What’s scarier for Canadian communities — floods, or flood maps?

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

If you were to take a walk through the Clack Creek forest, a 24-hectare hotbed of biodiversity criss-crossed by well-used trails, you’d find more than 1,000 felted hearts stapled to the bark of towering trees.

The hearts are meant to symbolize the hope of the local community that Clack Creek will remain the heart of an expanded Mount Elphinstone Provincial Park — and not a logging cutblock.

But, despite numerous objections from the Sunshine Coast Regional District, a legal challenge and predictions of a renewed war in the woods from the conservation group Elphinstone Logging Focus (ELF), the trees are about to fall.

BC Timber Sales deferred placing the Clack Creek forest cutblock up for auction in 2014 “due to information about at-risk species, destruction of a historic trail, blowdown issues, habitat for Elk and coastal-tailed frog we and mounting public pressure,” Elphinstone Logging Focus told The Narwhal. Photo: Elphinstone Logging Focus

Felted hearts have been placed around the Clack Creek forest, slated for logging any day now. The group Elphinstone Logging Focus claims the area might be B.C.’s most contentious cutblock, after being deferred four separate times by various BC Timber Sales Managers. Photo: Elphinstone Logging Focus

In May, BC Timber Sales, the provincial government agency responsible for auctioning off 20 per cent of the province’s annual allowable cut of timber to the highest bidder, awarded a logging contract to Black Mount Logging of Squamish to cut 29,500 cubic metres of timber around Clack Creek.

The contract shocked the local community. Supported by information in an ELF-commissioned report by conservation biologist Wayne McCrory, community members hoped to work with the province and Sechelt (Shishalh) and Squamish First Nations to link the three tiny disconnected islands that make up Mount Elphinstone Provincial Park.

” … the current park areas will likely become islands of extinction over time.”

The three patches of existing park cover 139 hectares, but the vision of local residents and the Roberts Creek Official Community Plan is to expand the park to 1,500 hectares. Much of that unprotected area is already used for recreation and is home to animals such as Roosevelt elk and colonies of rare plants.

“If the entire Mount Elphinstone study area is not fully protected, the current park areas will likely become islands of extinction over time,” McCrory warned in the report.

Clack Creek, on the Sunshine Coast above the residential area of Roberts Creek, has a fiery history that saved it from previous clearcutting and has resulted in a naturally regenerated, low-elevation mature forest that shelters endangered species such as coastal tailed and red-legged frogs and the rare native snow bramble.

“It’s a serendipitous combination of fire and logging history that left this area intact in the 1860s,” said Ross Muirhead, ELF forest campaigner, quoting from a Federation of B.C. Naturalists conservation report.

In the 1860s, after logging began in surrounding areas, a catastrophic fire destroyed the Clack Creek forest, leaving only large fire-resistant Douglas firs. But, over the years the forest naturally regenerated.

Hans Penner, left, and Ross Muirhead from Elphinstone Logging Focus. Photo: TJ Watt / Ancient Forest Alliance

The Clack Creek forest is renowned for its biodiversity and, in particular, its abundance of more than 160 mushroom species. Photo: TJ Watt / Ancient Forest Alliance

Chanterelle mushrooms in the proposed expansion area of the Mount Elphinstone Provincial Park. Photo: TJ Watt / Ancient Forest Alliance

“That’s the beauty of it. It has the whole cross-section of plants and animals,” said Muirhead, pointing to a report that identifies 165 species of mushrooms, believed to be the densest concentration of mushrooms in B.C.

The trees, which are about 150 years old, are not considered to be old-growth because they fail to meet the province’s criteria of 250 years, but McCrory’s report describes the forest as “emerging old-growth” and Muirhead noted that only nine per cent of the rare coastal western hemlock ecosystem is protected.

The same science-based rules that apply in the Great Bear Rainforest should apply in the Elphinstone area, Muirhead said.

“All the science shows this area should be protected,” he said, adding that demonstrations and blockades are almost inevitable if trees decorated with hearts are felled.

“Things can get really explosive round here,” he said.

“In particular, three elderly women have said to us directly that they’re prepared to go up there and get arrested. We don’t know if that will actually happen, but that’s the sentiment that is out there.”

Laurie Bloom, an organic farmer who has campaigned with Elphinstone Logging Focus for years to save the area, said only three per cent of the lower and upper Sunshine Coast is protected in parks and ecological reserves, whereas other forest districts in the province protect 15 per cent.

“So we’ve been cheated here,” Bloom said.

“We don’t have a lot left to protect. It’s pretty well gone at the lower elevations,” she said, pointing out that the only large parks are “mountain tops.”

McCrory’s report found the low-elevation forest is “most representative of the ecology of the Sunshine Coast” and acts as a “biodiversity corridor” for species on the move.

A statement from the province said there are 15,400 hectares available for recreation in the Sunshine Coast Regional District, including 12,200 hectares classified as provincial parks.

But Bloom countered that there is no significant lower elevation land “for our future, for our children to experience or for tourism.”

“It’s disrespectful to this community. They are ignoring the will of the public and the regional district … Really we are trying to protect tattered remnants here. It’s the best of the last,” Bloom said.

If logging goes ahead it will gut the centre of the park proposal, ending all connectivity between the protected parcels, and the community’s dream of at least one low elevation park will die, she said.

In 2016, the nearby Twist and Shout Forest was the site of similar protests and blockades, with a dozen people arrested and this is a similar flashpoint, said ELF member Hans Penner.

“We all expected a different result from the province after the NDP got elected,” said Penner, who believed the protection plans were supported by local NDP MLA Nicholas Simons and Environment and Climate Change Minister George Heyman.

“We thought we were on the right track and then, all of a sudden, they pulled right out,” he said.

Hans Penner in an area his group hoped would become part of an expanded Mount Elphinstone Provincial Park. Photo: TJ Watt / Ancient Forest Alliance

Although there are many logging contractors around the Sunshine Coast, no local outfits bid on the Clack Creek block, possibly because they knew how contentious it was likely to be, said Muirhead, who believes Black Mount Logging would be willing to swap Clack Creek for another block.

He questioned how the province could get full value with only one bidder.

Black Mount Logging did not return calls from The Narwhal.

A spokesperson for the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, said there are no provincial plans to expand the existing park and the Clack Creek parcel cannot be switched.

“The province can’t offer something different than what was auctioned, even if the current licence holder agreed to it as it would violate auction and contract law,” the spokeswoman said in an emailed response to questions from The Narwhal.

“Further, if the province switched the area and provided the licensee with a different area than what was auctioned, the province would have significant exposure in terms of litigation from others that may have bid if the new area was the one that was auctioned,” she wrote.

A recent setback for Elphinstone Logging Focus was the rejection of a petition to the B.C. Supreme Court asking for an order quashing the BC Timber Sales decision and for the issue of a timber licence to wait until completion of a land use planning process with the province and Sechelt Nation.

Reasons for the court’s decision have not yet been released.

The petition says Elphinstone Logging Focus is opposed to any logging in the proposed park expansion area during discussions about its future protection, but that the group would not object to logging in other parts of the Elphinstone area.

A ministry statement says BC Timber Sales has consistently worked with local stakeholders to meet community concerns and measures taken include adding new old-growth management areas, buffering important trails and placing additional setbacks on streams.

But Lori Pratt, chairwoman of Sunshine Coast Regional District, said there are concerns about the lack of consultation.

The regional district has objected to the sale of Clack Creek Forest at least four times since it was referred to the board by BC Timber Sales on the grounds that there needs to be extensive land use planning for the Mount Elphinstone area with the Sechelt and Squamish Nations before logging decisions are made.

However, the province indicated there is nothing more local government can do about the Clack Creek decision, Pratt said.

The Sechelt Nation previously objected to logging at Clack Creek, but has since withdrawn the objection. Calls to the Sechelt Nation from The Narwhal were not returned.

The RCMP arrested 12 individuals protesting logging in the Elphinstone region in 2017. Photo: Elphinstone Logging Focus

In 2016 and 2017 members of Elphinstone Logging Focus and the broader community constructed blockades and engaged in protest actions to prevent logging from taking place in a BC Timber Sales cutblock only one kilometre from the current Clack Creek cutblock. Organizers with ELF say they anticipate similarly strong response from locals when logging in the Clack Creek forest begins. Photo: Elphinstone Logging Focus

Pratt said another reason the regional district opposes logging in Clack Creek is the area’s proximity to the watershed.

“We have been supportive of having a hold on logging in that area. There’s the watershed and it is quite close to homes,” she said.

The possibility of a blockade is worrying, Pratt said.

“It’s not what we would like to see. There needs to be a better balance between the economy on our Sunshine Coast and environmental needs. Both sides need to be able to listen to each other and work through this,” she said.

“Of course the safety of all of our residents in the logging and the environmental industry is of the utmost importance to us. We just want everyone to be safe and minimize confrontation in the woods,” she said.

A statement from the forests ministry states rare plants will be protected and concessions on harvest rates have already been made. Following community consultations, blocks were dropped or converted into old-growth management areas and the size of the harvest area has been reduced by 30 per cent while wildlife tree retention areas have increased by 20 per cent, the ministry said.

The ministry “continues to assess the effectiveness of our approach to managing rare plant communities and will be presenting a report to the Forest Practices Board specific to Mount Elphinstone in the fall of 2019,” the statement reads.

“In recognition of the importance this area has to local residents, BCTS has reduced the average harvest rate to about 27 hectares per year on the south-facing slope of Mount Elphinstone — a rate of harvest approximately half of the rate the area can support,” according to the statement.

The licence will support local employment and provide more than $2 million in stumpage revenue, the ministry said.

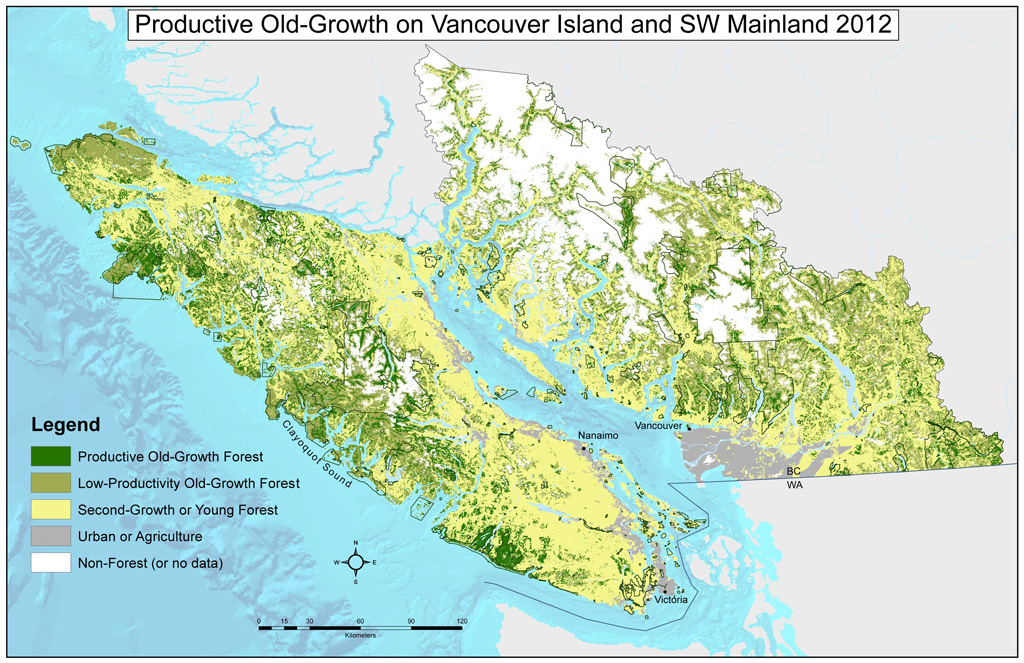

A map of remaining old-growth forest based on satellite data from 2012. Map: Ancient Forest Alliance

A map of pre-existing forests in Southern British Columbia. Map: Ancient Forest Alliance

BC Timber Sales has recently been at the centre of numerous controversies after approving logging in contentious areas such as the Nahmint Valley, Schmidt Creek above Robson Bight and the Skagit Doughnut Hole beside Manning Park, leading to calls for the agency to be treated as a stand-alone Crown corporation subject to independent investigations.

Provincial amendments to the Forest and Range Practices Act are likely to be tabled next spring and the provincial government has launched a new panel to gather feedback on old-growth forests.

A recent poll commissioned by Sierra Club BC showed that 92 per cent of British Columbians support taking action to save endangered old-growth forests.

Caitlyn Vernon, Sierras Club BC’s campaign director, said the climate crisis means the provincial government must put the brakes on rapid logging of endangered old-growth forests.

“We can protect big, old trees and have sustainable forest jobs into the future, but only if we act quickly to increase protection and improve forest management,” she said.

And on the Sunshine Coast, that would include recognizing the significance of emerging old-growth, Muirhead said.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

When maps showing areas most likely to flood are outdated, it puts people and property...

We’re suing the RCMP for arresting a journalist on assignment for The Narwhal. It’s an...

As glaciers in Western Canada retreat at an alarming rate, guides on the frontlines are...