Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

Alberta’s new ban on “mountaintop-removal” coal mining has very limited, if any, applications in reality, The Narwhal has learned. According to a spokesperson for the Alberta government, the definition of the term is extremely narrow and does not apply unless the top of a mountain is “completely” removed.

The province’s ongoing coal saga reached a new peak earlier this month when Energy Minister Sonya Savage took to the podium to reinstate the same 1976 coal policy her government had quietly rescinded last spring. She was apologetic. She outlined the public outcry her government had heard in response to its decision to scrap the policy that had protected large swaths of the eastern slopes of the Rocky Mountains from surface coal mining, much of which would be for metallurgical (or steel-making) coal.

She said the government would “do better.”

“Rescinding [the coal] policy has caused tremendous fear and anxiety that Alberta’s majestic eastern slopes would be forever damaged by mountaintop and open-pit coal mining,” she said. “Let me be clear. This will not happen in Alberta.”

She told reporters she had issued a directive to the Alberta Energy Regulator that, in addition to reinstating the categories of land as defined in the 1976 coal policy, also included direction to prohibit mountaintop-removal mining.

On that point she was clear. “We’ve put an outright ban on mountaintop mining,” she said. “That will never be allowed in Alberta.”

These statements, as it turned out, came with a few caveats.

First, Savage was referring only to what’s known as Category 2 land. That does cover a substantial portion of the eastern slopes, but it doesn’t include areas like where the Grassy Mountain mine is proposed.

And second, it turns out the definition of “mountaintop removal” is more narrow than the average Albertan might have been inclined to believe.

The Narwhal asked the Alberta Energy Regulator and the premier’s office for their definitions of mountain-top removal mining. “Mountaintop removal and open-pit mining are different methods of surface mining,” spokespeople for both said by email.

Mountaintop-removal, they both added, refers to when a mine “completely removes the top of a mountain.”

Alberta Energy Minister Sonya Savage announced an “outright ban” on mountaintop-removal coal mining in early February. Now, the premier’s office and the Alberta Energy Regulator have confirmed to The Narwhal that the narrow definition of this type of mining does not apply to any past, present or proposed coal mines in the province. Photo: Government of Alberta / Flickr

The Narwhal asked the Alberta Energy Regulator if there has ever been a coal mine in Alberta that fits its definition of a mountaintop-removal coal mine. “We have not identified any historical mines in Alberta that meet the definition for mountaintop removal,” a spokesperson said by email, noting “we are also not aware of any future projects in Category 2 lands that may involve mountaintop removal.”

Kavi Bal, the director of strategic planning in the premier’s office, told The Narwhal by email that, in Alberta, “there are no historic or current mountaintop removal developments, and we are not aware of any future projects.”

That left some wondering what exactly the ban was … banning.

Derek Apel, a professor in the School of Mining and Petroleum Engineering at the University of Alberta, told The Narwhal the government’s ban lacks clarity. The government, he said, needs to be “more precise with specifying what mountaintop-removal mining is or what definition they are going to use.”

It’s what Lars Sander-Green, mining lead at conservation organization Wildsight, said amounts to the government “trying to split some hairs” when it comes to vocabulary.

Apel said the government’s definition leaves a lot of room for other mining types to move forward in the mountains. “Obviously if they use a definition as it is defined in Appalachia — that the whole top of the mountain has to be removed and there’s this overburden that has to go to the valley and the whole area has to be flattened — that’s very easy to bypass,” he said.

Sander-Green is concerned that regardless of the vocabulary used, allowing any kind of surface coal mines to proceed in the Rockies will have significant ecological impacts.

“I think what [the Alberta government] is trying to do here is pretend that they’re giving folks what they want,” Sander-Green told The Narwhal.

The government, he said, is “trying to make a really fine difference between whether you remove half a mountain or three-quarters of a mountain or a whole mountain.”

The term “mountaintop-removal mining” first appeared in the Appalachian Mountains, which extend across the eastern United States, where coal formations are different than those in the Rockies and call for a different method of extraction.

There, according to Apel, coal formations — known as seams — are more often horizontal. They are the results of ancient settling that formed layers within the mountains. And the Appalachian Mountains, unlike the Rockies, were largely shaped by erosion. Essentially, coal seams were formed and covered, remaining horizontal.

In the Appalachians, companies remove the top of a mountain to expose layers of large, flat coal seams.

As Apel explains, in the Rockies, the situation is different. The Rockies were formed more recently by dramatic heaving and folding, as a result of tectonic movement. So while coal seams were once horizontal, many now run at an incline — diagonally or even vertically.

Therefore, it often makes more sense for companies to dig down the seam — in essence, making an open pit — and remove the coal as they dig deeper and deeper. According to the spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator, “open-pit mines are excavated downwards from the surface in increments referred to as benches.”

Apel said it’s unlikely that there are horizontal seams in the Canadian Rockies. “It’s going to be rare,” he said.

In an email, a spokesperson for the Alberta Energy Regulator told The Narwhal that mountaintop-removal mining is not common in Alberta. “Due to the severe geologic faulting, folding and structural variability in the eastern slopes of the Rockies, the surface coal mines in Alberta’s eastern slopes are typically developed using open-pit mining methods,” she said.

And in her directive to the Alberta Energy Regulator, Minister Savage did not ban open-pit mining.

The two coals mines the furthest along in the process of applying to start operations in Alberta’s eastern slopes are Tent Mountain and Grassy Mountain. Both of those are billed as open-pit mines and are on Category 4 land, which does not prohibit surface mining.

Open-pit mining involves removing layers of soil and rock — referred to as overburden — to access coal seams below.

Spokespeople for the premier’s office and the province’s energy regulator both told The Narwhal by email that mountaintop removal involves removing “overburden,” in this case the top of a mountain, “in order to access a targeted coal seam, whereas open-pit mining is more selective in overburden removal practices.”

The term mountaintop-removal mining is avoided by industry in Canada. “If you were to look at open-pit coal mining in B.C., this type of mining would not be referred to by [the] coal-mining industry as mountaintop removal,” Apel told The Narwhal.

Instead, he said, open-pit mines can be located near the tops of mountains. Even if half of the mountain was removed, “it would not be called mountaintop removal.”

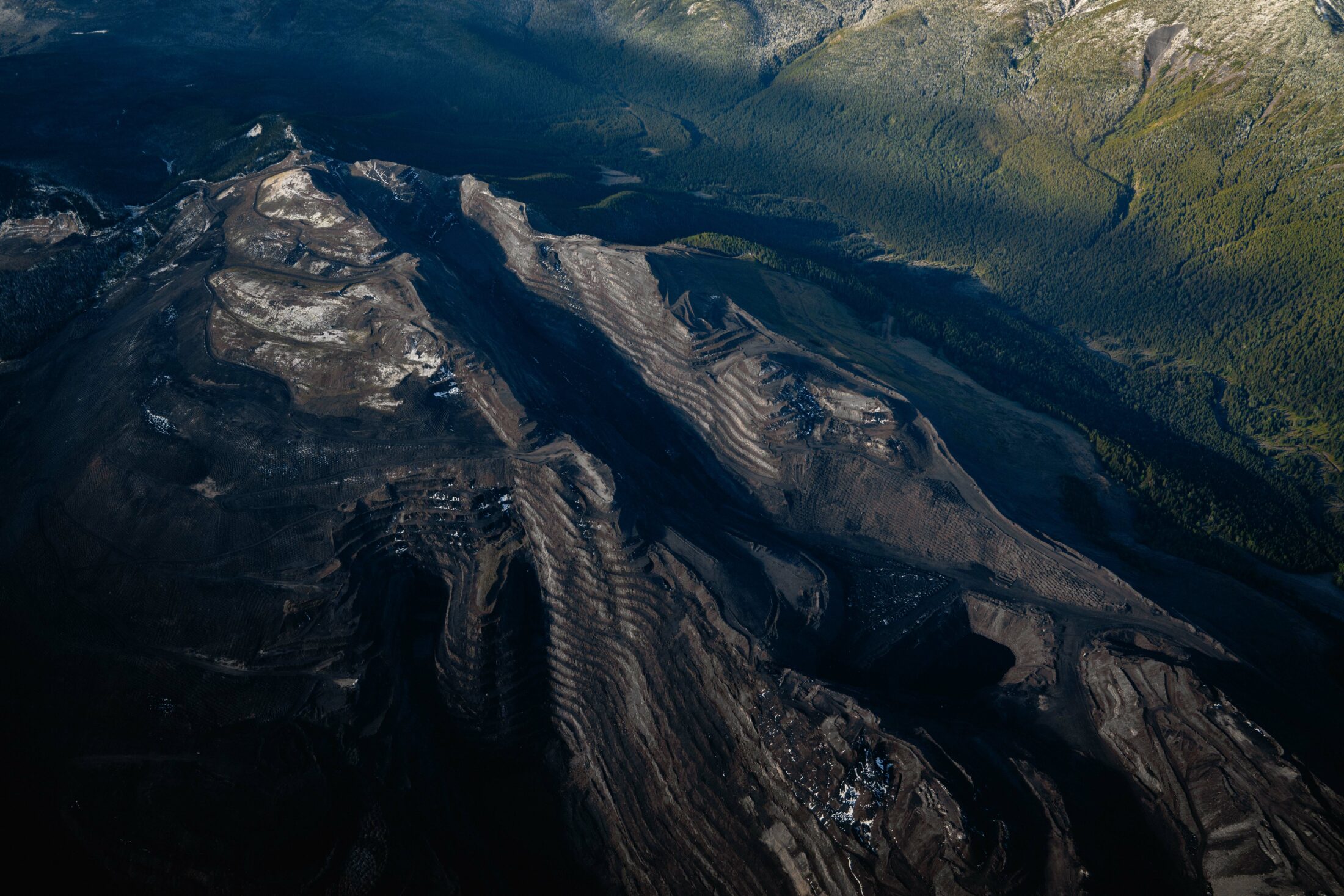

Teck Resources says its four metallurgical coal mines in B.C.’s Elk Valley, including the mine shown here, are open-pit mines. Alberta Energy Minister Sonya Savage has banned “mountaintop-removal” coal mines, but not open-pit mines. Photo: Callum Gunn

A spokesperson for Teck Resources confirmed to The Narwhal that Teck’s four metallurgical coal operations in B.C.’s Elk Valley are open-pit mines. These mines are often cited as examples of mountaintop-removal mining by the public, advocacy groups and media outlets, including The Narwhal.

“Whatever you want to call it, the goal is always to remove the coal while shifting as little overburden as possible,” Sander-Green told The Narwhal. “So, if the coal is underneath the peak of a mountain, then you’ll remove the mountain to get at it. If you can get at the coal from the side of a mountain, then you’ll do that because moving rock is very expensive.”

All of Teck Resources’ mining operations in B.C.’s Elk Valley are defined as an open-pit mines, even though members of the public commonly refer to these kinds of projects as involving mountaintop removal. Photo: Callum Gunn

There are already open-pit mining projects proposed in the Rocky Mountains in Alberta. One of those is Australia-based Montem Resources’ Tent Mountain project.

Mining began on the Tent Mountain project in the 1940s and was suspended in 1983. Montem wants to restart the mine, which will cover 750 hectares near Coleman, Alta., and produce coal for 14 years. The mine is described as an “open-pit surface coal mine” in company documents.

Photos and video on the company website show the existing open-pit mine to be very near the top of a mountain.

Montem Resources did not respond to The Narwhal’s request for information.

When a company uses open-pit mining techniques, what’s known as overburden still must be removed. The resulting piles, known as waste rock, can be the source of leaching contaminants.

As Apel explains, waste rock can leach selenium and ammonium nitrate. The latter is the result of the explosives used to “crack the overburden.”

Selenium is naturally occuring in some coal deposits. It becomes a concern when concentrations are elevated in waste rock piles. Teck Resources has invested hundreds of millions of dollars in trying to contain its selenium issues in the Elk Valley, but elevated selenium levels in the area have led to concerns about fish and drinking water.

Open-pit mining and mountain-top removal mining both involve hauling away part of a mountain, known as overburden, to be stored in waste rock piles, seen here. Waste rock piles can leach pollutants like selenium and ammonium nitrate. Photo: Callum Gunn

B.C.’s water quality guidelines recommend selenium levels stay below two parts per billion and limit selenium in drinking water to 10 parts per billion. As The Narwhal has previously reported, selenium levels in Elk Valley rivers directly downstream from Teck’s mines have reached 50 or 100 parts per billion. A 2013 study found selenium levels in rivers directly upstream of these mines were far lower, at one part per billion.

In January, a retired Alberta government official shared previously unreleased data with the Canadian Press showing selenium levels downstream of coal mines in the province were “consistently above the water quality guidelines and in many cases way higher.”

Despite the government’s narrow definition of mountaintop-removal mining, there are indications that the general public’s understanding is much more broad.

According to Alberta’s definitions, the Grassy Mountain coal mine in southwestern Alberta will be an open-pit coal mine. But that didn’t stop hundreds of concerned members of the public from submitting comments about mountaintop removal mining techniques to the joint review panel tasked with preparing recommendations on whether or not the project should continue.

Some commenters conflated the two different terms, writing “I am commenting to express my disapproval of the Grassy Mountain open pit/mountaintop-removal mine” and “that in 2021 we are even contemplating approving mountaintop-removal open-strip mining for coal is frankly extraordinary. This method of mining is incredibly destructive to the environment.”

Others specified they were opposed to mountaintop-removal mining, but appeared to be under the impression Grassy Mountain would use that technique. “I am writing to express opposition to the proposed mining of coal using mountaintop removal techniques,” wrote one commenter. “Please, do not allow this project, or any future mountaintop coal mining in the eastern slopes, to move forward,” wrote another.

Katie Morrison, conservation director with the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, told The Narwhal she doesn’t think Albertans are concerned about the nuances in industry vocabulary.

“I don’t think that Albertans are concerned about that technical difference,” she said.

“I think they’re concerned about the massive impact that open-pit mining has on the Rockies, no matter what you call it in name.”

Apel suggested there are alternative methods of mining that could be used to reach metallurgical coal in areas of ecological, cultural and recreational importance like the eastern slopes of the Rockies.

The government, he said, should be investing in research to explore mining techniques that could significantly reduce the environmental impact of metallurgical coal.

“We’re not going to eliminate the usage of metallurgical coal, not only in the near future, [but] for a long time,” he said. Metallurgical coal is used in the production of steel, which Apel pointed out is important for the manufacturing of technologies part of an energy transition, like wind turbines and electric cars.

Despite hundreds of millions of dollars invested by Teck Resources for water treatment facilities at its Elk Valley mines in B.C., selenium levels in the area are still elevated far above government guidelines. High levels of selenium have led to concerns about drinking water and fish populations. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

One technique, called high-wall mining, he said, could reduce the footprint of a mine on the surface. In this type of mining, equipment tunnels into a coal seam without removing the soil and rock above.

In promotional videos online, manufacturers boast that the equipment can mine 300 metres into the ground, with no workers needed underground.

Morrison has concerns about underground mining. Just because it’s underground, she said, “doesn’t mean that it has zero impact in the region.”

“We’re still talking about potential disruption to groundwater systems through tunnels through rock and coal seams,” Morrison told The Narwhal.

“Just because it is mostly underground doesn’t mean there’s no impact on the top. If there are roads and access points and tunnels and air shafts … all of these pieces would still be on the landscape.”

On Tuesday, Savage announced that a public consultation on a new coal policy would begin at the end of March. In the accompanying news release, the government reiterated its promise that “no mountaintop removal will be permitted.”

In the meantime, exploration programs already underway can continue in the eastern slopes, and proposed open-pit mines in the Rockies are still making their way through regulatory processes.

That leaves Morrison concerned about the government’s ban, which she said gave “false hope or false promises” to Albertans.

Sander-Green echoed that sentiment, saying the government’s narrow definition of the mining technique it has banned suggests the government is “trying to play some games” when it comes to vocabulary.

Update Mar 12, 2021 at 10:00 a.m. MT: This article was updated to include links to the full written responses from the premier’s office and the Alberta Energy Regulator, provided in response to media inquiries from The Narwhal.

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...