Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

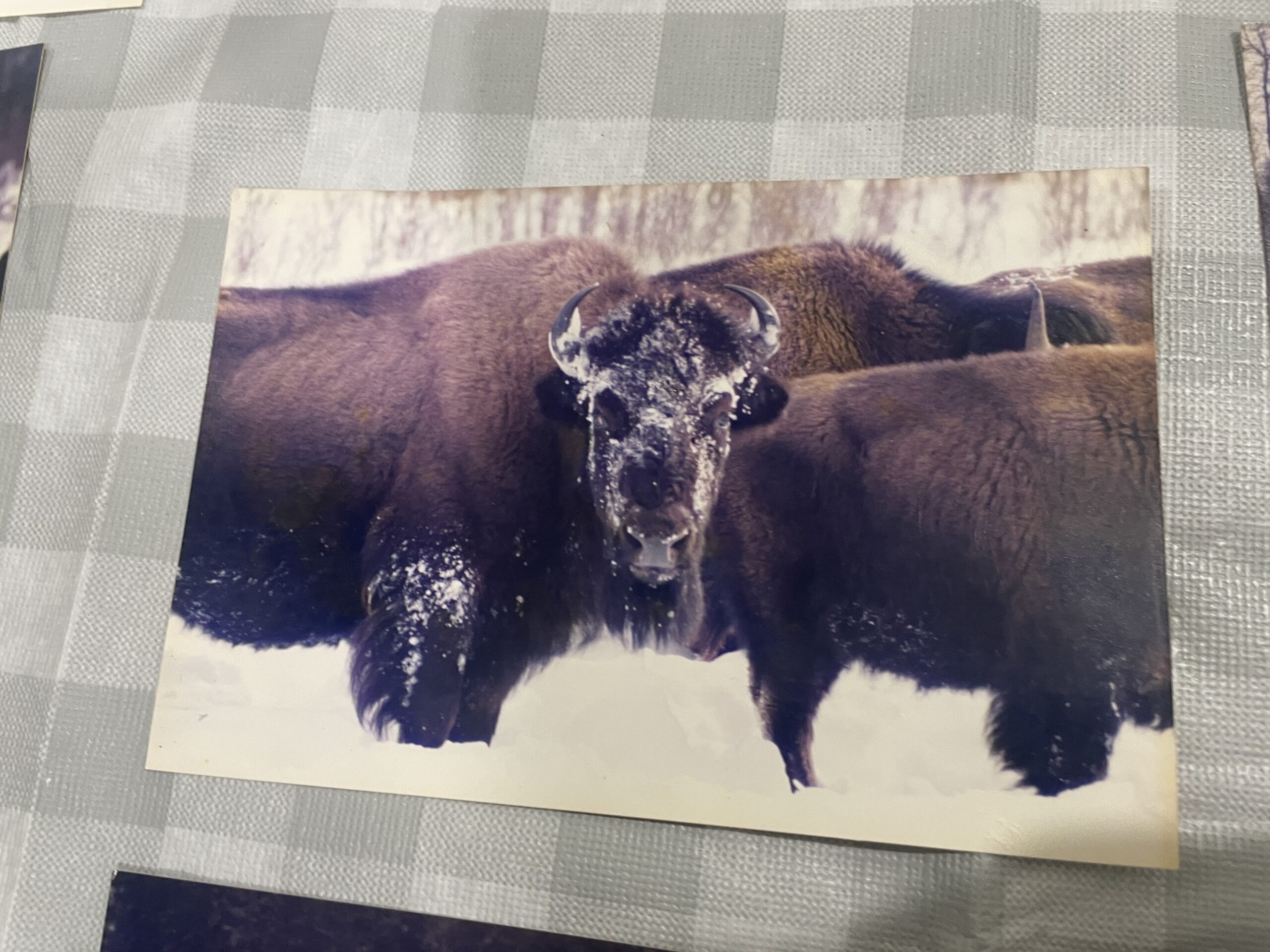

A unique wood bison herd near Wood Buffalo National Park in northern Alberta is on the verge of being wiped out.

The herd, one of only two naturally established disease-free herds in Alberta, has as few as nine bison remaining. With logging set to begin in the area imminently, community members are concerned it will have dire consequences.

Federally, wood bison are considered a threatened species, but the Wabasca herd is stuck in a sort of regulatory limbo as the federal and provincial governments work to identify its critical habitat — a step that would bring protections through the Species At Risk Act.

Indigenous Knowledge Keepers insist both orders of government don’t have a proper understanding of the herd’s range and are using incomplete information to judge risks and territory.

The herd received a classification that prevented further unregulated hunting in 2021, but since then no further steps have been taken to reduce its steady decline.

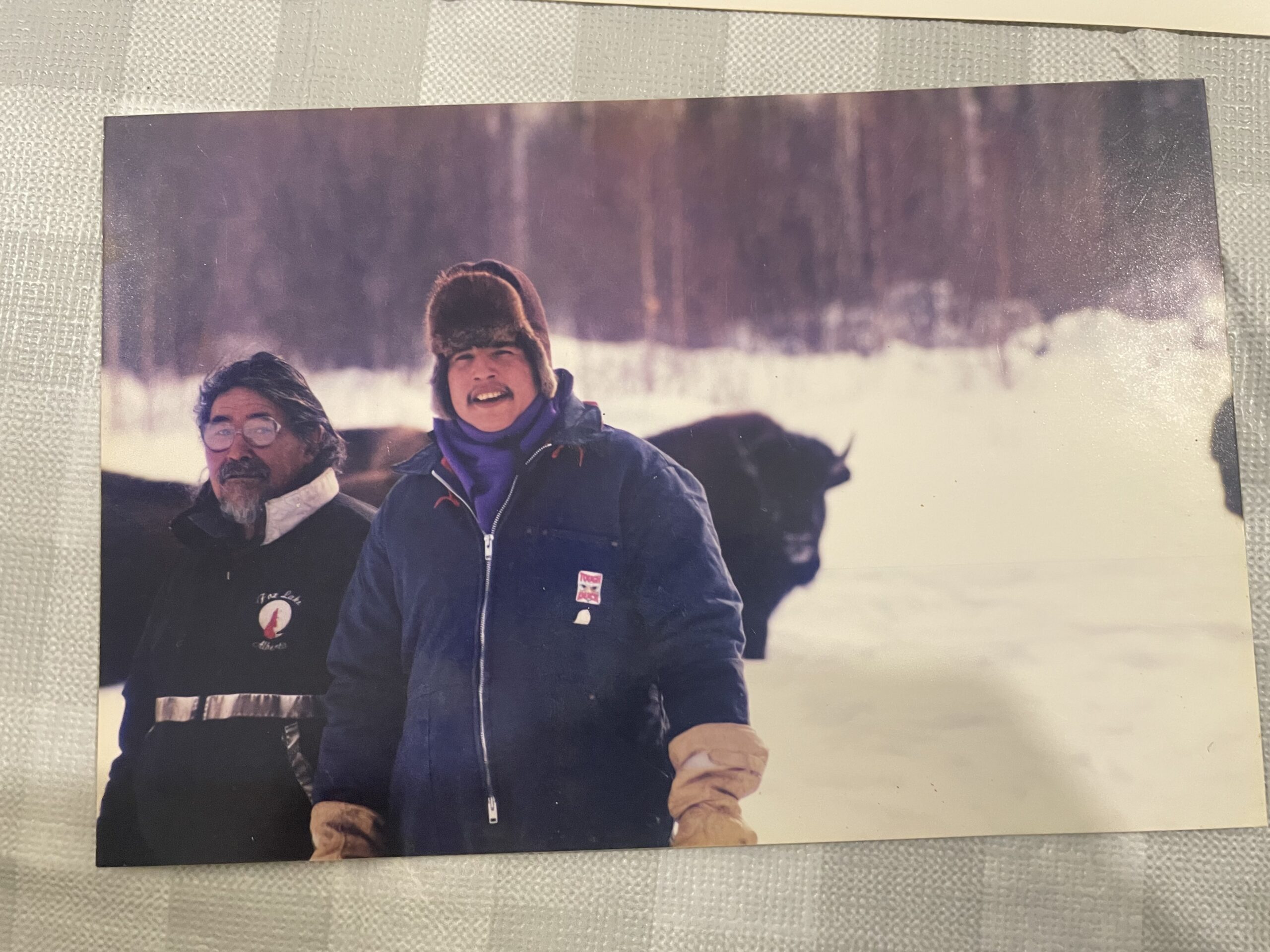

Johnson Alook, a trapper in the area and a member of the Little Red River Cree Nation, says he used to see buffalo everyday when they were out trapping, but now they can’t find them even when they try to track them.

He and others from the community formed a group called ShagowAskee — roughly translated as “untouched forest” — to push for more protection for the herd. ShagowAskee is calling for a three-year moratorium on logging in the area to take pressure off the bison and come up with a plan for moving forward.

So far, those efforts have been fruitless.

“We’re trying to protect the buffalo for ceremonial rites and for our future generations,” Alook says.

The Wabasca herd, along with the nearby Ronald Lake herd, are the only wood bison in Alberta that are in their natural habitat and which do not have the diseases common to other herds — tuberculosis and brucellosis.

Unregulated hunting, habitat pressures and even predation have reduced the herd’s numbers to a point where one bad winter could eliminate it, according to a federal threat assessment.

Between 2011 and 2014, at least 15 of the bison were killed by the government to confirm the herd was disease-free. Members of ShagowAskee, as well as the federal wood bison recovery strategy put the figure at 24.

Another herd, the Hay Zama in the northwest of the province, is also disease-free and free-ranging, but was introduced to the area as part of a repopulation plan.

It is estimated there were 168,000 wood bison in Canada in the early 1800s, but that number plummeted to a few hundred by the end of that century. More recent estimates from 2015 indicate there are just over 8,500 free-ranging wood bison in the country, slightly over half of which are disease-free.

“The recovery of wood bison as a species hinges on the survival of these two small herds, because their genetics are so different than anything else in the province,” says Gillian Chow-Fraser, the boreal program manager for the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, which has been working with ShagowAskee.

The Ronald Lake herd has had more government attention than the Wabasca herd. The province established the Kitaskino Nuwenëné Wildland Park in a portion of its range and issued a moratorium on crown mineral rights in the part of its range which falls outside the park.

The province is also working with First Nations to monitor the health of the herd, which currently sits at approximately 270 members.

Wabasca, on the other hand, has no protection beyond the recent prohibition on hunting.

The Wabsaca herd is located near the western edge of Wood Buffalo National Park World Heritage Site, an area itself threatened by a multitude of industrial uses, according to UNESCO. The organization has recently launched an investigation into whether the site should be officially designated as “in danger,” citing risks including Alberta’s oilsands, where tailings ponds have been found to be leaking.

Logging historically took place within the park’s boundaries but is now focused outside the park — including in the range of Wabasca bison herd.

Logging is now set to start on the southwest edge of the Wabasca range, an area that Alook and members of ShagowAskee say will impact critical bison habitat, but which the B.C.-based logging company Tolko — and the provincial government — say is outside their range and won’t affect the herd.

The company is building a winter road and harvesting is imminent.

Members of the group met with officials from the government on Jan. 9 to ask for a stop to the logging, but walked away with only the promise of more conversations. That meeting followed a letter they sent on Nov. 3, 2022, which shared new information about a breakaway group of 10 to 15 bison nearby — what they call the Ghost herd.

“We are aware that Tolko’s imminent harvesting plans will directly impact both the Wabasca herd and the Ghost herd,” the letter said.

A federal Imminent Threat Assessment in 2020 pointed to logging as a potential threat to the Wabasca herd in the long term, but said current logging plans out to 2026 would not have an impact. That information did not include ShagowAskee’s information on a breakaway herd.

The group says it was reluctant to reveal the presence of the Ghost herd but felt it was necessary to share the information with Tolko and the government.

Sugu Thuraisamy, the managing director of ShagowAskee and a registered professional forester in Alberta, says the logging activities on the western side of the Wabasca range will push the animals to the east, bringing them closer to the diseased herds in and around the Wood Buffalo National Park and further shrinking available habitat.

He also says the volume of timber, from the perspective of the logging company, is small and Tolko has plenty of other areas it could log.

“This herd is particularly important to this community and the trappers,” he says. “Why can’t they just operate somewhere else, get the herd to increase in population size and then come back to the area when they’re healthy enough to survive?”

At the heart of the current standoff is the difference between what trappers say they know from being on the ground and what the company and the government acknowledge.

“Tolko has committed to shift the harvest if any bison are spotted in the area, and so far, none have been identified,” Chris Downey, a communications advisor with Tolko, said by email.

“We appreciate the ShagowAskee group continues to keep us informed regarding the bison and their potential location, but we have not found any in the harvest area. There are other nearby areas where the bison may have relocated, including a protected region to the north of our harvesting area.”

The company did shift some of its planned activities based on information from ShagowAskee, according to Thuraisamy, but says it’s not enough to protect impacts on the herd.

Leanne Niblock, communications director for Alberta Forestry, Parks and Tourism, said the government was “not aware of additional wild wood bison herds or new populations outside of the currently identified provincial bison ranges.”

“Alberta’s previous discussions with the ShagowAskee Foundation have provided information valuable to Alberta’s bison recovery efforts, and the department will discuss the need to adjust future harvest plans with forestry operators as new information about potentially unidentified bison populations becomes available,” she said by email.

Thuraisamy said the federal government has told them they recognize the importance of the Wabasca herd and the Ghost herd and has asked the group to do more work on sharing Traditional Knowledge on the herds’ range.

A spokesperson for Environment and Climate Change Canada said management of bison and regulation of forestry is a provincial matter and it could not comment.

Alook has been trapping his whole life, more than 40 years, and has seen the animals disappear and the forest change as industry moves in and the bison population dwindles. He points to one area he used to trap and says it was once covered in pine trees, but since logging, it has been taken over by aspen.

“I’m on the ground all the time. And I track the buffalo,” he says “We’re trying to tell them this is what we know, but don’t think they’re listening to our knowledge.”

He and the rest of ShagowAskee want the province and the federal government to establish what they say would be a more realistic — and larger — range for the Wabasca habitat.

It’s something Chow-Fraser, with Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, supports.

“It absolutely is [to] the benefit of these industrial players to have these very small habitat boundaries for species at risk. And also, as a herd gets smaller and smaller, that area of occupied habitat gets smaller and smaller and so then again, you kind of benefit off of the disappearance of the species at risk,” she says.

“As they get smaller and smaller, the magnitude of those impacts becomes greater. And so really, that area should increase.”

Alook traces a long line all the way back to the 1800s when wood bison were decimated and says that is still ongoing. He says someone has to speak for the bison and, in the process, protect the rights of his people.

“We have Treaty Rights — we can trap, hunt and fish,” he says. “But if there’s no trees, then our trapping rights are over.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...