Meet Andrew Munroe, The Narwhal’s web developer

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

Some discomforts of the Yukon winter don’t last long — a car that just won’t start, a parka that’s frozen stiff. Others, however, carry over to following years.

The 2018-19 winter in Yukon was dry and frigid. Snowpack hit a near-historic low as a result, leading to low water levels in the reservoirs that drive the territory’s hydro electricity plants.

Because the territory’s grid is heavily reliant on hydro, Yukon Energy has been forced to use more diesel fuel this year.

Now, with climate change expected to make weather patterns even more volatile, the utility said it’s making moves to diversify the grid.

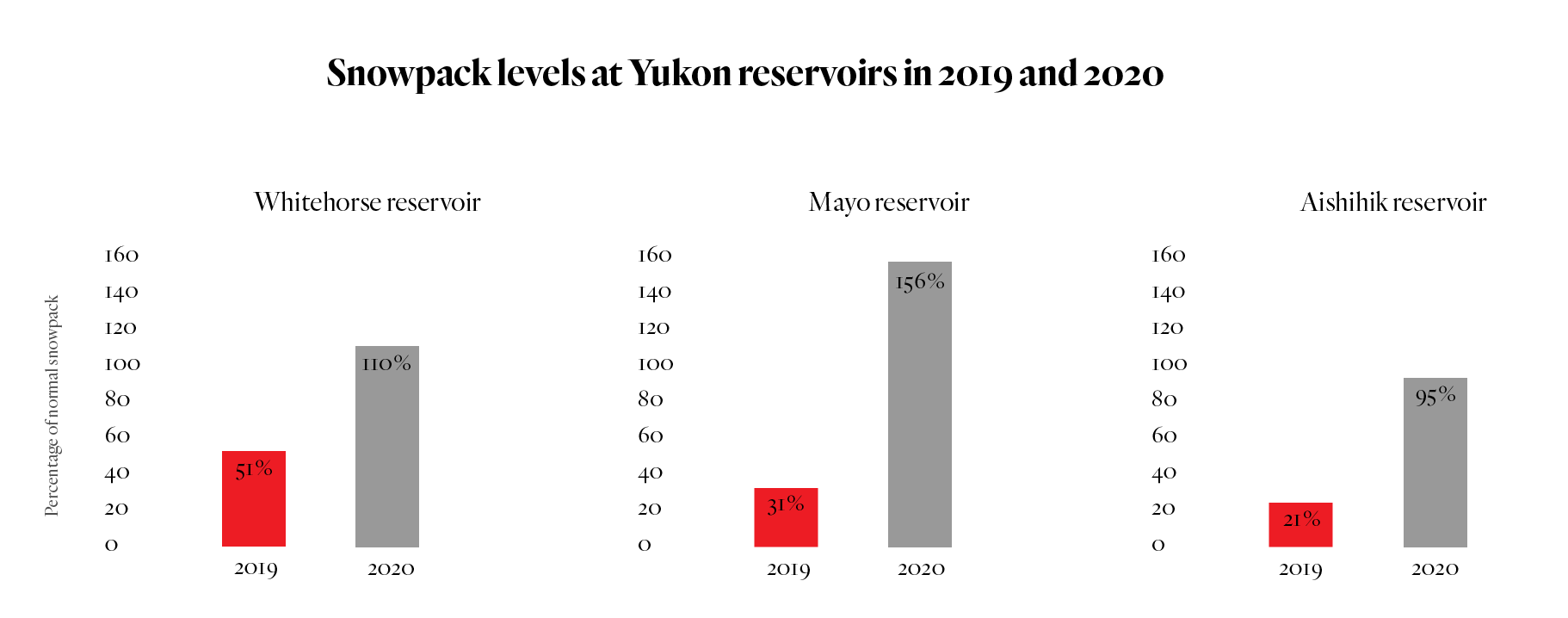

According to a Yukon Energy fact sheet, the Whitehorse reservoir had just 51 per cent of its normal snowpack levels in 2019.

The Mayo and Aishihik reservoirs fared much worse, with 31 per cent and 21 per cent of normal snowpack levels, respectively.

“The last time we had numbers like that was in the late ’90s,” said Andrew Hall, president and CEO of Yukon Energy. He added natural gas has been burning steadily since November to make up the difference.

And when an LNG generator broke down earlier this month, more diesel ended up being used to compensate for that lost capacity.

Snowpack levels influence the amount of running water available for hydro plants the following year. Source: Yukon Government. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Because of the lower water levels in the reservoirs, Yukon Energy estimates roughly 16.5 gigawatts of energy will need to be generated using fossil fuels in April and early May.

“That’s around the same amount of electricity 16,500 Yukon homes would use in a month,” the utility’s fact sheet states, “or about three per cent of the total amount of power we will likely need to generate this year.”

The sheet also notes 72 per cent of that power is being generated by natural gas, while diesel powers the rest.

Hall said climate change could actually mean more warm weather with higher levels of precipitation in the territory. But the problem is rainfall is hyperlocal, meaning Whitehorse may get a lot, while Carmacks, a roughly two-hour drive north, gets a fraction of it.

“It’s a variable we don’t have a good handle on,” he said.

The trick is to diversify the grid and look for efficiencies, according to Hall. And there’s a suite of things Yukon Energy is working on, in the near and long term, to do both.

Hall said an easy win when it comes to efficiency would be to update the Whitehorse dam’s turbine, which dates back to the 1950s.

But beyond that, Yukon is working to expand a program that enables residents to make money by generating wind, solar and biomass electricity and feeding it into the grid.

Hall said the Yukon government is in the process of doubling how much the cottage industry can produce by providing financial and technical support to First Nations and municipalities.

The territory will also introduce legislation to regulate geothermal development.

Yukon can also sync its grid with Atlin, B.C., where the Taku River Tlingit First Nation hopes to expand its hydroelectricity operations. The nation could provide the territory with upward of eight megawatts of power, Hall said. He added the project could be ready in roughly three years.

Since 2012, researchers at Yukon College, the Université du Québec and the University of Alberta have worked together with Yukon Energy to better predict water levels.

The hope is the research will help the utility better prepare for unanticipated weather patterns.

Brian Horton, manager of climate change research at Yukon College’s research centre, said there are five automated weather stations equipped with sensors that measure the depth and volume of the water in the snowpack at the headwaters of Yukon rivers.

The stations also use precipitation gauges to determine the levels of snow and rainfall.

The collected data, made available to Yukon Energy by satellite, can help determine seasonal forecasts and provide multi-decade projections, Horton said.

If Yukon Energy knows how much water is flowing, “they can make decisions on how they can operate the generating facilities within the envelope that they’re given,” he said. “This gives them more heads up, more planning capacity for knowing what’s available, what’s in the bank account, basically.”

But all this work comes with a caveat.

“You’re going to have, from time to time, these … drought years,” Hall said.

Developing a system that is 100 per cent renewable, even under drought conditions, is “just not realistic” for the territory, he added.

“There could be years in the future where we have similar situations where you have to run diesel just to keep the lights on.”

If anything is predictable, it’s that weather patterns will become less predictable with climate change.

Hall agrees, calling efforts to predict the weather a “crapshoot.” Case in point? The snowpack levels from the 2020 winter season that left the Whitehorse reservoir at 110 per cent.

Like what you’re reading? Sign up for The Narwhal’s free newsletter.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...

The Protecting Ontario by Unleashing Our Economy Act exempts industry from provincial regulations — putting...

The Alberta premier’s separation rhetoric has been driven by the oil- and secession- focused Free...