‘Afraid of the water’? Life in a city that dumps billions of litres of raw sewage into lakes and rivers

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

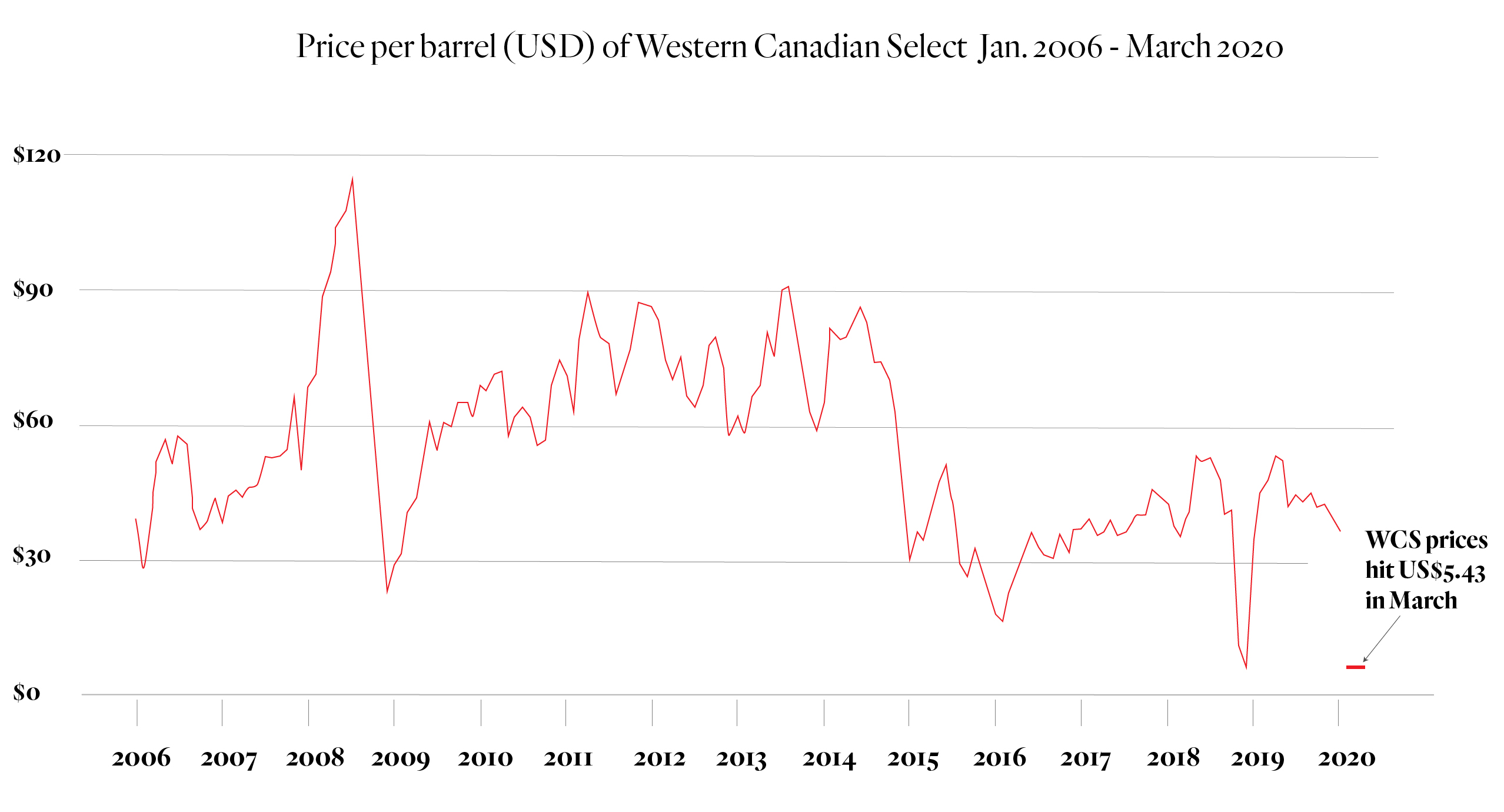

As world stock markets plunge in response to the novel coronavirus pandemic, Albertans have their eye on the price of oil.

Earlier this week, Western Canadian Select, the benchmark widely used to track the price for oil produced in Alberta’s oilsands, dropped to US$5.43 per barrel.

Five. Dollars. Per. Barrel.

That’s the lowest price ever seen for Western Canadian Select, according to historical data published by the Government of Alberta.

Prices have rebounded slightly since then, but as one journalist for The Globe and Mail tweeted, it’s “strange times” when market observers are celebrating a bump up to… US$11 per barrel.

This had led to recent reports that a massive federal bailout package for the industry could be in the making — to the tune of $15 billion for the oil and gas sector. On Friday, the Government of Alberta announced it would step in with $113 million in payments to the Alberta Energy Regulator, which is normally entirely funded by industry. The provincial government will pay levies owed to the regulator on the industry’s behalf for six months.

Warren Mabee, the director of the Queen’s Institute for Energy and Environmental Policy at Queen’s University in Ontario, points out that low oil prices are “not a new thing.”

“It’s not like last year oil prices were $100 a barrel and all the producers were laughing all the way to the bank,” he told The Narwhal.

Western Canadian Select previously dropped to close to US$16 per barrel in early 2016, briefly fell below to just below US$6 per barrel in 2018, and started 2020 at just over US$36 per barrel according to data from the Government of Alberta.

Western Canadian Select prices. Graph: The Narwhal. Source: Alberta government

Like what you’re reading? Sign up for The Narwhal’s weekly newsletter.

Oil prices, particularly in Alberta’s oilsands, have been suffering for a while, as the Alberta government had been forced to curtail production through at least December 2020 in an attempt to prevent further price drops, and many oilsands projects had already been cancelled or postponed. The onset of the COVID-19 pandemic has only made things worse for oil producers.

“All it takes is one big disruption that keeps us all inside,” Mabee said.

It’s times like these that highlight the fragility of Alberta’s oil and gas companies.

“We’re in a truly unprecedented panic mode. There’s been a market selloff that we haven’t seen since the 1920s,” Mabee said.

But as he pointed out, Albertan oil producers — already struggling with low prices and often high-cost products — are likely to suffer disproportionately.

The industry has also faced pressure as the world moves to decarbonize.

The Oil-Climate Index, which ranks North American crude oil by carbon pollution, consistently rates Canada’s Athabasca sweet synthetic crude oil at the top of its ranking of oil by emissions. The relatively high carbon footprint has put further strain on the oilsands as it seeks to compete with lower-carbon alternatives in the global market.

“Look at the returns you’ve gotten from the oilsands over the last five to six years,” economist Jeff Rubin told The Narwhal in 2018, long before COVID-19 emerged. “And consider how viable that resource will be if, in fact, the world does mitigate climate change.”

And as Mabee points out, even when the global pandemic recedes, long-term challenges for Albertan oil companies will continue as the province faces an increasingly competitive global market.

The COVID-19 pandemic is resulting in mass layoffs, closures and travel restrictions, which have huge implications on the global demand for oil.

Airlines have reduced flights by as much as 85 per cent, laying off thousands of workers.

The International Energy Agency, which had recently projected global oil demand would increase by 825,000 barrels a day in 2020 now instead predicts demand will decrease by 90,000 barrels a day compared to 2019.

“This kind of economic freeze and reduced oil demand feels completely novel,” Clark Williams-Derry, a Seattle-based energy finance analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, told The Narwhal. “I’ve never seen it. It is unprecedented.”

At the same time, oil markets are grappling with a huge supply-side shock.

Russia and Saudi Arabia, unable to reach an agreement on curtailment of production, recently flooded the market

with excess supply.

This shock has been a long time in the making, Mabee told The Narwhal, the result of years of disagreements about how to keep prices high as U.S. shale production (accessed through the controversial process of fracking) added unexpected supply to the markets.

As the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) worked to reduce supply in recent years in an attempt to keep prices high, the U.S., according to Williams-Derry, kept “going gangbusters,” with its production.

Ultimately, oil supply stayed high and prices stayed low. Recent actions by Russia and Saudi Arabia exacerbated that gap.

And that means even lower prices, at precisely the moment when demand is plummeting — particularly bad news for Alberta’s government.

Alberta was already on track to run a $6.8 billion deficit this year, despite dramatic cuts to government spending, with cuts affecting everything from healthcare to universities to parks.

“[West Texas Intermediate] oil prices are expected to remain flat,” the government predicted in its fiscal plan last month, noting it expected that price to be US$58 per barrel.

West Texas Intermediate (WTI) prices are currently less than half what the government forecasted.

Of course, the Alberta government had no way of predicting the global COVID-19 pandemic, which has rendered its oil price predictions next to useless.

As a result of those ill-fated projections, the province was relying on $3 billion in bitumen royalties, with expectations that those would only increase in the coming years.

Now the world is in a glut situation, according to Mabee. Storage tanks will fill up, and tankers will sit offshore, full of oil, waiting to find the market.

That drives prices down.

“We’re going to be in a situation where it’s going to be difficult for higher-cost producers to compete,” he told The Narwhal.

“One of the mistakes people make is painting the oilsands as one big monolithic thing,” Mabee said.

There are big players that have managed to keep costs down, but many Albertan oil operations face high break-even costs.

According to a 2019 economic review document published by the Government of Alberta, “the breakeven [WTI] price for a new stand‑alone mine is currently within the US$75‑85/ bbl range,” while in-situ production is lower, at around US$55 or US$60 per barrel — still way above WTI oil prices as of late.

Work is expected to slow down in the oilsands, due to a plunge in world oil prices. Photo: Alex MacLean

Oil from Alberta’s oilsands is almost always at a price disadvantage compared to its American counterparts, according to Williams-Derry.

Western Canadian Select, the oil price seen as a benchmark for oil from Alberta’s oilsands, suffers from what’s known as a “price differential,” when compared to the North American benchmark, West Texas Intermediate (WTI). That price differential is the result of two factors, according to Williams-Derry: location and quality.

Alberta’s bitumen has to travel further to reach most refineries that will process it, and much has been said about companies experiencing difficulty securing pipeline capacity.

“Alberta for years has faced the challenge of increasingly costly access to market,” Mabee told The Narwhal.

Oil from Alberta’s oilsands is also a different quality.

“We talk about oil as if it’s one thing. But it’s actually a range of things, a mixture of hydrocarbons,” says Williams-Derry. “Each barrel of oil is its own thing. Some of it is higher in sulphur or other impurities. Some of it is heavier.”

Alberta’s oil is heavier — similar to cold molasses, as Williams-Derry points out — and harder for many refineries to process. In short, it can be less desirable.

All of this leads to a lower benchmark oil price for Alberta’s oilsands. A benchmark is just that — a benchmark, meaning that some producers may be able to fetch a higher price, but also that some may be forced, out of desperation, to sell off barrels at even less.

As responses to the COVID-19 pandemic ramp up around the world, and governments warn measures to prevent the spread of the virus could last weeks or months, it’s hard to think beyond the immediate future.

But Mabee is confident “this crisis won’t last forever.”

And as governments grapple with how to respond to the shocks felt by oil and gas producers, he’s hopeful the long-term trends in the industry will be taken into account.

“The world is telling us through the faces of these trends that, you know, [global oil] demand has been changing, so let’s get in front of it,” he said.

“Crisis breeds opportunities… that’s something we know. So maybe this is a chance to start thinking about some of these things.”

Like what you’re reading? Sign up for The Narwhal’s weekly newsletter.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

10 billion litres of sewage are dumped into Winnipeg’s lakes and rivers each year. Some...

Court sides with Xatśūll First Nation, temporarily halting Mount Polley mine waste expansion

Break out the champagne: Emma’s storied life and leadership in journalism has earned her the...