Water determines the Great Lakes Region’s economic future

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

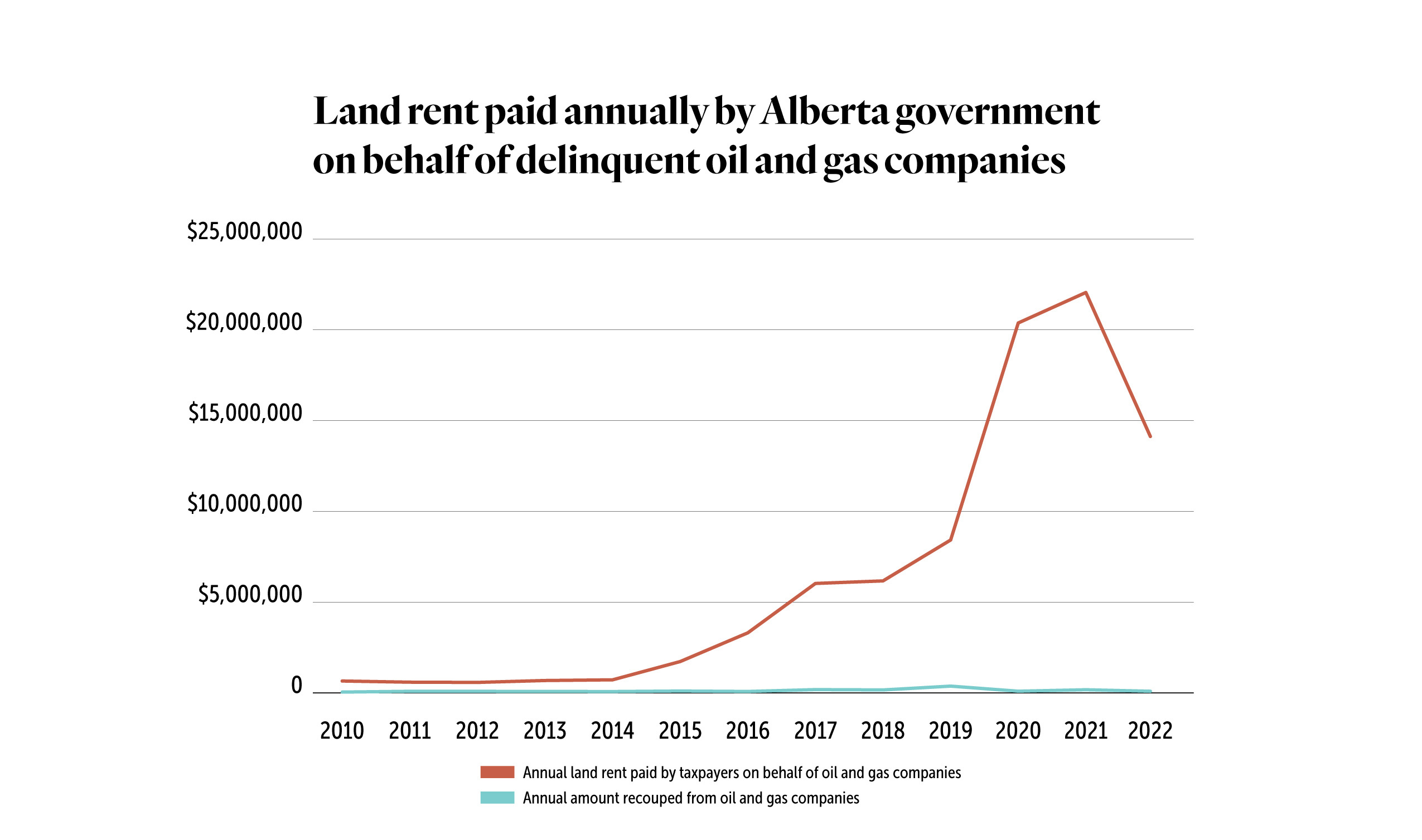

The Alberta government paid $14 million to landowners last year on behalf of oil and gas companies that couldn’t — or wouldn’t — pay their rent.

The province only recouped a little less than $28,000 of the $14 million through debt collection — less than half of one per cent — according to figures obtained through a freedom of information request.

Companies are required to pay rental payments to landowners whose land they are using for oil and gas activity, whether to drill a well or install another related facility. When they don’t pay, the tab is footed by taxpayers.

The total is down from a high of $22 million the previous year, but well above the average of $6.5 million paid out over the past 13 years, according to data from the Land and Property Rights Tribunal, an independent tribunal that handles landowner claims for land rent (until 2021, such payments were overseen by the Surface Rights Board).

When oil and gas companies fail to pay rent on the land leased for exploration, landowners can apply to the tribunal to have those rents paid for by the province.

A total of 4,882 landowners petitioned the tribunal in 2022, with 3,231 receiving compensation, also down from the previous year.

“In 2022, the number of applications submitted was more typical of what we expect to receive in a year,” Mike Hartfield, a spokesperson for the tribunal, said by email. “The Land and Property Rights Tribunal has observed more operator payments to landowners than in previous years, which may explain why there was a reduction in the volume of applications received in 2022.”

That reduction is relative.

The number of claims for payments, and the amounts paid, started to climb after 2014 when a prolonged price downturn hit the patch. Data from the tribunal shows figures below $1 million every year between 2010 and 2014, followed by three years of twofold increases.

The figures then jumped significantly between 2019 and 2020 as the pandemic struck, from approximately $8 million to $20 million, and has remained high even as companies reap record-setting profits.

There has also been less money recouped through government debt collection after 2019, with three years straight where less than one half of a percent was recovered.

“The important moments here, of course, are 2015 onwards, and if you compare the 2022 numbers to anything back then it’s still outrageously bad,” Shaun Fluker, an associate professor of law at the University of Calgary, said in an interview.

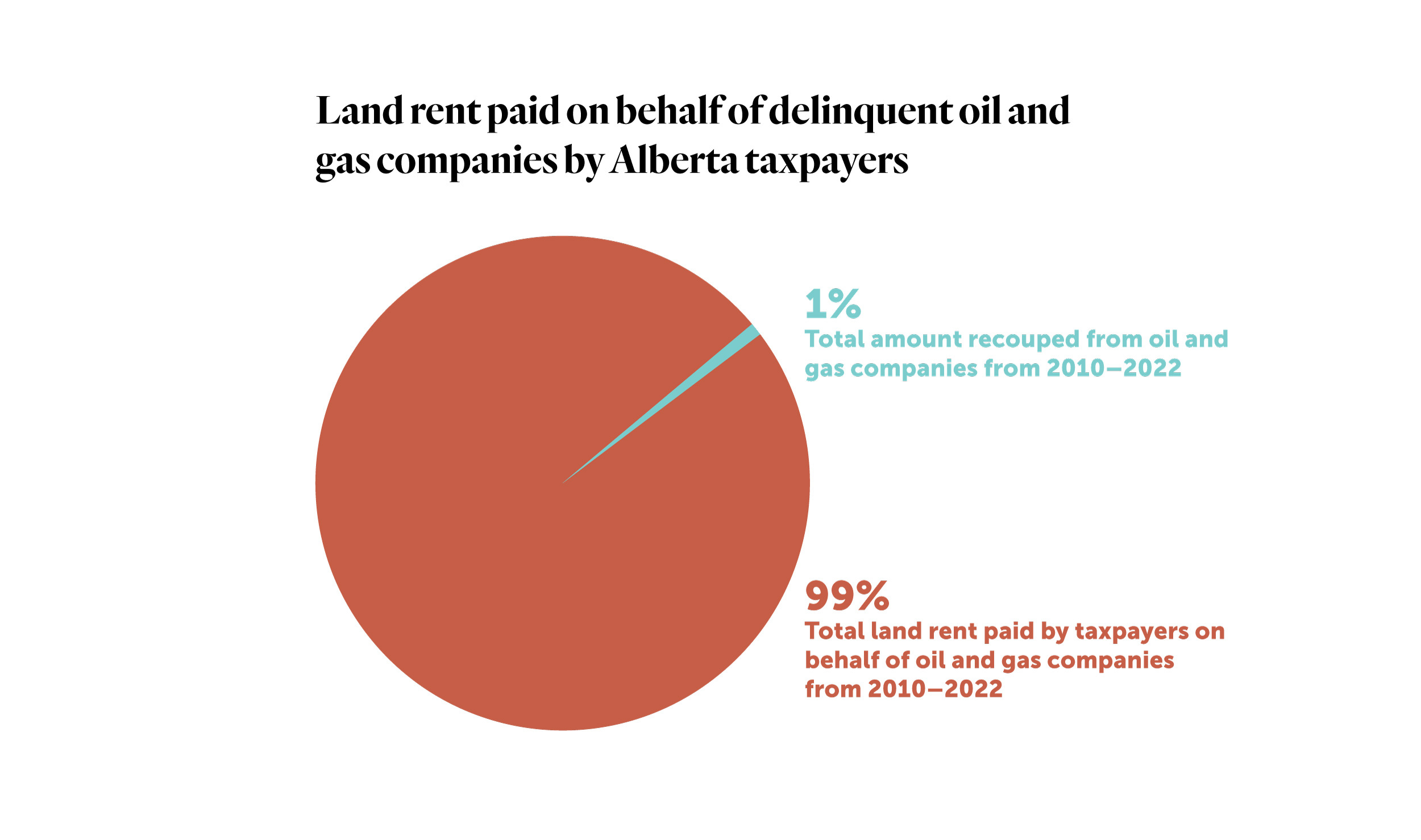

Since 2010, the government has paid almost $86 million in lease payments to landowners, according to data from the tribunal. Approximately $762,000 — less than one per cent — of that has been recouped from companies.

Landowners in Alberta can’t refuse access to their property for oil and gas exploration and must negotiate a contract with a company that compensates them for the loss of land. Under the province’s Surface Rights Act, landowners can apply to the tribunal to recover their money if a company stops paying.

The tribunal identifies the well owners and anyone with a working interest and issues a demand to pay. If no payment is made, the tribunal has the power to suspend access to the site. And if payment still isn’t made, it can direct the government to pay the landowner on the company’s behalf.

“This may be to pay the full amount owed or a different amount,” Mackenzie Blyth, press secretary for the minister of municipal affairs, wrote in an email to The Narwhal on behalf of the government. “The review may also conclude in a decision to decline to direct the minister to make the payment.”

That process has resulted in backlogs over the years, with landowners complaining of long wait times for compensation, but Hartfield said the tribunal has been working to address the issue.

In this year’s budget, the tribunal received an additional $800,000 to hire more part-time members to reduce decision times, he said. It has also moved away from a “paper-based process to electronic,” implemented online submissions and other efficiencies.

Hartfield said decision timelines should be reduced to a maximum of 90 days for most routine applications by the fall of 2023 with the additional funding.

In 2022, 66 per cent of applications to the tribunal resulted in payouts, in line with the average number of paid claims since 2010, but those percentages vary widely from year to year. The highest percentage of paid claims was in 2020 at 89 per cent, and the lowest was 2016, with 35 per cent.

Fluker from the University of Calgary said the process isn’t always so straightforward for landowners. Companies can dispute bills and prolong a process that, for them, is familiar and routine.

When there’s a dispute, the 90-day window for compensation does not apply.

Almost 44 per cent of applicants did not receive compensation in 2022. Hartfield says the reasons are varied, and include withdrawal of applications because a company settled their accounts, delays due to incomplete applications, dismissals due to insufficient information or complexities of the case.

Hartfield says examples of those complexities could include submissions or legal arguments from the operator, issues around the condition of the land and how it impacts loss of use and wills and estate concerns, among others issues.

That can put more pressure on landowners.

“It’s not a big deal for them to push something into a regulatory dispute process,” Fluker said. “For a landowner it’s a huge deal, not even just financially, it’s an emotional experience.”

Landowners have to assume the expense of any adversarial process with little to no help from the tribunal or the government, something that further exacerbates the resource disparity between an oil company and an individual, Fluker argues.

He said many likely don’t bother, or don’t know of the process and the number of wells with unpaid rent is likely higher than figures suggest.

Hartfield said the tribunal may use its discretion to ensure “reasonable costs” be paid to landowners from oil and gas companies, which could include legal and appraisal costs.

The issue of unpaid rent could also point to a lack of resources for the government to hold companies accountable, according to Janetta McKenzie, the acting director and senior analyst of oil and gas at the Pembina Institute.

“It very broadly shows that we need enforceable rules, because if the province is ending up having to pay out this money, this speaks to an issue in the system,” she said.

McKenzie said the system should compensate landowners if they’re losing out on rent payments, but it shouldn’t be “to the tune of tens of millions of dollars.”

It’s the result of a system that both McKenzie and Fluker agree was never supposed to handle so many failures.

“We seem to be focusing on procedures and processes that were never intended to be the dominant form of resolution,” Fluker said.

“They were designed to be the exception to the norm — a situation where despite someone’s best efforts things just didn’t work out.”

That extends beyond the issue of land rent to include rules and regulations around everything from unpaid municipal taxes to well closure, cleanup and reclamation.

It makes for a complex, and confusing, mix of regulatory failures that are often discussed and dealt with in silos.

“This topic gets tangled with the other issues,” Fluker said. “Surface compensation is one thing but a failure to reclaim or remediate is something completely different, and it’s not even part of this conversation,” Fluker said.

“That’s a completely different problem and a landowner has to deal with that too. And so it’s a real quagmire.”

The Alberta Energy Regulator has no authority when it comes to lease agreements between landowners and companies, which are private contracts. But it does say any information it receives regarding the financial health of a company or well could impact licence transfers.

“All transfer applications are privy to a 30-calendar-day public notice of application period on [the regulator’s website] in which concerns towards a potential licence transfer can be submitted, including those of a licencee’s financial health,” Teresa Broughton, a spokesperson for the regulator, said by email.

“The [regulator] considers all statements of concern submitted, when making decisions on applications.”

What the regulator does have authority over is the related, but separate, issue of unpaid municipal taxes owed by energy companies.

According to the Rural Municipalities of Alberta, as of 2023 its members are collectively owed $268 million in unpaid property taxes from oil and gas companies. A further $132 million of unpaid taxes has been written off by municipalities and an additional $45 million in taxes is owed through established repayment agreements.

The total amount is equal to $445 million.

Under new rules brought in this spring, the regulator can now block the transfer of licences or approval of new licences if a company owes more than $20,000 in taxes and does not have an approved payment plan in place with a municipality.

If it’s a transfer to a new company, the purchaser must prove payment of tax arrears is a condition of sale.

“Evidence must be in the form of a letter signed by a director or an officer of the company and contain a verbatim citation of the condition within the purchase and sale agreement,” Broughton said. “This letter should be provided at time of application and may be subject to an Alberta Energy Regulator audit.”

She said a similar process tied to the issue of lease payments to landowners will not be considered as it is “outside of our remit.”

Fluker doesn’t see a direct line between the soaring budgets of oil and gas companies and lease payments. The wells where rent is past-due likely aren’t producing untold barrels and the related profits.

If they were, companies would likely be working to keep them going and maintain access.

Keeping them going through government payouts, however, is likely exacerbating a larger, intertwined issue — closure and cleanup.

“I would guess that if we took all of these sites where surface lease payments are not being paid, we’d find a lot of so-called active sites that probably should be considered inactive and the regulator should be pushing for closure work on those things.”

A recent investigation by The Narwhal and CTV News revealed 80 per cent of reclaimed wells and 44 per cent of abandoned wells — permanently plugged but not yet reclaimed — have never produced oil or gas, leaving a mountain of more difficult, and more expensive, sites on the landscape.

There are currently around 75,000 inactive wells in the province.

Fluker argues landowners should have greater access to information about the companies which intend to work on their land and should be given greater rights to deal with problems if and when they arise — including a mechanism to be reimbursed for hiring contractors to clean up old wells.

“I think we’re left to sort of look at what is happening on the landscape generally, and rationally come to the conclusion that whatever they’re doing is not working,” he said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Climate change, geopolitics and business opportunities power a blue economy

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion