Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

When Tsleil-Waututh families sat down for dinner 500 years ago, what was on the menu? Thanks to new research, the First Nation has detailed data on what their ancestors were eating before colonization — and what their lands and waters might provide again in the future.

səlilwətaɬ (Tsleil-Waututh Nation) worked with researchers from the University of British Columbia to estimate how Tsleil-Waututh people got their calories pre-contact, combining archeological evidence and ancestral knowledge to reconstruct the average diet.

In the hən̓q̓əmin̓əm̓ language, səlilwətaɬ means People of the Inlet. The inlet falls within the traditional and unceded territories of Tsleil-Waututh (səlilwətaɬ), Squamish (Sḵwx̱wú7mesh Úxwumixw) and Musqueam (xʷməθkʷəy̓əm) Nations.

Today, səl̓ilw̓ət (pronounced suh-ley-l-wut, also called the Burrard Inlet) is home to Vancouver and surrounding cities and it has been heavily industrialized and polluted. The shallow waters and beaches that once lined səl̓ilwət have been dredged, flooded and built upon. Traditional foods are found at a fraction of their former abundance, and many are no longer considered safe to eat due to contamination. Tsleil-Waututh is fighting to restore the inlet in the face of habitat destruction and a biodiversity crisis. Rebuilding the nation’s ancestral diet is one piece of the puzzle, measuring what has been lost and can be revitalized to support local food security.

“We should be able to eat from the water. We should be able to use it,” Michelle George, Tsleil-Waututh member and cultural technical specialist with the nation’s Treaty, Lands and Resources Department, said.

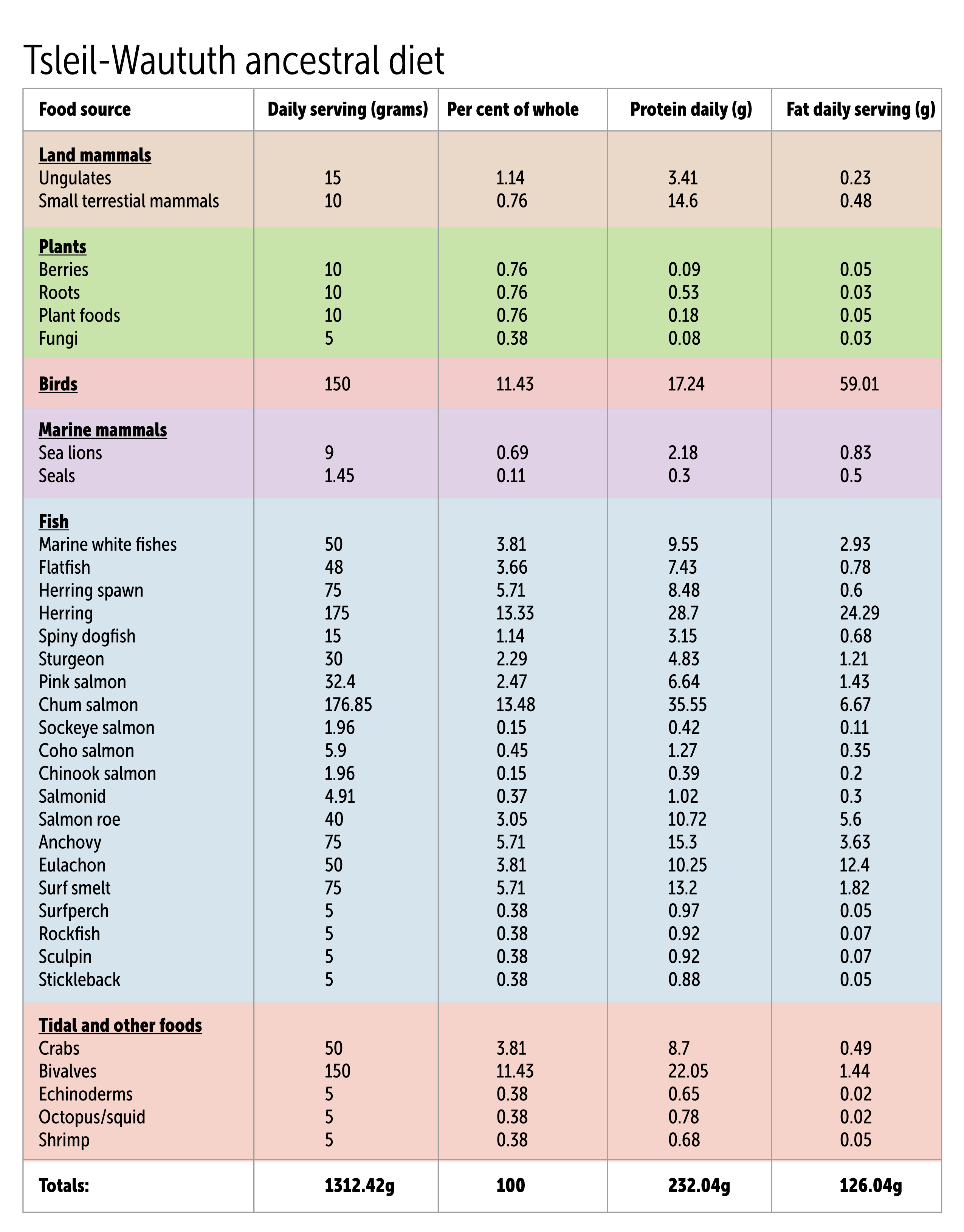

According to the new study, presented in April at the annual meeting of the Society for American Archaeology, the historic Tsleil-Waututh diet was very high in fat and protein. Before colonization, citizens ate 126 grams of fat and a whopping 232 grams of protein per day — two to four times as much protein as a 150-pound person would typically eat today. Salmonidae (a family of fish that includes salmon, trout and char), forage fish (like herring, smelt, anchovy and eulachon), shellfish and marine birds were the top foods eaten day-to-day.

The research is modelled on the years between 1000 and 1792, the approximate date of European contact, and based on a population of 10,000 people.

The high-fat diet “would have been incredibly heart healthy and high-energy providing,” Meaghan Efford, a PhD candidate at the University of British Columbia and lead author of the study, said.

Efford said she hopes people look at this study and think of what could be possible again, rather than as something stuck in the past.

“By looking at what was possible pre-contact … we know what to improve and what direction to go in in order to heal the inlet.”

“My family always knew that this is what we did, but being able to prove it scientifically was the next big step,” George said. “We are able to hold that up to other governments and be able to show this is true baseline.”

Efford was a professional ballet dancer before getting into science. She loved the storytelling of dance, and fell in love with archeology when she realized it allowed people to “tell stories about the past.”

During early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, when Efford was unable to do research in the community, she spent hours alone going through archeological material at Simon Fraser University. She was struck by the “staggering” abundance of salmon bones. She wondered just how much she could learn about what people were eating, a question that aligned with the nation’s research goals.

“We unearthed — no pun intended — this really robust data set,” she said.

Efford built a computer simulation of how human and animal populations would have looked in Burrard Inlet during the study period, based on historic population data, and considered how much would have been harvested according to this reconstructed diet. George was struck by how the simulation showed a harmonious relationship between humans and all the animals of the land and sea; Tsleil-Waututh could meet their dietary needs through harvesting without depleting the animal populations. When Efford experimented with removing a species from the model, the balance in the simulated ecosystem was thrown off. To George, it demonstrated how “everything is connected.”

“[Efford] would take an animal out of the simulation, and once she took something out of that ecosystem, the system started to collapse,” she said.

The simulation suggested the diet “could sustainably be harvested over generations with no problem,” Efford said.

Tsleil-Waututh harvested crabs, clams and other bivalves. The study estimates a Tsleil-Waututh person ate about 150 grams of bivalve mollusks per day — more than 11 per cent of their daily diet. Millions of clamshells have been found at the təmtəmíxʷtən village site, and archeological evidence shows butter clams, littleneck clams and cockles have been part of səl̓ilwətaɬ diets for at least 3,000 years. Tsleil-Waututh also harvested crabs and other bivalves from səl̓ilw̓ət.

They hunted seals at sea, and mammals like deer, elk and rabbits on land, but these were much less significant food sources. The study estimates land mammals made up just under two per cent of daily food, while just under one per cent came from marine mammals. Ocean foods are the heart of their ancestral diet.

Efford was surprised that research suggests the caloric needs of hunter-gatherer societies are not that different from moderately active adults today. She looked to the Hadza of northern Tanzania, who still live as a hunter-gatherer society. Adult Hazda women consume an average of 1900 calories per day and adult men consume 2,600 calories per day. Hunter-gatherers are active, but they are “not over-extending their body’s ability,” she explained.

The reconstructed diet is an average — it doesn’t consider seasonality, ecological shifts or social factors like class or profession. The researchers also didn’t consider food imported from outside the inlet. Incorporating all of these variables would have taken several more years, Efford said.

Through urban and industrial development, Burrard Inlet has lost 55 per cent of its tidal zone, a total of 945 hectares — an area more than twice the size of Stanley Park.

For George, the ancestral diet revealed how profoundly her ancestors’ diets were disrupted by colonization. Herring were all but eradicated from the inlet between about 1880 and 1930. Settlers tossed dynamite into the inlet to kill as many as they could as quickly as possible so they could use herring oil to grease logging roads. As a result, the fish has become scarce in modern Tsleil-Waututh diets, but the study shows herring was a historically important mainstay.

Some herring have returned, so the nation has hosted herring barbecues in recent years. Many people had never tasted herring or their roe before. “Getting it back in people’s palates was very cool,” George said.

The inlet has lost its “nutritional value,” George explained. With colonization came the whaling industry, which drove down whale populations. Shellfish, salmon, forage fish and marine birds depend on tidal zones, but shallow banks were dredged to make way for industry. Pollution from sewage, household refuse and industrial waste has made shellfish largely unsafe to eat for decades.

Despite the well-established impacts on the marine ecosystem, the B.C. government still allows corporations to dump contaminants like oil, lead and copper into the inlet. A recent video of coal spilling into Burrard Inlet raised questions of how often spills and leaks go unreported.

Industrial contamination means Tsleil-Waututh must undertake extensive testing for even a small clam harvest. In February 2023, the nation collected about 15 kilograms of clams that came back clean from the lab — a success, but still not enough for every member to have a single meal of clams.

“Even in my time, our families used to gather and go down to the beach and it would be like a seafood bake,” Micheal George, Michelle’s father and a cultural advisor with the nation, previously told The Narwhal. “We just called it lunch.”

Tsleil-Waututh Nation and its research team produced a series of reports analyzing cumulative effects of industrialization on the inlet. It’s working with the B.C. government to establish new water quality objectives, and also agreed to a stewardship plan with the province to restore the Indian River (xʔəl̓ilwətaʔɬ) watershed.

George said they want to bring back the balance their people maintained for thousands of years through stewardship. For example, fishermen would only take male chum at river weirs to ensure eggs would be laid, a measure not taken by commercial fisheries.

“We really did it as a management system, a way of keeping this balance within ecosystems and understanding we can only take so much,” George explained. “We knew our family needed this much to eat over the winter — not too much more, not too much less.”

The worldview was summarized by former elected səl̓ilwətaɬ Chief Leonard George, who is quoted in the study as saying in 1997 that “Your first father … learned from all of the animals in the environment around him.”

“He learned from the salmon the cycle of life and the highways of the ocean and why they would go out and the times they did and why they would return. He learned from the bird when the berries were ripe on the top of the mountain.”

Cultural knowledge was integral to the research process of accurately reconstructing the Tsleil-Waututh ancestral diet, because not all food remains are preserved in the archeological record.

Sockeye salmon were processed on the spot at the Fraser River, and so didn’t leave evidence in Burrard Inlet to signify their importance as a staple cultural food, George said. Shell middens preserve well, but plants don’t. Deer bones also preserve well, while octopus and sea cucumbers don’t leave archeological traces. Efford relied on cultural knowledge from people like George and her father to fill the gaps of the story told by the soil.

“The Tsleil-Waututh knowledge, the archeology, the historical record and the contemporary ecology — they were all weighted equally,” Efford said.

Efford added there’s an effort to shift archeology to serve communities, rather than take “without consent or knowledge” as archeologists have historically done.

When the research team ran its first computer simulation, Efford said she got emotional.

“It not only feels like you’re doing something interesting, but it makes it feel like archeology is doing something good after it’s been a tool for bad for so long,” she said.

George agreed that for a long time, academia observed Indigenous Peoples and made assumptions without their input, extracting value from communities rather than adding it. She was happy the collaborative approach meant Tsleil-Waututh knowledge was accurately represented in the study.

“We’ve always been here, this is our way of life and how we manage things. This just put that scientific bow on it.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...