Meet Andrew Munroe, The Narwhal’s web developer

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

Coastal GasLink paid $171,000 to kill wolves in the range of an endangered caribou herd that will lose critical habitat to the company’s pipeline for a gas export project, The Narwhal has learned.

The money for a winter wolf cull in Hart Ranges caribou habitat, northeast of Prince George, was part of $1.5 million the B.C. government required Coastal GasLink to pay for “caribou and predator monitoring” — a condition for receiving a provincial environmental assessment certificate for its 670-kilometre pipeline.

Construction of the pipeline, which will supply fracked gas from northeast B.C. for the LNG Canada project, will remove or disturb 2,750 hectares of habitat for the Hart Ranges herd, eliminating old-growth forest the government had set aside for the herd’s recovery and also cutting through two designated caribou migration corridors, according to project documents.

Chris Johnson, an ecology professor at the University of Northern British Columbia who sits on committees advising the federal government on caribou recovery, said it’s the first time he’s heard of a corporation paying for a predator kill in B.C. to compensate for destroying the habitat of an endangered species.

“There are all sorts of ethical questions about killing wolves to save caribou, although the science clearly shows that the method does work,” Johnson told The Narwhal.

“Those ethical questions are made even more challenging by having industry pay for the wolf kill.”

Charlotte Dawe, conservation and policy campaigner for the environmental group Wilderness Committee, which has mapped the destruction of caribou critical habitat in B.C., called Coastal GasLink’s financing of the winter wolf cull “shocking and disturbing.”

“It’s incredibly problematic,” Dawe said in an interview. “If we begin to accept money like that, I worry about the future of all species that are at risk. If this sets a precedent — where industry is now able to pay money for governments to partake in really unethical and not effective solutions to recover species at risk — it’s a dangerous road to go down.”

Last September, the provincial Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development proposed a two-year predator cull in the habitat of Hart Ranges southern mountain caribou and two other at-risk herds.

The ministry said more than more than 80 per cent of wolves had to be exterminated to reverse steep caribou declines.

Human disturbances, including oil and gas development, have given natural predators such as wolves easy access to caribou whose habitat has been destroyed or fragmented right across Canada, with disastrous consequences for the once-robust species that evolved to spread out on unfractured landscapes.

Flagging tape marks the route of TC Energy’s Coastal GasLink pipeline, which cuts a wide swath through critical habitat for the endangered Hart Ranges caribou herd in the Anzac River drainage. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The Hart Ranges herd — which consists of two subpopulations known as the Parsnip and the Hart South — fell from an estimated 600 animals in 2010 to 375 in 2016, according to a YouTube video produced by the B.C. government, which has not released updated herd figures.

Johnson said while the Coastal GasLink project is only the latest industrial project to have a negative impact on the Hart Ranges herd, it represents a worrying trend of continued habitat loss and habitat degradation.

Despite the 38 per cent drop in population, the Hart Ranges herd is by far the largest of B.C.’s 10 remaining deep-snow caribou herds. Eight other deep-snow herds have become locally extinct in B.C. over the past decade.

Deep-snow caribou live in regions where snow is piled too high to paw through, forcing them to rely on arboreal lichens, which only grow in abundance in old-growth forests. Other southern mountain caribou populations can paw through snow to reach terrestrial lichens.

David Silver, the chair in business and professional ethics at the University of British Columbia’s Sauder School of Business, said the protection of animals and ecosystems and the development of the economy are all important values.

“When economic development threatens animals and ecosystems, difficult decisions must often be made regarding priorities,” Silver told The Narwhal. “Sometimes one can find ways to proceed with the economic activity and mitigate the harm to animals and ecosystems. In this case the ‘solution’ comes at the expense of the wolves.”

Silver said whether or not killing wolves is an ethically defensible outcome depends on how the decision to proceed in this manner was made and whether it was made by democratically elected, informed representatives “free of illegitimate pressure or influence on the part of the company or industry.”

The decision to oblige Coastal GasLink, a subsidiary of TC Energy (formerly TransCanada Pipelines), to pay the provincial government to monitor caribou and their predators was made in 2014 by the previous BC Liberal government.

Coastal GasLink subsequently donated more than $17,000 to the BC Liberal Party between 2015 and 2017, according to Election BC’s political contributions database.

Its parent company, TransCanada Pipelines Ltd., donated more than $135,000 to the BC Liberal Party from 2005 to 2016 and close to $14,000 to the BC NDP between 2012 and 2017.

In granting Coastal GasLink an environmental assessment certificate, former environment minister Mary Polak and former minister of natural gas development Rich Coleman said the project would have no significant adverse effects, “except with respect to caribou and greenhouse gas emissions.”

The pipeline corridor would generate “significant residual adverse effects” for caribou, due to habitat loss and fragmentation, as well as increased access for humans and predators, the ministers said in their decision statement, noting the project would negatively affect management and conservation objectives for at-risk caribou.

“…the success of proposed mitigation is uncertain and the project is likely to negatively impact caribou recovery objectives,” the ministers stated.

A view of the endangered Hart Ranges herd’s critical habitat in the Anzac valley north of Prince George. In 2019, the B.C. forests ministry issued 78 new logging cut block permits in the herd’s critical habitat, including six cut blocks in the Anzac valley. The cumulative impacts of industrial development, including forestry and oil and gas, spell trouble for caribou herds like the Hart Ranges. Photo: Taylor Roades / The Narwhal

The Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development confirmed in an email that Coastal GasLink contributed $559,800 to “caribou recovery and management efforts” over the past fiscal year, which ended on March 31.

The bulk of the funds went to the Hart Ranges herd, including $35,000 to capture and collar wolves, said the ministry, which also confirmed Coastal GasLink spent $171,184 on predator management to meet wolf density populations of less than three wolves per 1,000 square kilometres in the Hart Ranges herd habitat.

Last fall, the provincial NDP government asked hunters not to kill wolves with GPS radio collars, saying the effectiveness of wolf pack reduction — which typically involves shooting wolves from helicopters — would increase with more collared wolves alive on the landscape.

“When collared wolves are removed from their pack, the capability to reduce wolf numbers is significantly diminished, as packs can no longer be located quickly and efficiently reduced,” explained a ministry document for hunters.

The ministry said 91 wolves were killed during the winter in Hart Ranges herd habitat. About $300,000 had been budgeted for predator control from the Coastal GasLink funds this past winter, but not all the money was needed, and the unspent $129,000 will go back into the “caribou and predator monitoring” fund, the ministry said.

Coastal GasLink also paid $48,000 to collect data on new Hart Ranges caribou calves and their survival, $30,000 to access mortality sites to determine the cause of death in adult female caribou, $42,000 to collar caribou during helicopter captures, $10,000 for a birthing estimate model and to estimate births, and $10,000 to “initiate wildlife habitat area development for calving, rutting, connectivity and mineral licks,” according to the ministry.

The remaining $20,000 Coastal GasLink contributed during the past fiscal year went to the Telkwa herd in the Skeena region for mortality investigations, a fall census, a calf recruitment survey and collaring, the ministry said.

The Telkwa herd, which had 26 animals in 2018, will lose 245 hectares of habitat to the pipeline, according to a report from the B.C. Environmental Assessment Office. The pipeline will also disturb 334 additional hectares of the herd’s habitat, including in a proposed wildlife habitat area, a provincial designation meant to conserve critical habitat.

Coastal GasLink did not respond to a request for comment.

Human disturbances on the landscape make it far easier for wolves to prey on caribou. The logging of old-growth forests, on which caribou depend for nutritious lichen, their only winter food, soon brings a flush of growth. The greenery in newly open areas attracts moose and deer, which are followed by wolves. Photo: Patricia van Casteren / Flickr

Johnson said many British Columbians are under the misguided assumption that wolf culls are a necessary evil.

“It can be effective in reversing the decline of caribou populations that are suffering unsustainable mortality from predators such as wolves,” he said.

But wolf control will only be effective in the long-term if it is accompanied by strong efforts to conserve caribou habitat, including reductions in activities responsible for increasing wolf distribution and abundance, Johnson said.

New habitat protections for six imperilled southern mountain caribou herds in B.C.’s Peace region were recently announced by the B.C. government as part of a landmark partnership agreement with local First Nations.

Yet there are no new meaningful habitat protections for dozens of other highly endangered caribou herds in the province, including the Hart Ranges herd, even though all of B.C.’s southern mountain caribou herds are facing local extinction.

Last year, two more herds in B.C. became extirpated, or locally extinct, including the transboundary Gray Ghost herd that migrated back and forth from the Kootenays in southeast B.C. to the United States.

In a long-awaited move, last fall the Trump administration listed 17 imperilled B.C. populations of southern mountain caribou under the U.S. Endangered Species Act, including the Gray Ghost herd and the Hart Ranges herd.

The designation protects 12,000 hectares of critical habitat in Idaho and Washington so the species can eventually be reintroduced south of the border, where the demise of the Gray Ghost herd — also known as the South Selkirk herd — spelled the disappearance of caribou from the contiguous United States.

Johnson said wolf culls are only effective if they eliminate 70 to 80 per cent of the wolves in caribou range and take place every single year.

“We simply can’t do that forever,” he pointed out. “Wolf cull is supposed to be a stop gap approach to give some of those populations a chance to recover and also to implement other strategies that are going to minimize the effects of wolves on caribou populations.”

“The concern is how many years are we going to engage in wolf control and what are we going to do so we don’t get caught in this endless loop of very aggressive wolf control?”

Dawe said wolf culls should only occur in tandem with sufficient habitat protection, habitat restoration and emergency recovery efforts, such as penning pregnant caribou until their calves are old enough to stand a higher chance of survival in the wild.

“If all of those measures are happening and caribou are still being picked off at an unsustainable rate, that is the only way you should even be discussing a wolf cull.”

“The B.C. government has just relied only on a wolf cull,” Dawe said. “And we continuously find ourselves in a situation where caribou habitat is being destroyed while wolves are being killed at the same time.”

Recovery of species at risk must be guided by scientists, “not by industry’s interests and industry’s pockets,” she said.

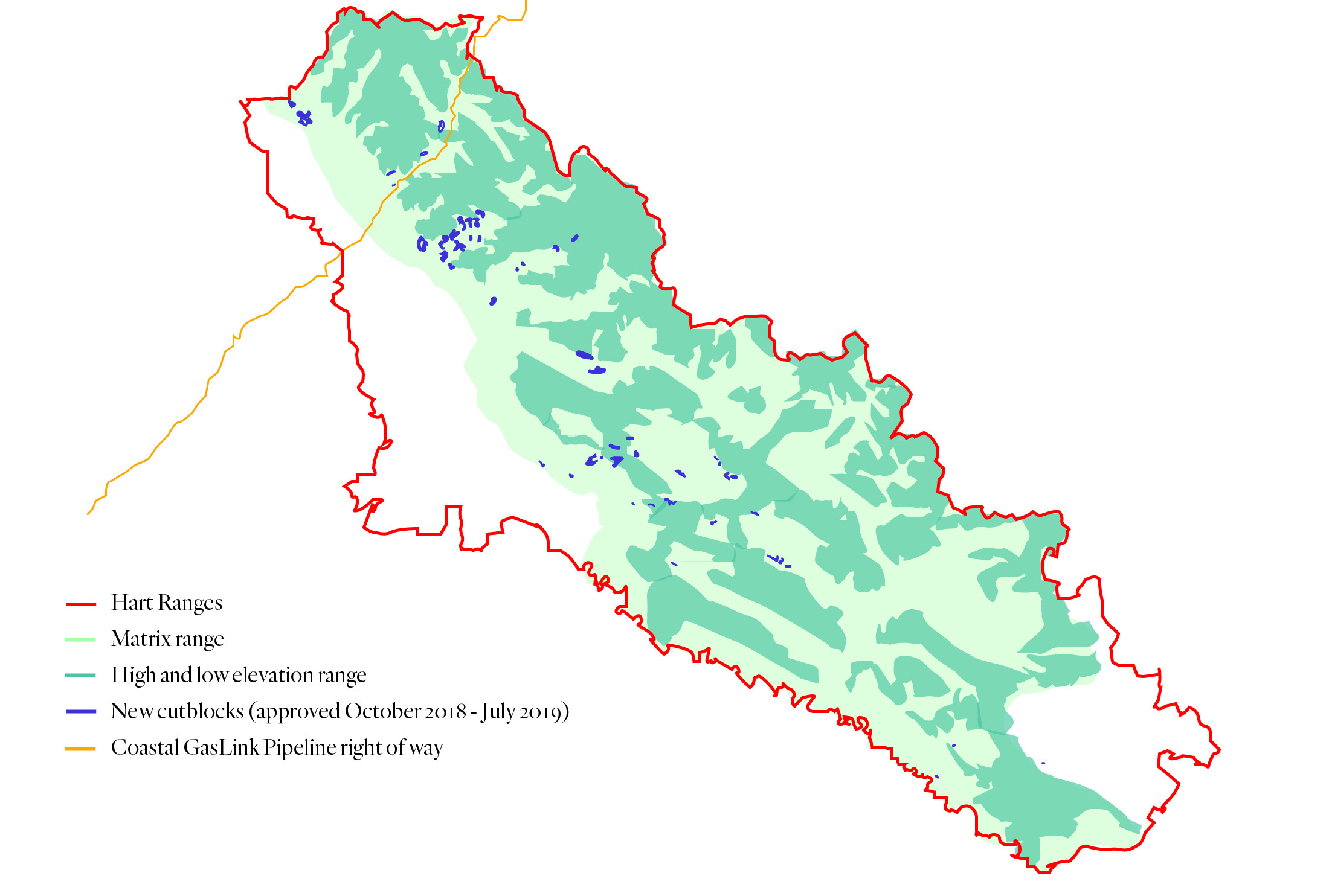

The Coastal GasLink pipeline is shown in yellow, cutting through critical habitat for the endangered Hart Ranges caribou herd. In addition to approving the pipeline in the herd’s habitat, the B.C. government granted permits for 22 new cutblocks between October 2018 and July 2019, according to data from the Wilderness Committee. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Dawe also said Coastal GasLink’s contribution of $65,000 for moose monitoring in Hart Ranges habitat this past year may also be a precursor to a moose cull.

When new roads are built and older forests are cut down for the pipeline — which will result in the clear-cutting or disturbance of 613 hectares of old forests, according to project documents — the areas will flush with new growth the following spring.

“That’s the type of food that moose love,” Dawe pointed out. “So the theory is that moose come in and start eating all this nice new growth and they follow paths into caribou habitat … and then wolves follow them in.”

“For this caribou sub-population to now have Coastal GasLink coming through [with] more disturbance in the way of a pipeline, roads to facilitate that, [and] logging, it’s going to make that number even worse and it’s going to put them further on the brink of extinction.”

Johnson said there’s no easy answer to the question of whether a wolf control program sponsored by industry is less desirable than a cull sponsored by the government.

“On one hand, we’re achieving the same outcomes regardless of who’s paying for it. On the other hand, industry may not want to align with something that’s as objectionable as predator control, or wolf control. Many people in the public have concerns about those types of activities.”

“The one big picture philosophical issue here is the company actually paying for this mitigating strategy,” he said. “Has it crossed some sort of line?”

“I don’t know where I sit yet but I do think it’s terribly interesting.”

U.S. lists B.C. caribou as endangered while province approves logging in critical habitat

Like what you’re reading? Sign up for The Narwhal’s free newsletter.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...

The Alberta premier’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free...