5 things to know about Winnipeg’s big sewage problem

115 billion litres, 70 years to fix, $5.5 billion in lawsuits

Note: This story contains images of illness and death.

I first met Warren Simpson in March of 2018, at a birthday party in Fort Chipewyan, Alta. He was soft-spoken, funny and sweet, and like so many others in Fort Chipewyan and Fort McKay, he had worked in the oilsands industry.

He had spent his childhood hunting, fishing and trapping, and graduated highschool in 1989. As an adult, he worked in the oilsands. “Basically I lived in camps,” he told me. He loved Chip, as the locals call it, and if he could have had a well-paying job there, he said, he would have stayed. His mother had lived there before she died; his sisters and brother were there. But he also loved his job and the lifestyle it had afforded him: a new Ford F-150 Platinum pickup truck, shopping for the latest designer clothes, trips to Montreal, to palm-lined beaches and to luxury hotels in the mountains.

Then he was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer — a cancer he believed was caused by his proximity to the oilsands.

Warren wasn’t alone in his suspicions. The community, home to approximately 1,200 Cree, Dene and Métis people who live a few hundred kilometres downriver from the oilsands, had already been ringing alarm bells for over a decade.

According to Alberta Health Services data from 2014, no cases of the rare cancer Warren had would be expected in the small community. The government’s data found at least three instances. Community members suspected more. Despite this, Alberta Health Services concluded “the total number of cancers and most types of cancers in the Fort Chipewyan area were the same as rates in the rest of Alberta.” A comprehensive federal study had been promised, but not completed.

Warren wanted to tell his story. He wrote about his experiences online, saying he wanted, “mostly to give awareness of so many damn cancers that we suffer in Fort Chipewyan … let’s pray for all the people with cancer.”

Warren’s cancer was terminal. He invited me to stay in his home during his final days, and so I was there, embedded as one of his own family. It was the end of 2019 — I had begun photographing Fort Chipewyan nine years earlier.

When I first traveled to Fort Chip in the fall of 2010, I thought I was doing a month-long story exploring the potential relationship between the oilsands and cancer cases in the region. On that first trip, most of the folks I spoke with brought up the generational trauma from the Holy Angels residential school, founded in 1874. Locals referred to it as “the mission.”

One of the first people I met was a Dene Elder named Alice Rigney, one of Warren’s aunts. Alice, her husband John Rigney and I stayed up all night out on the Athabasca Delta as she told me about surviving Holy Angels. “The mission really broke you. That was the start of the loss of my culture,” Alice told me. Alice and John described devastating conditions in town when the school finally shut down in 1974 — everyone was traumatized from generations of attendance at Holy Angels. The Truth and Reconciliation report in 2015 outlined the devastation across Canada: “Overwhelmed by [the residential school] legacy, many succumbed to despair and depression,” the authors wrote.

“Countless lives were lost to alcohol and drugs. Families were destroyed, children were displaced by the child welfare system. The survivors are not the only ones whose lives have been disrupted and scarred by the residential schools. The legacy has also profoundly affected their partners, their children, their grandchildren, their extended families and their communities. Children who were abused in the schools sometimes went on to abuse others. Some students developed addictions as a means of coping. Students who were treated and punished as prisoners in the schools sometimes graduated to real prisons.”

Just as residential schools left scars across Canada, so did the legacy of Holy Angels on Fort Chip. It was into this world that Warren was born, in 1969, as a member of the Mikisew Cree First Nation.

Meanwhile, Alberta’s oilsands were growing. Just two years before Warren’s birth, a company called Great Canadian Oil Sands (now Suncor Energy) began digging up the earth to mine for bitumen — the first large-scale commercial development in the region. As the size and number of oilsands mines increased, so too did the list of potential impacts on nearby communities. Warren told me Suncor was one of his employers, but Suncor did not respond to emailed questions or a request for an interview.

In 2006, Fort Chip’s former fly-in physician, Dr. John O’Connor, said publicly he believed oilsands mines and tailings ponds could be causing elevated rates of cancers in the local population. Dr. O’Connor implored all levels of government to study the issue.

Shortly after he came forward with his concerns, a group of Health Canada physicians filed complaints against O’Connor with the College of Physicians and Surgeons of Alberta, saying his statements hindered their credibility, hurt his patients and their community and were at least partly untrue. The investigation dragged on for two years, affecting his ability to serve and advocate for the people in Fort Chip. Ultimately, no penalty was issued: the College released a report saying “advocacy on behalf of the community of Fort Chipewyan is supported,” but that “advocacy [needs] to be fair, truthful, balanced and respectful.“ The College declined an interview with The Narwhal but noted “Dr. O’Connor’s public profile doesn’t state any disciplinary actions.”

Despite the accusations, O’Connor’s conclusions rang true with what people in Fort Chipewyan had already suspected — there were just too many cancers. Warren’s was yet another in a succession of diagnoses in the community: cervical cancer, biliary tract cancer, non-Hodgkin lymphoma. The list of community members with cancers and health problems continued to grow.

I spent several years returning to Fort Chip as well as Fort McKay and Fort McMurray to document the cultural, ecological and potential human health impacts of the oilsands.

In 2012, I photographed the wake and funeral of Layla, an infant girl who was stillborn, four months prematurely. Layla’s parents, Chelsea L’Hommecourt and Wade Noltcho, were devastated by the loss and chose to have a proper burial for their daughter. Layla’s parents lived in Fort McKay, where the sound of propane cannons from tailings ponds is constant, an unnatural hue glows in the sky and the smell of industrial toxins is ever-present.

Throughout her pregnancy, Chelsea’s home had been routinely enveloped in pollutants, including several volatile organic compounds, from the surrounding oilsands sites just a few kilometres away. Environment and Climate Change Canada data suggests these pollutants “are not of immediate concern,” but can have “significant” impacts in the long run. Previous studies have found developing fetuses are “particularly susceptible to environmental pollutants” and suggested exposure to air pollutants including particulate matter and carbon monoxide — both present in Fort McKay — may be linked to higher risks of babies being stillborn. There have been no studies or evidence directly linking air pollution in Fort McKay to birth defects.

Three years later, I once again connected with the L’Hommecourt family and met Layla’s half-brother Dez, who was born with a serious heart defect that required two separate open-heart surgeries before he turned seven. Though formally establishing causation is difficult, his family also believed there to be a direct link to the oilsands. Dez and Layla’s grandmother Jean L’Hommecourt had no doubt Layla’s premature birth and Dez’s heart defect were connected to pollution.

“My daughter never smoked when she was pregnant. She didn’t even drink coffee. She didn’t even drink soda pops or anything. And still my grandson was born with an underdeveloped heart,” L’hommecourt told me as she tried to contain her tears.

I was beginning to witness firsthand what people in Fort Chip and McKay had been saying for years: cases like Layla’s and Dez’s were not isolated incidents. But as Dr. O’Connor pointed out so long ago, there has yet to be a comprehensive health investigation in the community, despite promises made by the federal government.

“It’s never been studied,” O’Connor said of cancer rates in Fort Chip when I asked on a trip in 2019, noting there have been studies looking into adverse impacts of upstream mining on wildlife, fish and water. “The community lived so close to water — on water — and subsisted off the land and water. You can put two and two together. … But we need a scientific, comprehensive, unbiased study.”

“I’m wondering if there is a fear of what might be found,” O’Connor said of the reluctance to move forward with a baseline health study, adding industry was invited to be part of the management oversight committee of the study promised by the federal government.

The government cites a lack of agreement as the reason for the study’s delay. “Since 2009, many efforts have been undertaken to bring partners together to create a framework for the Fort Chipewyan regional baseline health study, but consensus has yet to be reached,” Nicolas Moquin, a spokesperson for Indigenous Services Canada, said in an emailed response to my questions (Health Canada referred all questions to the First Nations and Inuit Health Branch of Indigenous Services Canada. Neither agreed to an interview). “The department continues to support efforts to achieve consensus and remains willing to work with all partners to create this framework.”

When asked in a follow-up question whether industry was invited to the table, a spokesperson said the federal government’s partners are “namely the province and the First Nation,” and that the government “is committed to ensuring this work is led by First Nations.”

It’s now been 13 years since the federal study was first promised. In the meantime, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission released its report, new pipelines forged across Indigenous land, much of Fort McMurray burned in a wildfire, the footprint of the oilsands continued to expand — and Warren got sick.

My month-long cancer story had clearly become something infinitely larger.

Over a decade ago, the advocacy work of Fort Chip locals like Lionel Lepine, Eriel Derranger, George Poitras, Jada Voyageu and others sent a clear message: Canada’s colonization of Indigenous territories and the assimilation of Indigenous Peoples had never ended.

Dr. O’Connor and Indigenous leaders like Athabasca Chipewyan First Nation Chief Allan Adam worked to also convey that the health of Indigenous Peoples is intrinsically linked to their traditional cultural and spiritual identities — going “out on the land” is an empowering and therapeutic experience. Hunting, fishing and trapping, they implored, are not only ways to subsist, they are also sacred, spiritual practices. This is why Treaty 8 signatories pushed for the ability of Indigenous Peoples to hunt, fish and trap on their territories to be enshrined for “as long as the sun shines.”

The Dene of Fort Chip are colloquially known as the “caribou eaters” because they historically followed, and survived off of, caribou herds. When the Dene situated themselves at the fur trading post of Fort Chipewyan in the late 18th century, the caribou would visit them each year, oftentimes walking right through the middle of town. Elders told me that the last time caribou came through Fort Chipewyan was in the 1950s, long before Warren was born.

In the winter of 2019, I followed hunters from Fort Chipewyan approximately 300 kilometres into the Northwest Territories in search of the woodland caribou herds. The extreme remoteness and cold made the journey difficult, dangerous and costly for the hunters, most of whom came home to Fort Chip empty-handed. It was clear the impacts of industrial activity are complex and multi-faceted.

Fort Chip is not the only community to live alongside intense industrial activity. In the spring of 2019, I followed the Enbridge pipelines that carry heavy crude from the oilsands to the cluster of refineries that encircle the Anishinaabe community of Aamjiwnaang, near Sarnia, Ont. The region is colloquially known as “chemical valley,” and it is home to Canada’s most densely concentrated group of petrochemical refineries. So proud was the Government of Canada of these facilities that they added a photograph from chemical valley to the back of the $10 bill for the “Scenes of Canada” series in the 1970s and 1980s.

In Aamjiwnaang, I met Baskut Tuncak, then the United Nations special rapporteur on human rights and hazardous wastes. Tuncak toured around Aamjiwnaang, visiting homes, cemeteries, schools and playgrounds, all located within metres of refineries, pipelines and flare stacks. The scent of benzene — sweet and a bit like gasoline — and other known carcinogens was everywhere.

In Tuncak’s words, “the prevalence of discrimination in Canada’s laws and policies regarding hazardous substances and wastes is clear. There exists a pattern in Canada where marginalized groups, indigenous peoples in particular, find themselves on the wrong side of a toxic divide, subject to conditions that would not be acceptable elsewhere in Canada.”

“A natural environment conducive to the highest attainable standard of health is not treated as a right, but unfortunately for many in Canada today an elusive privilege,” he said.

In late 2019, Warren invited me back to Fort Chipewyan. I knew the reason for his request — and my heart sank. Months earlier, Warren had told me that he was dying from cholangiocarcinoma, or bile duct cancer, the extremely rare and aggressive cancer which had become unsettlingly common in his community.

In Canada, the incidence of bile duct and gall bladder cancers is 30.92 cases per one million people — 0.003 per cent. There were already at least three cases of bile duct cancer, a figure “higher than expected” in Fort Chip, according to the Alberta government’s 2014 report. When asked about updates to its data, Alberta Health Services referred The Narwhal to Alberta’s Ministry of Health, which did not respond to a request for an interview or emailed questions. When a spokesperson for Alberta Health Services was asked for a response for a third time, she wrote, “there have not been any new cases of cholangiocarcinoma in Fort Chipewyan registered since 2017,” and said cases of cholangiocarcinoma and other liver and bile duct cancers in the Wood Buffalo Region are monitored on a monthly basis, but the most recent report was delayed due to COVID-19.

When I asked Dr. O’Connor how many cases he knew about in Fort Chip, he told me there have been at least six, possibly seven, cases of cholangiocarcinoma in the community since 2004, a figure I confirmed with Debbie Sandberg, a nurse practitioner who has worked in the community on and off since 2002.

According to Alberta Health Services, the known risk factors of bile duct cancer are complicated, including family history, bile duct stones, cysts and abnormalities, liver cirrhosis, inflammatory bowel disease, aging, obesity, alcohol, diabetes and viral hepatitis — none of which appeared to be factors in Warren’s case, according to Dr. O’Connor.

Months before I arrived, Warren had told me “I want you to photograph my last breath.” That responsibility followed me home to Toronto and back again to Chip — it weighed more heavily when I arrived to find him emaciated, exhausted and experiencing constant pain and nausea. We had a couple good days together. We watched movies together in his room and talked a bit about his feelings regarding his illness:

As Warren declined into an increasingly delirious state, his mind wandered to various memories and dreams. His speech grew increasingly disassociated and formless. Family and friends opted to stay by him through the night instead of returning to their homes.

Everyone took shifts staying with him in or beside the bed. The kitchen became a refuge — a place for bottomless coffee and cigarettes next to the air-clearing whir of the range hood. As the morning light faded in on November 16, we all knew it was likely to be Warren’s last day on Earth. A Dene gospel CD made its 73rd repeat play. Coffee mugs piled up in the sink to be cleaned, only to become dirty again in a relentless cycle. Food was made but no one was hungry. Best friends flew in from the south. All of Fort Chip seemed to cram into the tiny bedroom to lay their hands on this man they loved.

As Warren’s breaths grew more laboured, an Elder named Rene Bruno came to recite the Hail Mary in Dene. The afternoon began to darken as the light left Warren’s eyes. At 3:04 p.m. on Nov. 16, 2019, just shy of Warren’s fiftieth birthday, the community of Fort Chipewyan lost a friend, a son, a brother, an uncle, a helping hand, a consistent joker — a loving, warm, musical soul.

Scientifically, logically, mathematically, Warren should not have died. He had a miniscule chance of contracting cholangiocarcinoma in his lifetime — but he did anyway, and so have others in Fort Chip. As Dr. O’Connor said, “[the Government of Canada has] not budged toward a health study that was promised ten years ago. Nothing has been done to get to the bottom of it and Warren becomes another statistic.”

“50 years old. His only risk is that he lived in Fort Chip.”

Support for residential school survivors and their families is available. Call the Indian Residential School Survivors Society at 1-800-721-0066 or 1-866-925-4419 for the 24-7 crisis line.

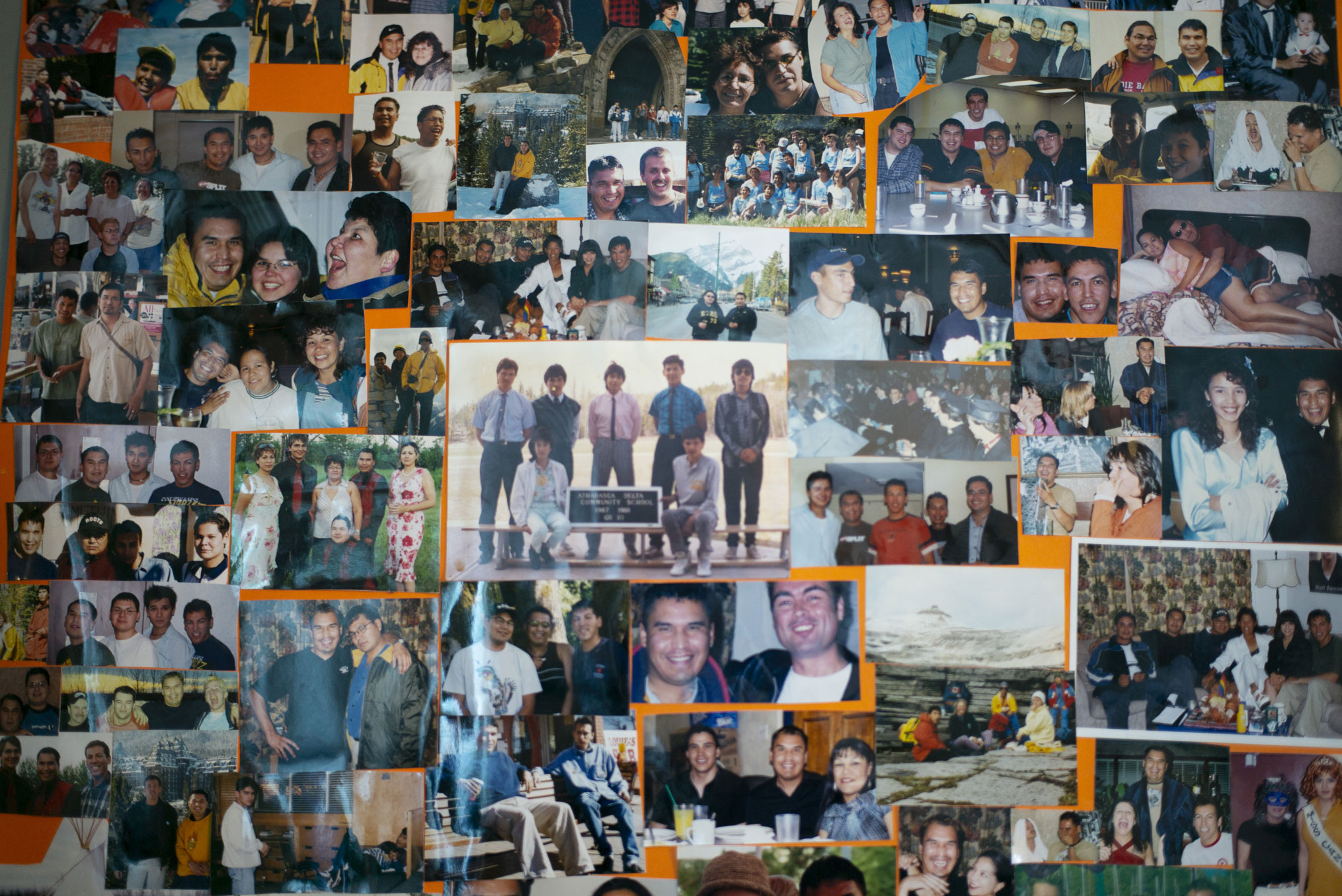

Updated on Oct. 31, 2022, at 11:18 a.m. MT: This story was updated to correct that Warren Simpson has two sisters, not one. It was updated again on Oct. 31, 2022 at 12:29 p.m. MT to clarify a caption below a photograph showing framed photos in the wall of the rectory on the campus of the shuttered Holy Angels residential school. A previous version of the caption incorrectly stated that the photo was taken at the school itself.