Drawing (on) a decade of climate change in the North

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

If Canadians knew their own history, the National Energy Board hearings on the Kinder Morgan pipeline might not have been declared inadequate by the Federal Court.

The NEB failed to consider the impact on coastal waters and didn’t adequately consult Indigenous people, the court ruled.

Those errors could have been avoided if the NEB followed the model of the Berger Inquiry on the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline, generally considered the gold standard for such reviews.

In the early 1970s Canadian Arctic Gas Pipelines, a consortium including the world’s big oil companies, wanted to build a natural gas pipeline from Prudhoe Bay, Alaska, across the northern Yukon (near the village of Old Crow) to the Mackenzie Delta, then south along the Mackenzie River Valley and through Alberta to the United States. It was to be the longest pipeline ever built and the most expensive private construction project in the world.

A solar array in the village of Old Crow. Photo: Matt Jacques / The Narwhal

The federal government, led by Pierre (not Justin) Trudeau, felt there had to be adequate consultation with the people who would be affected by the construction of this vast project.

On March 21, 1974, Justice Thomas R. Berger of the B.C. Supreme Court was appointed to head a royal commission. Berger was a former NDP MP from B.C. and had been both an MLA and led the provincial New Democrats. Perhaps more importantly, as a lawyer he had argued the famous Calder case, which led to the recognition of Indigenous rights and title to traditional territories.

Berger’s mandate was to examine the social, economic and cultural impact of the vast project. He wasted no time, setting up preliminary hearings in April and May 1974.

This was a smart move: it allowed him to feel out the players, particularly the interested parties other than the pipeline companies. It also allowed him, with input from the parties, to define and even expand his terms of reference. So, the mandate (expanded) was clear and the interested parties brought into the fold.

Then Berger did a quick tour of the Western Arctic. I recall him travelling by Jet Ranger helicopter from Inuvik across the north shore of the Yukon, looking down on wolves, bears and migrating caribou, and going over the British Mountains to the village of Old Crow, still without roads to the outside world today.

When Berger landed on the Old Crow airstrip, an RCMP van came to pick him up for the short trip into town. Berger, a son of an RCMP officer, declined politely and walked into town with Chief John Joe Kaye, who invited him to his house for a caribou diner. In spite of a stomach problem, the judge immediately accepted.

The chief asked whether Berger’s inquiry would come to Old Crow and, if so, how long it would stay. Berger replied that yes, the inquiry would come to Old Crow, as it would to all the villages affected by the proposed pipeline. He would listen to all the people and stay as long as it took. Other government officials had a pattern of flying in and out the same day.

Then Berger, to the consternation of Ottawa, announced the inquiry would be delayed a year. In that year he sent University of British Columbia professor Michael Jackson, with his family, to visit the Indigenous communities and explain the inquiry to the people.

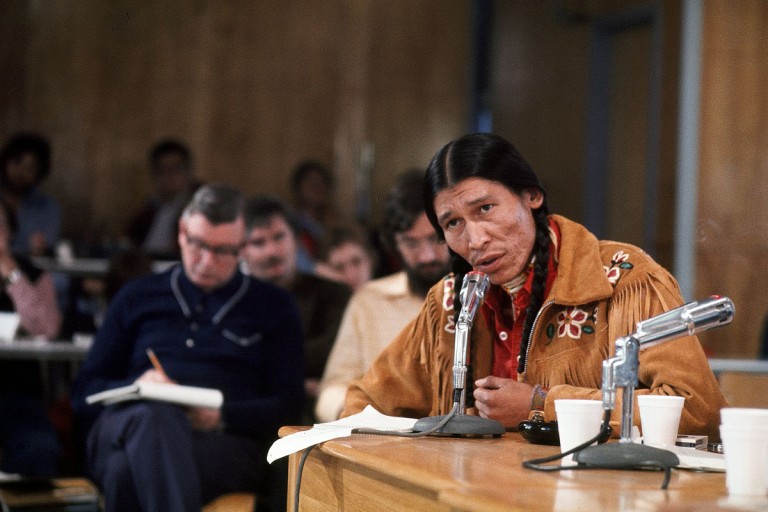

Berger Inquiry. Photo: Michael Jackson / Prince of Whales Northern Heritage Centre

This later resulted in enormously successful community hearings where people were prepared and spoke in an informal setting, in their own languages, to Berger.

The CBC reported these hearings in six languages. The north was connected. When Globe and Mail columnist Martin O’Malley joined the hearings and wrote about them, southern Canada was enthralled. Canadians think of ourselves as northern peoples but this was the first time most of us had seen the real north.

Berger did come back to consult Old Crow. I was lucky enough to witness the hearing there. Here is what I wrote at the time.

“I am Judge Berger. I am here to listen,” he said at the beginning of the hearing. And listen he does, with dogged patience. He looks at each witness and doesn’t interrupt. He is in his shirtsleeves now, his corduroy jacket on the back of the chair. An unused ashtray is there to gavel the meeting to start. “I find that I am learning a great deal from all that you have told me.” When the attention begins to wane he will take a break, but until then he is alert for each witness. There is respect, on both sides.

After almost a week in town Judge Berger thanks the interpreters and the people for the friendship they extended to him, his staff and to the members of the CBC and press and the participants in the Inquiry. “These people from the CBC and the Press come along with me to enable you to tell the people of the north and the people of Canada what you think.” He explains that he’s going on tomorrow to visit the whalers from Aklavik out on the Mackenzie Delta and then he’s going back to Yellowknife and later to Fort Liard in the southern Mackenzie to hold another community hearing. “I have to hear what all the people in the Mackenzie Valley and the Mackenzie Delta and the northern Yukon think of the pipeline, then I have to send a report and recommendations into the government, and when I am considering what I will recommend to the government, I will be thinking about what all of you have said to me over these three days about the land and about your way of life.” His comments are interpreted and then there is applause. He heard from 81 people in this village of 250. And he would visit another 30 settlements to hear people in five other languages. On adjournment the Inquiry Staff and the Judge would play baseball with the locals under the midnight sun.

As well as community hearings, formal hearings were held under commission counsel Ian Scott and Stephen Goudge and a series of funded interveners cross-examined Arctic Gas experts on such topics as building in discontinuous permafrost.

Berger asked UBC law professor Andy Thompson to round up the environmentalists into one group and, for the first time, secured intervener funding for them (thanks to a young, Jean Chrétien, who was the minister responsible for Indian and Northern Affairs).

Berger fashioned a standard for intervener funding — a clear interest that ought to be represented at the inquiry, a distinct interest, a record of concern, inadequate resources to represent that interest and a plan as to how the intervener would use and account for the funds. He also ordered all the parties to release their reports, including Arctic Gas, to create a level playing field.

Southern Canadians were also consulted by means of open hearings in our largest cities. The inquiry even made a short film showing a bit of the northern community hearings and then identifying Arctic Gas and other official interveners. I was shown just before the southern hearing witnesses testified before Berger, this time in a suit. When people from Halifax complained that inquiry staff had not scheduled a hearing there on the grounds the pipeline was in the west Berger overruled the staff. “The Maritimers are Canadians too,” he said. “They too should be heard.” And they were.

The hearings had another happy result. A generation of young native leaders got to appear before the judge, as their parents were less comfortable in English. What a generation it turned out to be.

Nellie Cournoyea worked with the Committee for Original People’s Entitlement, which was the Inuit group. Later she became a member of the Legislative Assembly of the Northwest Territories and premier.

Dave Porter, who used to carry the equipment for the CBC crew, became a great aboriginal leader in the Yukon.

Jim Antoine, then the quiet but charismatic 26-year-old chief of the Fort Simpson Dene, also later became premier of the N.W.T. George Erasmus cut his teeth before the inquiry appearing for the Indian Brotherhood of the N.W.T. (later named Dene Nation). He later became national chief of the Assembly of First Nations and co-chair of the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples.

A boyish Stephen Kakfwi helped organize the Dene’s presentations to Berger. Later he became president of the Dene Nation and premier of the Northwest Territories and a supporter of a future pipeline.

All told Berger held hearings in log cabins, village halls, besides rivers, and in hunting and fishing camps throughout the Western Arctic. There are 8,438 pages of transcripts in 77 volumes and 662 exhibits from these “community hearings.”

When the southern hearings concluded on Nov. 19, 1976, there were 900 pages of submissions and over 40,000 pages of transcript and more than 1,500 exhibits. The inquiry cost $5.3 million which was a remarkably modest number given the magnitude of the job.

On April 15, 1977, Berger released Volume I of his report, a mere 200 pages, beautifully written and filled with pictures of our stunning north. Volume 2 followed with more technical recommendations to be implemented if and when gas was to flow done the Mackenzie Valley. The work turned out to be among most popular commission reports ever.

Overall, Berger recommended a pipeline down the Mackenzie Valley corridor, but called for a delay of 10 years in construction to give time for the settlement of native land claims along the route. Most of them are now settled.

However Berger recommended that no energy corridor should be created in the Northern Yukon. Instead, the report said, a national park should be created in the Northern Yukon to protect the calving grounds of the Porcupine Caribou herd. A wilderness park called Ivvavik was established in the northern Yukon in 1984, and one called Vuntut in 1995. They are both part of the Inuvialuit (Inuit) and Vuntut Gwich’in (First Nations) land claims settlement. That means, says Berger, both parks are constitutionally entrenched: their character and boundaries cannot be altered except by constitutional amendment. Canada has done its part to save forever the migrating caribou. (The Americans have not

.)

And the results today?

Land claims have been settled and a possible new pipeline has been proposed, then shelved

. This time, the consortium of resource companies (Imperial Oil, Shell, Exxon) had a new partner, with a one-third interest — the Aboriginal Pipeline Group, which represented the Indigenous peoples of the N.W.T. Its website said: “We are committed to respecting the people of the North and the land and environment that sustains them.”

The market is not yet ripe for Arctic gas but if that happens, Indigenous people, properly consulted and heard, will be partners, not bystanders.

Can lessons taught by Berger many years ago be applied today to the Kinder Morgan issue? Coastal First Nations and environmentalists, if really consulted, have a lot to tell us about protecting the waters and the animals. No doubt they will mention the poor response to the 2015 oil spill

from the MV Marathassa into English Bay.

Can there be a better spill cleanup system? Can there be perhaps fewer tankers than originally proposed? Can there be a new site for the terminal; say Cherry Point in Washington or another nearer to the open ocean? Can there be another way to consult and meet the concerns of First Nations?

A former Supreme Court of Canada justice, Frank Iacobucci, has been given the task of doing proper consultations. He’s a person not unlike Berger.

Berger taught us something critical about consultation. You have to listen, be patient and show respect.

Then you actually implement what you hear.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

Artist Alison McCreesh’s latest book documents her travels around the Arctic during her 20s. In...

I’ve watched The Narwhal doggedly report on all the issues that feel even more acutely...

Establishing the Robinson Treaties, covering land around Lake Huron and Lake Superior, created a mess...