the recent article’s findings “underline the importance of provincial action” on methane pollution.

“It’s important for Alberta and Saskatchewan to keep moving on methane, because Alberta is the biggest greenhouse gas emitter in Canada, and Saskatchewan has this enormous methane loss rate, as shown by this study,” Bryant said.

In past years, Saskatchewan has signalled support in the fight against oil and gas industry methane. In 2022, for example, it announced it had cut methane escaping or being burned off at oil producing sites by 64 per cent below 2015 levels.

But critics have been skeptical of the accuracy of Saskatchewan’s claims, since methane pollution has historically been underestimated in that province by up to 40 per cent.

Meanwhile the provincial government, led by the conservative Saskatchewan Party, has grown more recalcitrant about federal environmental initiatives.

In late 2023, the province criticized the new federal target to slash oil and gas methane emissions as “another example of federal overreach.” In April this year it argued its implementation will “hit Saskatchewan disproportionately harder than other Canadian jurisdictions.”

The office of Saskatchewan Energy and Resources Minister Jim Reiter did not respond to emailed questions on Aug. 22 and again on Aug. 27.

Oil and gas companies themselves have no excuses for allowing all of this methane to escape into the atmosphere, according to the International Energy Agency.

Cutting oil and gas methane pollution is “one of the most pragmatic and lowest cost options to reduce greenhouse gas emissions,” it wrote in a report released in March 2024.

“The technologies and measures to prevent emissions are well known and have already been deployed successfully around the world,” the agency wrote, while the cost to install such equipment “represents less than five per cent of the income the industry generated in 2023.”

In Canada, where oil and gas is the largest industrial emitter of methane, the sector made $63 billion in profit in 2022, the most recent year official figures are available, and Canadian oil production hit a record high in 2023.

However the country’s largest oil and gas lobby group, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, has argued the draft proposal for the federal rules “do not represent a workable path” to the 75 per cent target.

In comments to the federal government made in February, the lobby group said the proposed regulations are not “predictable,” in part because the technology required to adequately reduce methane emissions are not yet common, resulting in “extremely high costs but zero or near zero incremental emissions reductions.”

The Explorers and Producers Association of Canada, which lobbies on behalf of smaller and mid-sized oil and gas producers, said in its own comments that it has been “mostly supportive” of the government’s action on industry methane pollution, but argued some elements were “overly burdensome or unworkable.”

The Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and the Explorers and Producers Association of Canada did not respond to requests for comment before publication.

Part of the reason for Saskatchewan’s high methane loss rate is because it’s dominated by oil production rather than gas production, MacKay said, meaning methane is considered an incidental product, not a potential moneymaker.

“A lot of the gas that’s being produced there is often just a byproduct of the oil production, so if there’s no infrastructure on a well site to either capture or destroy that gas, and if it’s not producing enough to make it worthwhile to capture, it often just ends up in the atmosphere,” MacKay said.

In Saskatchewan, thousands of facilities dot the landscape that produce heavy oil, a type of thick crude oil that’s used for making asphalt and petrochemicals. At some of these facilities, methane bubbles to the surface inside tanks that contain a mixture of crude oil, sand and water. The industry’s technique has been to release the gas before it builds up excess pressure, then collect the oil left over.

The recent study does not directly attribute Saskatchewan’s 19 per cent methane loss rate to these specific types of heavy oil sites, MacKay said.

However, she pointed to another December 2023 study in the same scientific journal that found almost half of measured methane emissions in Saskatchewan were coming from heavy oil wells.

The latest study is the first time scientists have compiled measurement data from the past decade from different oil and gas sources in Canada to create a true “national picture” of industry methane emissions, MacKay said.

While the study represents the broadest compilation of methane measurement data to date, MacKay noted there are still many parts of the oil and gas sector’s methane emissions that haven’t been studied thoroughly.

For example, the study could not find direct measurements of emissions from the 250,000 kilometres of specialized pipelines in Canada that transport fossil fuels from wells and drilling sites to refineries or larger transmission pipelines.

Nor could the scientists find direct measurements of methane pollution from storage facilities for liquefied natural gas, data for local distribution systems for natural gas, or direct measurements of methane leaking from residential and commercial buildings that use natural gas for heating and cooking.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

I’ve watched The Narwhal doggedly report on all the issues that feel even more acutely...

Establishing the Robinson Treaties, covering land around Lake Huron and Lake Superior, created a mess...