86 per cent of a river gone: First Nation calls on BC Hydro to let more water through

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...

There are many iconic places in Canada’s North, but few give me a sense of awe like the barrenlands of the Northwest Territories. The remote, treeless landscape of rolling tundra and rocky outcrop extends in every direction as far as one can see.

Russell Drybones, a tall and lanky Dene guide, is, like the rest of us, looking for caribou.

“You can feel them, you know. The ground moves,” says Drybones, who earned the nickname Eagle Eyes for his ability to spot a caribou several kilometres away. “Who knows, maybe over that esker is 1,000 caribou ready to run and shake the land.”

But we don’t see 1,000 caribou. We don’t even see a handful. We’re not sure where they are and we’ve been looking for three days.

The population of the Bathurst caribou herd has plummeted in recent decades. In the 1990s, the herd was celebrated as a healthy migratory population in the hundreds of thousands. But today, there are roughly 10,000 individuals.

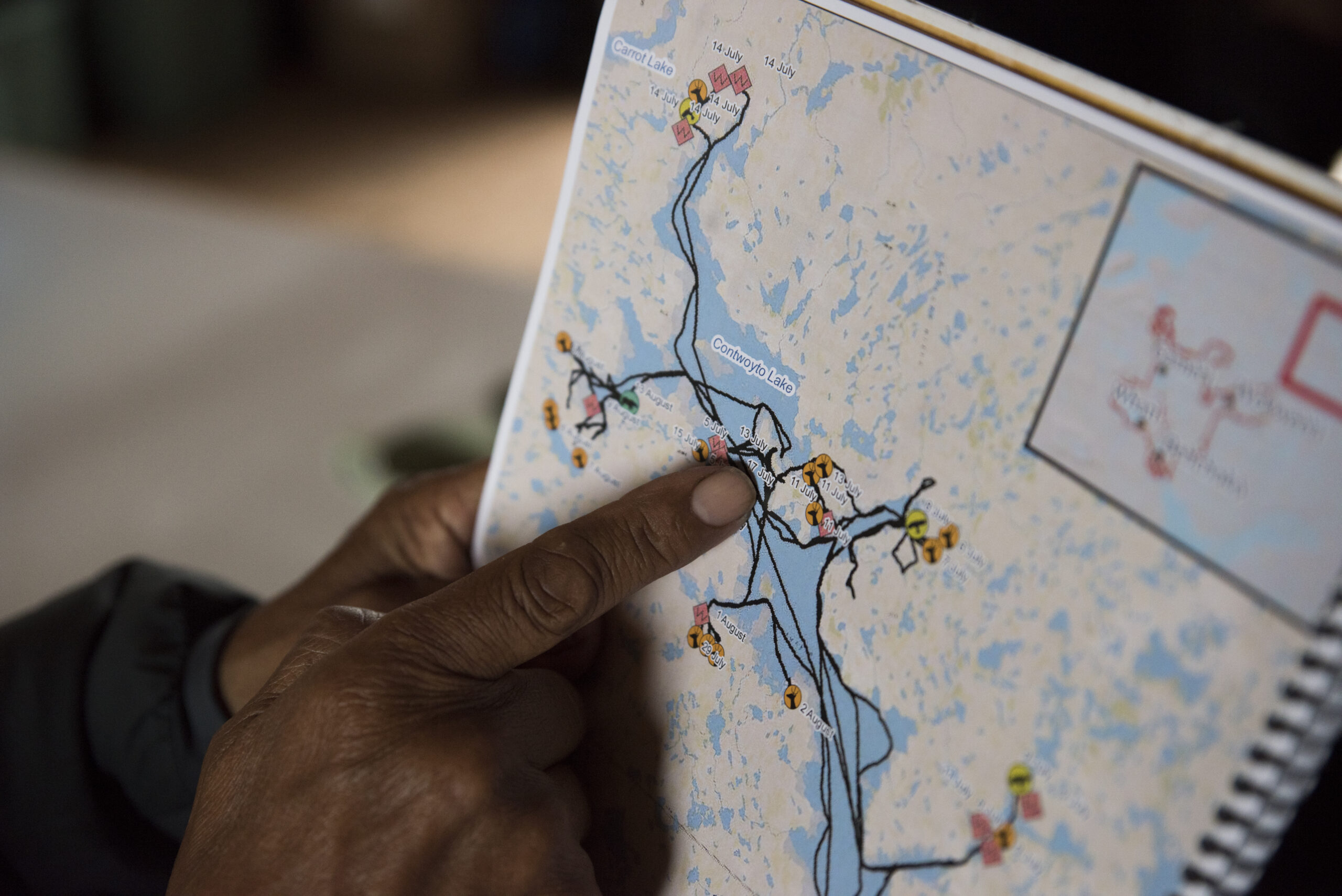

In 2015, the Tłı̨chǫ Dene communities of the Northwest Territories banned hunting with hopes it would help the herd rebound. But monitoring the health of a migratory herd that traverses thousands of kilometres of barren land a year is no small feat. It takes patience, persistence and intimacy with a remote herd very few people on the planet — even those in the Northwest Territories — will ever see.

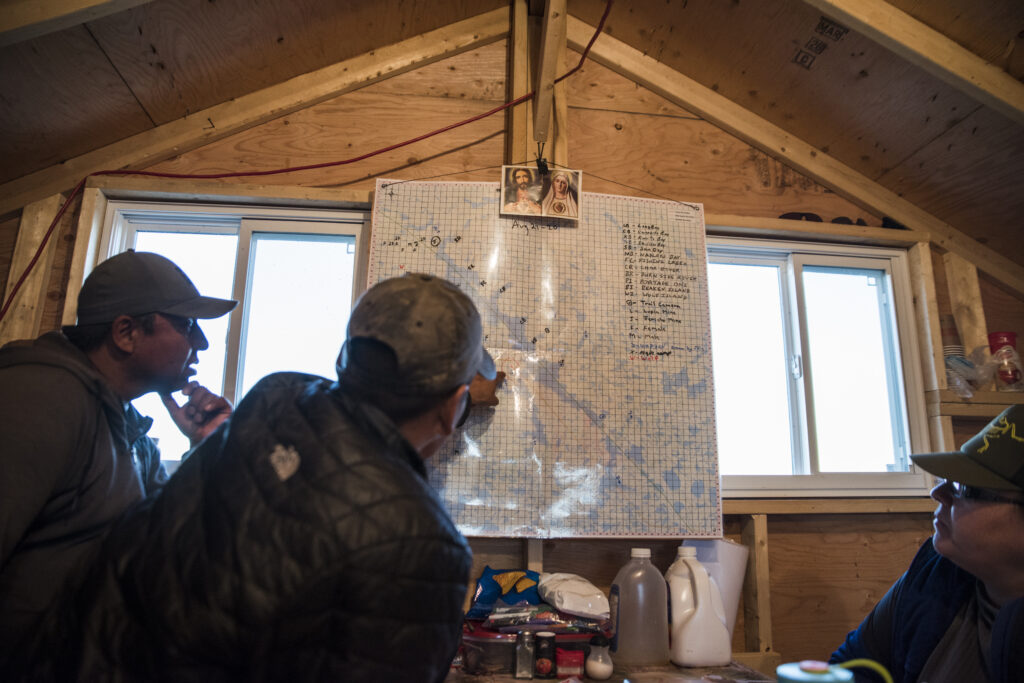

I spent 11 days at a small camp 500 kilometres north of Yellowknife documenting the work of the Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoède K’è: Boots on the Ground program, initiated by the Tłı̨chǫ Government to collect critical field knowledge of the herd and its habitat.

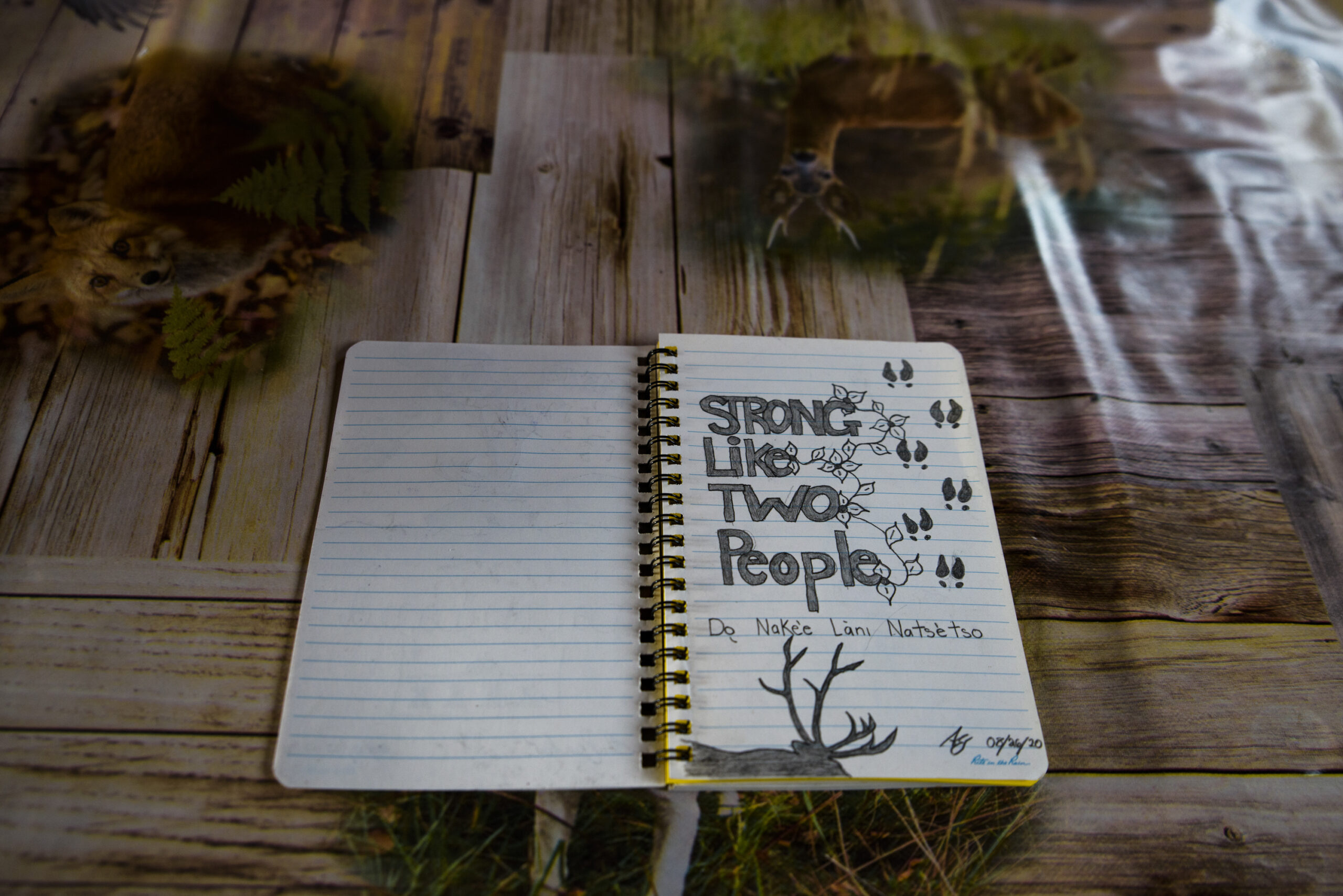

The monitoring program is unique in its design. Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoède K’è comes from the Tłı̨chǫ language and refers to the movement of the caribou herd throughout the year, from the calving grounds to the forest and back again. It encompasses the whole life cycle of the caribou.

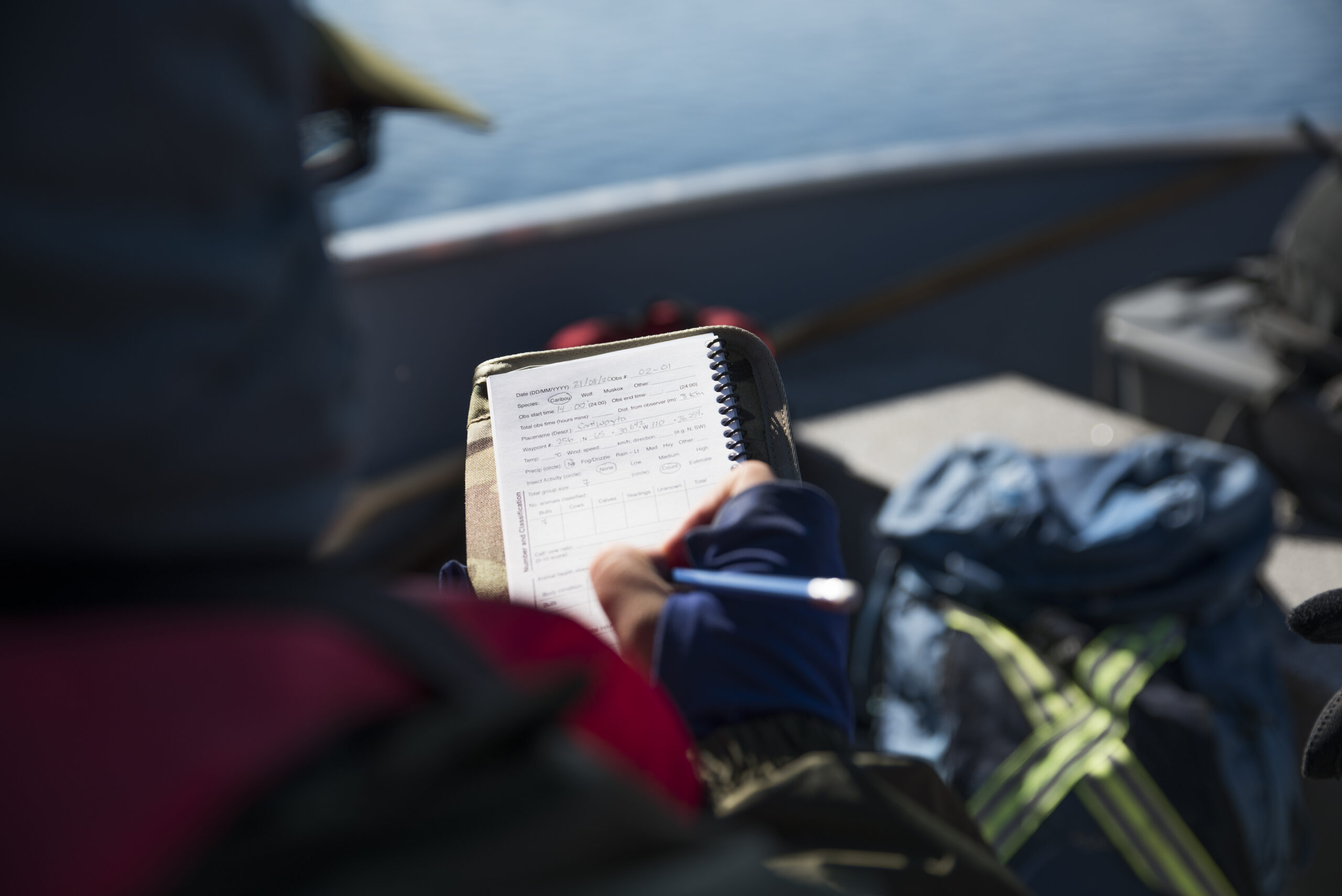

The program’s methodology follows a specific principle drawn from the very ways of life of traditional caribou harvesters: “do as hunters do.” Researchers attend to the herd and the landscape under a holistic concept of “we watch everything” that comes from Tłı̨chǫ Elders. They wait at na’oke, or water crossings, to track details about caribou and the environment, from predators to changes on the landscape from industrial activities.

The program is much more than a research project on caribou — it’s also a way for Tłı̨chǫ Dene to stay connected to their culture and identity.

The days were long, sometimes monotonous, with several hours of hiking and boating. It is a slow and patient way to study caribou and collect information. But it also allows for rich collaboration. The team — consisting of Tłı̨chǫ Dene Elders, officers from the territory’s Department of Environment and Natural Resources and researchers — made sure everyone was fed, safe from wildlife and rested.

That kind of collaborative effort is invaluable in a land that’s inhospitable, even potentially dangerous, despite being so full of beauty.

Reaching back into a rich reservoir of Traditional Knowledge, these individuals are charting a new way forward when it comes to researching and managing the creatures that share Indigenous lands.

The Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoède K’è: Boots on the Ground program is founded on the belief that local people who rely on the land are in the best position to determine the health of caribou.

Drummers sing while Louis Zoe feeds the fire with an offering of bread and tobacco, a way to ask The Creator for safe travel and offer thanks before the day begins.

Editor’s note: Pat Kane’s documentary photography of the Ekwǫ̀ Nàxoède K’è: Boots on the Ground program was supported by funding from the Tłı̨chǫ Government. As per The Narwhal’s editorial independence policy, the Tłı̨chǫ Government did not have any influence on the production of this work.