Rocky Mountain coal mine in Alberta takes next step to expansion

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

B.C. is considering a proposal for a new coal mine, planned in the heart of critical habitat for the endangered Quintette caribou herd in the province’s Peace region.

The population of the Quintette herd, which roams the mountains near Tumbler Ridge where the Sukunka coal mine would be built, dropped from an estimated 173 to 74 animals between 2008 and 2018.

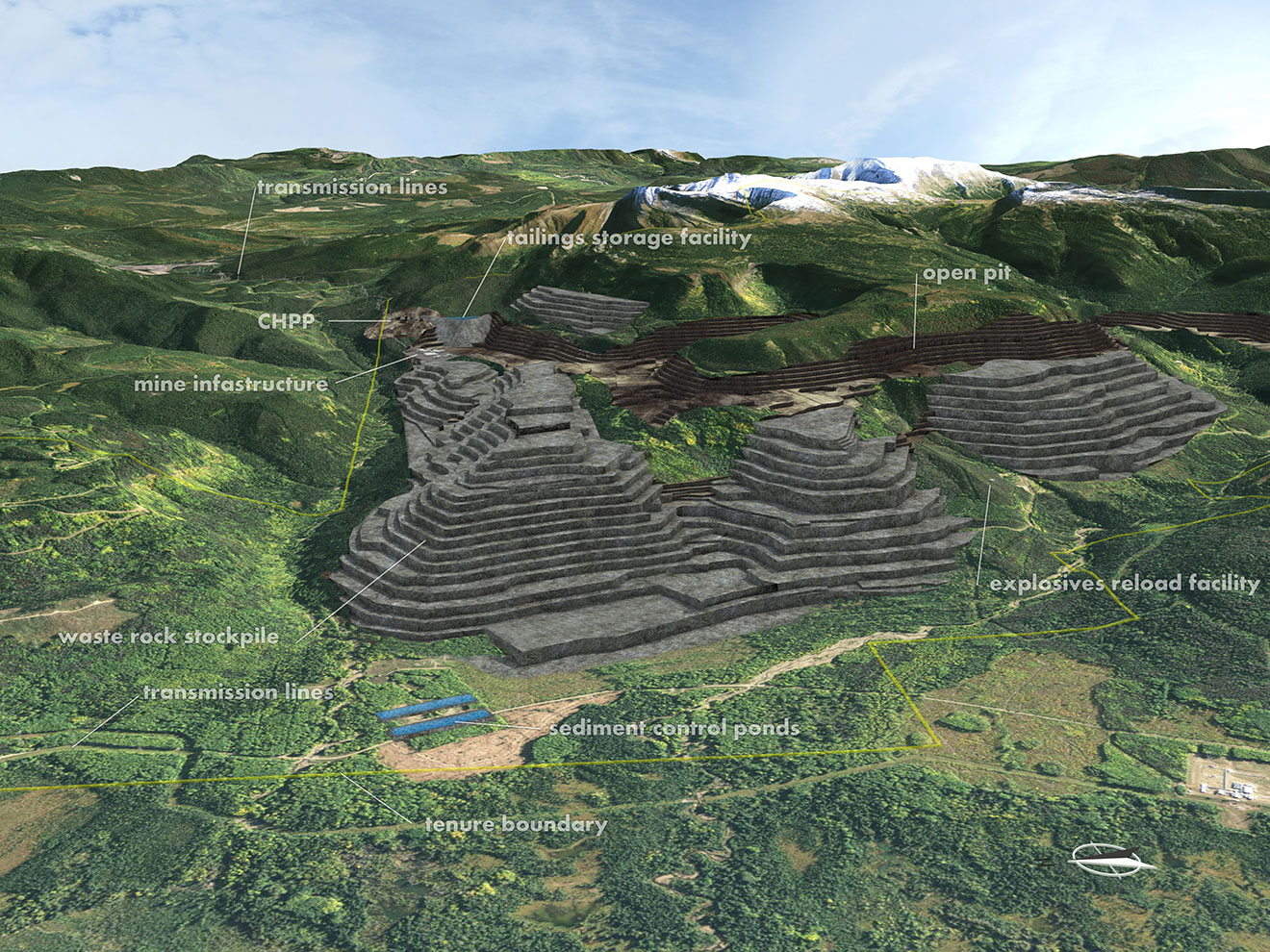

In a map submitted to the province by the project’s proponent Glencore, coloured dots indicate how the Quintette herd utilizes the mountain range year round, roaming areas that will be impacted by multiple open pits, roads, a tailings pond and other mining facilities — should the project go ahead.

Chief Roland Willson of West Moberly First Nations said it’s frustrating to see a new mine proposed in a region of B.C. where extraordinary measures are being taken to bring caribou back from the brink, including the nation’s costly maternity penning project for the endangered Klinse-Za herd that includes 24-hour armed security for pregnant cows and calves.

The open pits of Glencore’s Sukunka coal mine project shown in relation to caribou summer and wintering grounds in northeast B.C. The coloured dots and triangles show the location of caribou based on radio collar telemetry data. Map: Stantec

“For us it’s clear cut that the coal mine should not be going forward because you can’t mitigate the effects on the caribou in any way,” Willson says. “That project should be dead.”

But Willson says he has little confidence that the government will stand in the project’s way.

“When you look at the track record of how many projects have been approved that should not have been approved, B.C. does not have a good track record,” he says. “And Canada does not have a good track record.”

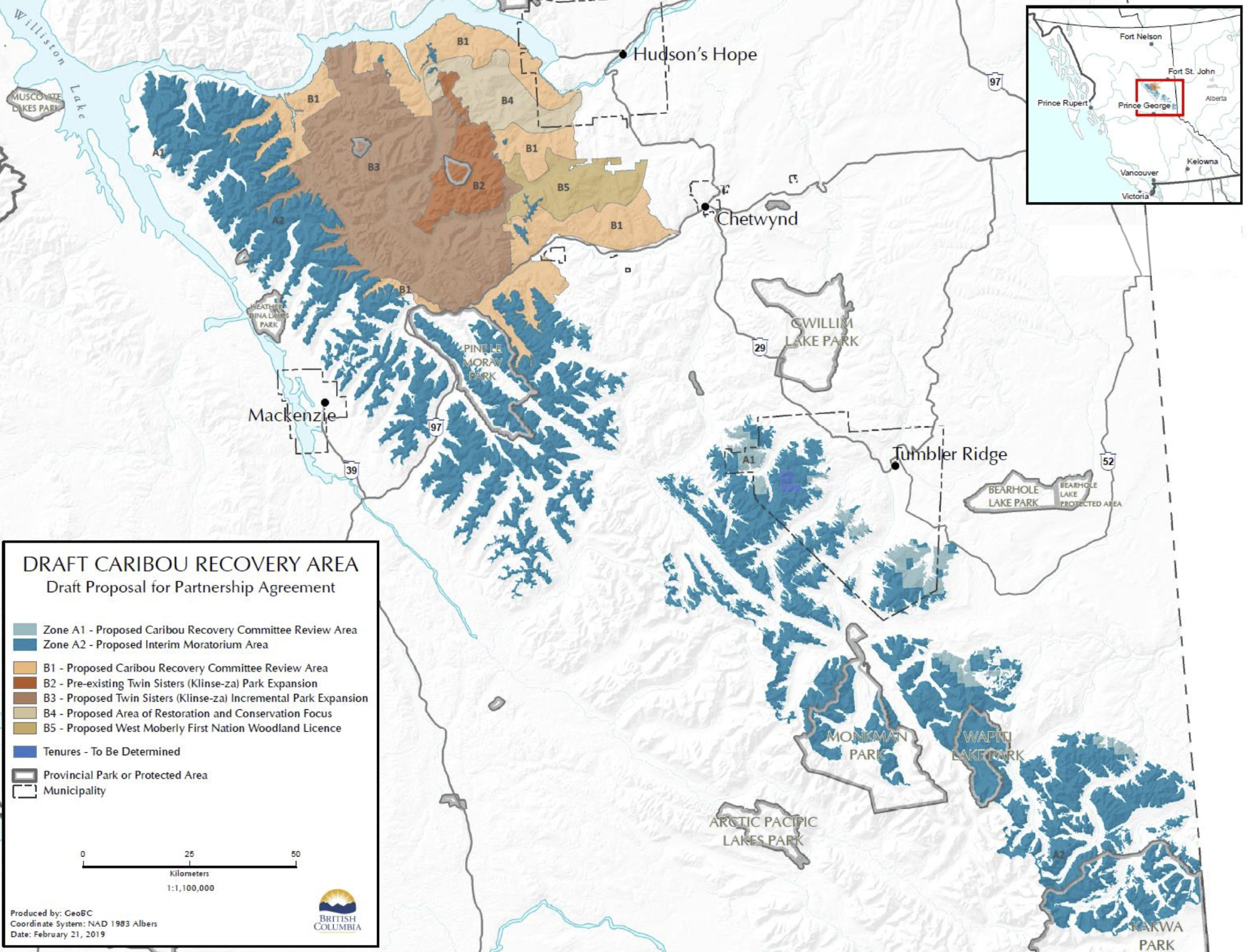

The mine is located within the boundary of areas newly protected under a 30-year agreement between the provincial and federal governments and the West Moberly and Saulteau First Nations.

The agreement, announced in February, placed interim protections on 550,000 hectares in the mountainous area west of Hudson’s Hope and includes plans for a new 206,000-hectare provincial park.

The new protected areas were designed to bring six struggling caribou herds, including the Quintette, back from the brink in the Peace region, the epicentre of much of B.C.’s oil and gas and fracking development, forestry, hydro operations and mining.

At an announcement for the new agreement that would see members of the West Moberly and Saulteau act as land guardians to protect species, federal environment minister Jonathan Wilkinson said “we need to do things differently” to ensure development is sustainable.

“This agreement is a model for caribou recovery efforts across this country,” he said at the time.

Yet certain zones within the protected areas include special permissions for mining and allow for ongoing development in endangered caribou habitat.

“You can see pretty clearly how some of the moratorium areas were essentially drawn around projects like Sukunka,” says Tim Burkhart, a program manager at the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative.

A map showing protected areas in B.C.’s Peace region, announced in a February 2020 new partnership agreement between B.C. and the West Moberly and Saulteau First Nations. The area marked Zone A1 near Tumbler Ridge is where the proposed Sukunka coal mine is located. Map: Province of B.C.

Willson says the fact that the mine is being considered is a red flag that makes him question the validity of the caribou protections that were put in place in the new agreement.

“If it’s going to hold water, that should be the test right there,” he says.

According to Glencore, the Sukunka mine could initially produce as much as three million tonnes of steelmaking coal each year — with a potential to grow that capacity to six million tonnes.

A company project description suggests the loss of habitat for caribou could result in fewer calves born, fewer adults surviving and better hunting for the wolves that prey on the.

Wildlife ecologists that prepared a short submission on the Sukunka mine for the B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy said the drastically diminished Quintette herd is currently being supported through a province-sponsored wolf cull and that the loss of the herd’s habitat will hinder recovery efforts.

In an additional submission to the province, one of the ecologists, Dale Seip, noted the mine “will directly destroy 24 hectares of core high elevation winter range and 256 hectares of core high elevation summer range.”

“Any additional destruction of core caribou habitat is inconsistent with efforts to recover these endangered caribou herds, and will increase the risk of the animals being extirpated.”

The ecologists found that other mine expansions in the region forced caribou to abandon their high elevation ranges and while in lower elevation ranges they became easier prey for wolves.

They also found the total disturbed area of the project, including a buffer zone around the mine itself, could amount to nearly 20,000 hectares of core caribou habitat. Their report concluded that that scenario could result in caribou abandoning more than a quarter of their winter area.

“The current habitat condition for Quintette caribou is unable to support a self-sustaining caribou herd, necessitating a wolf control program to maintain the caribou herd,” the ecologists wrote in their submission.

“An objective to recover the herd to a self-sustaining condition would require the habitat condition to improve over time until the wolf control program is no longer needed. Any additional destruction of core habitat, including this mine proposal, is inconsistent with that objective.”

The environmental assessment process is designed to weigh the benefits of a proposed project against its anticipated environmental and social harms.

Yet projects that enter into the environmental review process are rarely rejected, even despite notable impacts on caribou.

A study released in March reviewed 65 environmental assessments for projects in caribou habitat that had potential adverse impacts on the species.

All but one of the 65 projects were approved.

Environmental assessments are often used as a means to justify projects in caribou habitat, explains study co-author and UBC geography professor Jessica Dempsey.

“We know the state has multiple, conflicting obligations,” she says, and yet, environmental assessments are providing governments with a way to say,“ ‘We can have development, but we’ll just mitigate for the impacts.’ ”

Whether those impacts are actually being mitigated, however, is a question the government has been accused of ignoring.

A 2011 report from the B.C. auditor general found the Environmental Assessment Office “is not evaluating the effectiveness of environmental assessment mitigation measures.”

The study found that having effective mitigation measures in place was not even required to pass through the environmental assessment process and have a project approved.

In eight of the 65 assessments, the process determined that the measures were “inadequate, with significant adverse effects for caribou,” according to the paper, “but these projects proceeded anyway, on the promise that their positive [economic] effects would outweigh the costs.”

In the Sukunka project, one of the mine’s pits, which overlaps with caribou summer range, could feasibly be dug underground to minimize disturbance, but a technical study by Stantec found that would add cost, and recommended another open pit instead.

A rendering of the proposed Sukunka coal mine. Photo: Glencore

Dempsey’s study ultimately found that environmental assessments, which are viewed as a tool for sorting harmful projects from benign ones and adding accountability along the way, often acted instead as a rubber stamp.

The authors of the study conclude that environmental assessment “is meant to be a site where the state balances its obligations to promote economic development and to protect people and ecosystems.”

These assessments are meant to achieve a “win-win” for development and protection and yet, the study concludes, when it comes to caribou the result is “win-almost always lose.”

In 2018 the federal government estimated there are 3,764 animals left in all of B.C.’s southern mountain caribou herds. That’s 2,000 fewer than it counted just four years earlier.

Woodland caribou depend on large, undisturbed tracts of intact land to survive. They migrate from mountain top to valley bottom and spread out across vast landscapes to escape predators. That makes them especially sensitive to habitat loss and fragmentation — the kind of fragmentation that has accumulated on the landscapes over the course of the last century.

There are less than 300 caribou left to represent all six Peace region caribou herds — all of which are considered at immediate risk of local extinction.

One of the Peace’s caribou herds was officially declared locally extinct after its last member fell into a coal exploration pit in 2011 and died.

“What’s happening to the caribou here is not something natural,” Willson says.

The fast drop in population has been pinned squarely on the encroachment of human activity in caribou habitat, including logging, oil and gas, and mining development (and their associated road building) each of which are worth billions of dollars in gross domestic product in B.C.— and tens of thousands of jobs.

West Moberly Chief Roland Willson. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

From Willson’s perspective, the caribou decline in the Peace region started with the construction of the WAC Bennett Dam along the Peace River. When it was completed in 1967, it flooded more than 1,700 square kilometres of the upper Peace River to create the Williston Reservoir, the third largest artificial lake in North America. That cut off the caribou migration, splintering herds and setting populations rolling off a cliff.

The B.C. government apologized in 2016 for the damage the dam caused to First Nations communities. That hasn’t stopped it from proceeding with the Site C dam downstream.

The failure to not only protect the caribou but actually return the herds to sustainable levels, Willson says, is in itself a violation of Treaty Rights.

“We’re in a treaty infringement right now because we can’t hunt caribou,” he says.

Willson has continued to see all manner of resource development criss-cross the territory, chopping up caribou habitat into ever-smaller pieces while the government promises to protect the caribou his people once depended on.

“B.C. doesn’t make money saving caribou,” he says. “They’re drunk on the natural resources of British Columbia.”

The benefits of economic development are all too often considered above the value of protected, undeveloped habitat.

A study published in May in the journal Conservation Science and Practice found that after 900 square kilometres of critical caribou habitat was formally mapped and identified on provincial lands in B.C., the government still allowed that land to be logged.

“That identification of critical habitat in 2014 didn’t really change anything,” lead author Eric Palm, a wildlife biology PhD candidate at the University of Montana, told The Narwhal. “The amount of critical habitat logged actually increased.”

The forestry sector in B.C. alone employs nearly 20,000 people. “There are people’s jobs at stake,” Palm says. “That could be an argument that those job losses are more important than protecting caribou habitat.”

The B.C. Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development said in an emailed statement to The Narwhal, “Forest managers in B.C. recognize that forestry needs to be a part of the solution and past approaches are currently being reflected upon.”

Palm’s study found that, because of continued declines in southern mountain caribou numbers, ‘alternative mechanisms’ were needed to protect the species and their habitat. The authors proposed the use of a “cumulative effects framework” as a compliment to existing environmental assessment processes in order to assess and manage “effects that accumulate from multiple sources across the landscape on different ‘values’ such as old-growth forests.”

Considering the overlapping effects could improve the environmental assessment process that is currently failing, says biologist Aerin Jacob who was a co-author of the report and works with the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative.

“The very tool that is supposed to help guide us to make good decisions is over and over and over again allowing caribou to fall through the cracks,” she says.

The concept of cumulative effects of industrial development recently made legal waves in a decision by Alberta appeals court justices to refuse a proposed oilsands project. The ruling, which has implications for the West Moberly First Nations and other Treaty 8 nations, found governments must consider the impacts multiple natural resource projects will have on Aboriginal Rights.

Looking into the future, Willson sees hope in the First Nations’ maternity penning program, which he says the provincial government initially refused to permit. The project has increased the population of the Klinse-Za caribou herd from 16 animals to well over 100 in just six years. Willson said one day hopes the herd will be healthy enough to support traditional harvesting.

“They were a staple for food for the community,” he says, relating Elders’ stories of seeing caribou herds so large and widespread they were “as thick as bugs” across the landscape.

“You could always go and find a caribou in the mountains if you needed to.”

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. A $335 million funding commitment to fund...

Continue reading

In Alberta, a massive open-pit coal mine near Jasper National Park is hoping to expand...

A trade war could help remake B.C.’s food system, but will family farmers be left...

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...