Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

Almost 20,000 Chinook salmon expected to cross the Alaska border into Yukon this summer likely won’t make it — a situation that has prompted an advisory committee to urge nearly all First Nations in the territory to refrain from fishing the species for the rest of the year.

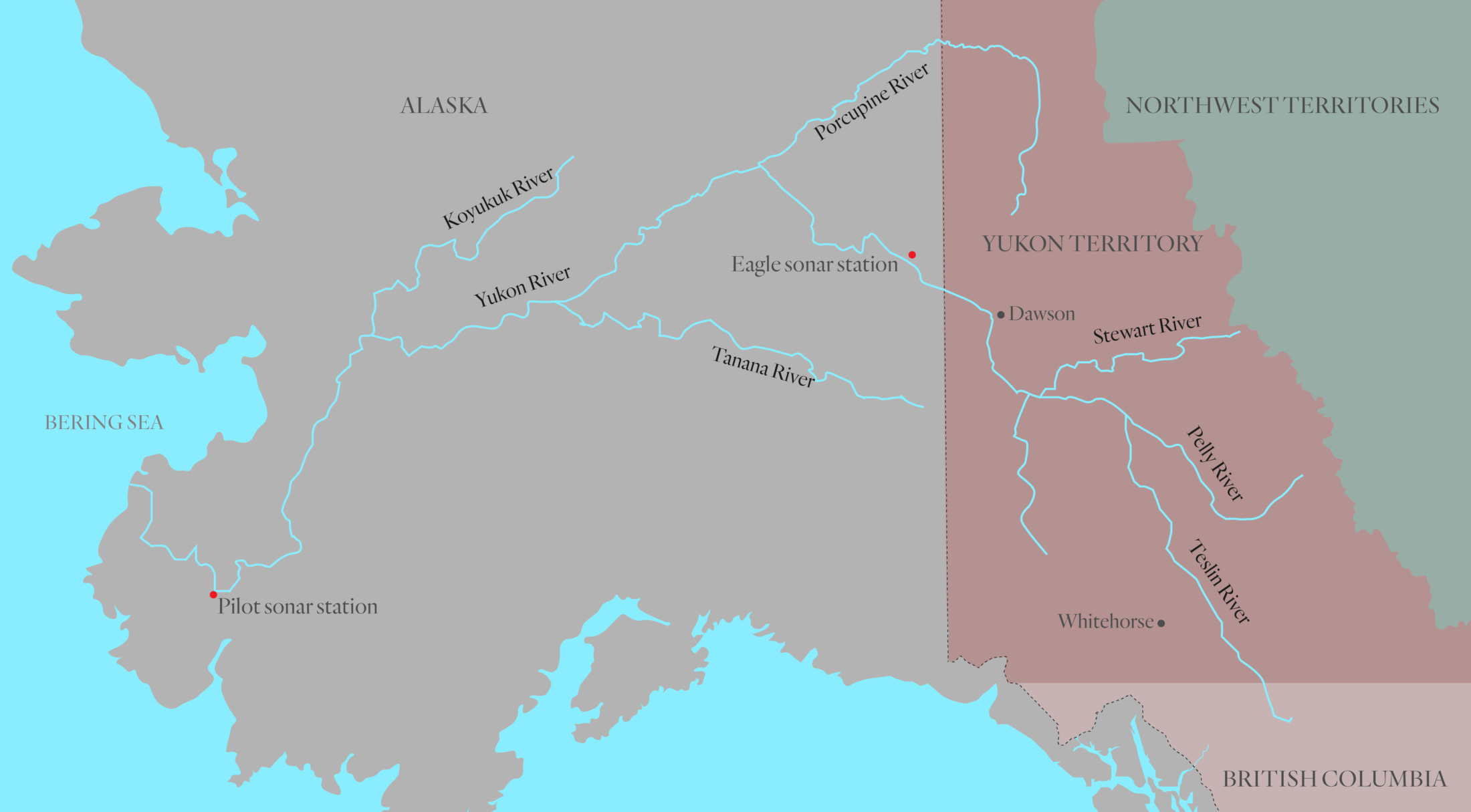

Based on sonar counts at Pilot Station, Alaska, about 77,000 Canadian-origin salmon were projected to be in the Yukon River this year, said Holly Carroll, summer season Yukon area manager with Alaska’s Department of Fish and Game. But as of Aug. 12, just 29,570 Chinook had swam past the next sonar station, located near Eagle, Alaska, about 30 kilometres from the Yukon border. It takes about one month for Chinook to swim from Pilot Station to Eagle.

“The information at Pilot suggested a Canadian-origin Chinook run of about 77,000, which would translate to approximately 50,000 Chinook at the border but those numbers aren’t materializing at the Eagle sonar,” said Steve Smith, manager of treaties, fisheries and salmon enhancement for the Yukon River at Fisheries and Oceans Canada.

This summer, 77,000 Canadian-origin Chinook salmon passed Pilot Station, Alaska, while only 29,570 fish have made it as far as Eagle, near the Yukon border. This is well below the minimum treaty-obligated escapement goal for Chinook salmon in Yukon of 42,500. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Chinook are now at the tail end of their run in the Yukon River drainage area, a migration that started some 3,000 kilometres away at the mouth of the river on the coast. By early September, the run should be over.

As well as being far below Alaska’s predicted return, current counts also fall about 10,000 fish short of a U.S.-Canada treaty-obligated goal of between 42,500 and 55,000 fish crossing into the territory. The annual average by Aug. 12 is 55,017 salmon.

Last year, roughly 42,000 fish passed the Eagle sonar station — about 500 short of the minimum goal.

Carroll said it would be “impossible” for Alaskans to have harvested the roughly 40,000 fish that never made it into the territory.

State fisheries were managed very conservatively this year, she said, with multiple closures on Chinook salmon fishing.

“There’s no way that we harvested that many,” Carroll said. “Most fishermen, on top of these restrictions, reported doing really poorly on their harvests because of super high water on the Alaska side.”

“Now, we’re wondering if there’s some sort of en route mortality that’s occurring that we just don’t know how to measure or what would be causing it.”

The department will conduct harvest surveys this fall, she said, which will lift the curtain on just how many Chinook were harvested this season.

“When you fail to meet the goal by over 10,000 fish, that’s not great — that’s terrible,” Carroll said.

“We are always endeavouring to get that harvest share to Canadian fishermen.”

Of the 14 First Nations in Yukon, 13 are affected by the request by the Yukon Salmon Sub-committee to halt all fishing for the rest of the year. Following the guidance is voluntary, as the sub-committee isn’t a regulator, but First Nations are strongly urged to stop fishing. The recommendation only applies to members of First Nations because they are the only people currently allowed to fish for Chinook on the Yukon River.

“I’m terribly discouraged by it,” said Al von Finster, vice-chair of the sub-committee, an advisory body independent of government. “I would much prefer there were more salmon in the river and those salmon could be harvested by the First Nations.”

Since Chinook salmon migrate through U.S. waters first, Alaska is obligated to take measures, such as fishing closures, to see that goal reached, von Finster said. But there is no penalty under the treaty for not meeting that goal.

“We were hoping for a late run,” he said, noting that additional conservation efforts, such as reducing the size of nets, were called for in Yukon earlier this summer. “Unfortunately, the run continued to fall.”

While somewhat of a guessing game, there are a few factors that could explain why so few fish made it into Yukon this summer.

There was exceptionally high water this year in the river as a result of precipitation and snowpack, von Finster said.

“That’s what those fish have to migrate upstream through and that delays them,” he said. “If their health is a bit dodgy, they may not make it. I think some of the fish basically ran out of steam.”

Chinook salmon migrate some 3,000 kilometres up the Yukon River from the Alaskan coast to spawn in Yukon territory. Kevin Cass / Shutterstock

There was also a patch of warm water when Chinook salmon entered the Yukon River from the Bering Sea, von Finster said, which could slow their progress on the long migration.

“If they are entering areas of warm water, what they may end up doing is holding in that water until the cool parts of the day. They will not migrate so quickly.”

A parasitic disease could also help explain the decline, said von Finster. Some Chinook could have picked up ichthyophonus, which attacks vital organs such as the heart.

“The fish simply can’t make it,” von Finster said. “They lose energy and they die.”

Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation is entitled to 750 Chinook salmon per year, according to its final agreement, which was established in the 1990s along with the nation’s land claims, with the federal and territorial governments. Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm said citizens have been harvesting half that for years already, recognizing the dwindling numbers of salmon crossing the border from Alaska.

Tizya-Tramm, said the federal government needs to do more to consult his community of Old Crow, which is located on the Porcupine River, a tributary of the Yukon River. If they listened to his people, he noted, perhaps there would have been more proactive conservation.

“It is not the southerners who are witnessing these real-time changes,” Tizya-Tramm told The Narwhal. “I question how they are going to address the trajectory of our changing climate, which is already happening with the lowering number of salmon. We need more partnership and more meaningful engagement. Their best bet beyond their sonars are our traditional people who are seeing … the changes.”

Tizya-Tramm said he reached out to Fisheries and Oceans Canada earlier this year, telling officials that their approach to managing Chinook isn’t working, and that Yukon First Nations can’t be expected to do all the work.

“They need to see the severity of changes for the salmon and our people, the slumping, the warming and occlusion of waters,” he said. “They need to see that all of this adds up to more loss, they need to realize the urgency we do.”

Smith with Fisheries and Oceans Canada said there’s always an opportunity to better consult First Nations.

“In a typical year we are welcomed by the people of Old Crow where we share back and forth information about the salmon runs,” he said. “This year took a turn for everyone with the onset of COVID-19.”

Tizya-Tramm said Chinook salmon are a mainstay of Gwich’in culture. If fishing can’t happen, cultural teachings won’t either.

“When First Nations cease to fish, we are cutting future generations off from their cultural practices and our relationship with these animals. As a Chief, it is the hardest thing to do to tell my people that they cannot fish Chinook out of our waters like their grandfathers and their grandmothers and people before them. This is to feed our families, and our children should always be allowed to taste salmon to keep our roots, our blood and our lands strong.”

“They’re asking our families not to eat.”

Updated at 5 p.m. on Aug. 14, 2020, to add comment from Fisheries and Oceans Canada, clarifying that only 50,000 Chinook salmon were expected at the Canadian border, not 77,000 as previously stated. Based on sonar readings at Pilot Station, Alaska, 77,000 Canadian-origin salmon were projected to be in the Yukon River this year, but not all of those fish were expected to make it to the Canadian border.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...