Bill 5: a guide to Ontario’s spring 2025 development and mining legislation

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

With B.C.’s commercial herring fishery set to open in the Strait of Georgia on Sunday, Nov. 24, W̱SÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs are urgently trying to get a meeting with the federal government to get a moratorium in place.

Tsawout Hereditary Chief Eric Pelkey, or WIĆKINEM, said herring are in decline and the chiefs want to protect the remaining herring in the Salish Sea between the southern coast of Vancouver Island and the mainland. They want to see a moratorium on the commercial herring fishery like those put in place in Haida Gwaii and the west coast of Vancouver Island.

“It really needs to be shut down in our territory to allow them to re-establish and thrive again,” WIĆKINEM said.

“Without the herring there can be no salmon, no seals, no killer whales as a result of no salmon. All these things all depend on herring to thrive.”

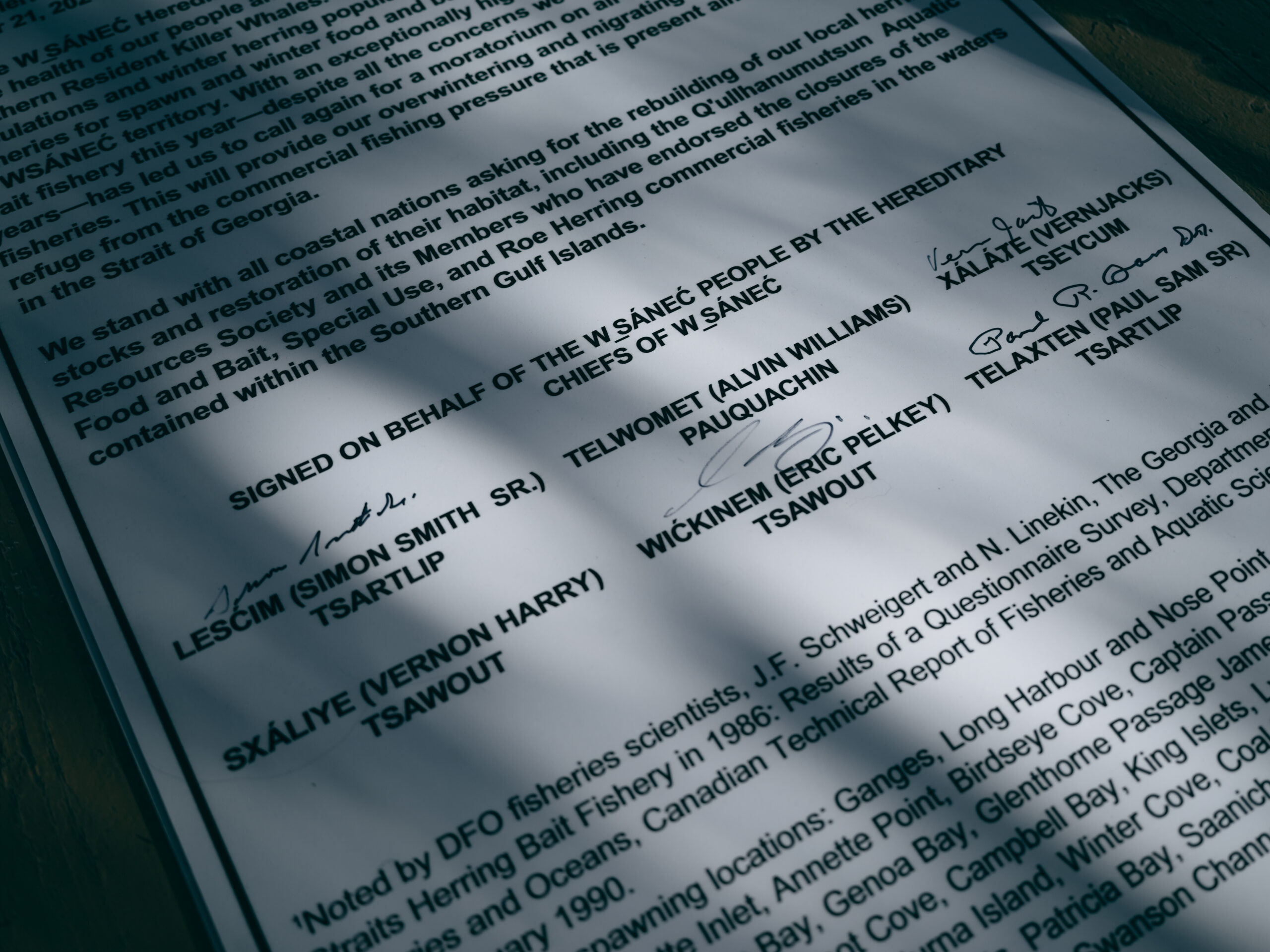

Last week, the hereditary chiefs signed a declaration calling for a 20-year closure in the Strait of Georgia to allow herring to recover. They are asserting their Treaty Rights to fish as they did before contact, as protected in the Douglas Treaty. They are maintaining W̱SÁNEĆ Title and do not plan to back down, he says.

“[Fisheries and Oceans Canada] has been pretty quiet,” WIĆKINEM says. “Nobody has returned my calls.”

He says even though their concerns have been ignored for years, the chiefs are sending letters to Minister of Fisheries, Oceans and the Canadian Coast Guard Diane Lebouthillier seeking a meeting.

The chiefs have high hopes an immediate moratorium would benefit the small, silvery fish. Earlier this year, Ahsousaht First Nation reported a strong surge of herring after the federal government closed the commercial fishery for the fourth consecutive year on the west coast of Vancouver Island to protect the population.

“This may be the last opportunity to stop the collapse of this species,” Tsartlip Hereditary Chief Paul Sam Sr., or TELAXTEN, said in a statement.

“We need to give the herring time to recover so that it can be fished sustainably again, as my great-grandfather did.”

After the chiefs’ declaration last week, Vancouver Island news outlet CHEK Media reported the BC Seafood Alliance and other commercial fishing spokespeople saying herring numbers only look low, because the fish move around and spawn in different places. But, they argued, the populations are holding steady.

The BC Seafood Alliance and the Herring Industry Advisory Board were not able to comment before publication.

WIĆKINEM disputed the alliance’s claim that herring migrate around the territories. “The notion that the herring just migrate all around the territories is really misguided. … [Herring] come back to the same place. They come back in groups, and they’re like families.”

And he says despite constant insistence that herring are better than ever, “we don’t see herring at all in our territory.”

“The last gasp in our territory seems to be out in the Georgia Strait,” he says. “All around the Gulf Islands and all around the Capital regional area, there used to be really healthy spawns of herring.”

He said they do see juveniles, or fingerlings, trying to establish in the area. “The problem is, as soon as those fingerlings grow up to be really healthy adult herring, they open it up commercially again and clean them right out again,” he says.

In its 2023/2024 Pacific herring integrated fisheries management plan, Fisheries and Oceans Canada (commonly known as DFO) acknowledges First Nations concerns about herring stocks and said “continued efforts to consult and collaborate with First Nations (and others) … remain a priority.”

The department outlines management measures already taken to address concerns, such as closing some areas in the Strait of Georgia since 2018 to roe herring commercial fisheries and advising commercial fleets to avoid locations where First Nations have said they are harvesting.

Coastal First Nations have lived with and relied on seafood for millennia. It’s a central pillar of their food security.

“Pacific herring are part of the circle of life, vital to the health of our people. Our cultural survival and the survival of our relatives, such as the Chinook and southern resident killer whales, depend on the herring,” SXÁLIYE, Tsawout Hereditary Chief Vernon Harry, said in a statement.

WIĆKINEM says that his sister passed away from liver disease despite never drinking alcohol in her life. Around the time of her death, WIĆKINEM says he learned oily fish like herring can help mitigate liver disease — reinforcing his drive to strengthen his community’s access to its ancestral diet.

“How the health of our people is affected by the lack of our traditional diets, which is seafood, it hurts me,” he says.

Before contact, First Nations had access to herring year round, he says. Herring provided a big feast in the spring, while smoked and dried fish lasted through the winter and served as a trade item.

Even in his own youth, WIĆKINEM recalls, fish were plentiful in the area. Right into the 1970s, herring was still a reliable food source. Then, the decline began. “Every year the spawning got worse until there was nothing,” he says.

“We were screaming for a closure.”

Decades later, the hereditary chiefs are fighting the same battle. It’s a fight WIĆKINEM says he will continue, and will pass onto his nephew when he steps into the hereditary role.

“We really have to establish ourselves, as W̱SÁNEĆ hereditary chiefs, as a viable alternative and work in a way that doesn’t threaten the autonomy of First Nations governance. Because we will always be here.”

Updated March 5, 2025 at 11:00 a.m. PT: This story has been updated to correct a caption that misidentified XÁLÁȾE, Tseycum Hereditary Chief Vern Jacks.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy