Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

Most Albertans are familiar with the idea that we’ve long been placing our eggs in the extractive-sector basket — a basket that keeps our province tethered to a relentless boom-and-bust cycle, and highly dependent on global energy prices.

All it takes is a decline in said prices for that reality to become all too clear.

But how dependent are we?

One is left wondering just how much the Alberta government relies on oil and gas royalties to pay for all of its programs — healthcare, education, roads and all the other basic services we have come to expect.

We do have other sources of revenue, right?

. . . Right?

We looked at some research from the University of Calgary to get a better idea. Turns out, economists are finding that, in Alberta, we’re in way over our heads when it comes to being dependent on fossil fuel royalties — those revenues we earn from the extraction of resources in our province.

So how can we make up for lost revenues in lean times? And how do we prepare for a future in which global demand for our products is set to decline?

As with any budget, Alberta has two big things to consider: revenues and expenses.

On the expense side of the ledger, the Alberta government spends money on goods and services — this part is pretty easy to understand (Alberta reportedly spends the most per capita on health care of all the provinces).

On the revenue side, Alberta earns money primarily through taxation — whether that’s an income tax, corporate tax, fuel tax, tobacco tax and so on. That comprises much of our revenue — about $21 billion of Alberta’s revenue came from taxes in 2017-2018.

The next biggest source of revenue are federal cash transfers. The federal government takes in its own revenue, and it distributes some of this to the province.

According to a 2015 paper from Ron Kneebone, a professor of economics at the University of Calgary, this non-royalty income is our most stable source of income as a province.

Kneebone, who’s also a director at the University of Calgary’s School of Public Policy, looked at how much we spend, compared to what we make in these ways.

Looking at data spanning more than four decades — from 1970 to 2014 — he found the province always spends more than it takes in, in non-royalty revenue.

Always.

Every. single. year.

Kneebone refers to this as the “budget gap” — the difference between the amount we spend and the relatively stable income sources we have to pay for it.

And the main way we’ve managed to make up for this gap are oil and gas royalties.

In 2015, soon-to-be-booted Minister of Finance Robin Campbell described royalty revenues as “a bonus that allowed us to pay the bills.”

So, for decades, that’s what we’ve done. It’s a bit like relying on your annual bonus to pay your bills.

“When households are faced with such a large and unpredictable source of income they generally choose to avoid relying on that income to fund key expenditures like the mortgage, food and the kids’ teeth,” Kneebone said in a 2013 paper.

“Instead what they do is form a best guess of what portion of that income they can safely rely upon. . . . The rest, because it is too uncertain to be relied upon to fund such basic expenditures, is usually saved.”

The fact Alberta regularly relies so heavily on royalty revenues has left it in a very unstable financial position.

It wasn’t always this way.

Dig back a little farther, and one finds that Alberta hasn’t really been earning royalties for all that long, relatively speaking.

When our province was created, we were a cash-strapped bunch, and heavily reliant on agriculture.

At the time, we didn’t even have control of our resources — the federal government held natural gas, oil and mineral rights until 1930.

Then, in 1947 — after drilling 133 wells and finding nothing — Imperial Oil turned their drilling attention to Leduc, Alta. They struck oil.

Resource revenue, in the form of royalties, started to flow, too. Royalties were initially levied at a flat rate, based on the amount produced.

It wasn’t until 1973 that the province tied royalty rates to the volatile price of oil.

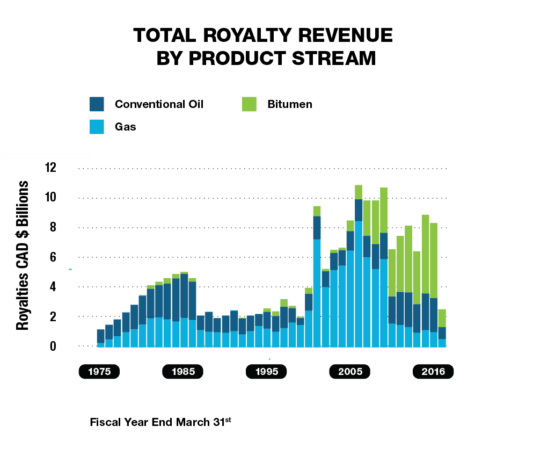

Prior to the last decade or so, the vast majority of our royalty revenue came from natural gas and conventional oil. Then came the bitumen — oilsands — boom, and things started to really take off.

Graph: Government of Alberta

No one in this province has talked about resource revenues without two syllables being uttered again and again.

Those two syllables represent an example of an alternative — how things might have been. Those two syllables come up every time we talk about our paltry Heritage Fund, and they come up when every time we talk about royalties.

Those two syllables are “Norway.” (Indeed, some people are so sick of hearing those two syllables they’ve coined the term Norwailing.)

Kneebone brings up Norway, too. While Alberta has always had a budget gap — spending more than we reliably earn — Norway’s budget gap is closer to zero, he argues in a 2013 paper about Alberta’s budget woes. Which means Norway pays for basic services with its stable income, and banks its resource revenue for future years.

And the kicker? When finances are approached this way, resource revenue can continue to earn interest for years to come, instead of being used up.

In this way — the Norway way — resource revenue can conceivably continue to provide earnings into perpetuity.

Kneebone’s paper encourages Albertans to look at resource revenue (royalties) not as a source of income, but as another type of savings account.

When we extract resources without saving the royalties, he argues, wealth is simply “being borrowed from future generations.”

Oil and gas in the ground, he explains, is a capital asset. It’s in finite supply. When we extract it, we can turn it into another form of asset — a financial asset — and earn interest.

But this is not what Alberta has done. According to Kneebone’s research, between 1983 and 2012, just eight per cent of resource revenues were saved.

For the five-year period before his paper was written, “not a penny” was saved.

Kneebone’s analysis found that rather than banking resource revenues, successive Alberta governments have taken boom years as a licence to provide bonuses to taxpayers, in the form of tax cuts or increased spending.

Kneebone coins it a “temptation for governments to gain favour with voters with cuts to tax rates and/or increases in services beyond what might otherwise be affordable.”

For every one dollar increase in resource revenues, Kneebone found that the government increased the budget gap by $0.48 the next year.

And, let’s not forget the logical extreme of the spend-it-while-we’ve-got-it attitude — our 2005 prosperity cheques

.

In 2000-2001, the province received 41 per cent of its revenue from income from resource extraction. In 2005-2006, 37 per cent. In 2013-2014, it was down to 21 per cent of total revenue.

And, most recently, in 2017-2018, that source of revenue was down to 11 per cent.

The decline puts the province in a tricky situation.

Replacing the revenue needed to close Alberta’s budget gap is difficult. There are two primary options: decrease spending or increase taxes (or increase royalty rates, but we know how that’s worked out, and economists question whether continuing to stake our future on oil is wise.)

The “government has tools,” to help it reduce its dependency on royalty revenues, Trevor Tombe, associate professor of economics at the University of Calgary, told The Narwhal.

Increasingly, economists are floating the idea of an Alberta sales tax — though politically the topic has remained virtually untouchable, despite being the only province in Canada without one.

“Switching to tax instruments that are broad and stable, like a sales tax, is something most other jurisdictions do,” Tombe said.

In a 2006 paper, economists Robert Mansell and Ron Schlenker of the University of Calgary highlighted just how big the province’s budget gap was, by pointing out the magnitude of a sales tax that would be needed to replace resource revenue.

In 2004, the pair argued, Alberta would have needed a provincial sales tax of around 16 per cent to replace its royalty revenue.

Albertans are, by and large, not receptive to the idea of a provincial sales tax, let alone a 16 per cent sales tax.

That may be in part because of what’s known as the “fiscal illusion” — the idea that government budgets obfuscate reality for many taxpayers.

As the theory goes, taxpayers have a difficult time fully understanding the true cost of government services when such a large portion of revenue comes from a source like a resource royalty.

We never see the money leave our wallets — like we do with an income or sales tax — so we don’t really appreciate how much running the province costs.

This is a reality that the Progressive Conservative party seemed to come face to face with in 2015.

“To put it in a household context, our weekly pay cheque has not been covering our day-to-day expenses,” Minister of Finance Robin Campbell said shortly before his Progressive Conservative Party was voted out of power.

“We have been lucky in recent years that resource revenues provided a bonus that allowed us to pay the bills.”

Kneebone’s paper summed it up: “It is a high-risk budgeting strategy that has been the bane of Albertans for decades.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...