Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

In the middle of snow-speckled fields just off the Crowsnest Highway near Taber, Alta., rusting barrels dot the landscape, among storage tanks and lines of pipe. Soft plastic tape that has peeled off pipes ripples in the cool October breeze.

This site is now classified as an orphan, ever since the company that owned it, Neo Group, went bankrupt three years ago. The site is entirely surrounded by crops — mostly potatoes.

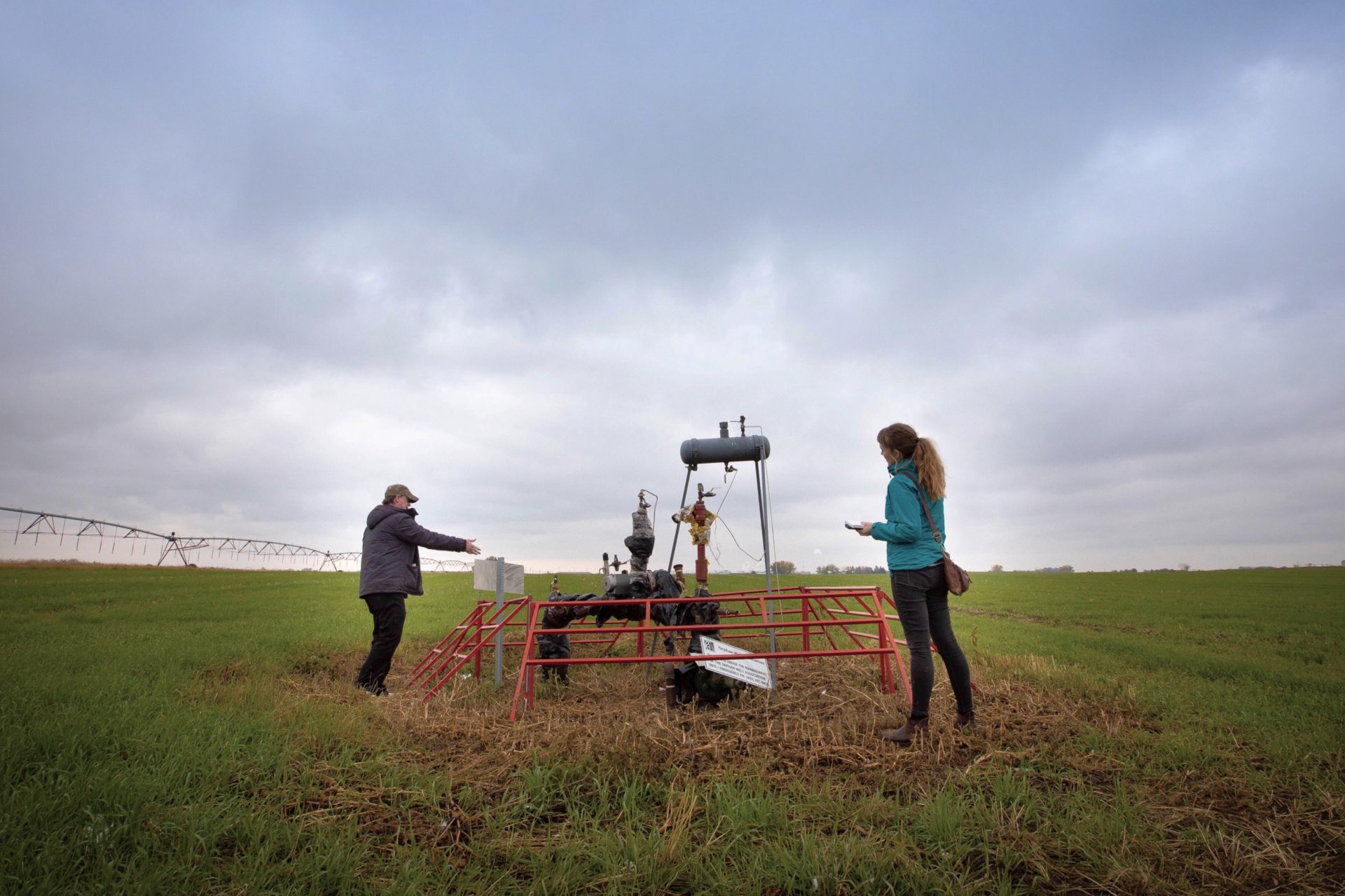

Daryl Bennett, who was born and raised in Taber — his family homesteaded in the area in 1903 — gets out of the vehicle to look around. He’s a director of a local group called Action Surface Rights, which describes itself as “dedicated to helping fellow landowners understand and navigate the maze of government and industry processes.”

He points out the site’s wellhead and flare stack, listing possible hazards: soil contamination, dust, issues with farming, invasive weeds. Then he gestures to the adjacent field, full of potatoes.

“If there’s a leak and it gets into the potato crop, it’s going right there into the French fry factory,” he says.

The site is on a list of facilities under the management of the Orphan Well Association entitled “Orphan Wells to be Abandoned,” where it has languished for at least two years. The list currently contains 2,000 wells that have yet to be properly sealed — known in the industry as “abandoning” — and whose owners are now bankrupt.

Daryl Bennett at an orphan site near Taber, Alberta, left behind by a bankrupt company. The emergency number posted at the site was no longer working. “Who do you call?” Bennett wondered. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

Beyond the barrels and pipes, there are likely other hazards below the surface. Data shows the total depth of the well at the Taber facility is 407 metres, so the risks reach far below ground level.

The problems facing farmers are numerous, Bennett tells The Narwhal. Farmers must ensure their irrigation systems can pass over wells without hitting them, farm around the roads that lead to wellsites, deal with the dust and weeds that come with disturbed soil, and worry about contamination of their crops — and they often face long, paperwork-filled fights to claim the annual rent they’re owed by energy companies.

Before he climbs back into the vehicle, Bennett wanders over to the entrance of the site and looks at the now-defunct company’s sign, still hanging prominently on a small shed. “In case of emergency, please call,” it reads, listing a toll-free number for the bankrupt company.

The Narwhal called the toll free number listed and was met with an automated message stating, “the number you have reached has been changed.”

“If there is a problem, who do you call?” Bennett asks. “There’s nobody there.”

Bennett is part of a movement of landowners concerned the government — and the Alberta Energy Regulator in particular — is not only struggling to deal with Alberta’s long-standing well issue, but that the organization is propping up a beleaguered industry without requiring the necessary assurances that wells will be cleaned up in the future.

Critics worry that not only are orphan wells already sitting neglected in farmers’ fields across the province, but that a whole new wave of inactive wells are poised to be thrust onto the Orphan Well Association — and that, increasingly, taxpayers may be forced to shoulder the bill.

It has been estimated that at the current rate of spending, it would take 177 years to clean up the province’s inactive, suspended, abandoned and orphan wells.

Daryl Bennett, a director with Action Surface Rights. Bennett has spent years trying to make sure his neighbours are fairly compensated by the companies that drill wells on their land. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

Bennett sees no shortage of possible hazards at orphan sites like this one, including soil contamination, dust, issues with farming and invasive weeds. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

In theory, there is a system designed to ensure wells are cleaned up once companies are done with them, ensuring there is money available for proper reclamation, even if companies go bust.

But critics worry the system has been perverted to the point that the Alberta Energy Regulator is now propping up the province’s oil and gas companies through accounting systems that exaggerate assets and underestimate liabilities by using outdated information — meaning companies are able to drill new wells despite questions around their ability to pay for their eventual cleanup.

“They’re putting the best spin on it,” farmer and Action Surface Rights chairman Ronald Huvenaars told The Narwhal of the regulator’s methods. “If you went to an accountant and had it audited, there’s no way an accountant would ever sign off on that.”

Farmer and Action Surface Rights chairman Ronald Huvenaars on the driveway of his family farm, Pigs Fly Farms. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

Huvenaars stands beside active infrastructure on his family farm. Increasingly, he’s worried that companies in Alberta aren’t taking into account the costs they’ll have to pay to clean up wells like this one when they reach the end of their productive life. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

As one briefing paper published by the University of Calgary put it, “This type of system works well during an oil boom but not so well during an oil bust.”

The trouble is, the Alberta Energy Regulator is still acting like it’s in an oil boom.

“It’s just kicking the can down the road,” Huvenaars said. “It’s kind of like a snowball, it’s getting bigger and bigger as it rolls.”

And that, he said, leaves landowners feeling powerless when it comes to industry activity on their land.

Conventional wells are drilled through layers of earth — soil, layers of rock, groundwater aquifers — to reach a pocket of oil or gas within a rock formation. When they’re successful, the deposits are tapped and brought back to the surface — through a steel pipe that runs the depth of the well, surrounded by concrete — without contaminating any of the layers above.

Once the well’s productive life has ended, a company can choose to suspend the well (temporarily take it out of service), decommission it completely by fully sealing it off (known as abandoning), or leave it to sit, unsealed, indefinitely. A well becomes an “orphan” if the company that owns it goes bankrupt, whether it is safely sealed or not.

Alberta has no time frames on when a well should be properly sealed and reclaimed, unlike other jurisdictions — deadlines on properly sealing a suspended well range from six months to 25 years in the United States.

When things go awry at an inactive well, there’s risk of explosion, soil and water contamination and release of air pollutants, according to Jodi McNeill, a policy analyst with The Pembina Institute. And then there are the emissions.

“When something hasn’t been plugged, it just continually releases greenhouse gases into the atmosphere,” McNeill said.

As long as the companies that hold the licences to these wells stay financially afloat and honour their cleanup obligations, this isn’t necessarily a significant risk to landowners, Bennett told The Narwhal.

One of his concerns is the implications of the Supreme Court’s upcoming decision on the Redwater case — due out this fall. If the lower court’s decision is upheld, it would allow the creditors of bankrupt companies to collect what they’re owed before any money is used for cleanup of the company’s liabilities.

In essence, the decision could make cleanup the last priority when distributing any funds a company might have left — a substantial concern for landowners waiting for wells on the property to be cleaned up, and a big potential bill for taxpayers.

The regulator, an appellant in the case, is similarly concerned, saying in February, “If this decision is upheld by the Supreme Court of Canada, we — and every other regulator in Canada — will no longer be able to hold companies accountable for cleaning up their mess.”

A gas well on the horizon. Since 2009, the Alberta government has given the Orphan Well Association more than $30 million in grants and moved to loan the organization $235 million in 2017. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

But critics worry that the regulator is already struggling to do just that.

Documents obtained by The National Observer revealed that a top official with the regulator estimated that cleanup of conventional oil and gas wells would cost the province at least $100 billion — a number, it noted, is “expected to grow.”

How that number got to be so big is of no surprise to people familiar with how the regulator works.

“The [regulator’s] system is not achieving anything,” said Keith Wilson, a lawyer who has been working on these sorts of cases for thirty years.

“If anything, it’s creating a false sense of comfort that this problem is being addressed — and we know it’s not.”

The huge price tag is due, in part, to the large number of wells in the province. A report from the C.D. Howe Institute estimates that there are roughly 450,000 wells in the province — a well for every 1.4 square kilometres in Alberta.

It’s estimated that at least a third, 155,000, of those wells are no longer producing, but have not been reclaimed, representing a financial liability for the company that owns them. If the company goes bankrupt, the cleanup responsibility is shouldered by the Orphan Well Association.

The Orphan Well Association brought in just $30 million from the orphan fund levy, collected from industry, in 2017. Since 2009, the Alberta government has given the Orphan Well Association more than $30 million in grants and moved to loan the organization $235 million in 2017.

The federal government has similarly siphoned public money to clean up after bankrupt companies. Last year, it announced it would allocate $30 million to efforts to clean up orphan wells in Alberta.

Last year, the industry-managed Orphan Well Association reported more than $30 million in total expenditures. In that year they abandoned (the term used to refer to plugging, or sealing, a well) just 232 wells.

In total, just over 600 orphan sites have obtained reclamation certificates over the years, meaning they have been sealed and the sites have been deemed to have been remediated.

There are more than 2,000 wells in the Orphan Well Association’s inventory that have not been sealed, and more than 1,100 that need to be reclaimed. (The Orphan Well Association did not respond to The Narwhal’s requests for an interview.)

An orphan well near Taber, Alberta. Bennett was surprised to find that the pressure on the well was still high. It has yet to be safely sealed. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

In theory, wells shouldn’t end up in the hands of financially unstable companies, because the permissions for and transfer of Alberta’s wells are regulated by the Alberta Energy Regulator, a corporation at arm’s length from government meant to oversee all energy projects in the province.

But, critics worry, the regulator’s system isn’t working.

There are two primary mechanisms the regulator uses to collect money from companies to fund cleanup of wells left behind by defunct operators.

The Orphan Well Levy is calculated by determining a company’s share of total industry liabilities, using a program called the Licensee Liability Rating. Money paid into this levy is used to fund the Orphan Well Association’s annual cleanup efforts.

The other mechanism is known as the Liability Management Rating system. In this system, a company’s assets (essentially an estimate of the money it makes from oil and gas production) are measured against its liabilities (the cost to seal and clean up all its infrastructure) to establish a ratio. If the company’s ratio of assets to liabilities is less than one — if it has more liabilities than assets — it must pay a security deposit to the regulator.

In theory, this system should ensure that financially unstable companies would have already paid a deposit to cover cleanup costs before ending up in the red.

Crucial to the calculation of a company’s assets is the company’s reported production in the previous year, multiplied by what’s known as the “industry netback,” which is essentially a measure of gross profit.

This could be a reasonable calculation of a company’s assets if updated regularly, but The Narwhal found the regulator still uses profitability numbers that haven’t been updated in nearly a decade.

Keith Wilson is adamant this is very problematic. “The [system] is supposed to be a responsible measure of the ratio of the company’s liabilities to their assets,” Wilson, the lawyer, told The Narwhal.

“It’s obvious to anyone who takes even the most superficial examination of the [regulator’s] program that it grossly overvalues the assets and equally grossly underestimates the liabilities.”

The result, he added, is “a rosy picture that has no bearing to the true risk to the taxpayer and to landowners.”

The landscape surrounding Huvenaars’ family farm is beautiful — and dotted with wellsites. There are 450,000 wells in Alberta, one for every 1.4 square kilometres. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

The land surrounding Ron Huvenaars’ farm. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

Alberta’s “industry netback” — the standardized measure of a company’s gross profit, used to calculate a company’s financial standing — was set in 2015, but the actual figures used in the calculation of the netback are based on data from 2008 to 2010, according to Melanie Veriotes, a spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator.

In essence, this means the regulator is calculating a company’s assets by using a measure taken from a time when oil prices reached nearly 150 USD per barrel and when natural gas prices followed a similar trend.

Oil prices declined after the 2008 global recession (and subsequently began to recover in 2010), but the average real monthly benchmark oil price (for WTI crude, commonly used as an industry benchmark) over the three years was still over 80 USD per barrel.

In contrast, the average real monthly oil price from 2015 to 2017 was significantly lower — at under 50 USD per barrel.

Oil prices are not explicitly included in the calculation of industry netback, but Veriotes confirmed that “oil prices indirectly influence the industry netback.”

“Oil prices are low today and have been for the last three years,” Lucija Muehlenbachs, an associate professor of economics at the University of Calgary, told The Narwhal by e-mail.

“If more recent data were used, this would make the industry netback much lower.”

Essentially, the Alberta Energy Regulator is allowing oil and gas companies to assume much higher profits than they currently receive — a practise the industry website Daily Oil Bulletin refers to as “providing some relief,” acknowledging that “a recalculation of this value using a more realistic netback would push many producers into negative… territory.”

Veriotes told The Narwhal that industry netbacks are updated “if the values have changed and as priorities allow.”

This doesn’t sit well with Regan Boychuk, a founder of Reclaim Alberta, a group advocating for the cleanup of inactive wells as a job creation program.

He is adamant that the netback was intended to be a regularly updated rolling average, as stated in the regulator’s own rules.

“The regulator has never updated the netback,” he told The Narwhal. “The three-year average has never rolled.”

“If industry had to pay even tiny deposits towards its cleanup obligations, many many companies would collapse,” he added.

“It is that far gone.”

Critics say the exaggeration of profits alone is a huge problem, one with big implications for the regulator’s ability to ensure industry cleans up its well sites.

For decades, landowners have argued that this is a crucial part of the social contract — that companies pay for the messes they make.

“As parents we teach our children that before they go to the next box of Lego, they need to clean up the last box of toys,” Wilson, the lawyer, told The Narwhal.

Why, he wondered, shouldn’t industry do the same?

The system’s flaws, critics say, mean it’s increasingly feasible that taxpayers will end up on the hook for a larger share of cleanup costs as more companies declare bankruptcy and the Orphan Well Association struggles to keep up.

And, as it turns out, the problem isn’t just that assets are exaggerated by the regulator.

There’s another important number: the liability estimate. This is the estimate of the total cost to fully seal off and clean up a company’s wells — and it’s essential to the regulator’s balance sheet.

The ratio of assets to liabilities is crucial to whether a company can take on new wells, whether it is required to pay a security deposit against the cost of cleanup and the amount it will have to pay into the orphan well fund.

Yet the regulator’s liabilities numbers, too, can be wildly off-base.

Cleanup costs are calculated based on the Alberta Energy Regulator’s estimates from 2015. These numbers have been criticized for failing to take into account variation in site condition and for being much lower than actual costs.

Ronald Thiessen, a researcher at the University of Calgary, has spent years analyzing available data on reclamation costs of Alberta’s wellsites. He found that cleanup costs for at least 60 per cent of wellsites exceed the regulator’s estimates.

According to Thiessen, one of the biggest contributors to cost is the amount of contaminated soil that must be dug up, loaded onto trucks and driven away. Salts present big challenges around wellsites, he said, and leaked oil and gas can also be a problem.

The regulator uses average cost estimates for reclamation to establish a company’s total liabilities, based on geographic area. The regulator’s estimates of the costs to clean up wellsites range from $16,500 in the grasslands to $42,125 in the high alpine; the average estimate across the seven geographical areas is $28,321.

Thiessen’s research, though, found that the median cost of cleaning up an orphan well in Alberta is nearly double the regulator’s estimates, at $53,000 per site.

He recommends the regulator raise its estimates of reclamation costs, which he acknowledges would mean a greater cost to companies in the former of the deposits they would need to pay.

“Taking an average and applying it to any given site is dangerous,” Thiessen told The Narwhal.

Jodi McNeill of the Pembina Institute agrees. “There are a lot of concerns about the formulaic way in which assets and liabilities are calculated,” she said. “Both the asset and liability side are not being representative of true site-based liabilities.”

Bennett and Narwhal journalist Sharon Riley visiting an orphan well near Taber, Alberta. Farmers must ensure their irrigation equipment will pass over wells like these. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

She’s also concerned that the regulator doesn’t take into account larger cleanup costs for the outliers — the sites with huge cleanup bills.

“[The system] can’t account for cases where a wellsite can have especially big problems,” she said. “We’ve seen wellsites that have a cost of $2 or $3 million to clean up.”

When The Narwhal asked Melanie Veriotes, a spokesperson for the regulator, if it planned to update its figures, she said by e-mail “regardless of which assessment tools we use, companies are responsible for the costs associated with cleaning these sites. None of these calculations change that fundamental premise.”

“We are working to update our liability management program,” Veriotes added, noting that the regulator is “reviewing our processes to better understand what is working well and what needs to change.”

Wilson, the lawyer, is adamant that the average cost to clean up a site is much higher than the regulator’s estimates — or Thiessen’s research.

“I get criticized by people in the industry when I say that the average reclamation cost is $300,000,” he told The Narwhal.

“They say, ‘you’re nuts, it’s way higher.’ ”

Thiessen agrees that the average cleanup cost could be much higher than what his research found, but, he noted, “a larger, more representative and publicly available dataset is required,” — something industry hasn’t released.

Wilson points out that even if the average cost to clean up a wellsite was $53,000, the total bill to clean up Alberta’s wells is still enormous.

He pulls out his calculator to do a quick estimate.

“Error!” he says, laughing when his calculator can’t compute the figure, “Error! The number’s just crazy big.”

Wilson was asked what was wrong with the regulator’s rating system at a conference earlier this year. His answer was clear.

“Everything.”

When asked how to fix the system, Wilson replied, simply, “get rid of it.”

Politically though, that’s tricky. “The current government is in a political competition with its nearest rival, the [United Conservative Party], as to who can project better a pro-industry image,” Wilson told The Narwhal.

Some worry that tweaks to the system could mean a financial disaster, pushing more companies to bankruptcy — and more wells on to the Orphan Well Association, which can’t afford to clean up its current inventory.

There’s also the possibility, according to Muehlenbachs, the economics professor that “fear for the industry [or] fear of what this says of the industry,” might stop the regulator from making any substantive changes.

The idea of propping up companies doesn’t sit well with landowners who have to live with the wells on their land.

And if the Redwater decisions stands, which many believe it will, Action Surface Rights worries it could incentivize companies to walk away from liabilities.

Bennett is worried that companies will “come in and milk the resource as much as they can and abscond with millions of dollars.”

“They privatize the profits and then they bugger off and socialize the losses.”

Journalist Sharon Riley discusses well liabilities with landowner Daryl Bennett in the Taber Tim Hortons. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

All of this leaves landowners like Ronald Huvenaars feeling vulnerable.

Huvenaars’ dad started a farm in 1964. For years, the family raised hogs, though these days they focus mostly on crops — renting out land for potatoes; producing seeds for Dupont. The land for the family’s farm, Pigs Fly Farms, is dotted with shelters for the bees that pollinate canola.

Huvenaars stands beside a derby car used by his kids. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

Huvenaars poses in front of silos on his family farm, Pigs Fly Farms, which produces seeds for Dupont. Photo: Theresa Tayler / The Narwhal

And then there are the wells. In 1985, an oil and gas company approached Huvenaars’ dad about drilling a well on the family farm. His dad agreed.

“It was kind of one of those things where it’s like well, they’re gonna do something anyways,” Huvenaars told The Narwhal, noting that the economy was tough at the time. “There was no money in farming and if you could create a little extra cash, it was enough to keep things going.”

But things have changed. Huvenaars says there’s no way he’d allow another well on his land without a fight.

Action Surface Rights is adamant that the inherent trust between landowners and industry is eroding — and concerned that the way the regulator is enforcing the rules don’t help matters.

But for Huvenaars, there’s little he can do when it comes to the two wells on his land, other than hope for the best. For many landowners, there’s a feeling of powerlessness when it comes to dealing with industry.

“It’s there,” Huvenaars said. “So what do you do?”