Hope for a huge, ancient and imperilled fish

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

In an historic deal, two First Nations from B.C.’s Peace region and the federal and provincial governments today signed a partnership agreement that aims to pull six caribou herds back from the brink of local extinction.

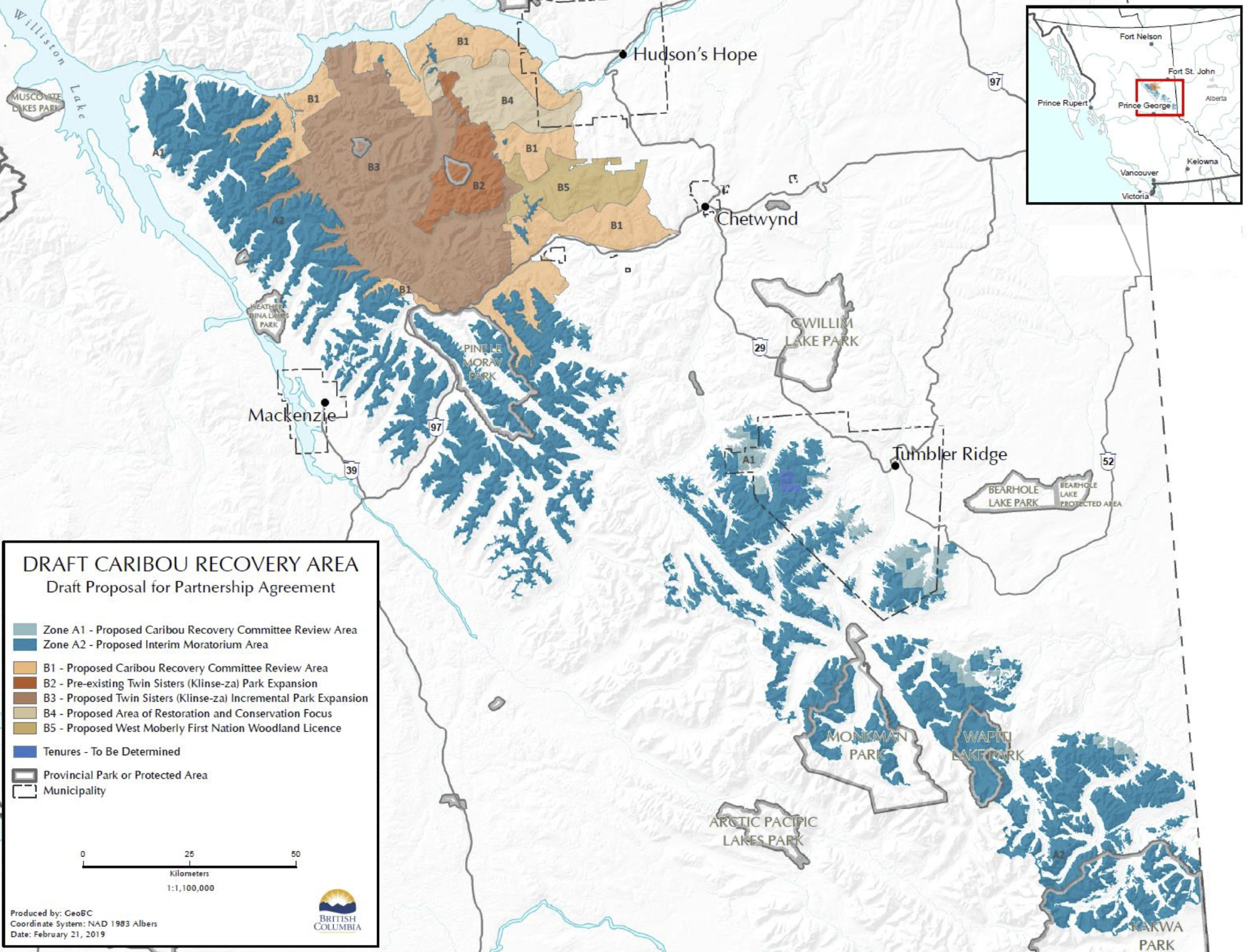

The agreement includes the eventual creation of a new 206,000-hectare provincial park — two and a half times the size of Manning Park — and places interim protections on another 550,000 hectares in the mountainous area east of Mackenzie and west of Hudson’s Hope and Chetwynd.

It also rolls out an Indigenous Guardians program to be led by West Moberly First Nations and Saulteau First Nations, who five years ago initiated costly and elaborate efforts to save the imperilled Klinse-za southern mountain caribou herd through a maternal penning project.

“It’s a big deal,” West Moberly First Nations chief Roland Willson told The Narwhal. “It’s exciting that we’re getting this done.”

Conservation groups lauded the agreement, calling it a blueprint for southern mountain caribou conservation in other areas of B.C. where waning herds are also at great risk of local extinction.

“We are over the moon,” said Tim Burkhart, manager of the Peace region for the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative. “This is the first expansion of the protected areas network in the Peace in almost 20 years.”

Only 4.2 per cent of the biodiverse Peace landscape is currently in a protected area or park, far less than the provincial average of 15 per cent.

The new park — an expansion of the existing 2,700-hectare Klin-se-za Provincial Park — will bump up Peace area protections to 6.7 per cent of the landscape, which includes increasingly rare old-growth boreal forest and a tapestry of rivers, lakes and wetlands.

Unlike in most of the rest of the Peace region, which is ground zero for resource development in B.C. — with industrial forestry, extensive fracking operations, conventional oil and gas development and mining — forestry is the only active industry in areas slated for protection, although there are also coal tenures.

West Moberly chief Roland Willson at a caribou maternity pen project in the Peace. Photo: Jayce Hawkins / The Narwhal

Burkhart said the areas covered by the agreement will provide robust protection for 36 provincially endangered (red-listed) and threatened (blue-listed) species in addition to caribou.

Those species include fisher, grizzly bear, white sturgeon and bull trout, birds such as the Canada warbler and olive-sided flycatcher, and plants like the small white water lily and birdfoot buttercup.

Willson said he is relieved the partnership agreement has finally been signed, after a backlash of racism and misinformation last year threatened to derail it.

“It’s by no means going to cure everything but it’s a step in the right direction,” Willson said. “Our members and Saulteau members deserve a round of applause … We were able to come together and work through this.”

Federal Environment Minister Jonathan Wilkinson commended the nations for taking a leadership role in protecting caribou, which he called an “iconic” and “umbrella” species.

“If the caribou in the forest are in trouble many other species are as well,” Wilkinson said during a Vancouver press conference at which the partnership agreement was signed.

The minister pointed to a 2019 United Nations report which warns nature is declining at rates unprecedented in human history, with one million plants and animals globally threatened with extinctions that will have grave impacts on people around the world.

Wilkinson said “we need to do things differently” and ensure that environmental sustainability underpins development. He cited the partnership agreement as an example of what can be achieved through collaborative partnerships.

“This agreement is a model for caribou recovery efforts across this country.”

A map showing new protected areas in B.C.’s Peace region, announced in a new partnership agreement between B.C. and the West Moberly and Saultau First Nations. Map: Province of B.C.

Caribou, which are engraved on the Canadian quarter, are in sharp decline across Canada, with habitat destruction the principle reason for their demise.

Only a few decades ago, First Nations elders described caribou in the Peace region as “like bugs on the landscape” because they were so plentiful.

Caribou numbers dropped sharply following construction of the W.A.C. Bennett dam in the late 1960s. The dam cut off a migration route and precipitated other industrial development that fractured caribou habitat, facilitating predation of herds by wolves.

Today, all six caribou herds in the Peace region are at risk of local extinction, with a total of only 230 animals remaining.

At last count in 2018, the Quintette herd had 74 animals, down from 200 in the early 2000s. The Narraway herd had only 26 animals left, a decrease from 150 in the early 2000s.

A seventh Peace caribou population, the Burnt Pine herd, became extirpated in 2011 after its last surviving member fell into a coal exploration pit.

In 2013, with only 16 animals left in the Klinse-za herd — named after the Klinse-za or Twin Sisters mountains, which are sacred to First Nations — the West Moberly and Saulteau nations decided to take matters into their own hands following inaction from the provincial and federal governments.

They launched a maternal penning project that, in tandem with habitat restoration and wolf culls, has seen the number of animals in the herd rise to more than 80.

Willson, who held up a caribou antler at the press conference, said he is hopeful the herd will top 100 animals this year and caribou populations will eventually recover enough for the Dunne-za people in northeastern B.C. to once again hunt the animal on which their ancestors depended.

“We’ve got signatures on paper right now but we have to put action to those words,” Willson said. “The work starts now. We have to roll up our sleeves and get going on this.”

The 30-year partnership agreement promises long-term support for caribou recovery efforts, including multi-year funding for maternal penning, habitat restoration and an Indigenous Guardians program.

It also includes federal funding to address impacts on tenure holders in the new protected areas, said Doug Donaldson, B.C.’s Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development.

“Today is a joyous day, an historic day,” said Donaldson, who joined Wilkinson in commending the two First Nations for their leadership. “It shows that three governments working together in respectful dialogue can achieve tremendous results.”

Charlotte Dawe, conservation and policy campaigner for Wilderness Committee, said the agreement is the “first plan of its kind” in B.C. that puts endangered caribou needs as the top priority.

Wilderness Committee has documented the number of new cutting permits the provincial government has issued in endangered caribou critical habitat, calling for an immediate halt to clear-cutting in those areas.

“We must hold this plan as the gold-standard going forward on the caribou file and follow the leadership of First Nations on protecting wildlife and wilderness areas,” Dawe said in a statement.

She said B.C. should look to other interested First Nations for partnership on agreements to protect wildlife under the federal Species at Risk Act (SARA), which enables Canada to enter into agreements with First Nations and provincial governments to benefit species at risk.

“This is a rare example of SARA being used and implemented in the way it was meant to be — to save species at risk,” Dawe said.

The signing of the agreement marks a turning point in an often bumpy road to protection for the central population of southern mountain caribou.

When the draft partnership agreement was announced last April, local communities said they had not been adequately consulted and hundreds of people flocked to public meetings that were often acrimonious.

B.C. Premier John Horgan subsequently appointed Dawson Creek city councilor Blair Lekstrom, a former south Peace MLA and energy ministry for the BC Liberals, as a community liaison. The premier extended deadlines for community consultation, expressing hope that Lekstrom’s appointment would help to reduce the rancour and find common ground to protect caribou.

Lekstrom, whose report to the government was criticized by scientists for showing “extreme bias,” resigned last month, saying the government had not implemented the vast majority of its recommendations or altered the draft agreement.

B.C. government delays endangered caribou plan as herds dwindle

Had B.C. not taken action to protect endangered caribou herds, the federal government was poised to step in and issue an emergency protection order under the federal Species at Risk Act.

That would have allowed Ottawa to make decisions that are normally within the jurisdiction of the B.C. government, such as whether or not to grant logging permits and close backcountry access.

Horgan, in a January letter to the Peace River Regional District, noted that more than two years had elapsed since the federal government ordered the creation of a caribou recovery plan.

“In a recent meeting with the Honourable Jonathan Wilkinson, federal Minister of Environment and Climate Change, I heard directly from the minister about the urgency and importance he places on this file,” Horgan wrote to the district.

Ken Cameron, chief of Saulteau First Nations, said the past few weeks — which have seen protests and blockades across the country in support of Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs who oppose construction of the Coastal GasLink pipeline through their traditional territory — have left people wondering if if there is anything real about the word “reconciliation.”

“Today is an example that we can achieve reconciliation,” Cameron said at the press conference, thanking Horgan for his work on the partnership agreement.

“We can make this dream come true and save a species from extinction.”

The federal and provincial governments also signed a second, far less detailed caribou agreement that covers the remainder of B.C.’s imperilled southern mountain caribou herds. That agreement does include any habitat protections or proposed restrictions on industrial development.

Instead, the bilateral agreement focuses on measures such as continued wolf and moose kills and keeps the door ajar for new B.C. government logging approvals in critical caribou habitat. It makes a commitment to developing plans “to reduce habitat disturbance” for 21 caribou herds but without any fixed timelines.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. Angello Johnson’s shoulders burn, and his arms...

Continue reading

First Nations are leading efforts to make sure lake sturgeon can find a home in...

We’re excited to share that an investigation by The Narwhal is a finalist for the...

A new documentary, Nechako: It Will Be a Big River Again, dives into how two...