Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

On Thursday, a joint review panel — representing the federal and Alberta governments — released its recommendations on whether a massive new open-pit mine in the oilsands should proceed.

It recommended Teck’s Frontier Mine get the green light, despite finding it will have significant and permanent impacts on the environment.

The decision now moves to Minister of Environment and Climate Change, Catherine Mckenna, who has until February to issue a decision.

Environmental concerns flagged by the panel include the removal of old-growth forests, the destruction or permanent alteration of fish habitat, the release of a large amount of carbon pollution and the loss of wetlands and areas of “high species diversity potential.”

But, overall, the panel found these impacts were outweighed by economic benefits, saying “the project is in the public interest.”

Here are 10 things you need to know about this proposed new mine.

The Frontier mine would be the furthest north in the oilsands, just 25 kilometres south of Wood Buffalo National Park. It would cover 24,000-hectares (roughly double the size of the City of Vancouver) and would produce 260,000 barrels of bitumen each day at its peak, making it one of the largest oilsands mines — if not the largest — to ever be built in Alberta. This would take up about half of the additional volume created by the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion.

Bison in Wood Buffalo National Park. Photo: Louis Bockner / Sierra Club BC

The mine is expected to have a 41-year lifespan, taking us to 2081 by the time it’s completely shut down. By then, scientists have predicted that climate change will have already had far-reaching effects on Alberta — including dramatically shifting the average temperatures in Canadian cities.

At the Paris climate conference in 2015, Canada reaffirmed its target of reducing greenhouse gas emissions by 30 per cent (compared to 2005 levels) by 2030 and by 80 per cent by 2050.

What that means in reality is that the entire country can emit 150 megatonnes of emissions by 2050. The Teck Frontier mine is expected to produce four megatonnes per year, equal to three per cent of all of the emissions allowed in Canada in 2050.

“The oilsands are Canada’s fastest-growing source of emissions,” Gordon Laxer, a political economist and professor emeritus at the University of Alberta, told The Narwhal last fall. “Their growth is going to make it virtually impossible to meet our 2030 Paris climate targets.”

Last fall, The Narwhal asked Jeff Rubin, former chief economist with CIBC World Markets and a senior fellow at the Centre for International Governance Innovation, whether new oilsands mines make sense in the face of global climate change and changing world demand for oil.

Rubin told The Narwhal that meeting climate commitments “would require not only do we not see business-as-usual growth in world oil demand … but that we would see anywhere from a 20 to 50 per cent decline in world oil demand over the next 30 to 40 years, which would shut-in productions in places like the oilsands … because their cost of production would no longer be supported by oil prices.”

“If the world does avert the worst consequences of climate change, whether that’s 1.5 or 2 degrees, we’re going to see a significant reduction in world oil demand,” Rubin said.

Teck’s Frontier mine is proposing operations through 2066.

The area where the proposed mine will be built is wild — wetlands, peatlands and forests of jackpine, aspen, spruce and poplar. Some of these forests are over a century old.

Approximately 2,598 hectares of these old-growth forests will be removed for the mine to be built.

Old-growth takes a long time to re-establish itself, even with extensive reclamation efforts, because it’s, um, old.

The panel’s report says “there may be a loss of habitat for many species reliant on such forests, including species at risk, for at least 100 years following closure in 2081.”

In projections for the economic benefits of the project, the company used “an average long-term real oil price of US$95 per barrel for West Texas Intermediate” — a price not seen since 2014 — to calculate its base case for the economic impact of the project.

“Prices are forecast to be US$80 to US$90 per barrel by 2020, and increasing thereafter,” Teck said in a 2016 submission.

In its low-price scenario, Teck assumed an average WTI price of $76.51 per barrel and a high-price scenario of $115 per barrel. As of this writing, the price for WTI crude oil was under $60 per barrel — and has only reached $75 once since November 2014.

“The panel understands that there is considerable uncertainty regarding forecasts for future oil prices,” the report states. Nevertheless, the panel reiterated Teck’s prediction that the project will yield “$55 billion to Alberta in taxes and royalties.”

“The Frontier project will provide significant economic benefits for the region, Alberta, and Canada,” the panel concluded.

It seems Teck has its own doubts about whether the project makes economic sense.

The company’s 2018 annual report, released this February, says “there is uncertainty that it will be commercially viable to produce any portion of the resources” to be mined at the proposed Frontier site.

Other oil executives have expressed similar sentiments. At the Fort Hills grand opening, now-retired Suncor chief executive Steve Williams told reporters that “it’s unlikely there will be projects of this type of scale again.”

According to the review panel’s findings, wetlands cover nearly 45 per cent of the area studied, amounting to 14,000 hectares.

The Frontier project will remove all wetlands from the project development area, something the panel acknowledged is likely not reversible. “A substantial amount of wetland and old-growth forest habitat will be lost entirely or lost for an extended period as a result of the Frontier project,” the panel’s report states.

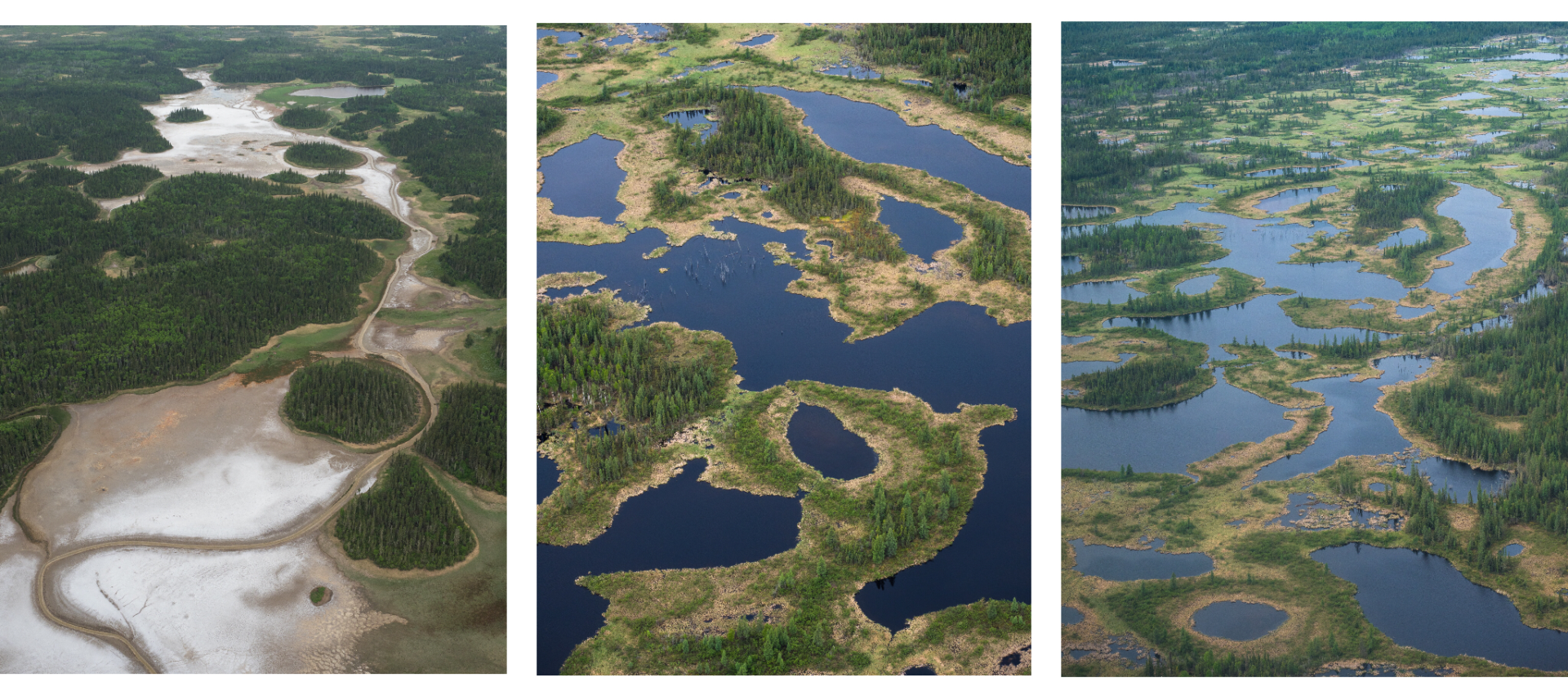

Far left: Wood Buffalo National Park salt plains. Centre and right: Aerial view of Wood Buffalo National Park’s famed wetlands. Photo: Louis Bockner / Sierra Club BC

The loss of this amount of these areas is an impact the panel describes as “a high-magnitude and irreversible project effect.”

The ability of companies to pay for cleanup once resources have been extracted has ignited a debate over mind-boggling environmental liabilities in recent years — and whether taxpayers might ultimately end up footing the bill.

“There are uncertainties associated with final reclamation outcomes.”

The panel’s report highlights some of the difficulties associated with Teck’s reclamation plans.

“Some habitat types cannot be reclaimed (e.g., peatlands),” the report states.

Over 3,000 hectares of peatland will be destroyed by the mine’s construction — “an irreversible loss” according to the panel’s report — accounting for 10 per cent of the project area.

The report also warns that cleanup may take a long time for sensitive areas, noting “reclamation will not occur or be complete for many years.”

In its report, the panel acknowledges the long-term cleanup is not guaranteed, though it also writes “this is expected at this stage of the process.”

“There are uncertainties associated with final reclamation outcomes,” the panel wrote.

The Frontier mine would be the second major foray into the oilsands for Vancouver-based Teck Resources.

The company has coal, zinc and copper operations across North and South America, but recently made its big debut in the Alberta oilsands with a 21 per cent interest in the Fort Hills Energy Limited Partnership, which owns the Fort Hills open-pit mine.

Fort Hills had its grand opening last fall.

Teck says on its website that “responsible environmental management is an integral part of who we are as a company,” but the company has faced criticism for its environment record in the past. Last winter, The Narwhal investigated long-term selenium pollution at one of the company’s B.C. operations.

Teck was one of three companies that voluntarily gave up leases on crown land earlier this year so that a new wildland provincial park could be created in the area.

The 161,880-hectare Kitaskino Nuwenene Wildland Provincial Park was created in response to requests from Mikisew Cree First Nation to allow for a buffer zone around Wood Buffalo National Park. The new wildland provincial park will allow for traditional activities to continue without the threat of further oilsands encroachment.

Wildland provincial parks are less developed than provincial parks, and the government of Alberta says on its website that Kitaskino Nuwenene Wildland Provincial Park will enable Alberta to contribute to the largest contiguous boreal protected area in the world.

Part of Teck’s submission rests on the idea that the Frontier mine will be “best-in-class.”

Teck told The Narwhal last fall that it “will have a lower carbon intensity than about half of the oil currently refined in the United States.” Documents filed by the company claim the “project represents best-in-class for greenhouse gas emissions from oilsands developments.”

But in Environment and Climate Change Canada’s submission to the review panel, the agency wrote that “while Teck indicates its intent to make the Frontier Mine project best-in-class with respect to [greenhouse gas] emissions intensity, it is in fact 24 per cent more carbon intensive on a per-barrel basis than the best project.”

Jan Gorski, an analyst with the Pembina Institute, told The Narwhal last fall that “projects that are anything but best in class shouldn’t be approved.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...