Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

Yesterday I realized what it might feel like to live in an acidifying ocean. After waking up to red hazy light filtering through my blinds, I prepared to take my daily coffee walk — one of my COVID-19 rituals to break up the monotony of working from home in my small bedroom. Upon stepping outside, my first inhalation brought acrid smoke and ash from 4.7 million acres of land burning in another country into my lungs.

The air we breathe in Vancouver right now is unhealthy. It is filled with toxins that compromise our respiratory systems. It brings sadness and fatigue into our minds and bodies, and most importantly, it does not affect us equally. Portions of our population — the elderly, the young and the immunocompromised — are at a significantly higher risk of acute health impacts caused by the smoke, which further increases their vulnerability to COVID-19.

This experience is exactly what is happening to our ocean and the millions of sea creatures who are trying to breathe, grow and survive in increasingly corrosive and acidic seawater.

Ocean acidification is caused by the growing concentration of carbon dioxide in our atmosphere, which increases the amount of carbon dioxide that dissolves into the sea. Once it enters the ocean, carbon dioxide interacts with water molecules and undergoes two chemical reactions, the outcome of which is increased seawater acidity and altered carbonate chemistry.

Since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution (circa 1760), the ocean has increased in acidity by approximately 30 per cent — a direct result of humans burning fossil fuels. Because our carbon emissions have accelerated immensely over the past two generations and are projected to continue accelerating under business-as-usual scenarios, by 2100 we can expect a 150 per cent increase in seawater acidity. In essence, over the next 80 years we can expect our ocean’s acidity to increase five times faster than it did over the past 260 years.

In certain places in the world, these changes in seawater chemistry are more significant due to localized water circulation patterns. For example, upwelling during spring and summer months along the Pacific Northwest coast brings naturally acidic waters from deep in the ocean to the surface. This means that when we consider the ever-increasing baseline acidity caused by ocean acidification, seawater around Vancouver and down the burning coastal states of Washington, Oregon and California is becoming more corrosive to certain life forms, specifically animals that build shells out of calcium carbonate.

In British Columbia, we have come to expect to breathe smoke-filled air for several weeks each summer.

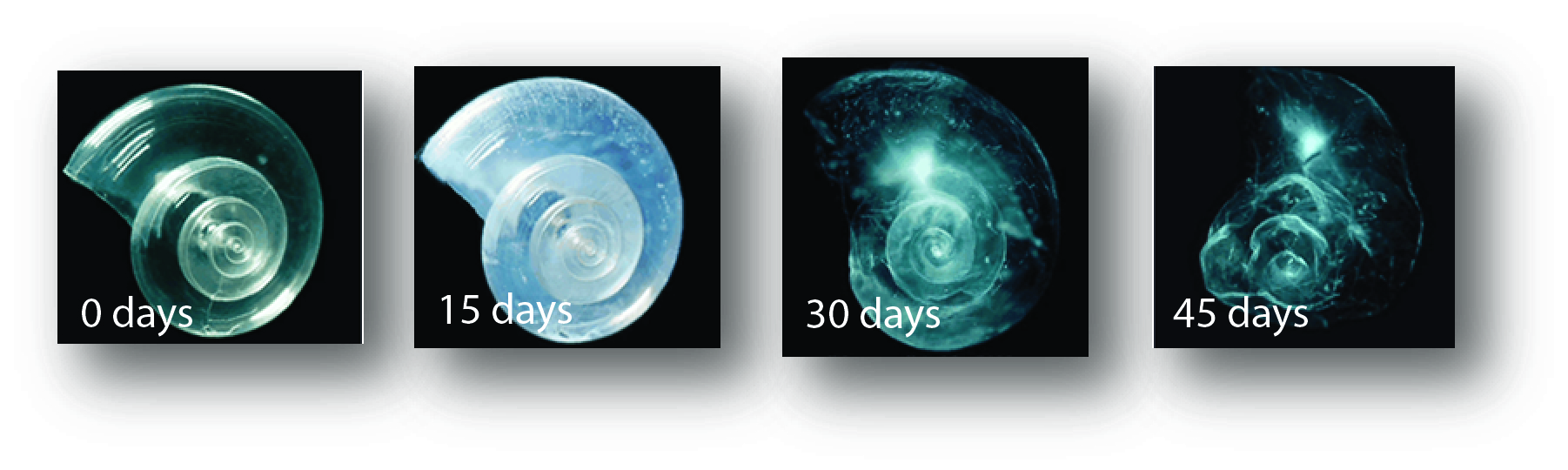

Like us, many animals along our coast are guaranteed to experience seawater for several weeks each year that is so acidic and corrosive that it severely compromises their ability to build, grow and repair their shells. These effects are particularly impactful to small animals, including juvenile and larval invertebrates and plankton, such as pteropods, whose shells are so thin that even the smallest impairment to shell growth and development can cause death.

Sea butterflies rely on calcium carbonate minerals to form their shells. The availability of these minerals lessens as water becomes more acidic. Photo: Jens Terhaar

Degradation of a sea butterfly shell over a 45 day period when exposed to increased acidity. Photo: Pacific Marine Carbon Laboratory / NOAA

Already, shellfish aquaculture facilities along the Pacific Northwest coast from Oregon to British Columbia are suffering from the mass mortality of larval oysters, mussels, clams and scallops. This effect of ocean acidification on economic opportunities and livelihoods is not just a Pacific Northwest phenomenon: it is estimated that globally, ocean acidification will cause annual losses of more than US$1 trillion to the world economy by 2100

. Importantly, this stark number does not include the far larger impact that ocean acidification will have on our coastal cultures, health and well-being.

By the end of my coffee walk, I realized how the reduction in air quality that we are currently experiencing is analogous to the alterations in seawater chemistry that are happening all over the world. I began to understand how the changes in quality of life and even survival that my local and global community will continue to experience over the coming decades is much the same as that of oysters, plankton and corals in the sea.

The extent to which sea creatures and humans can adapt to the rapid rates of ocean acidification and climate change is uncertain and our challenges are magnified when we consider the many additional pressures that we all face, such as disease and pollution.

While this seems overwhelming, our reality in 2020 is one that we cannot ignore. We must proceed forward with a strong acknowledgement and acceptance of the multiple pressures that our society and globe is experiencing. We know the actions that we need to take to address climate change’s threat to our health, livelihoods and ocean: reduce and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions; adapt our economic development patterns; and reconnect our cultures and societies with the nature that supports and surrounds us.

As governments and communities around the world design COVID-19 recovery plans, we have an incredible opportunity to elevate the role and impact of each of these three actions so that we can protect our lives and values in the face of growing changes. The duration and effects of smoke and acidity for years to come depends on what we do now and how we choose to respond and adapt.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion