The Narwhal picks up four Canadian Association of Journalists award nominations

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Yukon government says there are more than enough Fortymile caribou to support opening the permit hunt, but its opening conflicts with a local First Nation’s request to hold off until a harvest management plan is completed in the coming weeks.

That plan will give Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation more say in managing the herd, which saw its numbers plummet in the 1970s and slowly increase during the intervening years to roughly 84,000 as of 2017.

Now is not the time to open the hunt, said acting Chief Simon Nagano, adding the First Nation’s citizens need the opportunity to give feedback on the plan first.

The First Nation is cautiously optimistic about the herd’s return to healthy numbers.

More than a century ago, there were so many Fortymile caribou crossing the Yukon River, near Dawson City, that someone could walk on their backs to get to the other side, Nagano said. This is what his great, great grandmother saw when the herd’s numbers were as high as 500,000 in Yukon.

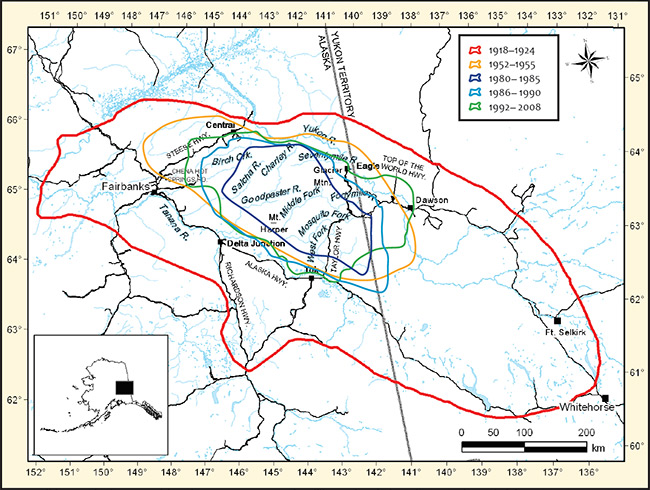

The Fortymile caribou herd’s historic range is shown in red. Over the past seven decades, that range has become smaller, and expanded again slightly in recent years to reach near Mayo, Yukon, in winter months. The herd’s summer grounds, though, have remained focused between Dawson City and Fairbanks, Alaska, causing congestion as the once sparse herd’s population grows. Map: Alaska Department of Fish and Game

The dwindling population of Fortymile caribou over the last few decades has prompted governments to restrict hunting the herd, including Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in First Nation, which asked its citizens to voluntarily refrain from killing any caribou (it recently organized its first community subsistence harvest in two decades). In 1995, the Yukon government put a ban on the permit hunt as the herd’s population dropped around 23,000.

After 25 years without a permit hunt, the Yukon government has opened two in the last year.

The first hunt started Jan. 1 with 220 permits available and only 14 caribou killed. The second opened Aug. 1, with 160 permits available.

This is also the second time this year Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, located in Dawson City, just east of the permit hunt zone, has asked the territorial government to call off the hunt.

“They could be holding off and listening to us until our harvest management plan is complete,” Nagano said.

Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in’s plan will lay out a joint approach to managing the herd with the territory, government to government. It will be presented to citizens at the end of August during the First Nation’s general assembly, and then finalized. But the Yukon government, Nagano said, acted too soon.

Yukon government regional biologist Mike Suitor told The Narwhal the herd’s health is top of mind and hunting is a necessary means of population control.

Nagano said he appreciates this rationale, to a degree, as hunting is a part of the forthcoming harvest management plan. But, he said, opening the hunt has cut First Nations citizens out of the decision-making process.

“Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in is the guardian of the land, the water, the wildlife and the air within our traditional territory and we take that very seriously,” Nagano said. “Without us doing [something] now, there’d be nothing left for the future generations.”

The First Nation’s citizens will decide whether the harvest management plan passes. That’s why it’s so important to give them a chance to weigh in on it, Nagano said.

“We want them to have confidence in hunting the Fortymile caribou again as a source of food,” he said, adding that this confidence comes from knowing the herd is being adequately managed. “The main reason is to reconnect our citizens.”

The plan outlines rules for harvesting from the herd and protecting its range, Nagano said. This could include ways to alert people to settlement lands within the range, protecting berry patches for harvesting, limiting off-road vehicles in certain areas — particularly where there’s lichen, a staple food for the caribou — and measures to safeguard the Fortymile herd itself.

These rules were contributed both by the Yukon government and the First Nation. Right now, Nagano said, the approach to the herd’s management is siloed, with much of the oversight defaulting to the territory.

Having the management plan in place will bring the two governments in line.

“We could share information such as studies on movements, habitat, diseases,” Nagano said. “With a harvest management plan, we will know (the Yukon government’s) studies, and we don’t have to go out there and put any pressure on the Fortymile caribou by doing everything twice.”

Nagano said opening the hunt without that plan contravenes the First Nation’s final agreement, which lays out its land claims and responsibilities for co-management of wildlife, among other things. The agreement stipulates that the Yukon government and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in establish a working group to protect and promote the growth of the Fortymile caribou herd.

“It’s not very hard for them to look at it and read it,” he said. “They always seem to bypass it and, more or less, carry on to their decision … At the end of the day, what you’re doing is confusing the public and you’re not making friends with Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in.”

Suitor said the First Nation’s final agreement has been followed, adding the two governments have worked on the management plan since 2013 and the territory is fully committed to seeing it finalized.

“At the end of the day, we feel that a licenced hunt is not contingent on having a finalized harvest management plan,” Suitor said. “We’ve gone even more conservative than what was in that draft plan to try to ensure we’re not impacting citizens and rights.”

The fact is, according to Suitor, 84,000 caribou is a problem because the herd’s range has shrunk over the years and can only sustain so many animals.

“This is a lot of caribou. If you look at any herd in the world right now, that’s starting to get up there now, in terms of the size of the herd,” Suitor said. “There’s more than enough caribou to have a sustainable harvest on a herd that big.”

The Fortymile caribou herd, pictured here in northwestern Yukon, relies on sustenance from willow, grasses and other foliage in its summer grounds for the cows to gain enough weight to give birth the following spring. Photo: Selkinshome / Flickr

If the herd gets too big it will be faced with a steep decline, he said. A major factor in this is the herd’s summer habitat, where the availability of willow, grasses and other foliage for cows to eat ensures they gain enough weight to give birth the following spring.

When the summering grounds are crowded, food is scarce.

“That metric, in particular, we’ve seen decline very quickly,” Suitor said. “That’s been a caution flag for us all along.”

The problem is the caribou herd hasn’t expanded its summer range. Instead, it returns to the same one, year after year, stretching from north of Fairbanks, Alaska to southwest of Dawson City.

This is where hunting comes in, he said, as an interim measure to control the population.

“Slowing down herd growth is something that is considered to be very important,” Suitor said. “We’ve got more caribou than can be used.”

Another factor in the Yukon government’s decision to open the hunt, Suitor said, was that had it not, Alaska would have taken Yukon’s share of the caribou. An Alaskan harvest management plan, completed last year, clarified that if the Yukon government neglected to open a hunt, Alaska has rights to its allotment, he said.

The herd’s annual range slants southeastward from around Fairbanks toward Mayo, Yukon. There’s no managing the herd without input from the state, Suitor said. Caribou can’t be hemmed in — they go where they want, making their management a transboundary issue. As such, hunting allotments are set between the state and territorial governments.

While Yukon’s ban was in place over the past two decades, hunting of the herd never stopped in Alaska. Last year, Alaskan hunters harvested 2,900 caribou, more than its quota of 2,200, Suitor said, noting there’s no penalty for going over this allotment.

“Although Alaska did harvest over its quota last year, the overall sustainable harvest identified for 2019-2020 was not exceeded,” he said. That allocation has never been exceeded since Yukon and Alaska implemented restrictions on the harvest in 1995, Suitor said.

During discussions around Alaska’s new management plan, which included the Yukon government and Tr’ondëk Hwëch’in, Suitor said state officials also voiced concern over the potential for a major population decline as the large herd was over-grazing and trampling its summering grounds.

“Alaska is pressing us very hard to ensure that the herd health is maintained, because the herd is very important to them, just like it’s very important to us.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...

Locals in the small community of Arborg worry a new Indigenous-led protected area plan would...