B.C. quietly allowed an oil and gas giant to sidestep rules for more than 4,300 pipelines

B.C.’s energy regulator has the power to grant exemptions — without notifying the public. Experts...

For decades, B.C. has been the wild west in terms of fossil management, with prized specimens damaged by development, exploited for commerce and winding up in private hands or in major institutions outside the province.

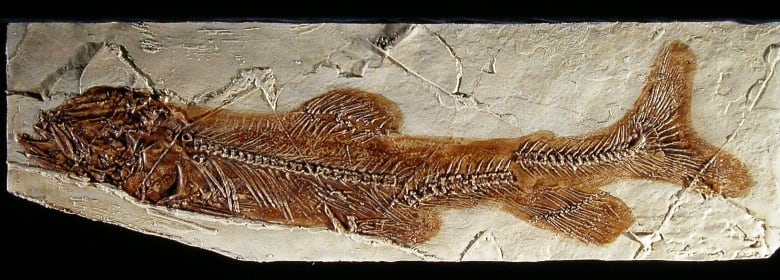

Gone are dinosaur tracks from the Peace River, fish fossils from Wapiti Lake and rare plant specimens from a chert site near Princeton. The biggest prize of all? A world-record 21-metre marine reptile — an ichthyosaur, Shonisaurus sikanniensis — plucked from the Sikanni Chief River and now on prominent display in the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alta.

Protection for B.C.’s fossils has been a long time coming, but, finally, a new provincial policy is being rolled out that not only puts collectors on notice, but industrial operators whose activities might destroy fossils on Crown land.

“The days of fossils just drifting off to other parts of Canada are gone,” asserts Richard Linzey, director of B.C.’s Heritage Branch, in Victoria. “We now value fossils, and they are managed alongside other values — cultural heritage, moose and crucial fish habitat, things like that. It’s very exciting.”

The largest marine reptile ever known to swim the oceans — the 21-metre ichthyosaur, Shonisaurus sikanniensis — was removed from British Columbia’s Sikanni Chief River starting in 2000 and taken to the Royal Tyrrell Museum in Drumheller, Alta. Photo: The Royal Tyrrell Museum

The new policy — officially, the Fossil Management Framework — applies across all natural resource ministries, and establishes the government’s ownership over fossils for their scientific, educational and heritage value.

The province is also seeking public input on designation of a provincial fossil. The short-list lacks the familiarity of the dogwood as B.C.’s official flower, our bird the Steller’s jay, or the Spirit Bear as our mammal, and includes obscure tongue-twister luminaries such as the single-celled Fusulinid foraminifera.

Fossils are defined under the Land Act as “preserved remains, traces or imprints of organisms from the geological past,” but do not include human remains or artifacts. Up until a few years ago fossils were lumped within minerals. “If you took out a mineral tenure, you had rights to the fossils,” Linzey says.

The government has now created an online map of areas where individuals and companies can expect to find fossils, including Vancouver Island, Haida Gwaii, Princeton-Merritt-Kamloops, southeastern and northeastern B.C., and the central Interior plateau. “If I am building my wind farm or housing estate, what are the chances of coming across fossils?” Linzey says.

The eosalmo-driftwoodensis is an ancient prefigure of the modern day salmon. The province of B.C. is currently asking members of the public to weigh in on which fossil should become a provincial symbol. Cast your vote before November 23, 2018. Photo: Province of B.C.

Under the new policy, companies should develop protocols and review the map before undertaking work. Any fossils discovered must be reported to the province’s Heritage Branch, which will determine the importance of the specimens, whether they must be removed or ways development might proceed to minimize risk of damage. If removal is required to a local museum or Royal BC Museum — the official steward of the province’s fossils — the company must pay the costs.

Going forward, if a company’s activities on Crown land require an environmental assessment within a known fossil area, then a fossil impact assessment must also be done. Any researchers seeking to remove fossils must obtain a permit.

Elisabeth Deom, in charge of paleontology for the Heritage Branch, confirms the policy is a huge advance from even a decade ago: “Let’s say there were no rules, per se, for fossil resources.”

The McAbee fossil beds, a 53-million-year-old forest east of Cache Creek, were commercially exploited for years until the site received provincial heritage designation in 2012. There are now calls for the beds to be declared a UNESCO World Heritage site.

During the first year of B.C.’s new fossil policy, the government will concentrate on education. Over the last five years, 49 investigations under the Heritage Conservation Act have led to zero fines and 13 cases in which stop-work directives were issued, none for fossils. Natural resource officers are tasked with compliance and enforcement under the new fossil policy.

While the province is also asking private individuals to report the discovery of fossils, Linzey notes “we can’t control everything” and that the goal is to “socialize people to the idea that fossils are important.” Individuals already possessing collections can keep them as custodians on behalf of the province.

Deom takes a glass-half-full approach to amateurs who’ve scooped up fossils over the decades for private collection or commercial sale. “They’ve collected, but they’ve also passed on the information on this sites so that local communities can take care of them. A lot of those collections have, in fact, been going to museums as a result. For me, it’s more happy stories than gloom-and-doom ones.”

Private collectors agree.

Wayne Sawchuk, one of the province’s leading amateur fossil hunters, based in the Peace River area, notes “there’s always been a tension between the private and scientific collectors.” In past years, Sawchuk collected fossils because they were at risk of being washed away, but that’s changed as Tumbler Ridge has emerged as a regional centre for the display of fossils, with the Dinosaur Discovery Gallery.

In 2002, Sawchuk discovered only the second dinosaur bones in B.C., in a canyon during an excursion with the Tumbler Ridge Museum Foundation. Sawchuk believes that private individuals will continue to play a role by rescuing fossils valuable in their own right, but of no interest to institutions.

“Anything out in the open deteriorates very quickly,” he warns. “Within five to 10 years a lot of these things will be destroyed.”

Eva Koppelhus, curator for paleobotany and palynology collections at the University of Alberta in Edmonton, with a collection of plant fossils obtained from a chert site near Princeton, B.C. Photo: Philip Currie

The other key component of the new policy is to create a database of B.C. fossils currently stored with major institutions across the country — not just Royal Tyrrell Museum, but University of Alberta in Edmonton, Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto and Canadian Museum of Nature in Ottawa.

Easier said than done.

Eva Koppelhus, curator of paleobotany and palynology at the University of Alberta, reckons she has about 100,000 B.C. specimens in her collection, much of those from the Princeton fossil site, but the vast majority hasn’t been catalogued onto a computer. She told the B.C. government it should consider hiring some university students to help digitalize the collection, but hasn’t heard back.

Royal Tyrell has a better handle on it, estimating 11,800 B.C. fossils in its collection, much of those from the famous Burgess Shale fossil deposit in Yoho National Park in the Rocky Mountains — federal lands not subject to the province’s new fossil policy. The museum also has dinosaur tracks obtained during construction of the WAC Bennett dam, in the 1960s. “I’m not aware of any permits that were used to collect this stuff,” says Brandon Strilisky, head of collections.

The Burgess Shale is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, located high in the Rocky Mountains. According to The Burgess Shale Geological Foundation, the area “is a record of one of the earliest marine ecosystems giving a tantalizing glimpse of life as it was over 500 million years ago.” Photo: Chloe Johnson / The Burgess Shale Geological Foundation

The Royal BC Museum states that “planned development of the Site C dam by BC Hydro will undoubtedly generate many specimens from multiple sites in an area well known to be rich in fossils.”

BC Hydro says it already has in place a paleontological inventory and impact assessment to record and evaluate paleontological sites, and has collected more than 1,000 specimens to date. (An inspection report from the B.C. Environmental Assessment office last year found that BC Hydro had violated its environmental assessment certificate for Site C, failing to develop acceptable mitigation measures for an aboriginal sweat lodge and suspected burial site.)

Strilisky supports B.C.’s new policy, saying “late is better than never,” and noting Ontario and Quebec also lack fossil protection.

“These are animals that are never going to walk the Earth again. This is your last-ditch effort to protect them.”

And while B.C. is not demanding the return of any fossils — at least, not yet — Strilisky notes that Alberta is represented in the dinosaur collections of Smithsonian Institution, in Washington, D.C., and American Museum of Natural History, in New York City. “We’ve never considered asking to have those repatriated,” he says. “It’s free marketing for the province, we have a place on the world stage when it comes to the understanding of the history of animals.”

One of the biggest challenges ahead for B.C. is to find the resources to house a potential onslaught of new fossils. The Royal BC Museum already houses about 90,000 fossils, and expects the need for storage space to almost triple during the next three to five years, including from donations from private collectors. So far, no decision has been made on how that’s going to be funded.

“I anticipate the collection to grow rapidly,” confirms Victoria Arbour, the new curator of paleontology at Royal BC Museum. Some specimens, such as dinosaur bones, can fall victim to pyrite disease and decay if stored in humid conditions. “We want to hold ourselves to a high level of care.”

For fossils measured in the millions of years, it seems the wait for a permanent home in B.C will continue a little longer.

Editor’s note: The government of B.C. wants you to vote on your favourite fossil to be designated alongside the spirit bear and dogwood tree as provincial symbols. Cast your vote by Friday, November 23, 2018.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On March 17, federal Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre...

Continue reading

B.C.’s energy regulator has the power to grant exemptions — without notifying the public. Experts...

The current trade war with the U.S. means Canada must confront whether its domestic food...

Residents and nearby First Nations wanted a new environmental impact assessment of the contentious project....