5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

In January, Craig Comstock did what he’s done many times over the years — loaded his two dogs into his vehicle and drove from his home in Calgary to the backcountry for a day hike.

Comstock, 44, is an avid outdoorsman — he hikes, fishes and hunts pheasants and partridges — but none of that prepared him for what he found in the bush.

First, he came across two dead foxes and a dead wolf.

“Their heads had been cut off, their feet had been cut off and they had been skinned,” he told The Narwhal, noting that he also saw “several piles of bait meat.”

Then, as he walked on, he felt the prickly sensation of being watched. His eyes met those of a wolf, just 10 metres away. It was huge, he said — much, much bigger than his own dogs.

He froze.

Then he noticed that the wolf was trapped in a wire snare. Comstack and the wolf stared at each other.

“I wish there was something I can do to help,” Comstack remembers thinking.

“I can’t cut you loose, buddy,” he thought.

The wolf lay back down in the snow.

Comstock would find six other dead wolves caught on the same trapline.

When John Marriott, a local wildlife photographer and conservationist in Canmore, Alta., first heard word about the live wolf found in a snare, he set out to check the traplines himself.

What he found, he says, was a “scene of carnage.” He told The Narwhal he found three dead wolves, nine dead coyotes and four dead foxes — all of which had been skinned.

All, he says, were “just laying there with the meat in various stages of decomposition.”

Craig Comstock came across several skinned dead animals on a recent hike along the front ranges of the Rocky Mountains. Photo: Craig Comstock

Comstock says he found several piles of bait meat near the decaying bodies of skinned wolves on a recent hike along the front ranges of the Rocky Mountains. Photo: Craig Comstock

Comstock and Marriott’s findings are just a small part of the annual wolf kill in Alberta, but wilderness advocates fear recent similar killings may have all but wiped out two of the three wolf packs whose home territory is largely inside Banff National Park.

When wolves leave the protection of the park, they are fair game for hunters and trappers — a practice scientists and advocates say is threatening the park’s ability to protect the wide-ranging species that call it home.

Alberta has no restrictions on baiting wolves for trapping on public lands, including right next to national parks.

Parks Canada confirmed to The Narwhal last week that in recent months a trapper killed two radio-collared wolves just outside of Banff National Park, saying there is “anecdotal information” that 11 wolves have been killed in total, a number that can’t be confirmed until the spring.

Jesse Whittington, a wildlife ecologist with Parks Canada, told The Narwhal that the two wolves were killed by the same trapper less than a kilometre apart, just six kilometres outside of the boundary of Banff National Park. A third radio-collared wolf hasn’t been seen since December and may have been baited and trapped as well.

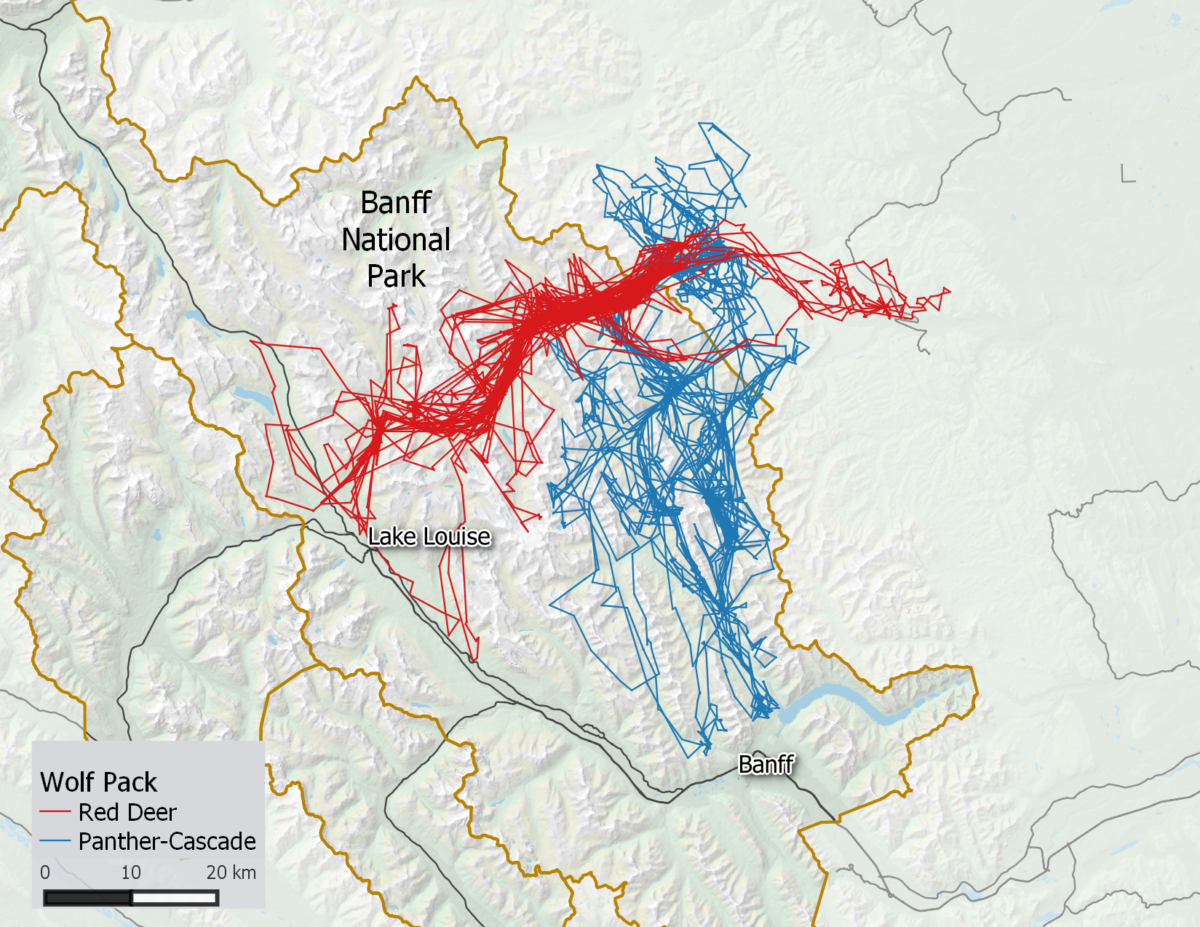

The movements, starting in February of 2018, of two radio-collared wolves in the Red Deer and Panther-Cascade packs. Both wolves were eventually trapped and killed just outside of the boundary of Banff National Park. Image: Parks Canada

Three wolf packs travel in Banff National Park as part of their home territory: the Cascade-Panther, Red Deer and Bow Valley packs. Wolves naturally recolonized the Bow Valley area in the 1980s, having been driven out of the park entirely roughly 30 years earlier.

According to Marriott, 11 wolves were killed by the same trapper just outside of the park boundary, on public land.

Wolves can legally be hunted on public land by anyone with a licence to keep livestock on that land at any time of the year, but trappers must stick to the trapping season (winter) and are often after pelts.

Marriott says trapping these particular wolves has significantly depleted the population of wolves that roam through Banff National Park. The Red Deer pack consisted of eight wolves at last count in December; the Cascade-Panther pack had just one wolf remaining.

“Whether there’s still one wolf left in [the pack], or whether they’re gone altogether, nobody really knows at this point,” Marriott says.

“But given the number of wolves that the trapper has taken out, there’s a really high likelihood that the pack is just gone altogether.”

Wildlife photographer John Marriott often captures images of wild wolves in Banff National Park, but on a recent outing he found a “scene of carnage.” Photo: John Marriott, wildernessprints.com

Marriott advocates for buffer zones to be established around the periphery of national parks, to limit the hunting and trapping of wide-ranging species.

Mark Hebblewhite, a professor of ecology at the University of Montana, told The Narwhal by email that buffer zones have been established outside other parks. “Yellowstone and Glacier Parks in Montana have established zones outside of their national parks with a reduced quota of two wolves that can be trapped,” he noted.

“This policy was adopted by Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks to specifically reduce negative effects of trapping on Yellowstone and Glacier.”

But no such buffer zone exists around Canada’s Rocky Mountain national parks, and trappers and hunters can often collect financial rewards in the form of bounties for their kills. (A Parks Canada communications representative did not respond to a question about buffer zones by press time.)

“Parks Canada requires that parks are managed for ecological integrity,” Jodi Hilty, president and chief scientist of the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative, told The Narwhal.

“Most national parks are too small to really sustain populations like wolves by themselves so parks really need to think about how adjacent lands and activities can inadvertently affect ecological integrity in parks.”

A 2002 study on wolf mortality in Banff National Park found that humans were responsible for three quarters of wolf deaths between 1987 and 2001 — and 67 per cent of those deaths were from hunting and trapping outside the park’s boundaries.

The study cites the “edge effect” of protected areas as being largely responsible for wolf mortality.

“It’s generally accepted that it’s good to have buffer zones of less human disturbance and pressure on wildlife around core protected areas,” Carolyn Campbell, conservation specialist with the Alberta Wilderness Association, told The Narwhal.

At 6,641 square kilometres, Banff National Park encompasses a large portion of Alberta’s Rockies — part of the Yellowstone to Yukon wildlife corridor and crucial habitat for wide-ranging species which require ample habitat to find food and mates.

“It’s an enormous park,” Marriott says. “But it’s still is not big enough to protect very many wolf packs from the persecution that they face as soon as they leave the protected areas.”

Wolves can range over an area up to roughly 2,600 square kilometres according to the United States Fish and Wildlife Service. A 2002 study in Banff found wolves’ average home range is 1,709 square kilometres.

“For these wider-ranging species where the park is not big enough to protect them…there really needs to be a bigger zone where they are protected from hunting and trapping,” Marriott told The Narwhal.

“Wolves, cougars, lynx, bobcat, wolverines — all of those animals are still either trapped or hunted if they step one foot out of a national park.”

Whittington echoed that risk. When “wolves travel outside of the park, they’re at risk of hunting and trapping,” he said.

“They spend 80 per cent of their time in Banff National Park,” he said. “But when they travel out of the park they encounter… different hazards.”

Whittington noted that wolves travel in tight packs in the winter. When a tight pack of wolves is drawn to an area — they are often baited — and encounters a trap line, many wolves may be trapped all at once.

“If all the animals are traveling together,” Whittington said, “they have a higher risk.”

Bait hanging as part of a neck snare near the spot Craig Comstock found several wolf carcasses while on a hike in January. Photo: Craig Comstock

The wolf packs that mostly travel in Banff National Park are small.

In December, the Red Deer pack had eight wolves, Whittington of Parks Canada said. One of those wolves — a breeding female — is among the two confirmed to have been trapped and killed. Another wolf in the pack was radio-collared, but that wolf hasn’t been spotted since December, when it was captured on remote camera.

And in the Panther Pack, after the death of the other radio-collared wolf, there was likely only one wolf left in the pack.

Whittington told The Narwhal that Parks Canada will not be able to confirm “anecdotal information” that 11 wolves have been killed until the spring, when park staff can check remote cameras and estimate the populations.

“It can be difficult to keep tabs,” Whittington said. “When wolves are caught in snares, we’re not notified.”

“Certainly trapping is a common cause of mortality in the eastern slopes,” he said.

Marriott says he confirmed with a representative of the Government of Alberta that 11 wolves had been killed on one trapline just outside of the park so far this winter. Reached by email, Olav Rokne, a spokesperson for Alberta Environment and Parks, could only confirm to The Narwhal that 11 wolves had been reported as killed by trappers in the larger trapping area since the start of the trapping season.

Rokne noted that trapping records showing the number of wolves killed will not be released until the end of the trapping season in the spring.

The Narwhal attempted to contact local trappers and outfitters, but did not receive a response.

A wolf pack spotted near the town of Banff. Photo: John Marriott, wildernessprints.com

According to Rokne, there are roughly 7,000 wolves in the province.

“We are seeing signs of growing populations of wolves provincially,” he noted by email. “Many of these animals are being observed on settled portions of the landbase.”

Wolves are not listed as a species at risk in Canada, though some populations in the U.S. are classified as endangered or threatened. Wolves were first protected under the federal Endangered Species Act in the U.S. in 1973.

“Canada has no such designation for the wolf despite the fact that it has been extirpated from much of its former habitat,” according to the Alberta Wilderness Association.

An average of 700 wolves are trapped and killed annually in Alberta, Rokne said. On average, 52 wolves are killed adjacent to Banff and Jasper each year.

Many fur-bearing animals are trapped for their pelts. In the 2016/2017 season, 823 wolf pelts were sold according to data from the Alberta Trappers Association — each fetched an average of $146.09.

A trapper can obtain a fur management licence — a licence to trap — for around $40. Many trappers and outfitters bait their traps with meat to attract predators.

While trapping has long been a way of living off the land for some Indigenous people, it has also become popular with tourists, with some guide outfitters offering baited “trapline adventures” for $3,500 or combined wolf hunts and trapline adventures for $6,950. As one guide outfitter website puts it, “a wolf [is] one of the most sought after trophies in the world.”

Alberta does not put limits on the number of wolves a trapper can kill in a season, and “individual trappers are not subject to a quota on wolves,” Rokne of the Government of Alberta said in an email, adding that the province monitors the overall wolf population and the annual harvest.

Currently, he said, the province sees “no need to impose a quota.”

Trapping is allowed on much of Alberta’s public land, including in most provincial parks, according to Rokne. There is no limit on the number of wolves that can be trapped adjacent to national parks.

On the province’s trapping regulation website, a message from Minister of Environment and Parks Shannon Phillips reads, “Trappers play an important role in helping manage Alberta’s furbearer populations and minimize human wildlife conflict related to furbearers.”

The Alberta Trapping Association (which did not respond to request for comment) writes

on its website that, “when it comes to wildlife management, trapping is right up there with hunting as far as effectiveness and necessity for the promotion of local ecosystems and population maintenance.”

But the Alberta Wilderness Association’s websites notes that “wolves play a valuable role in keeping wild ecosystems healthy.” Wolves are considered a keystone species, meaning their presence is essential for the functioning of a healthy ecosystem.

Campbell of the Alberta Wilderness Association told The Narwhal the association respects the work some hunting and trapping groups do in habitat conservation, but also notes that “wolves are really valuable top predators.”

A lone black wolf in a winter snowstorm. Photo: John Marriott, wildernessprints.com

Government regulations require that non-killing snares need to be checked every 24 or 48 hours depending on the type of licence, meaning animals can legally be left for up to two days.

But advocates worry that animals are also left to struggle in neck snares that are supposed to kill animals immediately, sometimes strangling to death over hours or even days. Marriott recently documented these concerns in an episode of his video series, Exposed.

The Alberta Trappers Association makes it clear on its website that it does not condone the suffering of trapped animals.

The association concedes that “larger predators like wolves, coyotes, lynx and foxes are usually taken in live-holding traps,” noting that devices that kill such large animals immediately “would be dangerous to use.”

But it also claims that, “the specialized and extremely-regulated traps were designed with the animals in mind. As many as 90% of all trapped animals in Canada are killed instantly.”

“It is imperative that we do not let radical animal-rights extremists ruin the image of such a beneficial practice,” it states.

Devices like killing neck snares are considered in Canada to be “non-commercial” devices, and are therefore not subject to the Agreement on International Humane Trapping Standards, which dictate that an animal trapped in a killing device should be “irreversibly unconscious” in less than five minutes.

Marriott said he’s seen a wide variety of species caught in traps — wolverines, cougars and others. He’s concerned that national parks are supposed to be protecting wide-ranging predators, but with trappers set up on their peripheries, possibly with heaps of bait, the animals face significant threat.

“When you consider this is a UNESCO world heritage site, it’s supposed to be the No. 1 priority of Parks Canada to protect the ecological integrity of the park,” Marriott said.

“But if they’re not getting any partnership with agencies working outside of the park, you can see that wide-ranging predators like wolves really have no chance.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...