Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

This story is part of Toronto’s Climate Right Now, a collaboration with The Local about vulnerability and adaptation in Canada’s largest city.

Hundreds of years ago the northern shores of Lake Ontario, not far from the mouth of the Don River in Toronto, were home to a vast marshland. If you stood at what is today Cherry Street and Villiers Street and looked to the north, you’d see a great forest. To the south, a beach that stretched for miles in both directions, finally meeting white bluffs in the east. And all around you, swaying bulrushes and other wetland plants.

And then, English colonists established a naval base called Fort York. A town grew around it, year by year, displacing Indigenous communities and wildlife. Beaches and wetlands became shipyards, warehouses and eventually oil refineries and manufacturing plants. The harbour was filled in so people could build even more. Toronto stretched and heaved past the original boundaries of York, the population rapidly increasing as the 21st century dawned.

Standing today at the intersection of Cherry and Villiers, the view in the distance is a forest of condos and skyscrapers. The air smells of metal and earth — the byproduct of thousands of kilos of dirt being moved into piles several stories high every day.

This neighbourhood is now undergoing another transformation. An unprecedented public works project is forging a river valley, raising the land height, and carving out an entirely new island on Toronto’s waterfront. When Villiers Island is complete, it will be a neighbourhood built from scratch, with almost 5,000 new homes for about 10,000 people. It will not only be one of the first “climate positive” communities in the city, but a community built to withstand the climate emergencies to come. It is a dream of a (mostly) car-free neighbourhood, where apartments are heated by geothermal energy and residents are only steps from boat launches and bike paths, surrounded by reinvigorated wetlands and greenery.

It’s the next evolution for this neighbourhood, and perhaps a model for neighbourhood building worldwide — though what the end product will look like still remains to be seen.

Toronto has flooded before and it will flood again — more often and more dangerously. According to the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority, climate change will bring more severe storms to the city, along with about 10 per cent higher average precipitation by 2040. This will cause property damage as well as contaminated runoff that can affect the quality of our drinking water and aquatic ecosystems. In 2013, the city got a preview of how bad it could get; a torrential storm dumped 126 millimetres of rain on Toronto, stranding a GO Train in the Don Valley where passengers reported seeing a snake slithering through the cars.

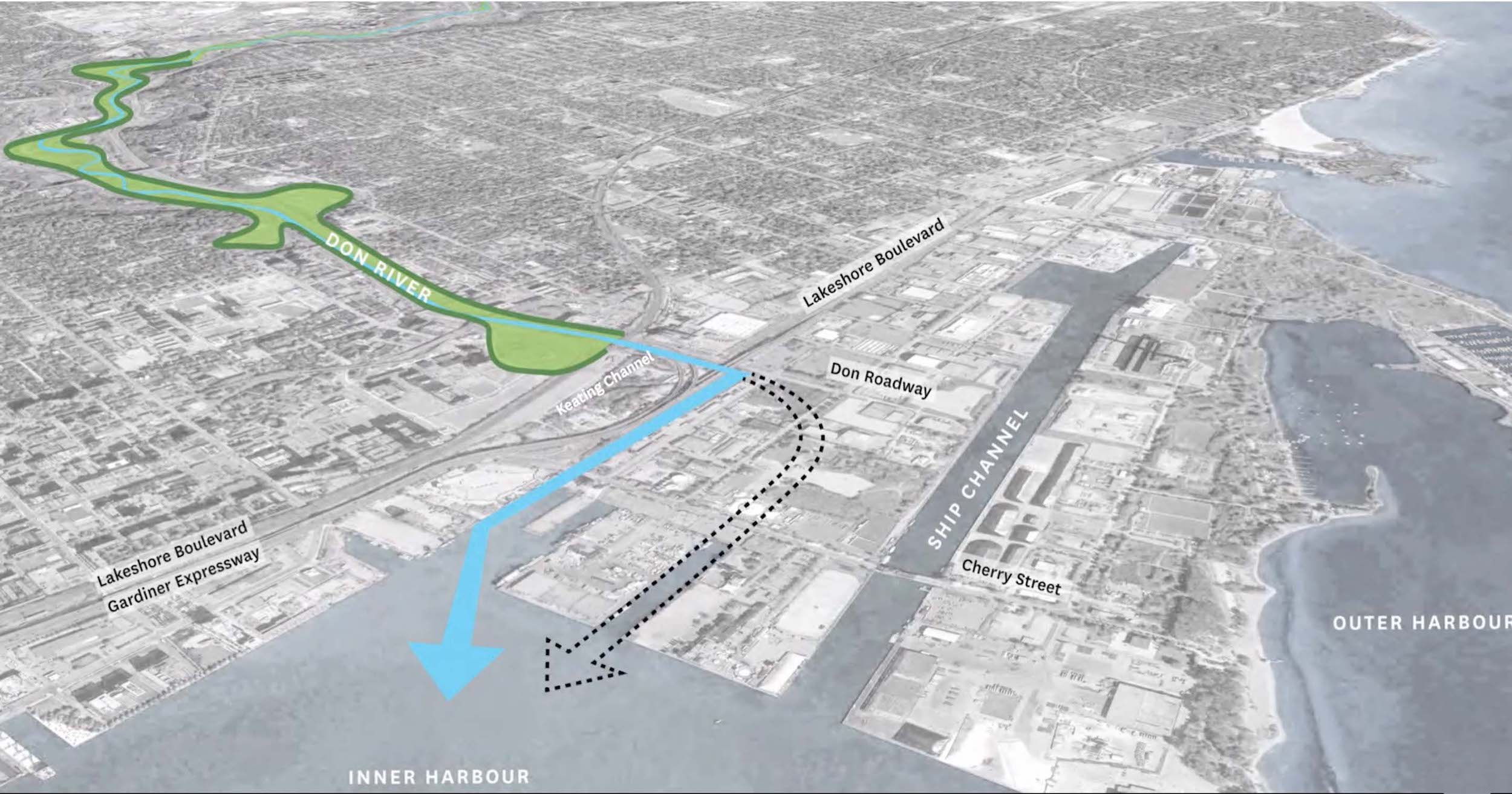

That water needs to go somewhere. Villiers Island is part of a larger plan to ease flooding, and send that water into floodplains and, eventually, back to Lake Ontario. The new mouth of the Don River will extend south of Commissioners Street, emptying into the harbour. The Keating Channel, just north, will remain, effectively providing two release valves for stormwater rushing down the Don River. The new valley system around it will act as a floodplain, able to absorb more water in the event of heavy rain. In the process, it will renaturalize what was once a heavily industrialized neighbourhood. New wetlands will provide support for aquatic ecosystems. Large debris from storms will drop out at the widened river upstream, and be filtered through the soil as it makes its way through the river valley, cleaning the water.

This plan also presented a new opportunity. Toronto is in desperate need of housing stock. Greater Toronto’s population will likely increase from 6.2 million people to eight million people by 2030, and to 10 million by 2045. Within the core, there is limited space where new buildings can go up, and exclusionary zoning regulations prohibit building anything but single family homes in many neighbourhoods.

Villiers Island provided an opportunity to design a neighbourhood not quite from scratch, but close. “I would say this was both a blank canvas and at the same time a very, very richly populated canvas,” says Michel Trocmé, a partner at Urban Strategies, the firm that created the Villiers Island precinct plan.

If completed as currently planned, Villiers Island will have a mix of medium and tall buildings. A minimum of 20 per cent of units will be affordable housing. New Cherry and Commissioners streets will be modern thoroughfares, with room for pedestrians, bike lanes, light-rail transit and cars. Almost 3,000 people will also work on the island. Parking will be limited. “The plan is not about catering to the car,” Trocmé says.

That’s one way the project is trying to reach its goal of being a climate positive community: a place that has net-negative greenhouse gas emissions. “Ensuring that there are active public and low-carbon opportunities for transportation is vital to achieving the climate positive goal,” says Aaron Barter, the director of innovation and sustainability at Waterfront Toronto. Among the design recommendations being implemented on the island are building to Passive House standards, which require tight insulation and great ventilation so minimal heating or cooling is needed, and organizing buildings on the island so that they can harvest solar energy. Since the precinct plan was released in 2017, the planners have favoured a plan that would use geothermal exchange to heat buildings. This would likely produce an excess of energy than is actually needed for the neighbourhood. The extra energy could then be rerouted to other places, helping Villiers meet its climate positive goal.

The construction itself aims to reuse materials. David Kusturin, the chief project officer at Waterfront Toronto, navigates the mounds of dirt at Villiers Island like he can already see the neighbourhood that will one day be there. His role is strategic leadership of the project, which on a typical day means overseeing excavation, where huge machines are digging out the river valley.

But, last year, Kusturin got involved with show business. The television show The Expanse was filming its final season and the crew had built a forest inside one of the warehouses on Cherry Street, within the construction zone of Villiers Island, complete with actual trees. After filming was done, they had to get rid of them. “Why don’t we just take them from you?” Kusturin asked the producers. Waterfront Toronto bought them, and now these trees will become part of the wetlands and river valley.

While buying trees from a movie set was an unusual example, Kusturin says that as they uncover old concrete blocks and peat, it has been reintegrated into the site.

“It’s amongst the largest projects of its size in the world,” Barter says. “And across Canada, it really stands alone as a master-planned precinct that has this ambitious goal of being climate positive.” While the team has looked at some precedents to inform its planning decisions, much has been custom developed for the site, with experts in urban planning, construction, landscape architecture and more pitching in. Some of this knowledge in planning will, inevitably, filter into other city projects over the years.

Pitmaster Lawrence La Pianta opened his restaurant, Cherry Street Bar-B-Que, in 2016. He chose an industrial area because it gave him freedom to pursue his craft exactly as he wanted. La Pianta’s cooking style requires barbecuing meat all night over a wood fire — he and his staff chop the wood on site. “I needed to be in an area where I’m not going to get my neighbours saying, ‘Oh, all I smell is wood burning all the time,” he says.

The Villiers Island site may not have been residential but it is still a neighbourhood. Just around the corner from La Pianta’s restaurant is Cherry Beach Sound, a recording studio in an old munitions factory. There were once functional storage facilities and metal recycling — one of the last true industrial areas in Toronto, where lots of people worked.

While a few heritage buildings have been retained, including the former bank that houses Cherry Street Bar-B-Que, most of the buildings that these businesses called home are gone. Villiers’ planners hope that some of those businesses will come back or, like Cherry Street Bar-B-Que, stick around. But creating a community is a tricky business.

Alex Bozikovic, The Globe and Mail’s architecture critic, believes the current design for the precinct endangers attempts at building community ties on Villiers Island. “This is going to be 10,000 people, slightly isolated,” he says. “It doesn’t have offices, retail and cultural facilities right on the doorstep. It’s got this chunk of stuff surrounded by … empty space.”

He believes this could be combatted by increasing the density of the area, which would not only house more people, but likely take more cars off the road if they are given viable alternate transportation options. Instead of driving in from the suburbs, they could bike or take the light-rail transit to jobs in the downtown core. It would also create a sense of enclosure that makes people want to stay in a neighbourhood.

Some of the medium density in Villiers can be attributed to the climate positive goal for the area. In Canada, buildings up to 12 stories tall can be constructed using mass timber, which is more environmentally friendly than building with concrete and steel. Letting buildings get more sun exposure also means they are less expensive to heat in the winter, and tall buildings cast shadows that make this more challenging. Passive housing standards, such as overhangs and exterior sunshades, will minimize the need for air-conditioning in the summer. However, housing more people where they don’t need cars may offset some of these losses. Bozikovic notes it’s challenging to figure out which is most sustainable in the long term.

Waterfront Toronto is also building Villiers to be climate resilient. The weather is only going to get worse. “So what we ask [in development agreements] is the design teams take into account a post-2050 climate and incorporate that as part of their energy modelling, to make sure that as we have more extreme weather or heat days during the summer, that these buildings will be resilient in the face of those changes,” Barter says. Plans also have to include backup power and refuge sites in the case of emergencies.

“The thing about cities is they take time and patience, and they take the dedication of a lot of different people,” Trocmé says. To make Villiers a place people want to live and visit, you need interesting businesses and community organizations who will bring the area to life.

Villiers Island is happening, no matter what. But exactly what that neighbourhood will look like in the end is still an open question. The procurement process for developers hasn’t even started yet. The earliest shovels will be in the ground for buildings is 2025, and Kusturin says that is an ambitious goal because there is still much excavation that has to be done.

But it leaves a few years for Torontonians and planners to figure out what kind of neighbourhood this will be. And La Pianta is staying as long as he can make a go of it while surrounded by excavations for a whole new community. “I think it’s gonna be a beautiful, amazing neighbourhood when it’s finally finished,” he says. “I hope that people make room for Cherry Street Bar-B-Que to remain here and be a part of the neighbourhood in the future.”

Until now, most of the work on Villiers Island has been hidden behind fences. But later this summer, Torontonians will finally get a glimpse of the vastness of this undertaking. The original Cherry Street bridge will be closed so that construction crews can finish excavation of the river mouth, and cars will be rerouted to the new bridge. It’s a modern white and yellow piece of infrastructure that wouldn’t look out of place in a sci-fi film. From there, people will be able to clearly see the length and breadth of the work that has been done. “I think they are going to be gobsmacked when it opens,” Kusturin says.

While the mounds of dirt will still be there, more plantings will be in the ground. Already, wildlife is finding its way to the site — some excavation had to be halted after bank swallows, a threatened bird species, built nests on the site. Kusturin expects it won’t be long before more animals follow. Planting has slowly begun, starting the process of renaturalization. Felled tree stumps, shipped from northern Ontario, line the river banks where, one day, they’ll become habitats for fish.

There was also a most unexpected discovery. A peat layer, exposed to the elements for a month or two, suddenly sprouted. “It wasn’t the usual weeds we see, it was bulrushes,” Kusturin says. A group from the Toronto and Region Conservation Authority determined that when the peat was exposed, 100-year-old seeds from the Ashbridge’s Bay Marsh germinated.

Some of the soil is now being studied at University of Toronto, to see if more native plant seeds can be found. But the bulrushes are going to be planted in the river valley, where they’ll grow anew.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion