Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

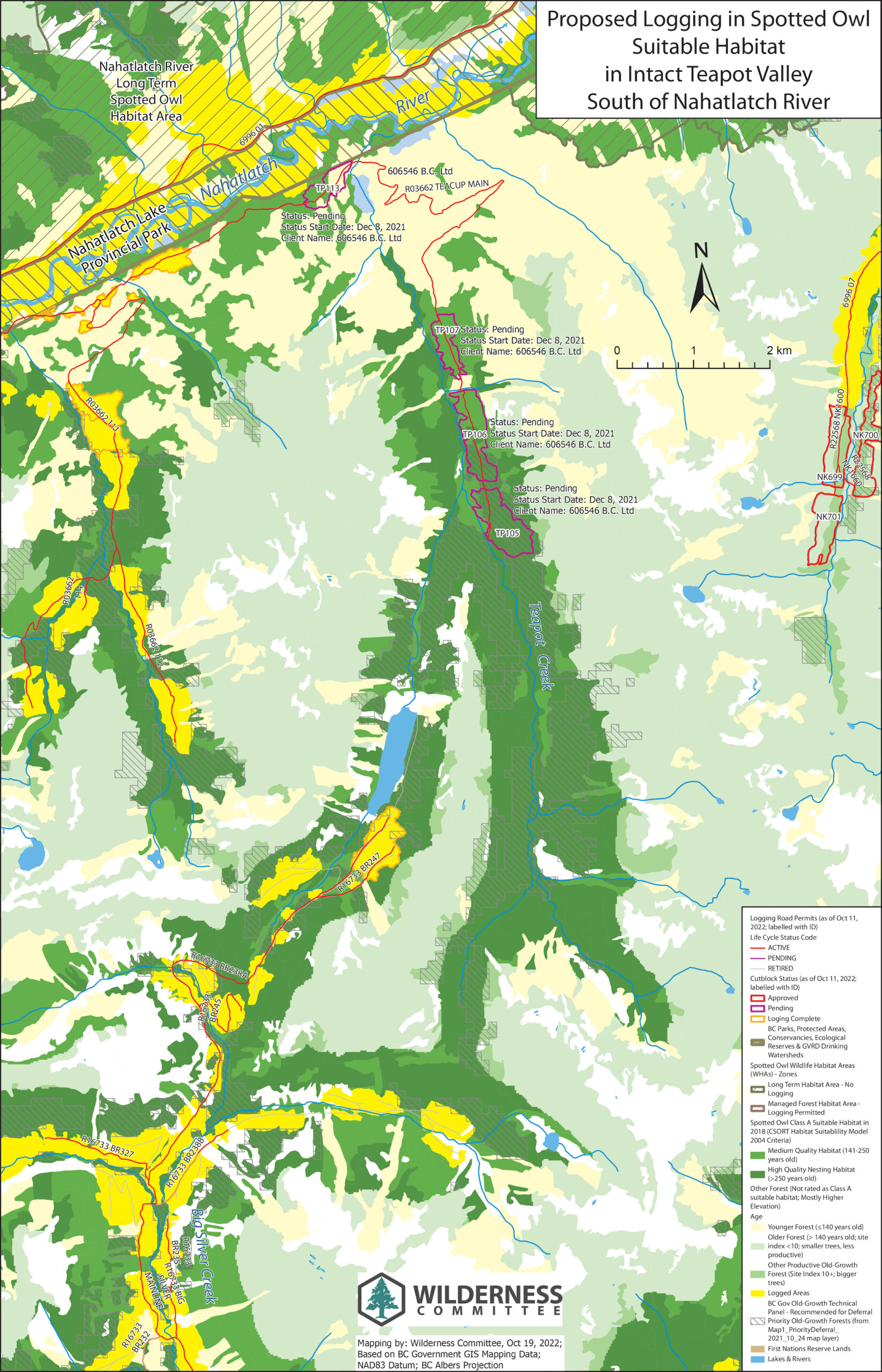

In January, Joe Foy was scrolling through a B.C. government mapping platform, looking at habitat for the endangered spotted owl, when he noticed something different. “Lo and behold — four cutblocks,” he said.

The pending logging cutblocks were near the Fraser Canyon in southwest B.C., in a “mystery valley” largely unknown to Foy, the protected areas campaigner for the non-profit group Wilderness Committee. “I had a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach,” he recalled. “It was a bit of a despairing moment.”

Foy later bushwhacked into the heart of the valley with camping gear, a drone and a GoPro camera. He found a beautiful, intact old-growth Douglas fir and red cedar forest — a rarity in the heavily logged Fraser Canyon region.

The valley, called Teapot, contains habitat suitable for the northern spotted owl, a species in critical danger of becoming extinct in Canada following decades of industrial logging in its mature forest habitat.

Earlier this year, only one spotted owl remained in Canada’s wild. About 30 spotted owls, including owls captured from the wild, live in aviaries at an experimental breeding centre in Langley that is funded by the B.C. government.

Further sleuthing by the Wilderness Committee revealed 448 additional logging cutblocks — overlapping fully or partially with spotted owl habitat — were recently approved by the B.C. government or are pending approval.

Some cutblocks, including two in the Teapot Valley, overlap with areas the B.C. government has identified as a priority for old-growth logging deferrals. The deferrals are areas set aside from logging on a temporary basis, pending potential protective measures in the future.

At least five cutblocks sit close to areas the provincial government has prioritized for the release of captive-bred spotted owls — an event promised for more than a decade and realized for the first time in August when three owls born at the breeding centre were set free in the Fraser Canyon region, with tracking devices to monitor their whereabouts.

Foy called the discovery of the logging plans “part of the continuing shock and horror at the clashing of all these different government policies.”

“I don’t accept it,” he told The Narwhal. “This is wrong.”

With logging maps in hand, the Wilderness Committee turned to the environmental law charity Ecojustice for help. On Oct. 25, Ecojustice, acting on behalf of Wilderness Committee, petitioned federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change of Canada Steven Guilbeault, demanding an emergency order be issued under Canada’s Species at Risk Act to save spotted owls.

The Act allows the federal government to step in if it believes there is an imminent threat to the survival and recovery of an endangered species. An emergency order gives Ottawa the power to make decisions that normally fall to provincial governments — such as whether to allow logging in Teapot Valley, identified as spotted owl habitat on B.C. government maps.

Ecojustice lawyer Andhra Azevedo said Guilbeault must take immediate action to protect spotted owl habitat and allow the species a chance at recovery. “What we’ve seen since 2006 is just this continued decline of spotted owl populations — down to what was one, and now has luckily at least become four. But still an incredibly low number,” she said in an interview.

“B.C.’s promises have just not held up. They haven’t protected enough habitat for owls, and they’re continuing to not protect habitat for owls.”

The B.C. government says it has set aside enough territory to support a self-sustaining population of 125 spotted owl breeding pairs in the future. Wilderness Committee disagrees, pointing to the owl’s demise as proof that the territory is far from sufficient.

Northern spotted owls are a medium-sized raptor with chocolate-brown eyes and namesake white spots. They evolved with the old-growth forests of the Pacific Northwest and northern California and can’t exist in the wild without large trees.

The owls nest in “stovepipes” quilted with fir needles, where wind has knocked off the crown of an old tree, or in cavities formed by broken branches. Old trees provide shelter and camouflage when the owl is not in the nest. Spotted owls prey largely on flying squirrels and bushy-tailed woodrats — other denizens of old-growth forests — although they will also eat birds, mice, voles, frogs and spiders.

The owls are known as an indicator species: if spotted owl populations are healthy, the ecosystem is too, and can support a diversity of wildlife. And if they’re not, it indicates that other species are likely in decline as well.

Biologists estimate that 1,000 spotted owls nested in B.C. over a century ago, not including juveniles and chicks. By the early 1990s, following industrial logging and settlement, only about 100 spotted owls remained in the province, the only place in the country where they are found.

As numbers continued to drop, the owl was listed as endangered under Canada’s Species at Risk Act, setting off a long chain of events that highlights both the promise and the failure of the Act.

“The B.C. government is guilty of approving logging in spotted owl habitat,” Foy said. “But Canada has also been guilty of foot-dragging and hand-wringing while this species is being logged to death.”

Species listed under the Species at Risk Act are the subject of a recovery plan that includes mapping and action to protect critical habitat — the habitat necessary for the survival or recovery of a species. But that didn’t happen for the spotted owl, despite a 2007 deadline. Fifteen years later, the process remains stalled.

“The difficulty with our species at risk protections is that often it happens in consultation between the federal and provincial governments,” Azevedo said. “And so, when the provincial government doesn’t want to take action, because it gets in the way of logging, they can slow down the process a lot. And that’s what we understand is happening right now — and has been happening for the last 15 or so years.”

B.C. lacks stand-alone legislation to protect biodiversity or species at risk of extinction. In 2017, the B.C. NDP campaigned on a promise to enact endangered species legislation but reneged on its pledge once elected to office. That leaves Ecojustice with only one option — to use provisions in the Species at Risk Act to protect the spotted owl and its habitat.

This is not the first time Ecojustice has demanded a federal emergency order to protect spotted owls. A petition was submitted in 2006 by Ecojustice’s predecessor, on behalf of the Wilderness Committee.

Following reassurances from the B.C. government that it was taking steps to protect the owls and their habitat — including setting up a captive breeding program and identifying critical habitat — the request for an emergency order was not granted.

“B.C. made a series of promises that essentially were to protect more habitat and to raise captive bred spotted owls,” Foy said. “That headed off the emergency order. … Now it’s 2022. B.C. never did set aside the critical habitat needed to make spotted owls recover and to make themselves sustaining. And so, we’re back. Oh, and there’s one wild spotted owl left and three have just been released from the captive program. But we’re back. And we say it’s an emergency.”

In 2020, provincial government biologists found a breeding pair of spotted owls in a provincial wildlife management area, bisected by a logging road, in Spuzzum Valley. Over two years, the owl pair hatched three chicks, which were captured by government biologists and taken to the breeding centre.

Plans for new old-growth logging beside the Spuzzum Wildlife Management Area, coupled with the discovery of Canada’s last breeding pair of spotted owls, prompted a second petition to the federal government two years ago. Submitted by Ecojustice, on behalf of the Wilderness Committee, the petition again asked the federal government for an emergency order to protect spotted owls and their habitat.

In response, early last year, B.C. and Ottawa struck a deal to defer logging in Spuzzum Valley and the nearby Utzlius Valley as the first step in a bilateral nature agreement aimed at strengthening conservation efforts in B.C.

For B.C.’s NDP government, whose environmental policies are under scrutiny following a controversial and divisive party leadership acclamation, the timing of the latest petition to Guilbeault could not be worse.

The petition was filed just four days after the government announced the release of the three captive bred owls in collaboration with Spuzzum First Nation, calling it a “monumental step forward” for the conservation of endangered species in B.C.

“We are doing everything we can to help spotted owls recover in B.C., including running the world’s only spotted owl breeding and release program for this critically endangered species,” Minister of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship Josie Osborne said in a news release that included a link to a video about the release.

“During my visit to the Langley breeding facility in July, I was incredibly impressed by the deep commitment of everyone involved in helping these rare and beautiful birds achieve a self-sustaining population,” the minister said.

The provincial government described the release as a “carefully planned, collaborative, government-to-government process that incorporated Indigenous Knowledge and guidance from Spuzzum Nation Chief James Hobart.” What wasn’t mentioned in the news release is that Spuzzum First Nation is calling for a moratorium on old-growth logging in its territory to protect spotted owls and old-growth cedar trees.

The three owls were moved from the breeding centre to aviaries in a forest in the Fraser Canyon region and fed for several days to help them adapt to their new environment. “Eventually, the doors were opened so the owls could leave the cages and hunt on their own,” the news release said. “The development of feeding skills was a precondition of the release, with the owls needing to demonstrate their ability to capture live prey and maintain a stable body weight.”

Hobart said he is proud of his nation’s stewardship role in the return of owls to the wild and looks forward to the sound of spotted owls “calling in their own woods and realizing they have found their way home.” The owls are powerful beings, recognized as “messengers to our spirit world and of our physical world,” Hobart said in a statement. “They are species that are indicative of the health of an environment.”

In an emailed statement, the B.C. Ministry of Land, Water and Resource Stewardship said it is aware of the Ecojustice petition, reiterating that the government is doing everything possible to help spotted owls recover.

The province understands the importance of protecting critical spotted owl habitat from activities that could disrupt the birds’ recovery, the ministry said, adding that decisions are based on the best available science and Indigenous Knowledge to support the birds’ recovery to a self-sustaining population in B.C.

The timing of the emergency order petition also risks embarrassing the federal government globally, as Canada is hosting the 15th United Nations Biodiversity Conference in Montreal in December. The conference, known as COP15, will bring together thousands of delegates from around the world to hash out a new agreement to reverse global biodiversity loss.

“I think what this petition highlights — and what the long history of spotted owls highlights — is the promise of the Species at Risk Act and the fact that it was supposed to be part of Canada implementing the Convention on Biological Diversity, which is what this conference is about,” Azevedo said.

The conference comes as scientists around the world warn we are witnessing the sixth mass extinction event in the planet’s four-billion-year history. As many as half of all species on the planet may be headed toward extinction in the next 30 years, largely due to habitat destruction.

At a September lead-up event to COP15, Prime Minister Justin Trudeau spoke about the shared global fight to halt biodiversity loss before it goes any further.

“No one here needs to be reminded that once a species is lost, it’s lost forever,” Trudeau said. “Once we’ve done too much harm for too long to old-growth forests or oceans, they may be beyond repair. I don’t say this to make us lose hope. I say this to remind us of what’s at stake. And to remind us that we must all do our part, right now, to make a difference.”

Azevedo said the level of urgency required to address the biodiversity crisis is not reflected in either federal or provincial responses to the spotted owl’s impending Canadian extinction. In the United States, following a prolonged legal battle, the government designated almost four million hectares of critical habitat for the northern spotted owl. Today, although the survival of the species is far from secure, about 2,000 spotted owl pairs nest in Washington, Oregon and northern California.

“I think Canada has a fair bit to answer for its response to species at risk, and to really demonstrate that there is a need for newer biodiversity legislation in Canada that protects ecosystems and biodiversity as a whole — and hopefully get ahead of situations before we get to the point where we’re talking about the number of owls that we can count on one hand.”

Ecojustice has demanded the federal government respond to the petition by Nov. 24.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits