Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Following intense pressure from local residents to do something about their community’s deteriorating drinking water, the mayor of the Okanagan community of Peachland has called on the provincial government for a “time out” on further logging of local watershed lands.

The request by Mayor Cindy Fortin was made in writing to Doug Donaldson, Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development one month ago, and flagged the community’s ongoing concerns with logging impacts on drinking water quality.

The letter only recently become public.

For years, Trepanier and Peachland creeks, the two creeks that Peachland residents rely on for their water, have been contaminated by fine particles of dirt that can mask potentially deadly pathogens, making the water unsafe to drink.

Many community residents believe that accelerated logging of the forests in the community’s watersheds caused their drinking water to become unsafe. As detailed in a recent investigation by The Narwhal, Peachland’s water grew markedly worse in the last decade and reached its lowest point in 2017 and 2018 after a mudslide below a logging road blocked Peachland Creek.

As a result, the community is now spending an estimated $24 million on a new water treatment plant and related infrastructure that many hope will be up and running in about one year’s time. Until then, local residents, like their counterparts in numerous other communities in the Okanagan region, live with the prospect of frequent boil water advisories.

Peachland’s main water supply comes from Peachland creek, its muddy waters seen here flowing into Okanagan Lake. Photo: Will Koop / The Narwhal

Until recently, Fortin was reluctant to speak out forcefully on the issue, saying that a logging moratorium was too “lofty” a goal.

But recent presentations to council appear to have swayed her thinking. On June 26, she wrote to Donaldson asking that he halt the issuance of any new logging permits in the forested valleys that drain toward the community’s water intakes “so that the cumulative impacts on water quality, quantity and flow can be thoroughly examined.”

“This is huge. This is a big step,” said Taryn Skalbania, one of the community’s most vocal advocates for watershed protection and co-chair of the Peachland Water Protection Alliance. While Skalbania said the mayor’s letter falls short of what is needed, it is an important first step and may serve to motivate others in smaller rural communities like Glade and Grand Forks, which have also been the focus of investigations by The Narwhal, and where tensions run high over existing or proposed logging of watershed lands.

Taryn Skalbania stands in front of the Deep Creek Water Treatment Plant on McDougald Road in Peachland. A landslide occurred five mins off of McDougald Road and disrupted Peachland Creek, the town’s primary water supply. Photo: Travis Oleniak / The Narwhal

In response to calls from The Narwhal, Fortin said she understands the forest industry is important to the economy of the province, but that it has come at a steep price for her community.

“There’s been a lot of it. It almost seems like an increase in logging over the years,” Fortin said. “We’re not against forestry. We understand the economy of it and why it’s important, especially to the entire province. But it’s just that so much is happening up there that we’re really concerned that the cumulative effects are going to impair and affect our water. And we just can’t let that happen.”

Keith Fielding, a former mayor of Peachland and a current councillor, said the community is not alone in finding itself in a terrible bind when it comes to watershed lands.

In almost all cases, those lands are Crown or publicly owned and fall under the provincial government’s jurisdiction, not nearby communities. Communities have little or no say on the pace or kind of logging, yet are on the hook to pay for upgraded water treatment facilities in the event that logging or other land uses such as mining or cattle grazing degrade their water supplies.

“That is a problem. Especially for small communities that are faced with very large expenses for having appropriate drinking water. The standards are very high and are set by the health authority,” Fielding said. “And there is very little that smaller communities can do other than either look for government funding to build the necessary treatment plants or to plan for it (proactively building such plants) for a long period of time.”

Fielding, who worked for the City of Toronto until retiring and moving west 20 years ago, said Peachland always intended to build a water treatment plant. But the steady deterioration of the community’s water essentially forced the issue. Now, he says, the big problem is what happens if the water entering the new treatment plant continues to be muddy for months on end or gets even worse.

If watershed lands continue to be “denuded” by logging, he says, more water will run off logged lands faster, carrying more sediment with it.

“What we don’t want is for any problem to be exacerbated by additional, unwanted runoff,” Fielding said. “It just makes it worse, and it makes it more expensive for the water treatment plant to operate.”

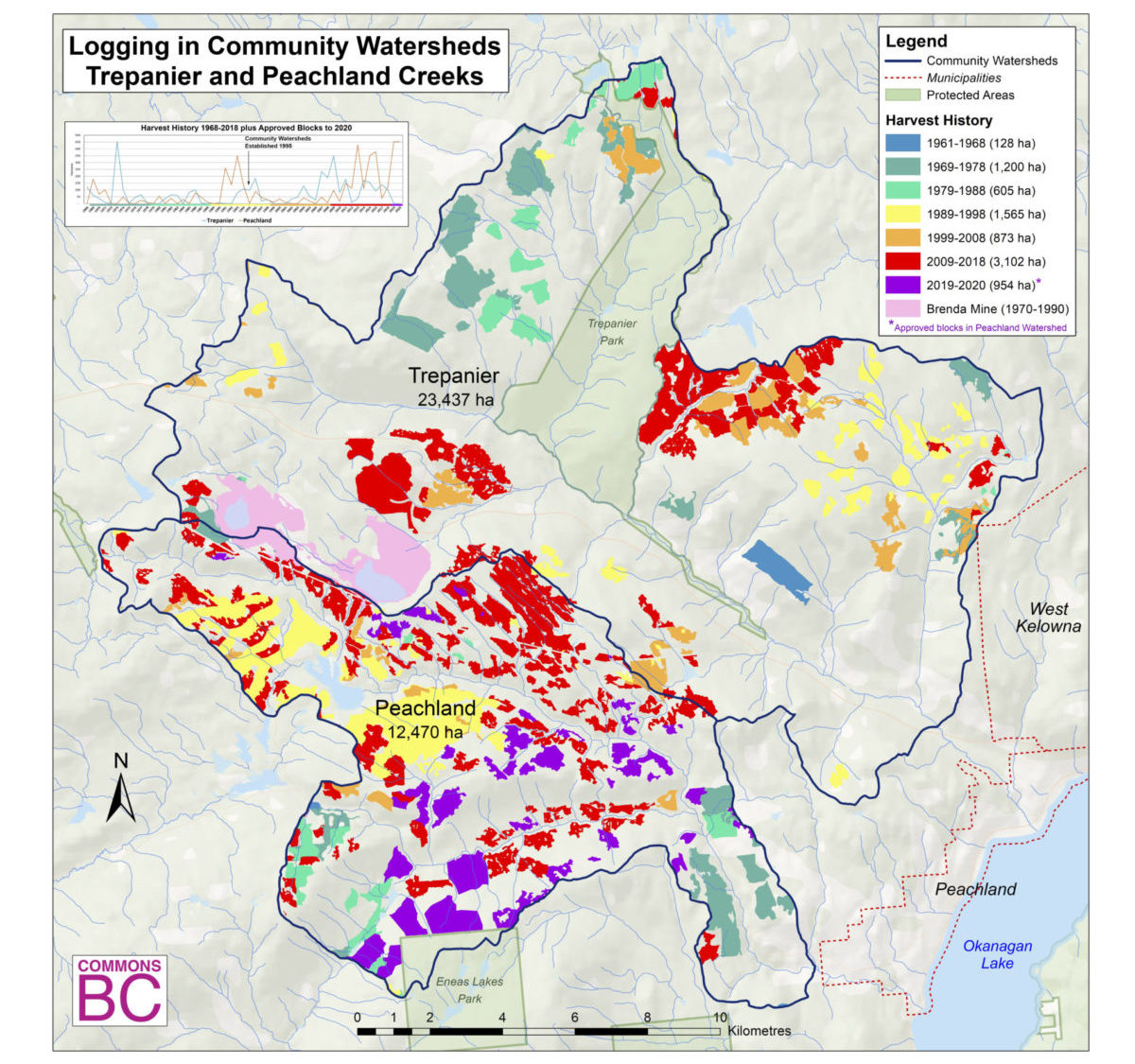

Cumulative logging activities in Peachland’s watersheds have degraded the quality of drinking water. Map: Dave Leversee

Work done by the Peachland Water Protection Alliance and submitted to Peachland’s council prior to the damaging 2017 landslide noted that clean water ranked as the “number one issue for residents” and that nearly three in four of residents polled “wished for consistent, improved quality and quantity of water.”

In a June 27, 2017 request to Peachland’s council, the alliance noted that at that time the district faced spending $18.8 million “on the first phase” of a water system improvements that carried a combined price tag of $55 million.

“The district’s own website supports the Interior Health Authority’s recommendations that it is safer, cheaper and easier to protect water at its source, the watershed, than to treat it later at the plant intake,” read the request, signed by the alliance’s chairman, Joe Klein.

While Skalbania welcomed Fortin’s intervention, she said more specific things need to be demanded of Donaldson’s ministry.

She noted that in the current five-year planning period as many as 1,000 hectares more forest — the equivalent of two-and-a-half Stanley Parks — could be logged in Peachland’s watersheds. In addition, another 55 kilometres of logging roads could be built on watershed lands.

In a news release, the alliance said it “wholly supports” the mayor’s call for a pause in logging and said that current logging plans “will destroy much of what is left” of the community’s watershed lands.

“Already, more than 40 per cent of Peachland’s watershed is or ‘acts as a clearcut’ — meaning that past clearcuts have been replanted but that hydrologic recovery is only beginning,” the news release states.

Ray Travers, a retired professional forester and long-time provincial civil servant, is quoted in the release saying it’s time for the provincial government to act boldly and to consider special zoning of community watershed lands “to protect water and non-timber resources, similar to zoning already used in urban areas such as ALR (the provincial Agricultural Land Reserve) for farmland.”

The Narwhal filed several questions with Donaldson’s ministry.

Jeremy Uppenborn, a senior public affairs and media relations officer with the ministry, said the ministry had not yet received Fortin’s letter.

In an email, Uppenborn said that logging will likely continue on watershed lands.

“The province doesn’t plan to suspend harvesting approvals where proposed developments are consistent with legislative requirements, higher level land-use plans and professional assessment recommendations,” Uppenborn wrote.

Asked how the ministry plans to address cumulative impacts, Uppenborn said that a “hydrological assessment” of Peachland’s watersheds was carried out for the ministry by a “professional engineer” and that that report indicated “proposed” logging developments “were not considered to carry any major risk to water quality.”

Three companies currently have logging rights in the watershed, including Tolko, Gormon Bros. and the Westbank First Nation-owned company Ntityix Resources. Blocks of forest are also auctioned for logging in Peachland’s watershed under the auspices of BC Timber Sales, a provincial agency.

This article was produced in partnership with the Small Change Fund.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...