Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Flying over northwestern Ontario in small airplanes, as part of his conservation work with Wildlands League, Trevor Hesselink noticed a peculiar pattern in the boreal forest below.

Amidst the emerald green of the coniferous forest, freckled with brilliant lakes and wetlands, were what Hesselink viewed as “scar lines” — persistent and widespread logging roads stitched together by barren rectangles.

“I trained as a land use planner so I tend to think about things spatially,” Hesselink told The Narwhal. “I realized I was actually seeing decades of logging with very similar patterns.”

Hesselink spent some time on Google Earth “scrolling around a little bit more and looking at it.”

Then he started viewing GIS overlays to get an idea of the ratio of clear-cuts in the large area around Wabakimi Provincial Park he regularly criss-crossed by air.

“And then I realized that I had something that others might not have seized upon,” explained Hesselink, policy and research director for Wildlands League. “And so I started this project.”

Hesselink’s project came to fruition today with the release of the 70-page report Boreal Logging Scars.

Sixteen years after logging ended at this site, logging scars in the area are still visible and visibly contrast with renewed growth. Photo: Trevor Hesselink

The report measures the previously undocumented long-term impacts of roads and roadside footprints — including landing areas, pull-offs, roadside pits and staging areas — from clear-cut logging in Ontario’s boreal forest, one of Canada’s great carbon sinks.

It found that Ontario has lost 650,000 hectares of productive forest — an area 10 times the size of the city of Toronto — over the past 30 years as a result of roads and other logging infrastructure.

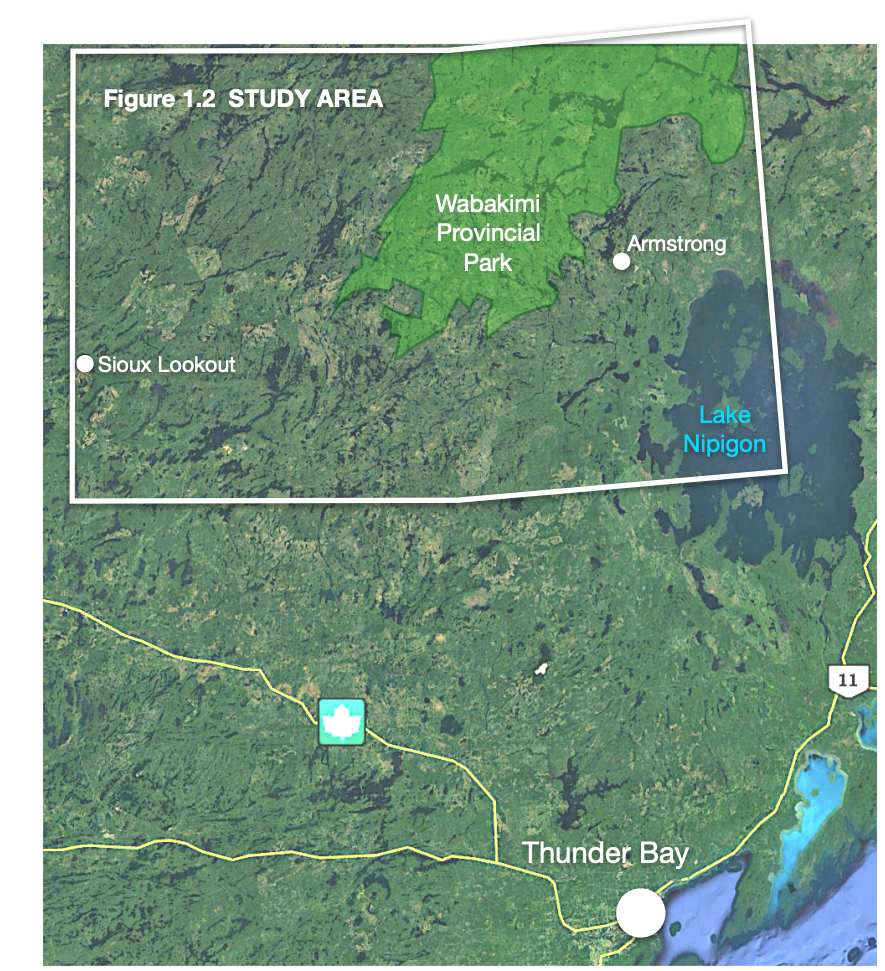

The study area surveyed by drone and documented in the report covers 35,000 square kilometres in northwestern Ontario. Map: Wildlands League

“The biggest finding is that these scars I was seeing turned out to be larger than I thought,” said Hesselink, the report’s lead author. “The other thing was getting on the ground and finding out just how barren they are, even in 30-year-old clear cuts that I visited.”

“Essentially there are fairly significant impacts — particularly when you think of it cumulatively, over a landscape — that fly under the radar.”

An abandoned branch road near Armstrong shows wide, unproductive roadside landings. Photo: Trevor Hesselink

Hesselink’s tent and truck in the boreal as he conducted his aerial survey. Photo: Trevor Hesselink

A detailed analysis of clear cut sites around the Wabakimi park area, undertaken in part through truck tours, hiking, mountain biking and drone surveys, showed roads and staging areas had such compacted soil that little grew there even 30 years after industrial logging.

But when Hesselink dug into deforestation statistics from the provincial and federal governments, he found roads and other areas with only scant vegetation were largely not counted in the data.

“The reality that roads and landings remain barren decades after logging — that is, de facto deforested — appears to have been largely ignored in forest management planning and reporting, land-use change accounting, wood-products life-cycle assessments, and forest-carbon policy discussions,” the report concluded.

The main culprit is what Wildlands League calls a “deeply wasteful practice” resulting from what is known as full-tree harvesting. Entire trees are dragged from their stumps to roadsides, where merchantable logs are stripped of branches and tops, creating large volumes of waste.

“If they were reporting all those logging scars it would make Canada’s [deforestation] numbers seven times higher just for Ontario,” Hesselink noted, adding that only 17 per cent of Canada’s logging takes place in the province.

Logging waste is piled along the roadside, inhibiting renewed tree growth. Photo: Trevor Hesselink

That has serious implications for Canada’s carbon debt and carbon reporting, according to the report, whose release was timed to coincide with the UN Climate Change Conference opening in Spain this week.

The logging scars created by roads and landings, studied across 27 clear cuts over 35,000 square kilometres of boreal forest, occupied an average 14.2 per cent of the area logged, the report found.

Based on that average, the study estimated that approximately 21,700 hectares of boreal forest are deforested each year in Ontario through logging infrastructure.

Because Ontario’s boreal forest is such a valuable carbon sink, if the rate of deforestation continues at its current pace, the report estimates it will represent the loss of 41 megatonnes of stored carbon dioxide.

“That’s about the same as a year of Canada’s automobile emissions,” Hesselink noted. “[It’s] fairly significant.”

The long-lasting deforestation of the boreal forest has implications for species at risk such as caribou, Hesselink also pointed out.

The sparse growth along this forestry road is typical even 10 years after full-tree logging and slash-pile burning have ended. Photo: Trevor Hesselink

“These logging scars are very significant for caribou in the sense that the game plan is that after 40 years in Ontario it’s expected that they would have regrown caribou habitat … that after about 40 to 45 years, caribou will come back to a cutover.”

But the persistent roads and barren staging areas bring more moose and deer into areas, in turn attracting more wolves, a main predator of caribou, Hesselink noted.

“And the other piece of that is that you’re opening up sight lines which makes predation easier … you also have landings that make that road about five times wider than the road itself.”

While the report focused on Ontario, it pointed out that B.C. and Alberta have similar industrial logging practices.

“It might be time to reconsider the way we do forestry,” Hesselink said. “We have a sector that’s barely staying afloat as it is … it’s struggling.”

Hesselink, a land-use, geospatial, and environmental

policy professional, pilots his drone. Photo: Trevor Hesselink

After logging, waste piles stacked alongside forestry roads are often burned. Photo: Trevor Hesselink

Canada should also reconsider its relationship with virgin forest as well, he said.

“We don’t have much of it left. The trade-offs that these logging scars represent are very important. I’d like to think that everybody could be considering those on a regional basis and come out with a way of making better products that create more value and more jobs and that also can help us mitigate climate.”

Globally, the boreal forest contains about one-half of the planet’s terrestrial carbon stocks. About one-fifth of the world’s boreal forest is found in Canada.

Why Canada’s boreal forest is gaining international attention

Researchers have found that northwestern Ontario’s managed forests stored almost three billion tonnes of carbon in 2000.

“For these reasons, what happens in this forest has the potential to significantly influence the global carbon balance,” the report found.

Wildlands League is asking the federal government to revise rules for monitoring deforestation to address “the substantial risks and impacts” from logging roads and landings in the boreal forest. It’s also calling on the government to review and remedy underreporting of the carbon impacts from Canadian logging.

“We’ve been told over and over that Canada has a near zero deforestation rate,” Wildlands executive director Janet Sumner said in a statement.

“And now we know. Canada does indeed have a deforestation problem and one we need to fix.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...