Why Ontario is experiencing more floods — and what we can do about it

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...

Imagine a complex forestry violation. Say a timber company fails to adequately replant a logging site or to ensure that the contours of a clearcut are not visually jarring from a distance. Now imagine the provincial law-enforcement officer assigned to investigate those violations of provincial laws has no training in how to gather evidence.

Or, think about a suspicious wildfire. Nearby there’s a vehicle that may be connected to the blaze but officers in the field are so poorly equipped they can’t even conduct a check on the vehicle’s registration.

This is the state of affairs for natural resource officers in B.C., the individuals who patrol the province’s forests to enforce a broad suite of natural resource rules, covering everything from trail maintenance to fire bans to monitoring wildlife closures to inspecting logging operations.

According to a “special investigation” by the Forest Practices Board, a government watchdog on provincial forest operations, oversight of two key pieces of legislation — the Forest and Range Practices Act and the Wildfire Act — is suffering due to major gaps at B.C.’s Compliance and Enforcement branch where natural resource officers are housed.

Kevin Kriese, chair of the Forest Practices Board, said there is a concern that officers responsible for monitoring forestry are catching the small, easily handled infractions and missing the big-picture investigations.

“It’s almost like you’re hiring a cop when what you need is a detective,” Kriese, who served eight years as an assistant deputy minister with the province, told The Narwhal.

“Forestry is complicated and you need a mix of people with different skills. They need more of the professionals to handle the complexity of forestry.

“We don’t want to worry about jay walking, to be honest … stepping over the dollars to pick up the pennies and nickels. We’re more worried about the more complex transactions. That’s where the energy should be focussed.”

The Forest Practices Board, a government watchdog on provincial forest operations, emphasizes that the public has the right to expect regular inspections of forestry operations to hold logging companies accountable for their practices.

But there’s no evidence of this happening — despite repeated warnings to government.

“It’s cause for concern,” Doug Donaldson, Minister of Forests, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, said in response to the report.

“Forests are a publicly held natural asset and the public wants to feel confident there’s proper oversight on the activities we approve on the land base,” Donaldson told The Narwhal.

In 2013 the Forest Practices Board complained about a reduction in forestry inspections, and in 2014 reiterated problems with the compliance and enforcement program — both during BC Liberal administrations.

This latest report concludes that the public “cannot be confident” with the branch’s enforcement actions and that “major weaknesses and gaps” still exist.

“Unfortunately, this most recent investigation finds that the situation has not improved and the concerns raised in those earlier reports remain,” the board finds.

Donaldson said his ministry is already implementing a new “delivery model” in which some duties of natural resource officers such as campfire bans, recreation site and trail patrols, and wildlife area closures — are transferred to the Conservation Officer Service, within the Ministry of Environment.

Twenty new conservation officers with the environment ministry were sworn in one year ago, bringing the total to 164 around the province, including those in administration.

“[Natural resource officers] will move away from patrol work and focus on inspections and investigations … rather than just waiting and reacting to potential violations,” he said.

“This is legitimately what the public wants to know about: are the major licencees in compliance?”

B.C.’s Compliance and Enforcement Branch employs about 150 staff province-wide, including 83 natural resource officers conducting inspections, patrols, and investigations.

The officers received almost 4,000 complaints in the 2017-18 fiscal year — virtually all of those involving four pieces of legislation: Wildfire Act (1,185), Land Act (1,060), Water Sustainability Act (930), and Forest Resources Practices Act (722).

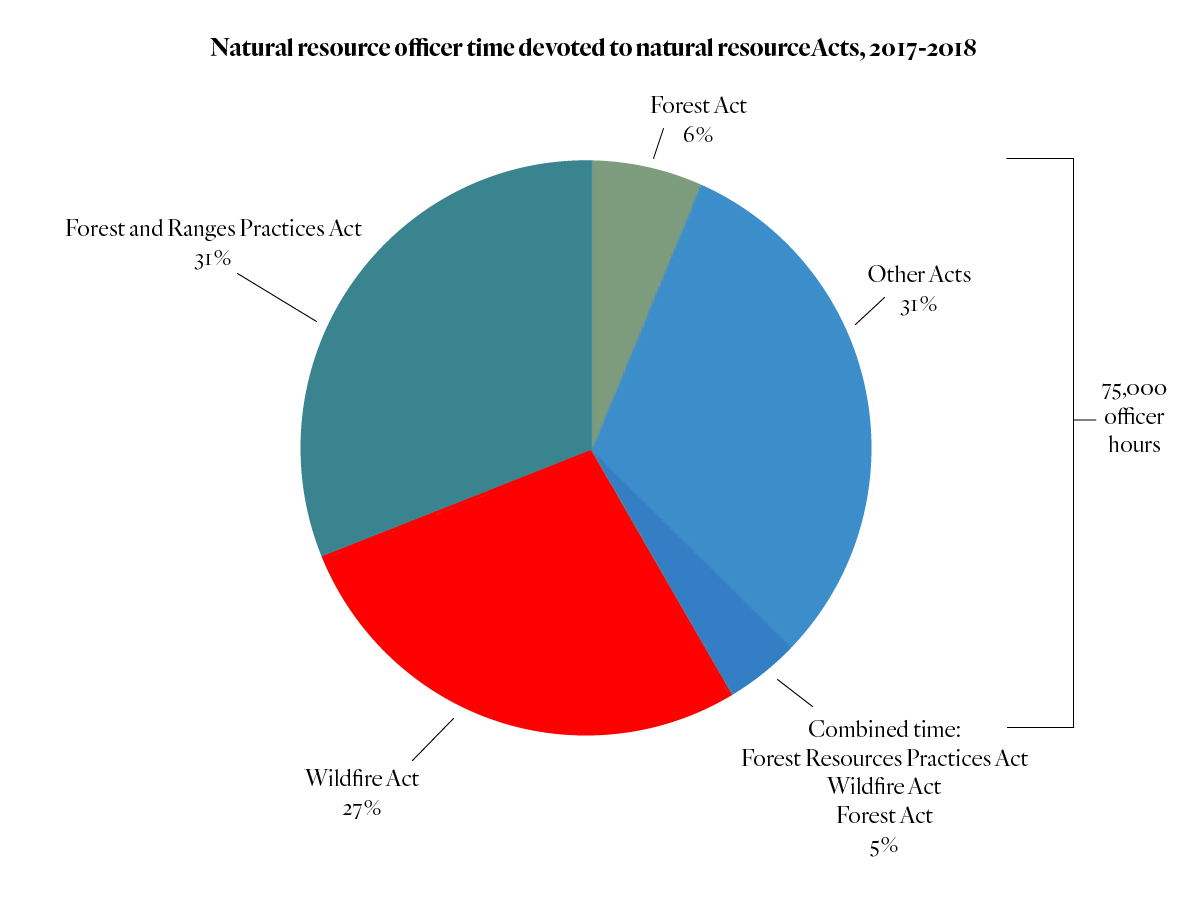

B.C.’s Natural Resource Officers spent nearly two-thirds of their time enforcing the Forest Range and Practices Act and the Wildfire Act, 2017-2018. Source: Forest Practices Board. Graph: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

Officers spent relatively little time investigating woodlots, archaeology and foreshore issues despite these being listed as among the board’s priorities for 2017-2018.

As part of its special investigation, the board heard from natural resource officers that the Compliance and Enforcement branch “has not fully committed to being a fully equipped enforcement agency with all the training, tools and policies needed for all types of enforcement issues they may encounter.”

Forestry laws are complicated and natural resource officers can join the branch without knowing how to properly conduct investigations — and they don’t necessarily receive proper training on the job, either.

Donaldson puts the blame on the former Liberals for gutting the B.C. Forest Service.

“I take the report seriously,” he said. “The legacy of the last government was a decrease in oversight in the forest sector. We’ve got to turn that around for people to feel we’re managing the forests for the benefit of the public.”

Natural Resource officer Denise Blid posts a seizure notice to poached timber. Photo: B.C. Compliance and Enforcement Branch

A report by Sierra Club BC and the Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives in 2010 noted that in less than a decade, the forest service had lost 1,006 positions, or roughly one quarter of its workforce, and that from 2001/2002 to 2004/2005 field inspections by compliance and enforcement staff fell by 46 per cent.

This latest Forest Practices Board report reveals that new natural resource officers often “do not have experience in natural resource management” and are not supported with adequate training opportunities.

“They do not possess the knowledge and experience to identify and investigate the more complex aspects of provincial forestry legislation.”

With experienced staff retiring, mentorship opportunities are also diminishing.

New officers “prefer to issue violation tickets for straight-forward non-compliances, rather than investigate complex non-compliances,” the report says, adding there is a perception among some officers that forestry and wildfire investigations “are too complex, time consuming and difficult to pursue.”

The investigation also found officers have trouble connecting with specialists within the ministry who can help gather evidence and decide if a contravention has occurred.

During summers when patrols are busy reacting to wildfires, oversight of forestry infractions is put on the back burner.

“We think they need to keep their eye on the forestry ball more than they have,” Kriese, who was appointed by Minister Donaldson, said.

The board’s investigation also found the branch “does not have a transparent compliance and enforcement program. It does not regularly or comprehensively report its activities, enforcement actions, outcomes or compliance rates to the public.”

Kriese said the board is not suggesting more money and staff for the branch because there is not enough information available to make that conclusion.

“Without data to analyze compliance rates we don’t know if that’s enough,” Kriese said.

He did note that when the board itself conducts audits of individual forest company operations, it observes “fairly high industry compliance with the legislation.”

In February this year the board audited BC Timber Sales and licensees in the Dawson Creek timber supply area and found practices generally complied with Forest Range and Practices Act and the Wildfire Act.

The audit also found room for improvement to BC Timber Sales’ bridge maintenance, and found problems with two timber sale licence holders related to excessive soil disturbance and the need to complete fire hazard assessments.

Mina Laudan, vice-president of public affairs for the Council of Forest Industries, said in a written statement: “The B.C. forest sector is one of the most highly regulated industries in the province, with the majority of industry’s operations meeting internationally-recognized criteria for environmental management systems.”

However, the Forest Practices Board report makes it clear that industry has its own beefs when it comes to compliance and enforcement issues.

Forest companies see natural resource officers less often in the field these days, resulting in fewer inspections of their operations. When issues do arise, officers are more likely to write enforcement tickets rather than seek a resolution over the phone. Logging companies, the board found, would appreciate being notified when an inspection reveals they are doing a good job.

The board report is troubling news to B.C.’s environmental movement.

Joe Foy, co-executive director of the Vancouver-based Wilderness Committee, is not impressed that under-resourced, inadequately trained officers are tagged with protecting B.C.’s forests, water and wildlife from illegal acts.

The report noted not all officers can query police systems to identify the owner of a motor vehicle or the background of a person of interest in the field.

Foy allows that the NDP minority government inherited a ministry “decimated” by the former Liberals, but says he is still waiting for change.

“Even under the new provincial government the big timber companies are still running the show,” he laments.

The board has asked the Ministry to report back on efforts to improve forestry compliance and enforcement by December 31.

Update: Thursday, May 2 9:21am PST. This story’s first paragraph was updated to clarify the nature of violations under the Forest and Range Practices Act.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

How can we limit damage from disasters like the 2024 Toronto floods? In this explainer...

From disappearing ice roads to reappearing buffalo, our stories explained the wonder and challenges of...

Sitting at the crossroads of journalism and code, we’ve found our perfect match: someone who...