Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

If all goes to plan, 30,000 Chinook salmon eggs will be fertilized upstream of Dawson City this summer as part of the Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation’s efforts to increase stocks of the vital fish.

For roughly two decades, fewer Chinook salmon have been swimming into Yukon, spurring the First Nation to develop a plan. Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in has been laying the groundwork to establish a full-fledged egg-rearing facility — featuring the first sonar system wholly owned by a Yukon First Nation — to bolster dwindling numbers of the species along the Klondike River, a tributary of the Yukon River.

“It’s one of our main traditional food staples,” Chief Roberta Joseph told The Narwhal, noting that citizens have been asked to voluntarily refrain from fishing Chinook salmon since 2013.

“Since time immemorial our ancestors have relied on salmon. Not only is it a food staple but fishing them is a time for families to bond and pass on traditional knowledge and stories. It’s a time of healing, of renewing spirituality and connection that our people have with the land.”

An egg incubation facility is a few years off, though. Gaps in research need to be filled. This is what the community has been trying to do for the last two years: study what works and what doesn’t via an in-stream incubation project. This will help them determine egg-to-fry survival rates, or how successful eggs are at growing into adolescence. They’re also measuring conditions such as water level, temperature and when the fish arrive. From this information they can replicate the ideal conditions for a high survival rate in the incubation facility.

But more time is needed after a poor run of Chinook in previous years has meant numbers for the project aren’t as high as hoped, said Ben Schonewille, a fish and wildlife biologist with Environmental Dynamics Inc., which was contracted by the community to help study the feasibility of the egg incubation program.

They’ve requested an extension to the in-stream incubation project for at least another year. The Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board is evaluating the proposal to extend right now and a public comment period will likely be launched soon, a spokesperson for the board said.

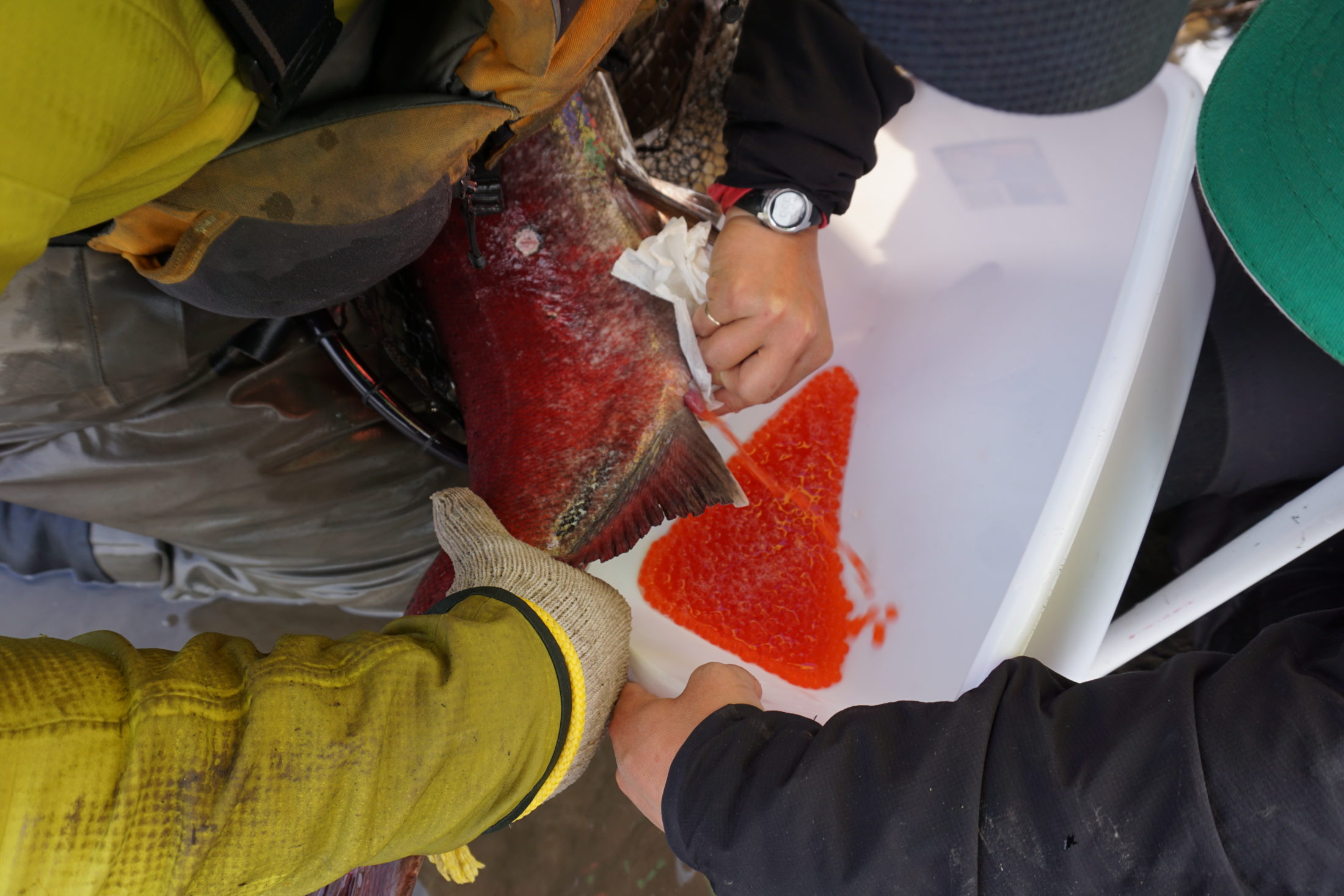

Since July 2018, egg-to-fry survival rates have been closely monitored through this project. Eggs are taken from females and are mixed with milt (semen) from males. The fertilized eggs are placed along with sediment into an incubation vector, such as a mesh bag, and then buried in the river. Researchers then dig up the bags and are able to gauge how many eggs inside have survived to the fry stage. This is called a “green egg” process.

Eggs are collected from a Chinook salmon to use as part of the in-stream incubator project aimed at increasing the dwindling population of Chinook in the Klondike River. Photo: Environmental Dynamics Inc.

Broodstock — the group of mature salmon that will be targeted by researchers for egg and milt collection — are located by helicopter at the peak of the salmon run.

But issues including water clarity and a lack of Chinook have slowed down tracking goals for the project, which follows a separate in-stream incubation effort in Yukon started by Teslin Tlingit Council in 2016.

The Tr’ondëk Hwëch’s project has a goal of planting a maximum of 30,000 eggs per year (to put this into perspective, one female contains roughly 5,500 eggs while spawning). Roughly a third of this goal was hit, or about 10,000 eggs planted, in both 2018 and 2019.

“We just could not catch sufficient broodstock, nor were we comfortable taking more eggs due to the poor returns to the Klondike in 2019,” Schonewille said, adding that while 30,000 eggs is the upper limit of the project, planting less than that hardly deems it unproductive.

According to Fisheries and Oceans Canada, the number of Chinook salmon that make it back over the Alaskan border into the Yukon to breed — known as treaty-obligated escapements — have been less than the number that left the territory for the past 11 years.

Last year, 42,052 Chinook salmon entered Yukon, said Elizabeth MacDonald, executive director of the Yukon Salmon Sub-Committee. This fell below the spawning escapement goal range of 42,500 to 55,000.

It’s difficult to pinpoint any one reason why fewer Chinook salmon are populating Yukon rivers, but low productivity and changes to ecosystems could be playing a role. MacDonald said salmon that come back from the ocean to spawn are yielding fewer offspring compared to a decade ago.

Impacts to marine or river habitats could also be affecting their productivity.

“Definitely climate change is having an effect, and there’s a lot more people, so anthropogenic effects, not so much in our neck of the woods, but along the B.C. coast with forestry and rural development — industry, let’s say,” MacDonald said. “No one knows for sure. But there’s always a cycle to salmon. Sometimes they do well, sometimes they do poorly.”

Critical to Tr’ondëk Hwëch’s salmon incubation facility is the introduction of a sonar system that tracks the number of Chinook salmon in the water. “The unit looks across the river channel and records sonar files which are then reviewed by a trained sonar technician to count the number of salmon that swim past the site,” Schonewille explained.

Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in plans to have the sonar up-and-running by July 1 in Dawson City. It will be the first system of its kind wholly owned by a First Nation in Yukon, said Schonewille, noting that citizens are to be trained in how to operate it.

The goal is to ensure there’s a baseline understanding of how many fish enter the Klondike, he said, adding that it will help to determine the capacity of the watershed in the future for hosting Chinook salmon — and that the aquatic ecosystem isn’t thrown out of balance.

“It’s really important because it provides a very accurate count of the number of fish that spawned in the Klondike in any given year,” he continued. “Once restoration work begins on a greater scale, we’ll be able to determine how successful it is.”

The lynchpin to all of this work is a Chinook salmon restoration plan that was first released in 2017. This living document is the basis for all future work regarding salmon restoration in the area. Underpinning it is Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in’s final agreement with the Yukon and federal governments, a section of which says that the community is responsible for preserving and enhancing the renewable resource economy within its traditional territory.

Final agreements signal that a First Nation has settled their land claims. Eleven of 14 Yukon First Nations (including Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in) have done so. They can create and enact laws, for example, and have far more jurisdiction than First Nations in southern Canada, most of which fall under the Indian Act.

The restoration plan’s message is clear: salmon are inseparable from Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in culture.

“Culture camps that bring Elders and youth together are a venue that allows traditional knowledge to be shared and passed on to the next generation,” the plan says. “These camps include activities that focus on all things salmon — harvesting techniques, preserving your catch, setting nets and special or traditionally used camping areas along the river, as well as spiritual practices, stories and songs that teach youth respect for the salmon.”

“Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in citizens are physically, culturally and spiritually connected to the Yukon River salmon fishery.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion