In Tlingit territory, the fight to protect herring is complicated

An excerpt from “We Survived The Night” by Julian Brave NoiseCat

Canada is ordering the Yukon government to re-evaluate a proposed open-pit and underground mine after finding the territory failed to exercise due diligence when assessing the project and its impact on First Nations’ Rights.

In October, the executive committee of the Yukon Environmental and Socio-economic Assessment Board recommended the Kudz Ze Kayah mine, proposed for the Pelly Mountain range within the territory of the Liard First Nation and the Ross River Dena Council, proceed without a formal socio-economic and environmental assessment.

A Jan. 22 letter from Fisheries and Oceans Canada and Natural Resources Canada states the committee made that recommendation without sufficient explanation as to how First Nations’ Rights were considered and how mitigation measures would address the negative impacts of the project.

The two federal departments are requesting the committee evaluate their assessment of the project, especially its significant adverse effects and impact on First Nations rights, via a formal referral for reconsideration.

“The written referral outlines additional information being sought and will provide an opportunity to further address First Nations’ perspectives and how potential impacts to Indigenous rights can be mitigated,” Austin Beaton, a spokesperson with Natural Resources Canada, told The Narwhal in an email.

“Canada has learned from experience that timely, meaningful consultation with Indigenous groups is an essential component of the decision-making process.”

Yukon Premier Sandy Silver told The Narwhal he is disturbed by the federal government’s move, which he called “unprecedented.”

“This recent decision undercuts our authority and it sends a troubling signal over who holds the pen on major projects like this,” he told The Narwhal.

In a 2003 devolution process, Ottawa delegated power to the Yukon government so the territory could, among other things, make its own resource management decisions.

“Devolution happened for a reason,” the premier said. “Local decisions should be made by local governments.”

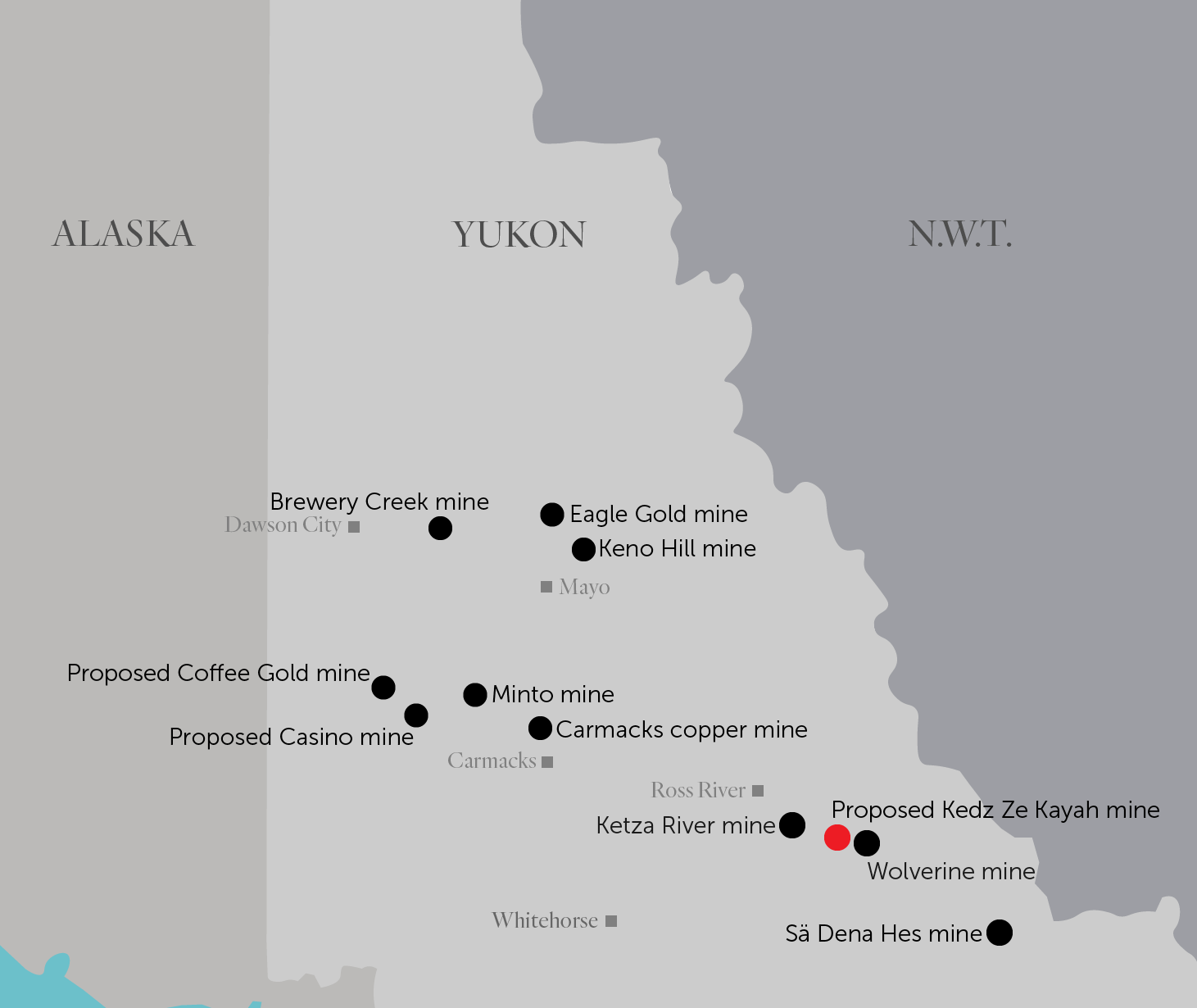

Location of the Kudz Ze Kayah in southeastern Yukon. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

BMC Minerals, the Vancouver-based company behind the project, hopes to extract 1.8 million tonnes of zinc, 600,000 tonnes of copper and 350,000 tonnes of lead from the Kudz Ze Kayah mine over a 10-year lifespan, after which a 26-year closure and reclamation process will take place.

The federal government’s order comes on the heels of a letter from Stephen Charlie, Chief of Liard First Nation, which states the assessment board “erred in law” when recommending the project move ahead for government approval without a full review under the territory’s assessment act.

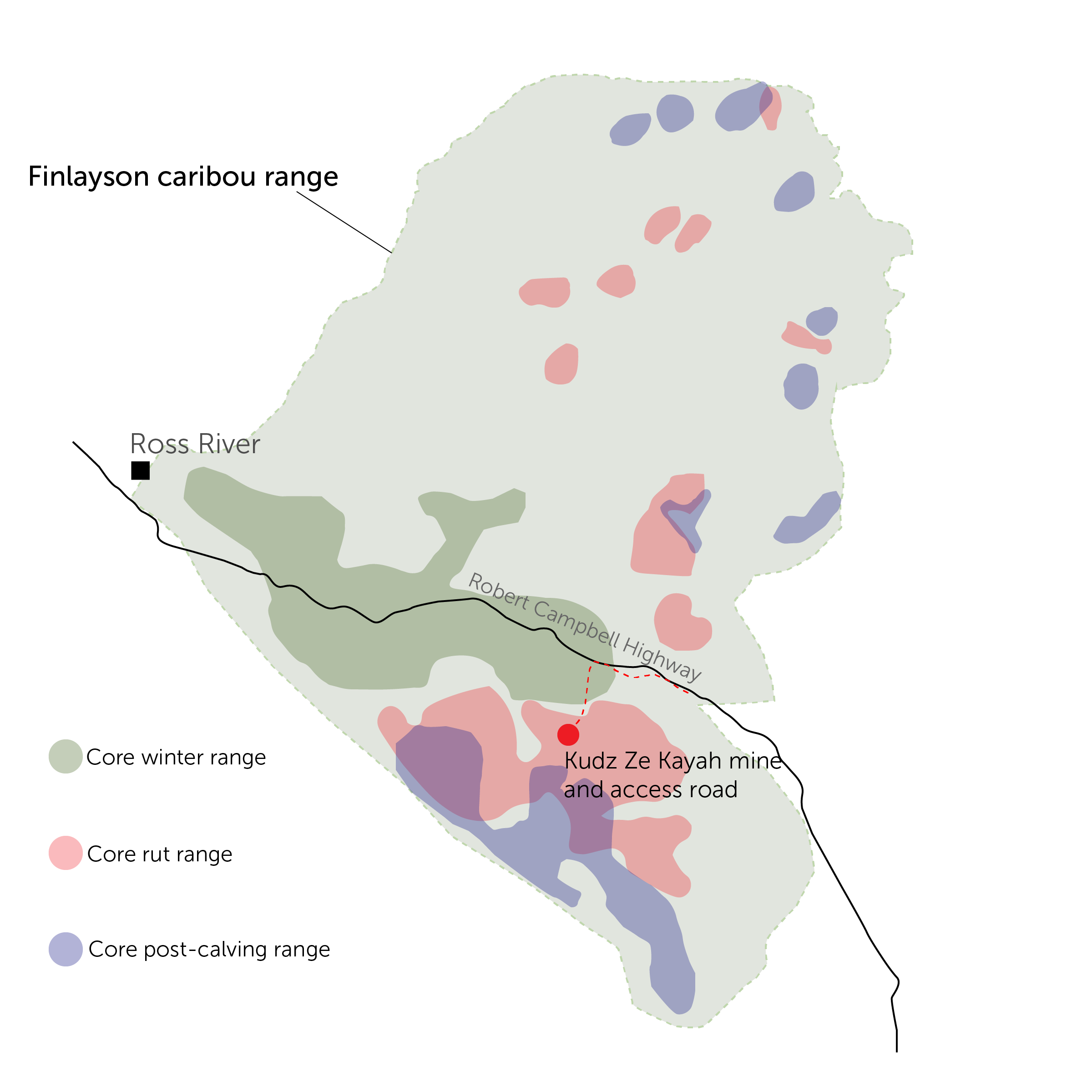

In its screening report for the project the executive committee acknowledged the mine would have “significant adverse effects” on water, traditional land use and wildlife and will contribute to the “likely decline” of the Finlayson caribou herd, a subsistence food resource for the Kaska Nation, comprised of five Dene-speaking First Nations spanning the Yukon and British Columbia border.

The Kaska nation’s traditional territory encompasses 24 million hectares — equivalent to the size of the state of Oregon — stretching across B.C., Yukon and the Northwest Territories.

The project is located in the middle of the Finlayson herd’s winter habitat, where caribou calve and rut, and is also situated near the herd’s migration corridors.

The Kudz Ze Kayah mine is located within the Finlayson caribou herd range. Source: BMC Minerals. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

The report noted caribou “habitat loss due to the mine’s footprint, including its open pit, waste storage facilities and [water management ponds], will be permanent and irreversible,” the report states. “Beyond direct reductions in habitat loss, the effectiveness of most mitigation measures at reducing habitat disturbance during operations is largely unknown.”

Charlie’s letter, addressed to Silver and Minister of Northern Affairs Dan Vandal argues that because the project would infringe on Kaska harvesting rights the mine should be outright rejected or subject to a panel review, the most stringent form of environmental assessment in Yukon.

“The project, as currently proposed, should be rejected until it can be confidently demonstrated, based in scientific evidence and grounded in Kaska knowledge and ways of knowing, that Kaska Rights and Title will not be extinguished by this project,” Charlie wrote.

Allan Nixon, BMC’s vice-president of external affairs, told The Narwhal in an email the executive committee’s review “was professional, thorough and comprehensive,” adding that all parties had enough time to provide input “to guide the conclusions reached.”

The executive committee noted BMC had not completed a full assessment of caribou habitat loss associated with the project and suggested impacts could be much greater than the proponent anticipated.

“Effects to calving habitat and movement corridors are very likely, but models were not available to quantify effects,” the committee’s report states. “This is a significant knowledge gap.”

Despite the seemingly profound impacts on the caribou, the board argued these negative effects could be “eliminated, controlled or reduced” through mitigation measures carried out under a specific Kudz Ze Kayah management plan.

According to the committee, measures under that plan would include ongoing geotechnical studies, sustained water quality monitoring efforts and limiting speeds on mining access roads. The committee also recommended the Yukon government and affected First Nations develop a joint management plan for the Finlayson caribou herd informed by science and traditional knowledge.

“We thought that the management plan would mitigate any of the adverse effects to caribou,” Laura Cabott, executive committee member and chair of the assessment board, told The Narwhal. “It’s pretty extensive.”

Charlie strongly disagreed, however, stating in his letter that the mitigation measures proposed are “unproven,” especially where caribou are concerned.

“There is no evidence they will effectively mitigate these adverse effects or prevent the continued decline and potential extirpation of the Finlayson caribou herd.”

“Predicted impacts on the Finlayson caribou herd threaten the continued viability of Kaska harvesting rights, which depend on a healthy and sustainable herd that has a harvestable surplus,” Charlie wrote.

Charlie did not respond to requests for comment.

According to premier Sandy Silver, the Yukon government has already conducted a “comprehensive review” of the Kudz Ze Kayah mine although he acknowledged more work can be done to consult with First Nations on the project. Photo: U.S. Department of Agriculture / Flickr

In a Jan. 25 statement, Silver said the Yukon government was poised to accept the assessment board’s recommendation and issue an approval of the mine.

Asked why the territorial government was ready to approve the project, Silver told The Narwhal the assessment process conducted by the Yukon environmental assessment board’s executive committee “resulted in a very comprehensive review.”

He also said the management plan developed between the committee and the company was sufficient.

“The system works,” he said. “The recommendations, you know, they’re onerous — they hit the boxes.”

The premier noted, however, that more engagement with First Nations is warranted.

“As a government, we definitely respect that much more consultation still has to happen,” he said.

Charlie’s call for a full panel review of the Kudz Ze Kayah mine raises questions about how such a process would play out because no review of that kind has ever been completed on a mine in Yukon.

One panel review has been initiated but not completed for Casino Mining Corporation’s massive Casino Mine west of Carmacks, which would produce 8.9 million ounces of gold over roughly 22 years. The company is in the process of preparing its submission for that review.

Panel reviews are initiated when a project is expected to carry serious environmental impacts or stoke significant concern among the public. Equipped with their own budgets, the reviews are quasi-judicial processes and require public hearings take place.

Cabott told The Narwhal the assessment board, the federal government and the Yukon government all have the authority to subject the Kudz Ze Kayah mine to a panel review.

Cabott said there has been no formal request to initiate a panel review into the Kudz Ze Kayah project.

“Is that option still available in this stage of the assessment process? Yes. However, it’s not a focus of ours right now,” she said.

The Finlayson caribou herd would likely suffer population declines were the Kudz Ze Kayah mine to go ahead. Photo: Yukon Government

Last year, Yukon First Nations leaders called on the assessment board to extend the public comment period for the project, citing potential effects to the Finlayson caribou herd and the possibility of increased rates of sexualized violence toward First Nations women if outstanding issues associated with the project aren’t addressed.

A panel review could provide an opportunity for these concerns to be addressed with more First Nations and public engagement.

Lewis Rifkind, mining analyst with the Yukon Conservation Society, told The Narwhal a panel review would be a “big deal, especially for the Yukon.”

“If we started setting a precedent for mines that are of environmental or First Nation concern — which I would argue is anywhere in the Yukon — it might be a default to go to a panel review,” he said.

A panel review might also consider how the Kudz Ze Kayah mine might fit into Yukon’s larger relationship with mining projects and their cumulative and long-term impacts on the environment and First Nations.

Abandoned mines are commonly found in southeastern Yukon. There’s the beleaguered Wolverine mine, for instance, which has yet to be fully cleaned up and has cost millions of dollars just to keep it from leaching contaminated water into the surrounding area.

Rifkind added that Kudz Ze Kayah could contribute to a proliferation of new exploration and mining in the area.

“Nothing attracts success like success,” he said. “Once you’ve got a successful mine, other companies are going to start looking for neighbouring ore bodies and you get sort of a sprawl happening of mining explorations and, possibly, actual mines.”

The prospect of additional exploration and mining projects piggybacking off the infrastructure built for Kudz Ze Kayah could mean more stress on the Finlayson caribou herd.

“The impact on the caribou in that situation would be terrible because you start to get cumulative impacts happening,” Rifkind said.

Road construction has been firmly cautioned against elsewhere in the territory. Late last year, the Yukon government cancelled the 65-kilometre ATAC resource road due to mounting concerns the road would invite further industrial incursion into the Beaver River watershed.

The assessment board launched another public comment period for the Kudz Ze Kayah project on Feb. 1. When the comment period closes on March 8, the board will begin to make changes to the screening report based on feedback from Yukoners and the federal government’s decision, Cabott said.

“We will work to address areas of concern,” she said.

In his letter to the premier, Charlie said he wonders why the panel review option is available if Yukon is not going to make use of it.

“It is difficult for Liard First Nation to understand why the panel option exists in the legislation if not to address major projects [that are] subject to Kaska Title in circumstances that make serious infringement — and potential extinguishment — of Kaska harvesting rights inevitable.”

Read more: Curing the ‘colonial hangover’: how Yukon First Nations became trailblazers of Indigenous governance

Six hundred samples. Roughly 180 sites across the Canadian Arctic. And more than 3,000 microbes providing more than four trillion pieces of data on the...

Continue reading

An excerpt from “We Survived The Night” by Julian Brave NoiseCat

Data shows an oil company owed 10 times the government’s limit on unpaid taxes when...

Neighbours cried foul when a developer built a trail through a marsh near Orillia, but...