A deadly disease is killing millions of bats. Now Trump funding cuts threaten a promising Canadian treatment

At a crucial point in their research, biologists are scrambling to find new support for...

The worn peaks of the Torngat Mountains slope into rubble before crumbling into the Labrador Sea. They dip into verdant valleys and shallow bowls perched thousands of metres into the sky. The peaks grow taller as you travel north, replaced by straight-blade ridges and jagged tops. Trees peter out of the subarctic landscape long before you reach them, but low brush and willow, fireweed and berries crawl across their shores and climb as far as they can find soil. These stoic tortoises and feisty razorbacks proffer adventure to those who seek it, but perhaps they’re more interested in telling you a story — if you’ll listen.

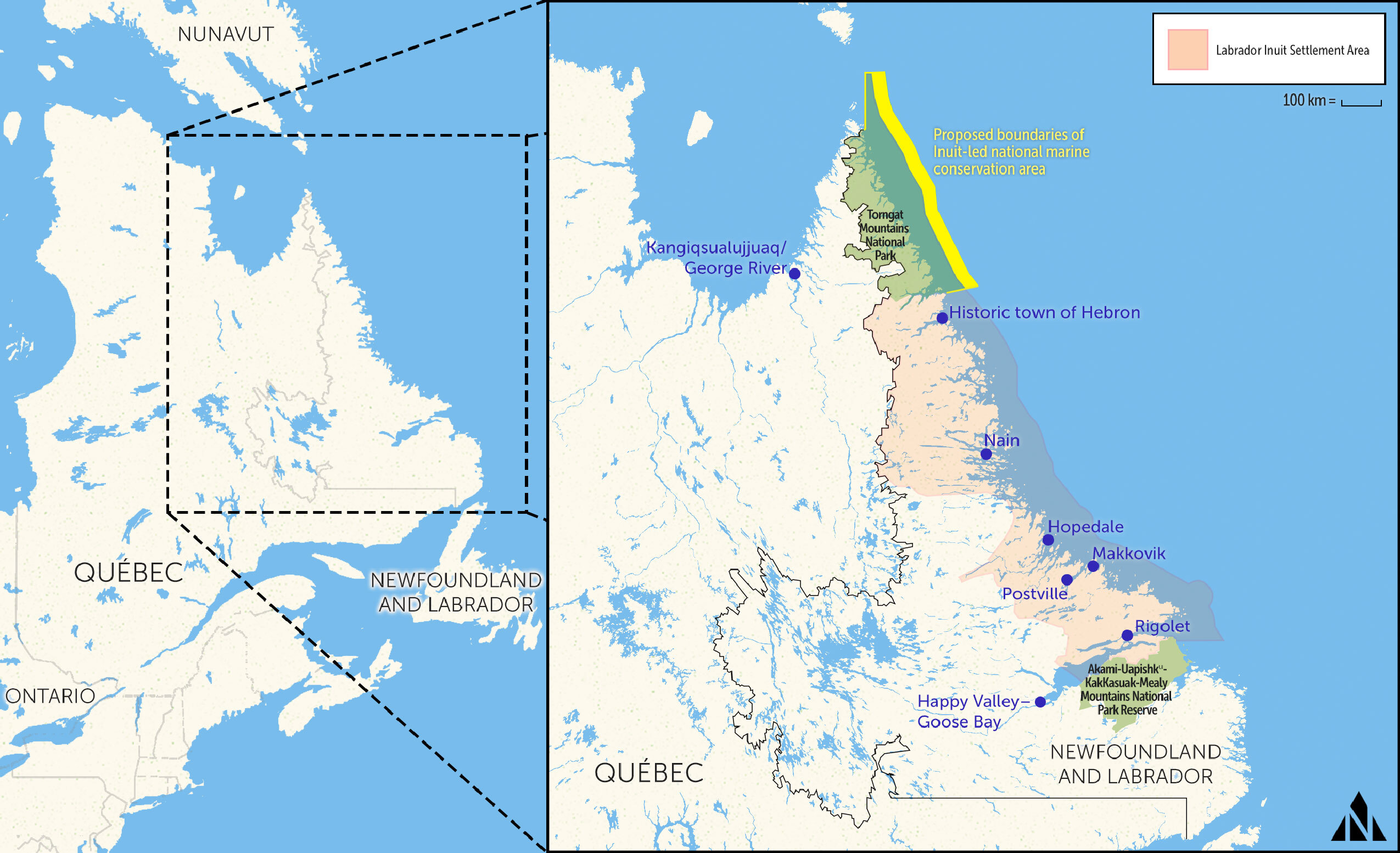

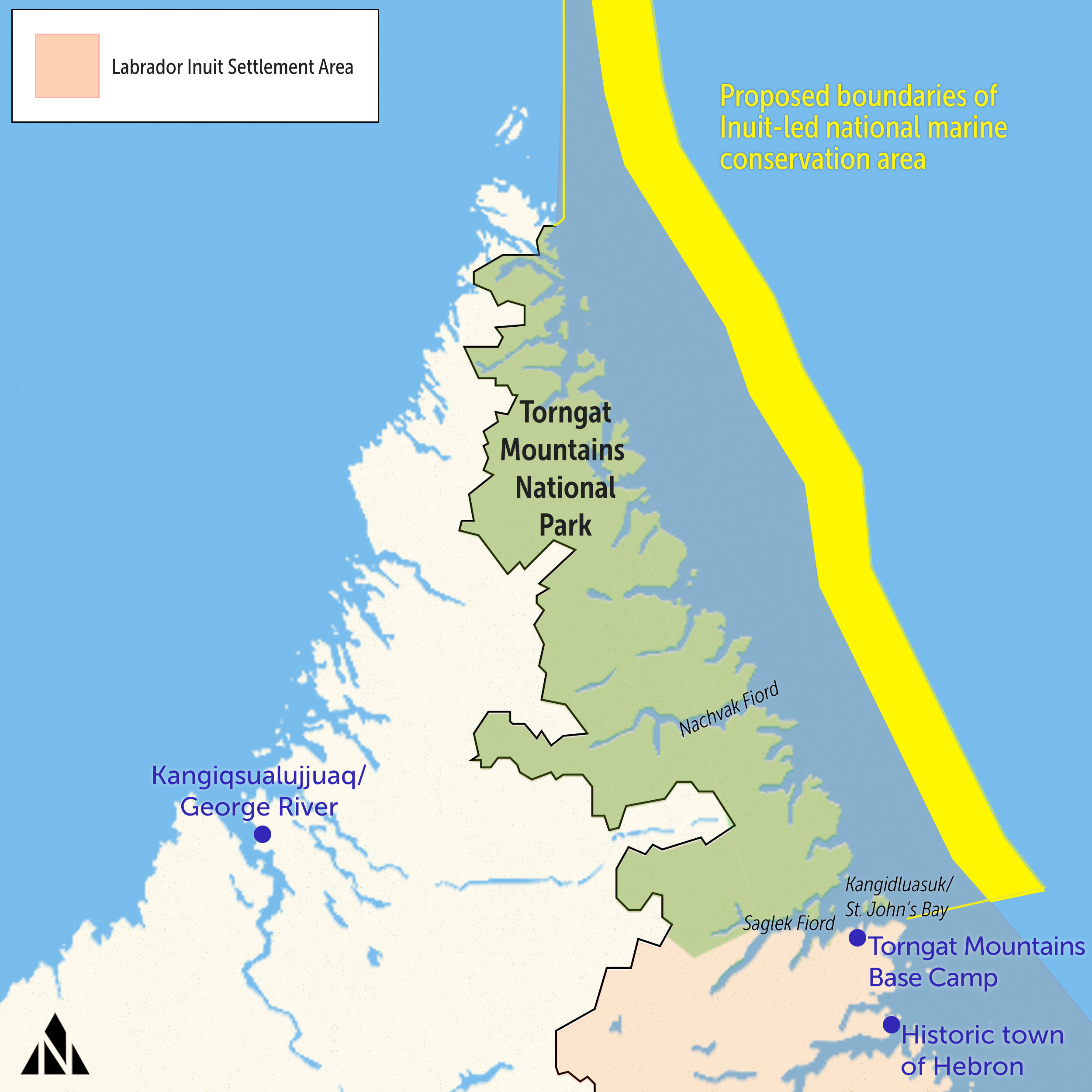

Torngait, in the Inuttitut dialect, means “place of spirits.” It’s from this word that the Torngat Mountains derive their name and from the Inuit that they derive their protection. In 2005, the Labrador Inuit Association and the governments of Canada and Newfoundland and Labrador signed the Labrador Inuit Land Claim Agreement. It established the Torngat Mountains National Park Reserve — the precursor to the national park that followed in 2008.

Unlike those before it, Torngat Mountains National Park was co-led by the Indigenous people of these lands, rather than imposed on them. The Labrador Inuit Association’s chief negotiator, Toby Andersen, said at the time that the park reserve was “the Inuit gift to the people of Canada”: a place where cultural heritage and natural beauty can be both protected and appreciated. All 9,700 square kilometres of land, right up to the low-water mark. While several of Canada’s national parks attract millions of visitors annually, just 489 people visited the Torngats this past summer — making it one of the most beautiful places on Earth that few people will see with their own eyes.

Now, almost two decades after the park was established, work is underway to protect the waters that pool at the feet of those mountains and stretch into the Labrador Sea, shuttling icebergs and boats alike. The proposed borders of this first Inuit-led national marine conservation area stretch around these subarctic waters where coral gardens flourish, offshore oil and gas is largely untapped and the dynamic sea ice choreographs a food chain that sustains seabirds, fish, whales and people.

But to protect these fragile waters, they also need to be understood. A massive initiative is underway to braid together generations of Inuit Knowledge with cutting-edge technology into a comprehensive portrait of what is known and still unknown about these nearly 15,000 square kilometres of marine area off the coast of Torngat Mountains National Park.

Unrestricted by boundaries or a specific moment in time, this is a story about that place and what it means to protect it.

Before reaching the Torngat Mountains, the northern extent of Labrador that thins to an arrowhead pointed at Baffin Island, we first had to get to Nain. The largest and northernmost community in the northern Labrador region of Nunatsiavut, it’s still some 300 kilometres south of the Torngats. I spent a day driving and then flying, first from Toronto to Halifax and then on to Happy Valley-Goose Bay, Labrador. For photojournalist Patrick Kane, who travelled from Yellowknife, it took two days, and twice as many stops. We met around dinnertime in Goose Bay on July 18, in the unexpected 30-C heat, and flew out first thing the next morning to Nain in a tiny Twin Otter plane.

Founded more than 250 years ago in the cusp of Unity Bay, Nain is home to nearly half of the 2,600 residents of Nunatsiavut, 90 per cent of whom are Inuit. The communities aren’t connected by road, but planes alight tiny airstrips that punctuate the Labrador coast, and a ferry runs from Goose Bay up to Nain, stopping at each community in between. It leaves Goose Bay on Sundays and arrives in Nain on Wednesdays, as long as the water is open. Nunatsiavut, a region roughly the size of Scotland, includes 49,000 square kilometres of coastal waters that remain unprotected — for now.

Nunatsiavut is one of four regions that comprise Inuit Nunangat, the Inuit homeland in Canada, which also spans the Beaufort Delta in the Northwest Territories, Nunavut and Nunavik in northern Quebec. Together, Inuit Nunangat encompasses 40 per cent of the land and 72 per cent of the coastline in Canada.

Nain’s sandy airstrip hugs the shoreline of Unity Bay and as Kane and I step off the plane, we can see CCGS Amundsen anchored in its waters. The red-and-white ship is nearly 100 metres long — think a track-and-field sprint — and carries a helicopter on board, as well as 12 scientific laboratories and bunks for about 40 researchers and 40 mariners. Named for the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, the Canadian Coast Guard icebreaker is fitted with high-tech equipment for marine research in Arctic environments. Every summer it leaves its port in Quebec City to take on various projects along Canada’s northern coastlines, from wildlife studies and oceanographic data collection, to measuring how atmospheric pollution is stored in the marine environment and whether a warming climate risks its release.

But this current research mission is unique, because for the first time its agenda has been set by an Inuit government. Michelle Saunders, the research manager for the Nunatsiavut Government, spent a leg onboard the Amundsen last year, and wrote the application for ship time this season. “I came back and I said, ‘Psshh, we could do that,’ ” she laughs.

Today, Saunders is driving around in a forest-green pickup truck, shuttling Nain residents between the town and the barge that will carry them to and from the Amundsen, as part of an inaugural “community science day.”

Saunders engaged the Amundsen to help her government answer some important questions about the waters at their shore. They needed data, Saunders says, “but I think that was going to happen with or without us.” Fisheries and Oceans Canada has their own priorities for study, some that fit with those of the Nunatsiavut Government, and her team would have some say in which projects go ahead. “But I think this is like a different level of decision-making,” she says. Setting the agenda provides more opportunity for the community to be involved and for their concerns and priorities to direct the studies.

In 2016, the Nunatsiavut Government began the work of developing a marine plan, titled Imappivut — “our oceans” in Inuttitut. The plan will guide the use of all of the waters at its shore — including those off the Torngats — for years to come. To begin this work, the government asked a question of community members up and down the Nunatsiavut coast: what does the marine environment mean to you? “The general theme was ‘it’s all connected,’ ” Saunders tells me, summarizing the responses they heard.

“You can’t talk about the marine environment without talking about the land, right? Or you can’t talk about the marine environment without talking about caribou, which doesn’t seem like an obvious connection, but they use the sea ice as well, and they go down and lick the salt off of the rocks, right? Eat the seaweed, right? So, it’s all a part of each other.”

When Saunders was studying ecology and conservation at Memorial University in St. John’s, the way her professors described the environment didn’t line up with that understanding. And there was no talk of humans and their role in that ecosystem, not even in the context of Newfoundland and Labrador, where Inuit, Innu and Mi’kmaq people have lived for thousands of years. To Saunders, an Inuk who grew up in Happy Valley-Goose Bay, this omission felt wrong. “We are a part of the environment. We are also animals,” she says, laughing at how obvious yet overlooked that sentiment is. “So I found that really confusing, discouraging and I didn’t enjoy my time in undergrad at all. But I think it made me want to do more because I was like, this is not how it should be.”

With her laptop open on the board-room table at the research centre in Nain, Saunders shows us some of the results from one of her current projects, tracking willow ptarmigan — or partridges — in the Torngat Mountains and farther south near the historic town of Hebron. The little brown birds wear tiny backpacks to log their movements — which are wide-ranging for the females, but lesser so for males. The study is meant to learn more about their breeding grounds and how they’re being impacted by climate change. Various birds and their eggs are an important food source along the Nunatsiavut coast.

Earlier this year, the government put out a notice warning of oil contaminants in the water near the community of Postville due to a diesel spill in 2020. That led to limitations on the amount of eggs people consume from three shorebirds: great black-backed gulls, common eider ducks and black guillemots.

In the Torngats, there’s no spill equipment, despite the recent increase in ship traffic, says Isabella Pain, the deputy minister of the Nunatsiavut Secretariat with the Nunatsiavut Government. Should the area become protected, there could be discussions around dedicated shipping lanes and proper monitoring and spill response.

Pain was at the table for the negotiations that turned the lands in this region into a national park and set the stage for a marine conservation area. “It was always important to protect our marine environment,” she says. “We depend on the marine environment for food, for travel for cultural reasons, for mental health, physical health: we rely on the ocean.”

Right now, Canada has five national marine conservation areas, as well as other areas listed for some level of federal protection under different departments, such as marine protected areas through Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

The federal government has an oft-repeated goal of protecting 25 per cent of land and water by 2025 and 30 per cent by 2030. As part of that, Parks Canada has committed to establishing 10 new national marine conservation areas by 2025, says Sigrid Kuehnemund, manager of national marine conservation area establishment in the Atlantic with Parks Canada — the Torngats marine area is one of them.

The abundance of life in these waters is one of the reasons the area is seen as an ideal candidate for protection. The Torngats area is a transition zone between Arctic and Atlantic habitats, Kuehnemund explains. “You have, you know, highly scenic fiords and long stretches of coastline and mudflats,” she says. “There’s a variety of marine mammal species that use the area and it’s important for concentrations of breeding and migrating seabirds and waterfowl.”

Ringed seals, narwhals and minke whales also use the area, and Eastern Hudson Bay beluga whales overwinter and migrate through these waters. This subspecies of beluga is listed as threatened by the federal government as a result of commercial overfishing in the 19th century. They’re an important species for harvesting in Nunavik — though only in limited numbers, in order to sustain the population.

The value of these waters doesn’t end with Nunatsiavut.

Not all ships warrant their own line of swag, but a small table is set up at the Unity Bay dock with hats, stickers and magnets bearing the Amundsen’s decals. I take a few stickers and a cap for my ship-loving nephew as a man and woman in blue plastic smocks walk down on their break from the fish plant to pick up keepsakes. Trumpeters welcome the barge in, in an homage to the missionaries that landed here more than 250 years ago, and a crowd of about a dozen people is waiting at the end of the dock to board. When it’s our turn to climb aboard the barge, a woman sitting next to me tells me she’s been on the Amundsen only once before, when it was used as a floating clinic to carry out a health survey in Nunatsiavut.

Today, everyone from young children to Elders in the community are welcome to meet some of the scientists at work and the crew that keeps the ship running.

As well as giving community members a look at what happens on board, Saunders’ hope for the community science day was for the scientists to meet the people who they’re doing this work for. “Numbers on a page doesn’t do it for me, you know?” she says. “There has to be a reason why you’re doing it. We don’t do research for the sake of research. We do research for the sake of Nunatsiavut, right? For people. Otherwise, what’s the point of it?”

We disembark from the barge onto a metal staircase lining the hull of the Amundsen, where a lineup of crew members looks down at us and we look down at the waters of Unity Bay. There are massive, precise scientific instruments on board, a million-dollar remotely operated vehicle and more rudimentary tools, like screens for sifting through mud samples, which could have been borrowed from 19th-century gold panners. But all of this will help transcribe the story of the aquatic environment in Nunatsiavut, much of which remains unwritten.

On the Amundsen, Rodd Laing wears a jacket emblazoned with “chief scientist” on the back — a title he shares with David Côté of Fisheries and Oceans Canada. The director of environment for the Nunatsiavut Government, Laing has lived in Nain since 2012, but he boarded the Amundsen in St. John’s a week ago. After hosting the community event — and quickly watering his plants — he’ll travel the length of Nunatsiavut’s coast, past the mouth of Hudson Strait and the entrance to the Northwest Passage, to finally disembark in Iqaluit.

The subject of change is top of mind here, Laing says, a theme that dominates the questions he is receiving from community members lately, “whether it’s climate change, or they’re seeing new species or other things.” That’s partly why it’s so important to gather data now.

Along the coast, data is lacking, save for the understanding of the land and waters among the people who live here. “There is baseline information within Inuit Knowledge because that information is passed on for generations,” he says. “But the scientific baseline is really poor in a lot of areas, and so in order to understand change, you need a combination of this information.”

Volunteers from our tour group take turns emptying out water samples, hold core samples from the seafloor up close and watch in awe as a Greenland shark toys with a baited camera on the screens in the viewing room on the ship’s lower deck.

The work done on board the Amundsen is helping to fill some of the baseline gaps in scientific information. Even data on the depths of the waters off the northern coast, Saunders tells me, is severely lacking: “Nautical charts? Don’t trust them.” And she spends a lot of time on boats. Using the Amundsen’s multibeam system, she says, they’re starting to better understand what’s down there — like a 60-storey-high wall of corals and sponges in the ocean outside the community of Makkovik, halfway between Goose Bay and Nain.

In 2021, working off a tip from fisherman Joey Angnatok, the Amundsen’s remotely operated vehicle filmed the flourishing wall, called the Makkovik Hanging Gardens, with its pink, polyp-covered trees of paragorgia, known as bubblegum coral, and primnoa, or popcorn coral, extending orangey-beige fingers.

These corals can live for hundreds of years and form a habitat for deep-sea creatures, Vonda Hayes, a marine biologist with Fisheries and Oceans Canada, explains as the science day events wind down at the community hall in the evening. Dried corals are laid out on the table in front of her. This year, they found a second hanging garden near Makkovik.

Makkovik is far south of the Torngats but, Saunders says, it’s an example of how much is still unknown about Nunatsiavut waters. And it’s a reason why protecting the area, as mysterious as it is, is critical.

Laing and I take a seat at a picnic table outside the community hall. The sun is hesitating to set by 8 p.m. and flies are predating bare skin, which is more abundant than in years past. Average temperatures for late July fall in the mid-teens, but during our visit the temperature hovers between 20 C and 25 C. A lot of people in Nain comment on it.

As part of their work on Imappivut, the Nunatsiavut Government is carrying out a knowledge study, which involves gathering information from the people who know this land best.

It will also form a part of a 15-chapter research document Laing, Saunders and about 60 other people are putting together as part of the feasibility study for the Inuit-led national marine conservation area — currently dubbed the Torngats Area of Interest. The purpose is to gather all of the information both from western and Inuit Knowledge systems, and to identify any gaps in that understanding of the marine ecosystem beyond the coast of the Torngat Mountains. The two knowledge systems are considered equal. If, for example, western research shows a certain habitat map for char and the Inuit Knowledge study shows an additional area, the feasibility assessment will include both, Laing explains. And climate change is a consideration in every chapter, he adds: what they know now and what the potential implications of climate change could be. “Which is really important because that allows for some forward thinking and planning on that,” he says.

So far, there hasn’t been a lot of information gathered from people who know the Torngats area, Saunders tells me. “So that’s something that we’re targeting now: people who use this area regularly or used it in the past.”

The area has been used for thousands of years by Inuit who moved between camps with the seasons and animal migrations, rather than staying in a single place. But there is a darker, more recent history of people being relocated from settlements near the Torngats. Between the late 1700s and early 1900s many Inuit settled among eight sites established by Protestant Moravian missionaries along the Labrador coast. Some, like Nain, are still inhabited, while others were forcibly closed by the Government of Newfoundland and Labrador in the 1950s. One of them, Hebron, falls just south of what’s now Torngat Mountains National Park. In 1959, officials with the government attended a church service in Hebron to announce the remote community would be closed. Residents were relocated that week to various communities, with devastating consequences for many Inuit who struggled to adjust to a new place, away from friends, family and familiar terrain.

It made the Torngats less accessible, Pain of Nunatsiavut Secretariat says. The closest community to the Torngats became Nain. “It was hard to get back up there, but we’re seeing a real resurgence of people being able to use the area, getting access to the area by boat and by going up over the land on Ski-Doo in the wintertime,” she says.

The process of gathering information from the people who do know this area so well, Saunders says, is really a conversation: where they go, what routes they take and if they have camps or cabins here. It means asking people exactly what they’re seeing.

In the community hall in Nain, tables and posters display some of the work being done on board the Amundsen. There’s dinner and dessert, throat singing and a performance of “Sons of Labrador,” as well as an ode to the Amundsen’s captain. After the event wraps up, Saunders tells me, she texted Laing to say, “That was the best thing we’ve ever done.”

Because Inuit have co-led the Torngats proposal from the beginning, it has a dual designation as a national marine conservation area and an Indigenous Protected and Conserved Area — and in this way, it’s the first of its kind.

Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas are defined by three essential components: being Indigenous led, having a long-term commitment to conservation and elevating Indigenous Rights and responsibilities. Only three have been recognized as established by the federal government. But outside of federal legislation, several communities have declared protected and conserved areas under their own laws.

Torngat Mountains National Park predates the Crown government’s recognition of Indigenous Protected and Conserved Areas. Its unique partnership between Parks Canada and the Labrador Inuit resulted from their land claims agreement. The agreement also established self-governing powers under the newly formed Nunatsiavut Government, and created a new model for conservation that centres Indigenous use of the land. Developing Imappivut, Nunatsiavut’s marine plan, will see the ocean management chapter of the land claim fully implemented.

The Nunatsiavut Government’s decision to create an Inuit-led national marine conservation area, alongside Parks Canada, wasn’t without thought to forging ahead on their own. But, Pain explains, there is no mechanism under current regulations to create an Indigenous-led marine protected or conserved area that is recognized by the Crown, without partnering with a federal department. “It does have to be tied to some piece of legislation or regulation as it is,” she says.

“So that is sort of why we do keep referring to it as an Inuit-protected area,” Pain says. “We were the ones who developed this plan. As Inuit, we went to the government to say we want to have a protected area.”

The Nunatsiavut Government also recognized the benefits of the Crown’s partnership, particularly in terms of funding arrangements for activities within the area. “We’re not there yet,” Pain says, “but part of our thinking is once we have this protected area, we want Inuit to be on the land, on the ocean to monitor, to be guardians of that land. And so you know, along with a protected area, we hope to and we plan to negotiate funding for some of those things.”

From Parks Canada’s perspective, that ongoing monitoring and sustainable economy built around the conservation area is a part of their vision. “When a site is established, there’s really a long-term commitment by Parks Canada for research and monitoring,” Kuehnemund with Parks Canada says. It’s an opportunity for developing a conservation economy, putting permanent staff and infrastructure at that site and supporting coastal communities in developing ecologically sustainable businesses.

How that plays out, Kuehnemund says, is by allowing for a range of sustainable activities within different zones of that protected area — some that are strictly limited and others that allow for greater use. “Our process is very collaborative, and there’s a lot of engagement and consultation that happens in advance of deciding to establish the national marine conservation area,” she says.

The ability to someday establish a Crown-recognized and Indigenous-led marine conservation area, without it being tied to federal legislation, is an ongoing conversation, Pain says.

For Keith Watt, the Torngat Fish Producers Co-op’s general manager, it’s the partnership with Parks Canada that makes him apprehensive about the plan to protect the Torngat waters. He sees it as a method of hitting conservation targets — something the federal department is unequivocal about, though as a positive rather than a negative.

But for the Nunatsiavut Government’s part and the project in general, he says, “I think it’ll probably be a good thing in the long run, as long as consultation is done properly, as long as there’s not a lot of restriction.”

The co-op operates the Arctic char plant in Nain, which is supplied by 13 fishermen and employs another 30. It’s owned by the Nunatsiavut Government and leased by the co-op, which also operates a plant in Makkovik for crab, turbot and scallop. “There’s nothing wrong with fishing,” Watt tells me, adding that the co-op fishes a lot less than they used to and limits themselves to maintain the stocks.

Commercial fishing is allowed in national marine conservation areas, but bottom-trawlers, which the co-op uses for scallop and shrimp, are not. “I understand that but don’t support it,” Watts says, adding the proposed conservation area boundary is near what he calls one of the most important shrimp fishing areas, just off Cape Chidley, at the northern tip of the park.

Harvesting rights for Inuit beneficiaries, however, will not be affected if an Inuit-led marine conservation area is established. That’s a critical point. And the fish co-op is just one of many groups who are being consulted as the marine conservation project takes shape, along with the organization that represents Nunavik Inuit. The feasibility report coming out of all this work should be completed in 2024, Pain says, and then the discussions around finalizing borders, uses and a benefit agreement can take place.

In the future, she says, they will look at where else protected areas could be established in Nunatsiavut waters, through Imappivut. But first, the Torngats.

Watching the rocky landscape spread out underneath the single-engine prop plane, you can imagine the Laurentide ice sheet that lay here, and then melted away, leaving unevenly depressed ground where water pools. While the kilometres-thick mass of ice started shrinking away some 20,000 years ago, it was relatively late to leave Nunatsiavut — about 9,000 years ago.

As a result, these lands are still stretching upwards, shrugging off that weight, explains Robert Way, an assistant professor in geography and planning at Queen’s University who is from Labrador and studies the effects of climate change on northern environments. While much of the country and world experiences coastlines sinking into the ocean, these shores are still on the rise. (Though the sea level is expected to catch up at some point, it’s hard to say when exactly; many factors affect sea level rise and these shorelines are poorly mapped — a common theme in northern Labrador, Way adds.)

We set down in Saglek Fiord on a paved airstrip lined with rundown hangars — a strange sight in such a remote location. Its existence is a relic of the Cold War, built by the U.S. military along with a radar station in the 1950s to watch for a Soviet attack on North America. From here, it’s a few minutes in a helicopter to the Torngat Mountains Base Camp, a collection of about 50 buildings, wall-tents and domes just outside the southern border of Torngat Mountains National Park.

For the first hour after we arrive, every other person we encounter mentions a “bear situation” to Saunders. A polar bear was found dead on the shore of Kangidluasuk, or St. John’s Bay, just over from base camp, and she needs to take its head off. The Nunatsiavut Government requires samples from polar bears that die of natural causes or are killed in self-defence. Along with its head, Saunders takes fat and muscle samples to study its diet, age and general health indicators. It was a skinny young female, she tells us later. Another polar bear, large and agile, swam handily across the bay below the helicopter as we flew from the airstrip into base camp. It would be the first of more than a dozen polar bears we’d see that week — alive.

After dealing with the polar bear, Saunders started looking for Arctic char. Another one of her current projects is a sampling program to study the health of the char, a source of food and income in Nunatsiavut. She needed 30 fish from base camp and 30 each from two other locations within the park. A group of 18- to 30-year-olds visiting base camp as part of the Nunatsiavut Government’s Youth Leadership Program make quick work of gathering subjects for her, casting line after line into waters flush with fish.

Saunders, with the help of Parks Canada staff, handily prepares char for pitsiq — hashing fillets into small squares and hanging them out to dry — and collects their samples. If they’re interested, Saunders shows youth how she removes the digestive tract, tissue, a fin clip, an eyeball and the otolith – a tiny, solid ear bone, swimming in a sea of brains if the fish was bonked.

As well as being among the most enthusiastic anglers at base camp, the youth group hike, craft and talk. “You talk about all of the hard, difficult things that our relatives had to go through,” Megan Dicker, the program co-ordinator, tells me. “But it’s not only that. We talked about how skilled and how smart Inuit are, and how we were able to live the way we do in the North, so well, because we’re so expert.”

Like eating seal for the nutrients it provides and how it instantly warms you, she says, sliding an image of a seal dissection across the table in the base camp dining room; there are spaces to label the seal’s anatomy in Inuttitut. “And then in turn, we really respect it and use it for as many parts of it as we can,” she says. “Everything is connected in one way or another. And I think that really came through when we were here. Everything is reciprocal.”

Members of her group bustle in and out of the dining room, preparing their lunches before loading onto helicopters to fly out to Nachvak Fiord, about 100 kilometres north. As soon as the helicopter pilot drops Kane and I off in Nachvak, he starts shuttling groups that flew in earlier back to base camp, five people at a time. You would barely know that mountains rise up from the rocky shore or that they’re much, much higher than the ones surrounding base camp, because the clouds are sinking so low.

The youth fish for more char and help Saunders fillet and take samples as the fog settles in.

Only an hour later, as I climb into the helicopter to head back to base camp — the day cut short due to the weather — the pilot pulls out a yellow briefcase. It’s an emergency kit in case the fog is too heavy and he can’t make it back to the fiord for the last group, which includes two Parks Canada staff, Saunders, Kane and a bear guard with a three-barrel shotgun.

The mosquitoes were relentless, Kane tells me later, and it was hard not to think about the mother polar bear curled up with two cubs we’d flown over on the way in.

There was a palpable sense of relief, he says, when the pilot appeared through the clouds, singing David Bowie’s “Space Oddity” over the radio: “Ground control to Major Tom.”

That night at base camp, Saunders’ small crew is up processing the pink-fleshed fish well past 10 p.m. as evening anglers continue to pull them in.

Under a dark, cloudy sky, light and music and the smell of fish fill the research station, down the hall from the dining area and kitchen. While the scent of fresh char doesn’t seem to offend anyone, the cooks are quick to call out when the research station refrigerator is opened, releasing the breathtaking smell of rot from the polar bear head inside.

Andrew Andersen has been working in Torngat Mountains National Park since 2009, just one year after it was established. His father’s family comes from just south of the park.

“Going out on the land, I grew up doing it with my father’s side of the family: fishing and hunting, everything we could,” he says. “Now I do it with my family. We eat mostly wild food in our house: seal, geese, fish, caribou when we can get it.” In his lifetime, he’s seen the environment changing in the mountains and back home in Nain.

He remembers skating before Halloween in the 1990s, lacing up on the freshwater ice around Nain in October, and watching the sea ice forming by November. Since the turn of the century, all bets are off.

“It’s pretty much the talk of the town when we’re waiting for the sea ice to form,” Andersen says. Looking down the road, he says, people are asking the inevitable question: “Is there going to be any ice in 20 to 30 years?”

This year, it wasn’t until mid-January that the sea ice formed. There were some normal cold days and then two weeks above zero where the freshwater brooks burst open and flooded. The snow on the sea ice melted. After a few days back to cold temperatures, he says, the ocean was like a skating rink.

“There was no snow, so it was hard for ringed seals to build a home for their pups,” he says, which alarmed the hunters who rely on the ringed seals to feed the community. The shrinking season for sea ice has other consequences for Inuit, who rely on it to travel around the region, and for wildlife. Around base camp, more than a few people note the lack of sea ice is pushing polar bears closer to camp as they lose their hunting grounds.

In her role as the community climate change liaison for the Nunatsiavut Government, Chaim Andersen (Andrew’s cousin), ensures Labrador Inuit priorities and values are represented in programming through Environment and Climate Change Canada: both its Climate Change Preparedness in the North program and Indigenous Community-based Climate Monitoring, which gathers data on these changes in the marine environment.

Ice is considered a part of the infrastructure here and the changing nature of it is the biggest priority on her docket.

“It’s so integral to our communities in terms of travel and access to cultural and culturally significant places. I always say that ice is one of my best friends because it’s so important,” she says. “And there’s been a lot of uncertainty and vulnerability increasing in terms of, like, the length of the ice season, the predictability of the ice to whether the ice is safe or not.”

There’s also been significant greening on the land: brush that used to stop closer to the shore now climbs up the hills. Some suspect a literal change is in the air. “People think that the prevailing winds might even be changing, which is significant,” Chaim says. A month earlier, in June, unstable ice remained in the Nain harbour, landlocking the town. She had a conversation with her daughter’s grandfather about it. “He was talking about how we’re getting a lot of southwest winds, which is strange because it’s usually easterly winds,” she says. “It made for the ice to just stay there for a long time as opposed to getting blown out, which is what normally happens in that time of year, which then opens the harbour again.”

Maps of the Torngats, paintings, sketches and cards from previous visitors line the walls of the dining room at base camp. There’s a telescope perched at one of the windows to help sight far-off wildlife or icebergs that tuck into the bay. Sometimes you don’t need it: a minke whale spent an hour one day diving in and out of the waters at the end of the dock, in plain view of anyone here.

One morning after breakfast, Eli Merkuratsuk asks if I’m afraid of polar bears. I’m not, I tell him, as much as I thought I’d be. That’s because he’s a bear guard here, along with a handful of others, who keep their eyes on the margins of base camp. Margins also delineated by a 15,000-watt bear fence. Outside the safety of that electrified fence, the armed bear guards travel everywhere with us. On a short hike from camp, they’re perched at the highest vantage points. On boat and helicopter rides, they’re the first to any site and the last to leave.

Later that day, bear guards triangulate around a group of us who have travelled by helicopter and boat to Sallikuluk, or Rose Island. We’re an eclectic bunch, including tourists, Inuit drummers flown up from Goose Bay and the youth group.

A mother polar bear and her two cubs swim off the island and mount the shore across from it as we arrive. Soon, one of the drummers points to the ground where a fleck of Ramah chert glints in the sun. The foggy grey stone is found only in Ramah Bay, halfway between Saglek and Nachvak. But tools Inuit carvers made from it, and the flecks they left behind, can be found up and down the Labrador coast and as far south as New England.

We walk around the island, stopping at a row of sod houses and a massive whale bone beside them, and at a mass grave that was built after a palaeontologist in the 1970s stole the remains of 113 Inuit from the island. They were repatriated in 2005 and reburied with their possessions. Standing at the site, a Parks Canada guide tells us through tears that she pictures children playing by the shore here and women sewing. After a moment of silence, the drummers perform a song and people quietly place rocks at the cairn. All the while, the bear guards watch the landscape around us.

We return to base camp by way of a meandering boat ride. Zipping through the arms of Saglek Fiord, between sightings of polar bears and tundra black bears — in one case, within 20 metres of each other — bear guard Joe Atsatata tells me he was up here in March with Merkuratsuk getting caribou. (The park is the only area in Nunatsiavut where caribou hunting is allowed, as the Torngat Mountains herd is in a healthier state than those farther south.) They both have cabins in the area and that’s the best time to come for ice stability. With the ice so hard to predict, they’ll often travel on land instead.

Throughout the Torngat Mountains are hundreds of sites that show where Inuit once lived, harvested and fished, some dating back thousands of years.

It’s something Lena Onalik, an archaeologist with the Nunatsiavut Government had made clear to me back in Nain, before I arrived in the Torngats. “ What I always like to say is that, anywhere that looks like a nice place to go ashore, somebody already had that thought and there’s probably evidence of their visit,” she says, sitting in her office with heritage program co-ordinator Deirdre Elliott.

Onalik and Elliott visited an island just south of the Torngats border with a woman who spent her summers there growing up. Sophie Keelan remembered her father catching a beluga whale there, and where its bones lay next to their tent. She set foot on the island for the first time in 60 years and knew exactly where to go: they found a tent ring and beluga skull next to it.

Giving directions like you would to a tourist on a street corner, Keelan tells me over the phone where they harvested mussels and char, and where a shaman’s skull sits near the shore of Nachvak Brook — if it faces the water it will be a good year for fishing; if it faces land, not so much. These places and their importance are still clear in her mind.

“Mammals from the sea, we hunted them for survival and food,” Keelan, who lives in the Nunavik community of Kangiqsualujjuaq, or George River, says. “Even mussels, seaweed and urchins. And ugly fish — you know, you’ve seen ugly fish — the other kind with lots of spikes on the head?” She asks it with a laugh and, in fact, I do know what she means. Sculpin trawl the seafloor. When I first cast off the dock at base camp, Destiny Solomon, the drummer who found Ramah chert on Sallikuluk, sarcastically warned me to reel in quick and not let the hook hit bottom, because she wouldn’t be helping me take sculpin off.

Archaeology is helping to understand the shift in animal populations that use Torngats waters, Elliott explains. It’s a record of both the people and the environment. Take the bowhead whale bones that have been found on Sallikuluk, in Nachvak Fiord and elsewhere, she says. “When was the last time anyone saw a bowhead whale in the Torngats?”

Up until the 1700s, the Arctic and subarctic species was hunted along the Nunatsiavut coast, both by Inuit and Basque whalers, but haven’t been spotted in these waters in a century.

Data from pollen studies, ice cores and other sources can show how over extended periods of cooling or warming, people adapted and changed their way of life, Elliott says. “There is one big [period of warming] that happened 800 years ago that essentially resulted in the loss of a culture,” she says. “That’s when the Dorset Paleo-Eskimo just disappeared. The climate warmed and it seemed like they didn’t know how to cope.”

It’s a reminder that creating a conservation area does not freeze a place in time. The effects of climate change, of disasters in far-off but still-connected places will not spare this place because it’s been granted a new title. Forest fires don’t stop at the borders of parks. But that title does grant immunity from some threats: offshore oil and gas and mineral development are not permitted within a national marine conservation area, though there does not appear to be any immediate interest in mining the seafloor here. Perhaps more importantly, the designation represents an intention to focus resources on this place, to learn more about it, what’s here and how it’s changing.

And to bring more attention to a place that was visited by less than 500 people this year.

“You see where I grew up?” bear guard Merkuratsuk asks me when I return from Nachvak Fiord. “That’s good.” More people visiting the area is a good thing, he says, it’s more people appreciating what it is: arguably, the most beautiful place in the world.

On our first of three last nights at base camp — as the fog creates a ceiling no helicopter, let alone plane, can pass through, delaying our departure — Saunders hooks her laptop up to a screen. She shares her own story of navigating the bumps of academia to take on her current role, and what some of her research projects entail. A crowd of base camp staff and visitors huddle under knit blankets to listen, the mid-20-temperatures of Nain long behind us.

“We’re always changing and adapting to what people want,” Saunders says of her research priorities. Double-crested cormorants are moving into Nunatsiavut, and that’s happening fast, she says. Another bird they call “lesser geese” started showing up eight or nine years ago, and the research team of the Nunatsiavut Government still isn’t sure what they are. “So far, they’re not cackling geese, and that’s all we know,” she says.

And people are always interested in char, she says, so they want to know what goes on with their habitat. “For Inuit, it’s a holistic picture of everything,” Saunders says.

Back in the dining room at base camp, chef Trudy Metcalfe-Coe steps out of the kitchen to chat with me about her connection to this place.

Her father relocated from Hebron when he was 11 years old. He was the first mayor of Nain, a linguist, interpreter and writer. He had his struggles, Metcalfe-Coe says, as did so many people who were forced to leave their home. “But he was always somebody who everybody loved.” In 1988, when she was 22 years old, she moved to Ottawa. She came up to base camp last summer for one week, largely motivated by the chance to stop in Nain on her way up, since she hadn’t visited in more than 25 years. And she wanted to see Hebron, her father’s hometown, now a national historic site, where the Nunatsiavut Government is restoring the old mission buildings.

Metcalfe-Coe knew she had some family in Nain, but she was floored by how many relatives she found. “It was just crazy. Like I had no idea, there’s so much family up here that I didn’t even know existed,” she says. But they knew about her. Person after person came up to her when she first arrived at base camp, introducing themselves as her relatives — including Merkuratsuk and Atsatata, her cousins. In total, she met 23 relatives that week.

Family ties are also part of what brings the youth group here. “This is an opportunity for youth to come to where their parents or grandparents or great-great-grandparents used to live. So it’s like a return to the homelands, even though we aren’t the ones who grew up here,” youth leader Dicker says. “I think it’s important for people to be reminded or remember who they are and where they come from.”

On our final morning at base camp, the ceiling of fog finally starts to lift. The gossip around camp is that there’s a polar bear on the backside of an iceberg that drifted into the bay overnight. A few people say they’ve seen it through the telescope, poking its head up occasionally. Others say the bear is just waves crashing up over the smooth curves of the iceberg. As we make our way down to the boat to investigate, a few women from the kitchen, sitting outside for a smoke, warn us it’s out there. We zip across the bay in ten minutes to reach the iceberg — an electric blue and white piece of modern art. But the polar bear, if there ever was one, is gone.

This story is part of Spirits of Place, exploring the many ways Indigenous communities and nations are enacting their responsibilities to their lands, waters and future generations. It was made possible by funding from the Institute for Journalism & Natural Resources, as well as the Metcalf Foundation and MakeWay Foundation. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, the foundations have no editorial input.

Content for Apple News or Article only Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. This...

Continue reading

At a crucial point in their research, biologists are scrambling to find new support for...

From True Detective to The Grizzlies, the Inuk actor is known for badass roles. She's...

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...