Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

According to Wet’suwet’en oral history, the Kweese War Trail is lined with the buried bodies of warriors who lost their lives avenging the murder of Chief Kweese’s wife and son.

The trail — a place where Wet’suwet’en youth can literally walk in the footsteps of their ancestors — branches out to important ancestral sites spread throughout the traditional territory of the nation’s five clans.

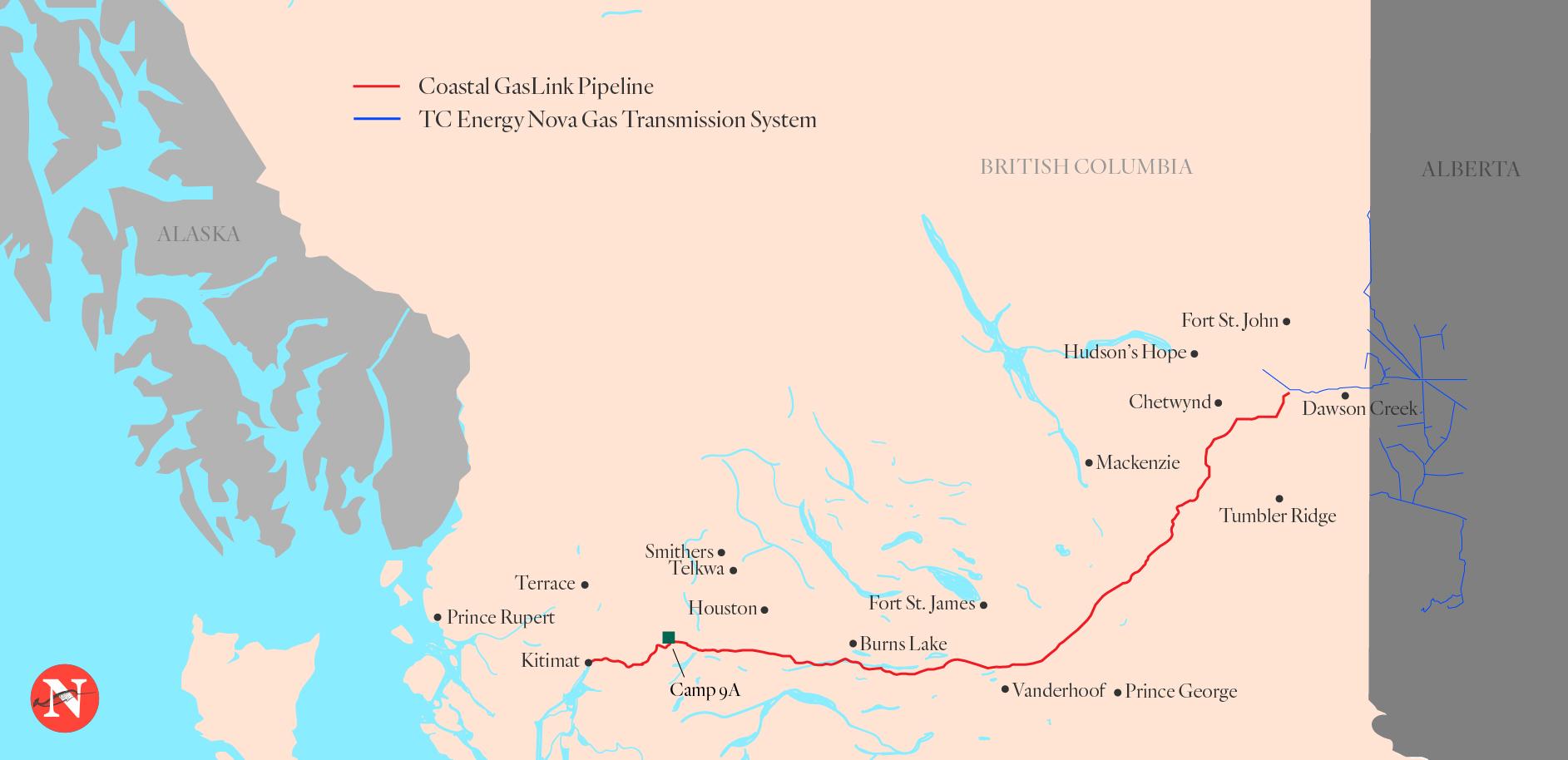

But now a 100-metre portion of the trail, a critical piece of history for the Wet’suwet’en and the origin of some of their clan crests, and another potential archaeological site lie buried under work camps and clearcuts for the $6.6 billion Coastal GasLink pipeline, proposed to move fracked gas from B.C.’s northeast to Kitimat to feed LNG Canada’s $18 billion liquified natural gas (LNG) export facility and the province’s promise of a LNG export boom.

On Jan. 4 the hereditary chiefs of the Wet’suwet’en issued an eviction notice to Coastal GasLink owned by TC Energy (formerly TransCanada), saying the company “bulldozed through our territories, destroyed our archaeological sites and occupied our land with industrial man-camps.” The eviction notice comes one year after the RCMP enforced a court injunction, forcibly removing and arresting Wet’suwet’en blockaders at a checkpoint designed to prevent the company from accessing work sites. That injunction was extended on Dec. 31, 2019, triggering the Wet’suwet’en eviction notice and raising the spectre of renewed tensions.

Although the B.C. government recently celebrated becoming the first jurisdiction in Canada to enshrine the rights of Indigenous people in its law, the Wet’suwet’en’s fight against the pipeline raises questions about Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination — in instances when permits have already been granted.

Mike Ridsdale, an environmental assessment coordinator for the Office of the Wet’suwet’en and a descendant of the first people to walk the trail, spent years carefully documenting important cultural sites along the historic path.

Tying up bright pink and blue ribbons, he marked trees bearing the telltale signs of cultural modification — folds of bark healed after strips were peeled away, harvested for household uses, kindling and markers for routes and trails.

In 2014, Ridsdale led provincial government and industry representatives along the trail, pointing out ribbons denoting a “Cultural Heritage Resource” or a “Culturally Modified Tree.”

Mike Ridsdale, environmental assessment coordinator for the Office of the Wet’suwet’en, near Telkwa, B.C. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Ridsdale, holding a form of culturally modified tree, near Telkwa. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Ridsdale hoped the markers would play a role in the trail’s protection, as advocated by Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs. But by the time he returned to the spot last August, the trees with pink and blue ribbons lay piled in the dirt along 100 metres of the Kweese War Trail that had been cleared for a section of pipeline.

“They are erasing our history,” Ridsdale tells The Narwhal, his silver hair peeking out from beneath his ball cap. “They’re erasing that part of our history that we know in this generation that may not be taught to the next generation.”

“Then it’s lost.”

Ridsdale in a stand of trees he flagged as culturally modified. Ridsdale tells The Narwhal he is worried Wet’suwet’en history is being lost with logged CMTs. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Culturally modified trees are considered important historic evidence of human occupation of the landscape. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Ridsdale re-flags a culturally modified tree. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

A felled culturally modified tree near Telkwa. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Historically modified trees are more than just a direct linkage to his ancestors, Ridsdale says. They are also critical to the Wet’suwet’en nation’s unresolved legal claim to its traditional territory.

For the Wet’suwet’en, it’s a conundrum: they need archaeological evidence to prove the legal boundaries of their Aboriginal title, yet they have no legal status to defend their cultural heritage from destruction.

“The thing is that I’m living this whole process [and] the process is broken,” Ridsdale says.

A newly cut and logged Coastal GasLink access road near Houston, B.C. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Chelsey Geralda Armstrong, a postdoctoral fellow in archaeology at the University of British Columbia, investigated the impact of the Coastal GasLink pipeline for the Wet’suwet’en and identified nine areas where construction permits lacked necessary archaeological impact assessments, which are used to determine if archaeological sites exist.

Armstrong sent a report to both B.C.’s Archaeology Branch, which manages archaeological resources protected under the Heritage Conservation Act, and Coastal GasLink. But she says they never responded.

Fieldwork conducted from 2013 to 2015 found the Coastal GasLink pipeline corridor rich in archaeological sites. A report submitted to provincial regulators in early 2016 found 85 archaeological sites, 65 of which are lithic, meaning they relate to stone or the presence of stone tools. An additional 14 sites were found to contain culturally modified trees and seven sites were considered cultural depressions — evidence of previous human occupation.

According to Armstrong, the trail itself is an archaeological site, potentially even a burial site — and is a key linkage point to other parts of Wet’suwet’en heritage.

“If you follow a trail, it will lead you to every single site on a landscape,” she says.

But the impacted area of the trail didn’t qualify for further archaeological investigations, according to a Coastal GasLink report and a portion of the trail was cleared.

“The site was just destroyed,” says Armstrong.

Coastal GasLink says it logged the area by hand, rather than bulldozing, and covered the trail with timber to avoid ground disturbance.

But some portions have been covered over by an access road, and if the trees aren’t replaced, Armstrong and others fear the trail will “brush over” and become unidentifiable. Ridsdale voiced concern that potential burial sites could be lost forever.

“Where else in Canada can you put a road over what could be a gravesite?” he says.

The archaeology branch eventually issued permits for an archaeological impact assessment — which allows for archaeological investigation like digging and boring into trees — for the impacted portion of the trail but only after clearing and construction had already taken place.

It was a decision that Armstrong had never seen before.

“So is it legal?” she asks aloud. “Sure.”

“Is it just? No.”

A map of the Coastal GasLink pipeline route and location of camp 9A. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Beginning in Jan. 2019 a Wet’suwet’en heritage site was bulldozed to make way for camp 9A, a Coastal GasLink work camp and staging area designed to house 450 workers that is now the subject of the hereditary chiefs’ eviction notice.

Wet’suwet’en elders knew the site had been a seasonal fishing village, so on Feb. 13, 2019, sent a small party to examine the site. The group says they discovered six projectile points on the upturned ground and gathered two as proof. They thought physical evidence in the form of these lithic stone tools would deter continued destruction of the site.

It didn’t.

Under B.C.’s Heritage Conservation Act, protected heritage sites can legally be destroyed as long as the provincial government issues a permit. Companies can apply for a permit to destroy, damage and/or move protected heritage objects and sites.

Coastal GasLink’s work camp 9A is designed to hold 450 workers. There are 14 such camps located along the length of the pipeline’s corridor. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

An RCMP outpost located along the service road that leads to the Unist’ot’en and Gidimt’en camps. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Coastal GasLink machinery on a mountain road in Wet’suwet’en territory. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The first step for industry is to hire archaeologists to file desktop reports that predict the potential for archaeological sites within the proposed project area. According to Coastal GasLink’s desktop report, the area where camp 9A stands was designated as having low potential for archeology sites. The report stated further ground investigations weren’t required but cautioned that “in the event that archaeological, historical or palaeontological resources are discovered, all work should be suspended immediately.”

The company also performed a preliminary assessment of the Kweese War Trail and did not identify any protected artifacts or trees. In July Coastal GasLink self-reported missing several archaeology impact assessment permits for multiple areas along the pipeline route adjacent to the trail.

Yet a 2007 report by Crossroads Cultural Resource Management, which utilized Wet’suwet’en traditional knowledge, found high potential for archeological sites in the entire area around both camp 9A and the Kweese War Trail.

Stone tools that members of the Wet’suwet’en reported finding at camp 9A. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Ridsdale walks in the forest near Telkwa, where his mother lived as a child before being removed to attend residential school at the age of seven. At one time, all the trees in the area would have been coniferous. Logging for fuel and construction material during the time of settlement in the area led to spruce and pine being replaced by alders and poplars. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Rick Budhwa, applied anthropologist and archaeologist and principal of Crossroads Cultural Resource Management, says these kinds of reports are interpretive, and different archeologists use different criteria, resulting in different declarations of potential. The legislation in the Heritage Act offers the most protection for sites considered unique, like petroglyphs, compared to trails and culturally modified trees, he says.

Budhwa adds that companies found breaking rules designed to protect heritage sites can be fined up to $1 million, but he is unaware of these fines ever being issued in B.C.

Areas identified as “high” or “medium” potential require an archaeological impact assessment. Although the area of camp 9A and the impacted section of the Kweese War Trail were both deemed low priority in Coastal GasLink’s desktop report, nearby areas were found to have higher potential.

Yet archaeologists hired by Coastal GasLink couldn’t proceed past Wet’suwet’en checkpoints to complete the required fieldwork in these areas.

The B.C. government issued construction permits anyway.

Coastal GasLink workers near Houston on Oct. 13, 2019. Amber Bracken

A red dress hanging from a road sign signifies Canada’s missing and murdered Indigenous women. The dress hangs along an access road being used by Coastal GasLink. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Workers monitor a section of narrow access road on Oct. 11, 2019. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

In an emailed statement to The Narwhal, the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission said it is “not uncommon” to grant permits before all necessary assessments are complete, because they can technically still be conducted prior to construction. The assessments in this instance could not be completed before the permits were issued “due to Unist’ot’en activities impacting the ability to conduct work,” the commission’s email stated.

In an email to The Narwhal, the archaeology branch said the trail has never been identified in any archeology assessments for the Coastal GasLink project submitted by the company.

But reports submitted by Coastal GasLink appear to ignore the findings of Crossroads Cultural Resource Management.

“I struggle to see how this wasn’t consulted. I struggle to see why it wasn’t consulted because it is a publicly available resource,” Budhwa says.

Budhwa says there are pressures on archaeologists working for industry, as compared to those who are conducting research, that can impact how potential archaeological sites are assessed.

“When you have a bulldozer behind you ready to impact land, you’re working on a strict timeline. You can’t be concerned with the finer scales of archeology,” he says.

A newly cut and logged Coastal GasLink access road on Oct. 13, 2019. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

After the incident, the Oil and Gas Commission released a bulletin stating the stone tools were likely not found in their original location.

Archaeology depends on layers of soil to date artifacts and to make extrapolations about the circumstances in which they were left, says archaeologist Chelsey Armstrong, who is a postdoctoral fellow with the Smithsonian Institution. “If it’s mixed up in soil that’s been disturbed, you’ve lost all that context. And so of course it’s not from its original location. They bulldozed it.”

Armstrong helped draft an open letter to the archaeology branch, calling for a complete archaeological impact assessment. More than 60 professionals signed the letter, but the government never responded.

Instead, the site was given “legacy” status meaning it was no longer protected because it had already been destroyed. Questions have since been raised about the legitimacy of the archaeological finds, but Budhwa says in a disturbed context it is impossible to know for sure.

“At this stage, there is no way of knowing how and when those artifacts got to their place. Regardless, it’s still considered an archaeological site,” he says. “In my opinion, what is more important than the found artifacts is that proper process is followed to manage for those artifacts and any additional archaeological sites.”

Last June, Coastal GasLink was reportedly three months behind schedule because of the Wet’suwet’en blockades.

“Delayed access has had an economic impact that is very difficult to estimate or quantify,” Coastal GasLink company spokesperson Suzanne Wilton said in an emailed statement.

Coastal GasLink disputes that any cultural values have been impacted on the trail, Wilton said, adding the company is back on track for the 2023 projected completion date.

Camp 9A where six lithic tools were reportedly found. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

In November, B.C. became the first Canadian province to pass legislation to implement the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People (UNDRIP), which says Indigenous peoples must give their “free, prior and informed consent” prior to resource development in their territories.

Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs have opposed the Coastal GasLink pipeline and others, including Chevron’s Pacific Trails and the Enbridge Northern Gateway pipelines, for years, Ridsdale points out.

Since 2010, hereditary chiefs and their supporters have maintained camps and checkpoints along a remote forest service road that provides access to the Coastal GasLink pipeline route, in order to assert jurisdiction and prevent clearing work permitted by the province but opposed under the Wet’suwet’en’s own customary law.

The checkpoints, a display of occupation on their traditional territory, began at the Unist’ot’en camp at the 66-kilometre mark on the forestry road. They then expanded to the Gidimt’en camp, 44 kilometres up the road, to Likhts’amisyu clan territory near Parrott Lakes, about 35 kilometres south of Houston and, most recently, to a new support camp 39 kilometres up the road.

Last January, in a violent clash, the RCMP removed the checkpoint gates and arrested 14 people under a court-ordered temporary injunction. Until then, the Wet’suwet’en had successfully prevented pipeline contractors and archaeologists employed by the company from accessing the site.

Indigenous rights, as defined by UNDRIP, were seriously infringed, when Wet’suwet’en members were arrested and removed from their territory, Ridsdale says. He is hopeful the new law will better protect heritage sites, but doubts change will come soon enough for the Wet’suwet’en.

A view of forest in Wet’suwet’en territory. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Though exact boundaries remain undefined, more than 22,000 square kilometres of Wet’suwet’en lands have never been ceded through treaty, as affirmed by the landmark 1997 Delgamuukw case. The case confirmed Aboriginal title exists in B.C. as a right to the land itself — not just the right to engage in traditional practices such as hunting and fishing — and said the government must consult with, and possibly compensate, First Nations when their rights are affected by decisions on Crown land. In the Delgamuukw title case, hereditary chiefs were recognized as the rightful representatives of the Wet’suwet’en and managers of territorial lands.

Coastal GasLink — like many companies doing business in the traditional territory of First Nations — signed agreements with band councils, elected in a process set out in Canada’s much criticized Indian Act to govern communities on reserves.

Ridsdale, who took part in an Environmental Assessment Office working group for the project, says relations with the company weren’t always so tense. Coastal GasLink funded the Wet’suwet’en office to engage in consultation efforts and shared data from preliminary studies, he says.

Through the working group, the Wet’suwet’en convinced the company to relocate a short section of pipeline. But Coastal GasLink rejected the nation’s proposal to reroute the pipeline to spare the trail.

The logged pipeline right-of-way near Houston, B.C., on Oct. 13, 2019. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

The Coastal GasLink pipeline regulatory review took six years and was supported by more than 7,000 pages of documentation. Archaeology requirements were just one component.

The process “is bloated, it’s huge, it’s complicated,” Budhwa says.

Consultation with First Nations for pipeline and other projects is required by law. Yet what constitutes adequate consultation is undefined, and the regulatory process makes it very difficult for First Nations to meaningfully voice their concerns, according to Budwha.

Responding to reviews for projects like the Coastal GasLink pipeline can be a significant burden for First Nations.

Wet’suwet’en member George Lenser walks through nation’s territory to check on construction. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

A logged pipeline right-of-way near Houston. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Lenser rides through his territory in October to monitor construction and clearing work for the pipeline. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

“You pile on a whole bunch of paperwork and reviews for projects and you put a strict timeline on it for them to respond to. And if they don’t respond within that timeline, the ship sails,” says Budhwa.

In an emailed statement, Coastal GasLink said it provides “opportunities for interested Indigenous groups to participate directly in heritage resource studies.”

Between January 2019 and Oct. 31, 2019, the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission conducted 56 inspections of the Coastal GasLink pipeline. The commission issued one warning letter and one order to stop work in an area where the company self-reported missing archaeological impact assessments.

An Office of the Wet’suwet’en request to Doug Donaldson, B.C.’s Minister of Forests, Lands and Natural Resource Operations, to halt clearing work at the cultural sites was deferred to the Oil and Gas Commission, which did not issue a stop work order.

An Aug. 2019 report published by the Canadian Centre For Policy Alternatives found the B.C. Oil and Gas Commission was established as a “one-stop” shop to streamline the industrial resource projects.

“From a very early state the OGC bore the hallmarks of a ‘captured’ agency,” the report states, and has led to a troubling “regulatory breakdown” when it comes to the protection of the environment and Indigenous rights.

It’s a view shared by supporters of the Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs.

“The whole system is built for oil and gas. It’s not built for Indigenous people and it’s definitely not built to protect these cultural resources,” says Anne Spice, a Tlingit woman who is a long time Unist’ot’en camp supporter and a PhD candidate in anthropology.

“It seems like the whole structure is set up to approve projects and to make sure that the projects are done quickly.”

Tlingit woman and PhD candidate in anthropology Anne Spice at the Gidimt’en checkpoint, near Houston, B.C., on Oct. 11, 2019. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Ridsdale is more worried than ever about preserving Wet’suwet’en cultural history.

“This one project is killing our history. It’s taking away the history that we want to teach our children,” he says, standing on the outskirts of a former village site near what is now Telkwa.

Ridsdale has changed out of his “town-shoes” into heavy-duty rubber boots to give a tour of culturally modified trees. He begins by talking about how his people used the area but the story abruptly turns very personal.

His mother lived at Telkwa when, at the age of seven, she was taken to Lejac Residential School, more than 200 kilometres away. As a native Wet’suwet’en speaker, she was whipped for not knowing English, or not learning it fast enough.

Art decorates the window at the Unist’ot’en healing centre near Houston. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

Ridsdale in the forest near Telkwa where his mother lived as a child. Photo: Amber Bracken / The Narwhal

In the middle of winter, she escaped with her two sisters, then aged five and nine, wearing only the dresses and shoes provided by the residential school. They survived by following the train tracks and with traditional knowledge imparted from their families. When they finally made it home, an Indian agent was waiting to take them back to residential school.

Ridsdale, like many Wet’suwet’en, is not fluent in his own language. His mother did not live to hear the apologies of church and government.

Ridsdale worries it will be the same with his people’s cultural history — that everything will be gone by the time the apologies come. As with residential schools, “it’s easier to say sorry than to ask for permission,” he says.

“Give us our land back,” he says. “Let us work with you, with our governance system, with our laws. Let us work together.”

With files from Carol Linnitt.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...