Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

On Tuesday, Finance Minister Bill Morneau announced the federal government will buy the existing Kinder Morgan Trans Mountain pipeline and pay for the construction of the new oilsands pipeline. In total, it’s expected to cost Canada between $15 billion and $20 billion to pull off.

But there’s an even larger oilsands-related cost on the horizon: the more than $48 billion that will be required to clean up the ever-growing tailings ponds.

In fact, only a week ago — on May 23 — the Alberta Energy Regulator approved two more tailings management plans, this time for mines owned by Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited, a wholly owned subsidiary of oilsands giant Canadian Natural Resources Limited.

That’s despite not knowing if the company will be able to clean up its tailings within this century, or what technology it plans to use, or what penalties the company will face if it fails.

In fact, the only thing the regulator appears to know definitively is that the volume of the company’s toxic tailings will skyrocket in coming decades, well past its supposed deadline for peaking and declining.

Due to clear “uncertainties and deficiencies” in the application, the Alberta Energy Regulator chose to only approve four to five years of tailings growth, requiring the company to submit amended applications in 2021 (for the Muskeg River Mine) and 2022 (for the Jackpine Mine). Think of it as a highly unusual grace period.

But Jodi McNeill, technical and policy analyst at Pembina Institute, expressed significant concern in an interview with The Narwhal that the approach of using “regulatory kid gloves” will only lock in a very risky future trajectory without any guarantee of treating tailings on time.

“We really would have liked to see the regulator be much more stringent about enforcing the regulations today so that we don’t end up in a situation where we’re locked in on a pathway that isn’t going to work,” McNeill said.

The latest approvals of the tailings plans followed the regulator’s controversial decisions to give the go-ahead to tailings expansion at Suncor’s Millenium Mine in October 2017 and Canadian Natural Resources Limited’s Horizon Mine in December 2017.

These approvals happened as part of the regulator’s ongoing attempt to implement Directive 085, the province’s latest tailings management framework, which is considerably weaker than the previous Directive 074 — which all companies failed to meet.

McNeill said all four of the plans approved under the “incredibly flexible and malleable” Directive 085 have been non-compliant. Uniquely, the two approvals of the Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited mines included graphic illustrations of how quickly tailings waste will grow in coming years and contravene the rules.

“The tailings profile itself blatantly doesn’t meet the requirements, which means they’re just not treating aggressively or fast enough,” she said. “The AER included a profile of what they proposed and what the actual requirements would be that they would have to meet. It’s visually telling.”

At the 155,000-barrel-per-day Muskeg River Mine, fluid tailings will increase from nine million cubic metres in 2015 to 69 million cubic metres in 2022: a sevenfold increase. That’s in addition to 92 million cubic metres of existing tailings.

The volume of new tailings at the Muskeg River oilsands mine. The solid blue line is what the Alberta Energy Regulator has approved. The dotted blue line is what the regulator wants Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited to do. The solid red line is what Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited is planning to do. Graph: AER.

As can be seen in the graphic, the regulator expects new tailings volume to peak at 69 million cubic metres and steadily decline to 43 million cubic metres in 2058, the mine’s end of life. From then, Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited has 10 years to get the new fluid tailings to “ready to reclaim” status — which the regulator defines as “processed with an accepted technology, placed in their final landscape position, and meet performance criteria.”

But Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited has very different plans.

In the company’s plans, rather than peak at 69 million cubic metres in 2022 as expected by the regulator, it proposed that tailings volume from the mine tops out at 127 million cubic metres in 2054. Without explaining how, the company then suggests it can rapidly reduce the volume to around 2017 levels, then take until 2115 to achieve completely “ready to return” status.

That’s 57 years late.

Meanwhile, the volume of new tailings at the 100,000 barrel per day Jackpine Mine will increase from 12 million cubic metres in 2015 to 26 million cubic metres in 2023, in addition to 22 million cubic metres of toxic waste that already exists.

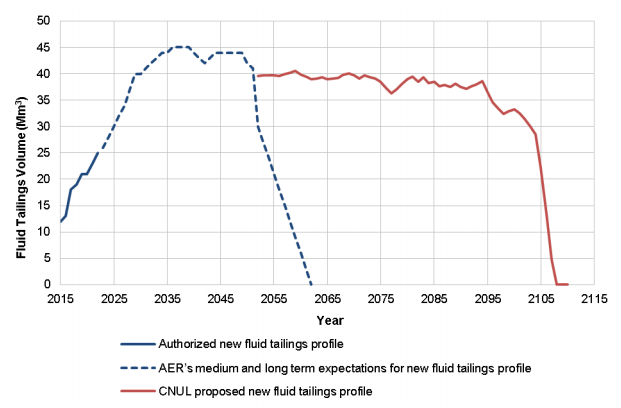

The volume of new tailings at the Jackpine oilsands mine. The solid blue line is what the Alberta Energy Regulator has approved. The dotted blue line is what the regulator wants Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited to do. The solid red line is what Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited is planning to do. Graph: AER.

Some of the new tailings generated at Jackpine will be sent to Muskeg River Mine for a process called “froth treatment.” This itself violates a previous regulatory decision as Shell, the previous owner of the mine, had pledged to build a froth treatment plant at Jackpine Mine rather than continuing to ship it to Muskeg River (those volumes are counted in the Muskeg River Mine’s tailings profile and account for the “long tail” of tailings at Muskeg after it closes).

In its approval, the regulator wrote about ongoing shipments of froth to Muskeg River: “All of this is inconsistent with what was proposed in the [Jackpine Mine] expansion applications.”

In total, the regulator expects Jackpine tailings will continue to increase to about 45 million cubic metres in 2038, after which it stabilizes and soon plummets to hit “ready to reclaim” status by 2062 (a decade after the closure of the mine). But Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited predicts that the mine will remain open until early next century, resulting in new fluid tailings remaining at between 35 million and 40 million cubic metres until 2095.

Keep in mind that the regulator hasn’t actually allowed Jackpine to operate until next century. But the approval is being assumed by the company. Canadian Natural Upgrading Limited did not respond to a request for comment.

The approvals also arrived only a few days after NAFTA’s Commission on Environmental Cooperation called for the three countries in the trade agreement — Canada, Mexico and the U.S. — to vote on if an investigation should be conducted about documented seepage from oilsands tailings into the Athabasca River and other water bodies.

The case was first submitted

in June 2017 by two environmental organizations and a Dene man. Jackpine Mine was specifically referenced in the submission. It quoted from a 2004 Joint Panel Report of the project that “some seepage would discharge to the ground surface between the tailings area and Jackpine Creek and that half of this seepage would enter the creek.”

The countries are required to hold a vote by July 20.

There’s also mounting concern about who’s actually going to pay for the cleanup of oilsands tailings. According to Environmental Defence, there’s currently 1.4 billion cubic metres of tailings waste that will require at least $48 billion to restore.

As of September 2017, the regulator only held $939 million in cash deposits and credit guarantees from oilsands companies for that task.

The remainder is expected to be paid off in the last 15 years of the mine’s life. But in 2015, Alberta’s auditor general warned: “If an abrupt financial and operational decline were to occur in the oilsands sector it would likely be difficult for an oilsands mine operator to provide this security even if the need for the security was identified through the program.”

Despite that, the provincial government still hasn’t changed requirements to guarantee payments of tailings reclamation costs since the oil price crash.

McNeill said that Pembina has been waiting on the release of the AER’s decision on Syncrude’s Aurora North Mine since February. She said that Aurora North is one of the “worst performers” when it comes to tailings management, with its plan including the sleuthing of tailings and a pit about half a kilometre from the Athabasca River.

She said the length of time that has passed since when the decision was expected and now may suggest that the regulator will get a “little more stringent because the plan was just so egregious.”

But based on the four plans that have approved so far, it’s not looking good.

“Ponds are going to continue growing, outcomes continue to be risky and uncertain,” McNeill concluded. “We see it as a really big shame that this is the outcome that we’re getting ultimately from this directive and from this policy framework. The fiscal and environmental risks are enormous.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...