The Narwhal picks up four Canadian Association of Journalists award nominations

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

At least one person has been fined as droves of people from outside Yukon enter the territory to illegally pick morel mushrooms on a First Nation’s land.

Selling the foraged mushrooms can net thousands from corporation-backed buyers, spurring a rush of activity to get a piece of Yukon’s suddenly open commercial harvest.

“It’s a little bit of a gold rush of mushroom pickers,” said Josee Tremblay, manager of lands and resources at the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun, located in central Yukon. “There are people all over the territory.”

The Yukon government cancelled the commercial mushroom harvest on April 17 in light of the COVID-19 pandemic. On May 26, officials reversed this decision, doling out permits to Yukon residents. Harvesters from outside Yukon are permitted to pick for personal use only — but that doesn’t appear to be what’s happening.

Yukon has been in lockdown since March due to the novel coronavirus pandemic, with out-of-town visitors allowed in under special circumstances and requiring two weeks of quarantine. Visitors travelling through Yukon en route to Alaska have a 24-hour window to get through the territory — something Tremblay said is being abused, with some people overstaying the allotted time.

On July 1, Yukon and British Columbia became part of the same “bubble,” meaning travellers could cross between the jurisdictions without self-isolating for 14 days. But the foragers around Na-cho Nyäk Dun settlement lands had licence plates from Alberta, New York, Texas — even Germany.

“We’re receiving phone calls all around the clock about plate numbers from all sorts of places,” Tremblay said.

And, she said, pickers were showing up in the territory a month and a half before the southern border reopened.

The area near the McQuesten airstrip near Stewart Crossing, Yukon, packed with morel pickers’ vehicles — many from outside the territory. Photo: Shelby Leslie

Several wildfires in Na-cho Nyäk Dun’s territory last year created fertile ground for morel mushrooms, a species that are commercially harvested in the territory and sold to restaurants and customers around the world. Now these burns are acting as a magnet for foragers from outside the territory, during a time when most Yukoners — particularly those in small communities — are still on high-alert for the threat of COVID-19.

Beginning the weekend of June 27, Tremblay said 50 cars were spotted by Na-cho Nyäk Dun lands officers around the McQuesten airstrip — near the tiny settlement of Stewart Crossing.

“It turned into a mushroom picking camp overnight,” Tremblay said, adding that gunshots were heard by Elders at a nearby fish camp.

During that weekend and the following week, Tremblay said lands officers had to put out several abandoned campfires and found garbage left behind around the airstrip and near Ethel Lake.

Mushroom pickers have taken to other parts of their territory as well, she said, including near Keno City and Elsa, which were evacuated last summer due to wildfires.

The issue here is two-fold: pickers are harvesting without the necessary permission, and many of them shouldn’t be in Yukon at all.

Many of the people entering the territory could be financially supported by corporations, said Shelby Leslie, the chief executive officer of Forest Foods, a B.C.-based company the First Nation contracted to help manage non-timber resources such as mushrooms, medicinal plants and berries.

“The corporations that are coming up here and doing this illegally — that’s an issue,” he said.

Companies give field buyers cash — upward of $45,000 — and the buyers fan out across the country to morel hotspots such as Yukon, Northwest Territories and B.C., wherever there have been burns, Leslie said. They set up buying stations, where they acquire the freshly picked mushrooms from harvesters. The buyers then dry the morels, if the picker hasn’t already and they’re eventually shipped across North America and overseas.

A wildfire ravaged the land around Keno City, Yukon, in 2019, making for a bumper crop of morel mushrooms this year. Photo: Shelby Leslie

But these aren’t necessarily the plans buyers lay out to officials at the Yukon border. “They’ll say they’re going to Atlin, B.C., and then they go to the McQuesten airstrip, they park their stuff and they start buying,” he said. And the buyers often call up pickers from down south, he said, rather than paying local harvesters for the work.

“They’re all completely funded by these large companies. The buyers and the companies like that, there’s no regulation. We’re talking about millions and millions of dollars of resources, every year.”

A permit is required to harvest mushrooms for commercial sale on Crown land in Yukon but, Leslie said, permits are free, making the entire regime an easy one for companies to exploit.

“There is nothing in Yukon legislation that addresses mushroom buying, only commercial harvesting,” he said.

Pickers are required to get permission from Yukon First Nations to forage on their settlement lands — areas wholly owned by the nations — but many are skipping this step, Tremblay said.

She added that one person from B.C. has been charged after taking part in the mushroom harvest on Na-cho Nyäk Dun’s land.

The individual entered Yukon on June 16, while the territorial borders were largely closed to outsiders, and did so under the false pretence of working for a miner in the Dawson City area, where they intended to self-isolate, said Nigel Allan, information officer with the Yukon government’s Health Emergency Operations Centre. The individual was, in fact, a mushroom buyer, though that’s not what netted them the charges.

Picked morel mushrooms. Photo: Shelby Leslie

Morel mushroom. Photo: Shelby Leslie

Since buyers aren’t regulated under Yukon’s Forest Resources Act, outside buyers who are eligible to enter the territory can buy mushrooms, confirmed Jesse Devost, spokesperson with the Department of Energy, Mines and Resources, in an email.

But this buyer, like many outsiders taking part in the territory’s morel harvest, appeared to be lying on entry.

The individual faced a slew of different charges for a total of $1,063. They were charged $575 Under the Civil Emergencies Measures Act for the false declaration, $172 for an unauthorized harvest and $230 for providing false information to a forest resource officer, Allan said.

“The RCMP also charged him under the Highway Traffic Act for the unauthorized use of a motor vehicle plate,” he said, noting the $86 fine.

The person hasn’t been removed from the territory as there is no legal authority to do so, Allan said.

The plan to reboot the commercial harvest at all this year came as a surprise to the First Nation of Na-cho Nyäk Dun, Tremblay said

“Why we’re dealing with this mushroom picking issue is because this was basically done without consultation with the First Nations,” she said, adding this meant the broader community didn’t have an opportunity to weigh in on the issue.

“[The Yukon government] reopened mushroom picking and they didn’t give us time to consult or do anything.”

The First Nation wants to see better consultation and adequate timelines in the future, Tremblay said. It wants to be treated like a government, she said, adding that anything else would contravene the nation’s self-governing agreement with the territory and federal government.

Allan said Yukon government officials have been in contact with the First Nation since February regarding the mushroom foraging issue but added the COVID-19 pandemic complicated efforts.

“During the mushroom harvesting season, we have been in regular contact with the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun, responding to concerns and implementing mitigation measures wherever possible,” he said in an email. “Several inspections with the First Nation of Na-Cho Nyäk Dun Lands Officers and Natural Resource Officers have been undertaken, including inspection by road and water to remote camps.

He said the nation has been updated regularly on these inspections and the territory’s natural resource officers will continue to monitor harvesting activity until the end of the season, in mid- to late-summer.

“At the forefront of our discussions has been the need to keep the community safe from COVID-19 transmission,” Allan said.

Na-Cho Nyäk Dun First Nation is attempting to take greater control over activities on its lands. Tremblay said the partnership with Forest Foods has yielded a host of different foraging workshops, with members of the nation given priority, though they’re open to all harvesters. And the company is helping the First Nation close gaps in its legislation around permitting activities on its land.

Right now, the nation’s lands officers can only report issues within Na-Cho Nyäk Dun’s territory to the Yukon government — they’re the “eyes and ears” of the First Nation, Tremblay said. But the First Nation is currently reviewing its Lands and Resources Act, which could result in more power given to officers to enforce laws and even lay charges. This change could come at the end of August, when the nation has its general assembly.

Tremblay said the nation doesn’t want to see any mushroom buyers — aside from Forest Foods, which has a licence from the First Nation — on its settlement land and traditional territory.

“The First Nation is working hard to empower its citizens and take control of what’s happening in their traditional territory — and that goes beyond the settlement land,” Tremblay said.

Traditional territory is land used by First Nations people for millennia for cultural purposes, but that doesn’t fall under modern treaties like settlement lands. Na-Cho Nyäk Dun’s territory spans 162,456 square kilometres.

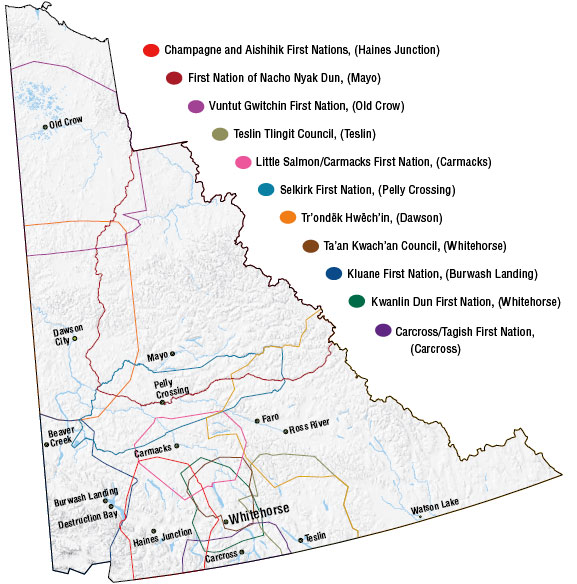

Traditional territory of Yukon First Nations. Map: Government of Canada

On traditional territory, pickers aren’t required to have permission from the First Nation, though the nation does play a significant role in the planning and management of the land and holds rights to traditional harvesting.

Tremblay said the Forest Foods partnership has led to more education surrounding the makeup of the First Nation’s lands and inherent rights in the area — to hunt, fish and forage medicinal plants, for example — and passing this information along has led to some outside foragers leaving on their own accord.

“It’s looking better now than one month ago,” Tremblay said.

But her optimism is tempered by the very real prospect that the rush for mushrooms isn’t going to end overnight.

“We believe there’s always going to be more (foragers from outside Yukon) because it’s a huge traditional territory,” Tremblay said. “We know there are still people out there.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

From investigative reporting to stunning photography, we’ve been recognized with four 2024 CAJ Awards nods...

The Narwhal is expanding its reach on video platforms like YouTube and TikTok. First up?...

Locals in the small community of Arborg worry a new Indigenous-led protected area plan would...