The Narwhal picks up four Canadian Association of Journalists award nominations

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau and B.C. Premier David Eby beamed with praise as they celebrated the Haisla Nation in late June.

The northwest B.C. First Nation and its business partner, Pembina Pipelines Corp., had just announced a final investment decision on their proposed fossil fuel project — meaning construction will proceed.

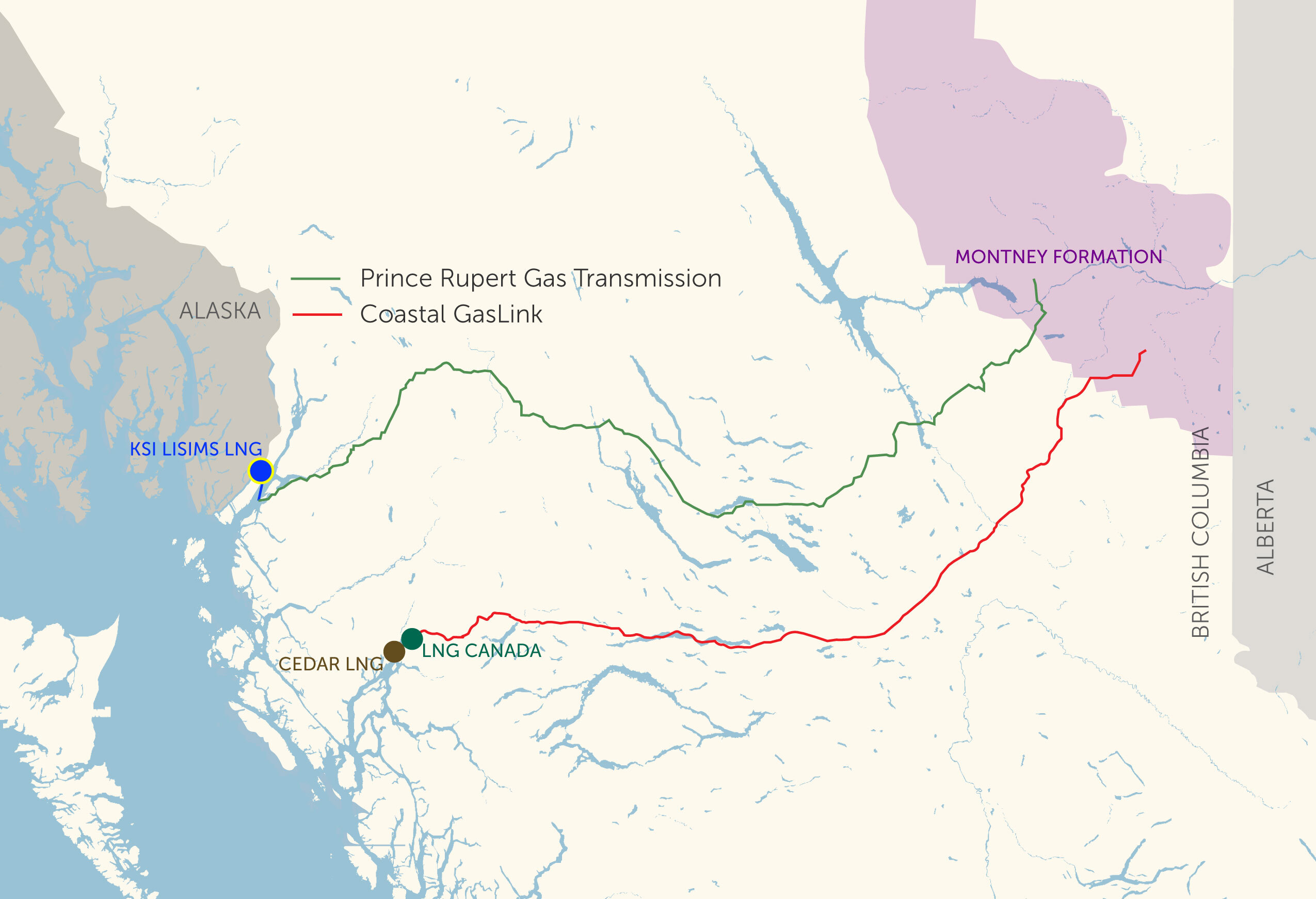

Haisla Nation has a 51 per cent stake in the project, Cedar LNG, while Pembina controls the remaining share. The project consists of a new natural gas liquefaction plant in Kitimat, B.C., which will receive gas shipped from the province’s northeast through the Coastal GasLink pipeline and cool it to liquid form at -162 C, reducing its volume for export.

Calling it the “first project of its kind,” Haisla elected Chief Councillor Crystal Smith said the liquefied natural gas (LNG) project is “trailblazing a path” toward economic independence.

Eby and Trudeau appeared to agree.

“Cedar LNG is a shining example of how natural resource development should work in our province — in full partnership with First Nations and with the lowest emissions possible,” Eby said in a video.

Trudeau echoed those remarks, calling the project and partnership “a model for economic reconciliation.”

“The world is evolving,” he said, also in a video statement. “The way we get our energy is evolving. The way we do business is evolving. Everyone involved in this project saw this and you all saw the opportunities that come with it.”

As political leaders lauded the decision, another business executive, François Poirier, was also celebrating the announcement. Poirier is CEO of TC Energy, the Calgary-based fossil fuel giant that built the Coastal GasLink pipeline, which will supply fuel for the Cedar LNG project.

In a statement, Poirier said the partnership between a First Nation and a fossil fuel company had “redefined the future of energy development in North America.”

“Through Indigenous-ownership, Cedar LNG will create opportunities that will support Indigenous and local communities in northern British Columbia and deliver benefits to the world by meeting global demand for more secure, affordable and sustainable energy,” Poirier said, calling the project a “transformative moment for Indigenous-led energy projects in Canada.”

While both Eby and Trudeau described the project as a “partnership” and a step toward reconciliation, TC Energy executives also discussed internally what this type of partnership means to them. The Narwhal has learned that in at least one case this included a conversation about how Indigenous communities and other stakeholders could be leveraged by fossil fuel companies as a “force multiplier” to increase the value of major projects and secure approvals from governments.

The Narwhal reviewed more than two hours of leaked recordings of internal TC Energy calls that took place in February and March and sent dozens of questions to the company and government about claims made by staffers working for the multinational energy corporation.

On one of the recordings of internal calls obtained by The Narwhal, Natasha Westover, a TC Energy staffer based in Vancouver who manages the company’s external relations team in B.C., described the political landscape on the February call.

“I know at least from our provincial government here that that is going to be the narrative going forward,” she said. “Indigenous LNG is going to lead in terms of public narratives for our governments in getting these projects approved.”

She did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions prior to publication.

TC Energy did not answer specific questions about comments made on the recordings and told The Narwhal some statements made by one of the employees on the calls were “inaccurate” and “portray a false impression” of how the company does business.

Patrick Muttart, TC Energy’s senior vice-president of external relations, said the company works to build trust with communities and apologized to “all our partners, stakeholders and rights holders for any impact on our longstanding relationships.”

“For us to build and operate major infrastructure projects, we need to earn the support and trust of local people and local communities,” Muttart wrote in a statement provided to The Narwhal. “That is what governments, Indigenous communities and the public expect from us and it’s the right thing to do.”

Days after The Narwhal first published details of TC Energy’s recorded meetings, Chief Greg Nadjiwon of Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation in Ontario received a call from TC Energy officials. “They just called to make me aware that I’ll probably be contacted by The Narwhal about this,” he said in an interview.

Saugeen Ojibway Nation, which includes Chippewas of Nawash and Saugeen First Nations, is currently deliberating offering a green light to another TC Energy project: a pumped storage and hydroelectric project in Meaford, Ont. Alongside TC Energy and energy officials, the nation has been informing their community members about the massive project to draw (or pump) nearly 7,000 Olympic-sized swimming pools worth of water in and out of Georgian Bay to generate and store electricity.

TC Energy previously told The Narwhal the first people they approached about the project in 2019 was Saugeen Ojibway Nation. They’ve been talking ever since.

The First Nation is conducting its own environmental assessment to understand the impacts the project may have on and around the bay. In this process, Nadjiwon said he has always been “careful,” acutely aware of historically tense and unbalanced relationships between energy companies and First Nations. But watching a surge of energy investments, he’s also trying to change this relationship to benefit his community.

But to Nadjiwon, the leaked recording illustrates why he must walk even more carefully in this relationship.

TC Energy’s history with some Indigenous communities is fraught. To construct its Coastal GasLink pipeline, the company secured agreements with elected First Nations governments in northern B.C. but did not get consent from Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs.

Opposition from the chiefs and their supporters led to years of conflict, and police and Supreme Court intervention. Widespread solidarity protests in early 2020 shut down Canadian ports and railways for weeks.

On the leaked recordings, Liam Iliffe — a TC Energy executive who resigned a few days after The Narwhal approached him in June for an interview — stressed the company’s success in building energy infrastructure hangs on Indigenous involvement.

“All of this effort is for naught if there isn’t Indigenous support or at least Indigenous non-objection,” he said on a call in March. “A government of any stripe, in British Columbia particularly, is not going to push projects forward unless there’s Indigenous support.”

The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, legislated both federally and in B.C., affirms Indigenous people’s right to self-determination and to provide free, prior and informed consent to any development on their lands. In other words, companies are required by law to gain Indigenous consent before they start building.

Iliffe used the word “validators” when talking about how the company should create relationships, including with Indigenous communities, that serve the company’s goals.

“As cabinets go and governments go and decision-makers go, we always have to make certain that we’re shoring that up and bringing validators through our relationships with communities, Indigenous people, Indigenous leaders and the general public to government to ensure that the government is confident that they can make the positive decisions without affecting their voter base, which drives a lot of decision-making,” he said.

Dave Forestell, previously a senior federal Conservative political staffer who served in former prime minister Stephen Harper’s government, said on the call that company executives need to ask themselves, “How do we make it in the government’s interest to do something?”

“You think first about what would encourage somebody to consent or ideally support and advocate for this project,” Forestell said. He added the goal is to find ways to get Indigenous support “while preserving, or ideally enhancing, the economics of the project.”

“To be clear, what I mean is when you have early Indigenous support on a project, de facto the economics of the project are enhanced because one of the single greatest risks we face as a company is regulatory delays.”

Forestell did not respond to an interview request and emailed questions from The Narwhal.

Muttart, TC Energy’s senior vice-president, said the company believes Indigenous communities should benefit from projects.

“We also believe the projects of the future should be built by Indigenous employees, serviced by Indigenous businesses and owned by Indigenous Nations,” he said in his emailed statement. “Reconciliation with Indigenous Peoples requires true participation in Canada’s resource economy.”

Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chief Na’moks told The Narwhal he believes First Nations leaders are sometimes used by fossil fuel companies to advance industry initiatives and suggested the comments on the recording are not surprising.

“When they start to refer to [Indigenous Peoples] as ‘validators’ they are taking the path of least resistance,” he said in an interview. He said fossil fuel companies are “targeting people that are in economic need,” thereby forcing First Nations into agreements. Once those agreements are secured, he said he has seen companies use Indigenous leaders to repeat industry talking points.

In the recording, Iliffe noted how TC Energy’s community outreach around the Meaford project in particular is paying off. “The tactics that we use to garner and gain support … they work everywhere,” he said, providing examples also in B.C. “They’ve been used sometimes just to achieve non-objection … We find ourselves in places where often listening is the best tool so that we can adjust and align.”

After hearing how Iliffe described Indigenous leaders as “validators” of energy projects, Nadjiwon said, “I don’t know the man, but he needs to validate all that.”

“This is our homeland. We want to be counted in. We want a place at the table, to be taken seriously. Not as validators.”

Iliffe didn’t respond to The Narwhal’s questions asking for further context and clarification. But he told The Narwhal in a statement that some of his comments referred to events that did not actually happen. He did not confirm which parts of his comments were accurate.

TC Energy did not comment on the specifics of what Iliffe said about Indigenous engagement in Meaford. Since 2019, the company has sponsored bingo nights and information sessions with dinner for members of the First Nations. It has paid for bus tours to similar energy projects in Michigan and Massachusetts. It has also organized a boat tour of the bay and a visit to the project site.

But Nadjiwon is clear: TC Energy has no influence over him, and he still trusts the company officials he has been speaking to, albeit with even more caution.

“I’ve told them many times: they can’t use me and my people.”

Chief Greg Nadjiwon, Chippewas of Nawash Unceded First Nation

“If I didn’t, I’d walk away,” he said. “I’m not a partner of TC Energy. We’re working toward that. Maybe. But I’m sure they have a fear that there could be a bump in the road that isn’t capable of being resolved … They’re under the microscope with Indigenous people, and they know that.”

“I’ve told them many times: they can’t use me and my people,” he added. “If there’s one bad apple on the tree, you don’t cut down the whole tree.”

B.C. is poised for the biggest fossil fuel boom in the province’s history. The BC NDP government, elected in 2017, has continually promoted the liquefied natural gas export industry, championing the LNG Canada project and offering billions of dollars in subsidies to some of the most profitable multinational oil and gas companies in the world. LNG Canada, a consortium of five multinational oil and gas companies, including Shell, will be the first liquefied natural gas export project in the country when it begins commercial operations next year in Kitimat.

Chief Smith, with the Haisla Nation, has long been a vocal supporter of the liquefied natural gas sector. She is a member of several organizations advocating for LNG development and worked to secure financial benefits for her community from the LNG Canada facility.

In January, addressing attendees at the annual BC Natural Resources Forum in Prince George, B.C., she explained how those benefits and advancing the Cedar LNG project start to address an economic imbalance between settlers and Indigenous Peoples.

“Something I’m profoundly impacted by is our ability to fund the programs that really connect our people to their culture and our language, a language that has virtually disappeared in my generation,” she said. “We are reigniting our potential through culture and language and that is perhaps the most powerful thing of all.”

Smith did not respond to an interview request from The Narwhal.

An unidentifiable speaker on the leaked audio from TC Energy’s February call said Indigenous support for the liquefied natural gas sector is not unanimous in B.C.

TC Energy recently completed construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline and is getting ready to start building its Prince Rupert Gas Transmission project, a 800-kilometre pipeline the company is in the process of selling to the Nisga’a Nation. TC Energy secured agreements with some First Nations governments along the route of the pipeline when it first sought — and received — provincial approval in 2014, but not all communities are supportive.

The unidentified speaker said U.S. President Joe Biden’s pause on liquefied natural gas exports was rippling into communities in British Columbia and asked Edward Burrier, a former White House staffer who is now TC Energy’s director of public policy, for advice.

“I support the B.C. team and so obviously we’re in the thick of it with LNG,” the speaker said. “As we go out and start to talk to nations again about the … Prince Rupert natural gas transmission line, we’re really having, in some instances, having problems getting traction with the nations. I think you’re bang on when you say the pause in the States is going to spur on, you know, give more power to people that don’t want to talk to us.”

Burrier characterized Indigenous involvement in fossil fuel development as a competitive edge industry can use to advance projects, describing his observations from the LNG 2023 conference that was hosted in Vancouver.

“Every CEO sits up there and talks about these LNG projects around the world and they all sound the same. But then Chief Crystal got up and said, ‘I’m with Haisla Nation and we used to have to manage poverty, now we have to figure out how to manage wealth.’ ”

“That’s the force multiplier, to use one of the words of the hour, that we have on our side.”

Burrier did not respond to The Narwhal’s questions about his comments and the recordings.

— With files from Mike De Souza

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...

Locals in the small community of Arborg worry a new Indigenous-led protected area plan would...