Celebrating 7 years of The Narwhal — and gearing up for the next 7

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The Trans Mountain pipeline, owned by the federal government, is a culprit in the destruction of endangered spotted owl habitat, The Narwhal has learned in a new twist to 11th-hour efforts to save the owl from extinction in Canada.

The B.C. NDP government, elected in 2017 on a platform that included using “every tool in [the] toolbox” to stop Trans Mountain from being built, quietly approved 24 new cutblocks for the pipeline in habitat federal scientists deemed necessary for the owl’s survival and recovery, including old-growth forests.

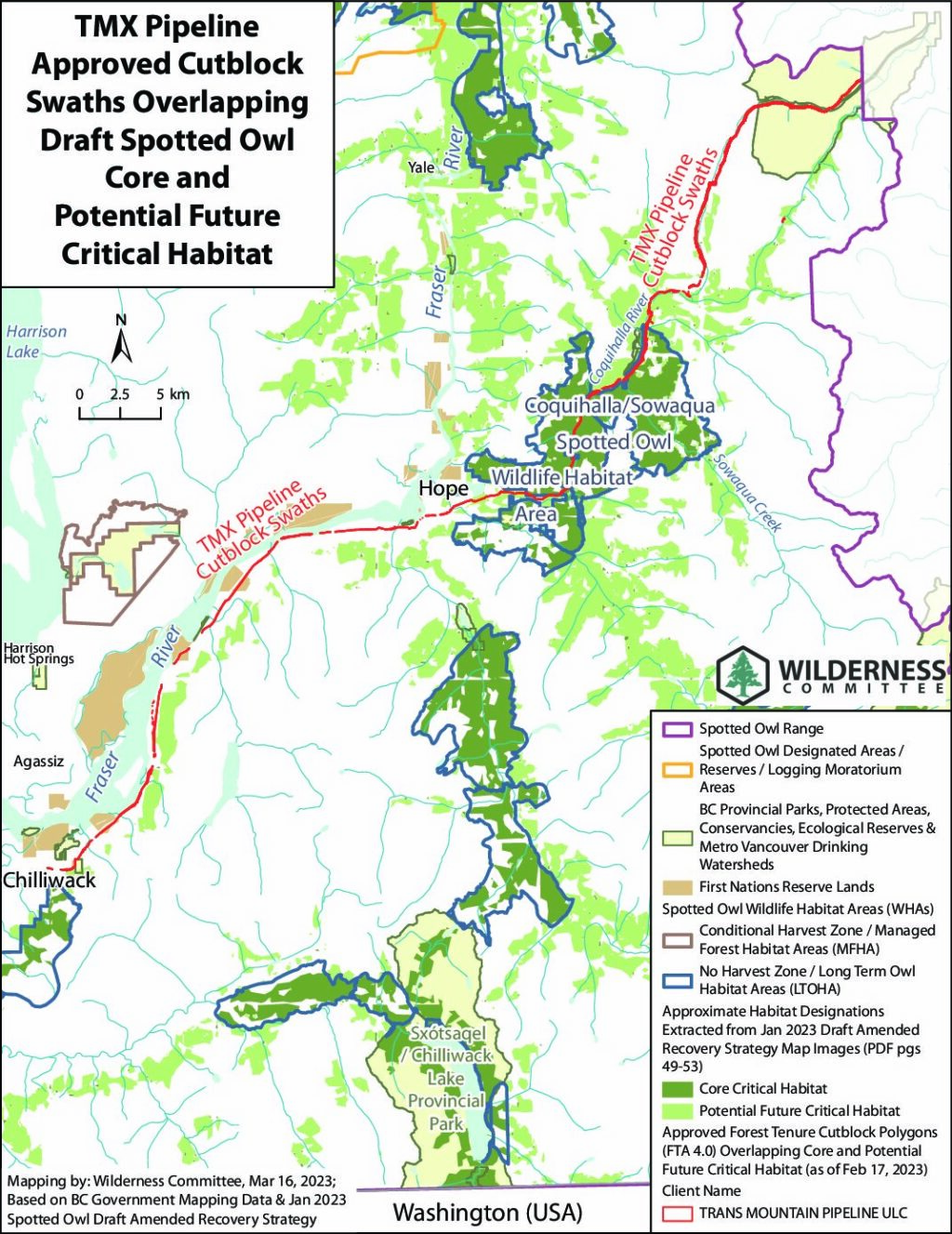

According to the non-profit group Wilderness Committee, the cutblocks fall in the Coquihalla River valley, east of Hope, and along the Fraser River between Chilliwack and Hope. A swath of cutblocks more than 10 kilometres long slices through the Coquihalla-Sowaqua wildlife habitat area near Hope, which the B.C. government protected for the spotted owl’s recovery. An additional cutblock awaits approval.

The pipeline’s destruction of spotted owl habitat puts the federal government, which owns Trans Mountain, in a very awkward situation. Under the Species at Risk Act, the government is responsible for identifying the owl’s critical habitat and taking action to prevent the species from dying out in Canada.

In February, federal environment minister Steven Guilbeault said he would recommend the federal cabinet issue a rare emergency order to protect the owl and its habitat in B.C., the only place in Canada where it’s ever been found. An emergency order — granted under the Species at Risk Act — would allow Ottawa jurisdiction over decisions that normally fall to B.C., such as whether or not to issue logging permits.

Andrea Olive, a University of Toronto professor whose research focuses on species-at-risk conservation, said clear-cutting spotted owl habitat for the Trans Mountain pipeline highlights a problem with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s message that Canada can both be a natural resource superpower and champion biodiversity and conservation.

“When push comes to shove, these are the decisions that we have to make,” Olive said in an interview. “We have a prime minister who keeps telling us again, and again, that sustainable development is possible. And that we essentially can have our cake and eat it too, or have our pipeline and the owl too.”

“This is messy,” Olive said. “This is really hard. And I don’t think we can, in this case, have forestry the way we’re having it and spotted owls, sadly.”

Only three spotted owls remain in the wild in Canada, following decades of industrial logging in the old-growth forests where the owl nests in cavities in large-diameter trees and preys mainly on flying squirrels and packrats. About 30 spotted owls live in aviaries at a multi-million dollar breeding centre in Langley funded by the B.C. government, where eggs are hatched in incubators in the hopes of releasing captive-bred owls into the wild. The first release took place last August, when three young owls born in the captive breeding program were set free near the Fraser Canyon (one later suffered an injury and was brought back into captivity).

Documents obtained by The Narwhal under freedom of information legislation show almost half of spotted owl core critical habitat — habitat that biologists, using the best available science, deemed necessary for the owl’s survival and recovery — was quietly removed from federal maps between 2021 and 2023, following negotiations with the B.C. government.

The removed area, which includes some Trans Mountain pipeline cutblocks, was renamed “potential future critical habitat” on maps published in January in a long-overdue proposed spotted owl recovery strategy. The designation is not a legal term and does not exist under Canada’s Species at Risk Act.

“Critical habitat” is a defined term under the Act, triggering certain obligations and requirements once identified.

According to the Wilderness Committee, the Trans Mountain pipeline cutblocks are among 200 the B.C. government approved that overlap with spotted owl “potential future” critical habitat. The proposed recovery strategy, open for public comment until March 27, gives the B.C. government up to 60 years to decide if “potential future” habitat merits designation as core “critical habitat,” triggering protections under the Species at Risk Act.

The cutblocks add up to almost 1,700 hectares, more than four times the size of Vancouver’s Stanley Park. An additional 43 cutblocks overlapping with “potential future critical habitat” await approval by the B.C. forests ministry.

Olive said the Species at Risk Act “means nothing” if it’s not enforced. “If we can just conveniently re-define critical habitat as industry needs us to, then what are we even doing?” she asked. “The whole thing is supposed to be science-led, science and Indigenous Knowledge. And we’re not listening to science, we’re listening to industry. When it’s inconvenient for industry, we’re going to redefine science. Is that really what we’re doing?”

The Trans Mountain cutblocks in spotted owl habitat are found in long swaths, some with overlapping persmits, as well as in three smaller sections, according to Geoff Senichenko, research and mapping coordinator for the Wilderness Committee.

A Sowaqua wildlife habitat area mitigation plan Trans Mountain submitted to the Canada Energy Regulator notes mature and old forests would be cleared for the pipeline. (The wildlife habitat area’s official name is Coquihalla-Sowaqua.) The plan says no spotted owls were detected during surveys. Appropriate measures will be applied to minimize the pipeline’s impacts to spotted owls, including retaining and “replacing” suitable nest trees and revegetation, the plan says. It does not explain how trees hundreds of years old will be replaced.

The plan also says Trans Mountain has evaluated potential offset measures. The company’s preferred offset approach is spotted owl “population management directed and implemented” by the province — achieved through financial contributions Trans Mountain would make to the breeding program. In October 2021, Trans Mountain announced it had donated $5,000 to the program to help feed the owls.

Guilbeault, in a February letter to B.C. Minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship Nathan Cullen, said a federal assessment had determined the spotted owl faces imminent threats to its survival and recovery. More than 2,500 hectares across spotted owl habitat had a high potential to be harvested over the next year, Guilbeault noted. “The complete or partial logging of these areas, distributed over a patchwork of spotted owl habitat, would alter the amount and configuration of their habitat, making the achievement of its recovery objectives highly unlikely,” he wrote.

Olive said her first thought, upon hearing of the emergency order recommendation, was “too little, too late.” We knew years ago that the spotted owl was in trouble and we also know habitat loss is the principal reason for its decline, she pointed out.

“This is ridiculous. This is way past the point of the precautionary principle.” The precautionary principle states that a lack of full scientific certainty shall not be used as a reason for postponing protection measures in the case of threats of serious or irreversible damage.

“We’re actually talking about a species that really is functionally extinct,” Olive said. “And that should be a huge deal, right? … It’s sort of already too late. If we had cared about that, then this [the emergency order] should have happened 10 years ago.”

She speculated the threat of an emergency order for the spotted owl might be a power play, possibly to convince the B.C. government to fulfill a commitment made in 1996 and enact a stand-alone law to protect the province’s 1,300 listed at-risk species. Only four species are protected under B.C.’s Wildlife Act, while the federal Species at Risk Act automatically protects species only on federal land — about one per cent of the province, including national parks and post offices.

The Act gives the federal government the power to step in if it believes a species faces imminent threats to its survival and recovery. Only twice in the Act’s 20-year history has federal cabinet issued an emergency order to protect an endangered species — once for the western chorus frog in Quebec and once for the greater sage grouse in Alberta.

Olive said it’s unusual for the federal government to threaten to override provincial jurisdiction. “That’s not generally how Canada operates. And so when you do it, you need to do it carefully. And you need to do it seriously,” she said. “I would hate to think that this is some sort of empty threat by the minister.”

In an emailed response to questions, Samantha Bayard, senior communications advisor for Guilbeault’s department, said the minister will make a recommendation to the federal cabinet in a timely way “for measures to protect [the] spotted owl from imminent threats.”

“The government of Canada is committed to acting on sound science and all available information when it makes decisions, and works in close consultation with affected parties,” Bayard wrote. In addition to the findings of the imminent threat assessment that informed Guilbeault’s opinion, she said a number of factors may be considered in a decision about the emergency order, including “views shared by Indigenous peoples, socio-economic and legal considerations, views shared by stakeholders, and efforts by the government of British Columbia to mitigate imminent threats.”

Guilbeault’s imminent threat assessment considered threats within proposed core critical habitat as well as additional areas of potential future critical habitat, Bayard noted.

“Environment Climate Change Canada (ECCC) is working with the government of British Columbia to identify additional measures to protect and recover this symbolic species and its old-growth forest habitat, and has initiated the process of consulting with Indigenous peoples.”

Bayard also said the amended spotted owl recovery strategy has not yet been finalized.

The department did not respond to a request for comment on the Trans Mountain pipeline cutblocks.

The B.C. government was not able to immediately respond to questions.

In an emailed response to previous questions about logging in spotted owl habitat, B.C.’s resource stewardship ministry said no cutting permits were approved in 280,000 hectares “already identified and protected by the province as spotted owl habitat,” including wildlife management areas.

The B.C. government also said it has protected enough habitat to support 125 spotted owl pairs, a claim disputed by independent biologists, who point to the owl’s demise as proof the habitat is not sufficient. “B.C. is committed to recovery, but this is going to take [time],” the email from the resource stewardship ministry stated. It also said recovery of the spotted owl population “depends on the successful reintroduction of captive-bred owls back into the wild.”

Last October, Guilbeault warned provinces and municipalities there will be no more tolerance for destruction of habitats containing endangered species, saying “the party is over.” Asked by The Narwhal to elaborate, Guilbeault said the federal government is looking “very closely” at wildlife listed under the Species at Risk Act.

Ottawa is currently negotiating with “many governments across Canada on a number of species,” the minister said in response to a question at a news conference in early March. Guilbeault cited caribou in Ontario and Quebec and the spotted owl as examples. “It’s a responsibility we have as a government to protect those species and obviously protect those species by protecting their habitats, there’s no two ways about it.”

If the spotted owl disappears from B.C., it will join 135 other species, including the black-footed ferret, on the list of wildlife extirpated from Canada. In December, the federal government signed a landmark global agreement committing to recover at-risk species and protect biodiversity.

Olive said all living things have intrinsic value and society should care about them simply because they exist. When species like the spotted owl disappear from Canada, “we are worse off, as a nation and as humanity,” she said. “Every time we lose a species, it’s losing part of us, it’s losing a piece of the global puzzle. And I think we should mourn the loss of all of those species who make up the larger whole. A piece of us is gone forever.”

— With files from Fatima Syed

Updated on March 17, 2023, at 3:01 p.m. PT: This story has been updated to include responses from Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits