A note from Tanya Talaga

I’ve watched The Narwhal doggedly report on all the issues that feel even more acutely...

The four-year-old caribou is still on her feet, kicking and bucking like a Stampede bronc, as Clements Brace and Conrad Thiessen scramble toward her through the late October snow.

There’s a thin white mist drifting over the ground from the rotor wash of the capture helicopter, but from the open door of a second chopper hovering a few hundred feet above, we have a clear view of the action. With her head and forelegs tangled in a bright orange net, the struggling caribou twists and stumbles as Thiessen, a wildlife biologist with the British Columbia government, quickly closes in. Brace, a camo-clad Indigenous guardian from the Tahltan Nation, runs a few steps behind.

They dodge sideways to avoid a lunge of the caribou’s antlers before swiftly stepping to her side, tackling her by the head and shoulders and muscling her to the ground. The two men have her controlled within seconds, and then we’re banking and dropping, the barren mountains tilting precipitously on the horizon as our pilot spirals down to land.

B.C government biologist Conrad Thiessen wrangles a caribou in the snow as part of a collaborative research project on the Tseneglode herd in the territory of the Tahltan First Nation. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

A helicopter from Canadian Wildlife Capture, carrying a net gunner, pursues the Tseneglode caribou herd. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

The territory of the Tahltan First Nation in northwest B.C. is home to the Tseneglode caribou herd, which boasts a relatively healthy population when compared to the province’s southern herds. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Participants of a collaborative collaring project run in partnership between the Tahltan First Nation and the B.C. government rush to collar, tag and take samples from a captured caribou. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Earlier that morning, we’d been standing with Brace at the Tundra Helicopters base in Dease Lake, in Tahltan territory, talking about how weird the weather had been.

The thermometer had been down to -20 C a few nights before, and on the drive north from Smithers photographer Jeremy Koreski and I had stopped to watch rafts of ice drift beneath the grates of the Stikine River bridge. But the temperatures had warmed again — so much so that rain had fallen at an elevation of 6,000 feet, creating an icy crust in the high alpine of the Cassiar Ranges, where we’d be capturing and collaring at risk northern mountain caribou.

“It’s just strange,” says Brace, one of six Guardians employed by the Tahltan Central Government to monitor and manage wildlife and habitat in the nation’s territory.

“Being local and living here so long, you feel the change automatically. Frick, your feet get soaked nowadays, and they never used to be soaked around this time. It used to be pretty cold.”

Clements Brace (left), an Indigenous guardian with the Tahltan nation, and B.C. government biologist, Oliver Holt, prepare for takeoff at the Tundra Helicopters base. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

The Tahltan Nation received funding from the federal government’s Canada Nature Fund to increase its guardian activities on Tahltan territory. The financial support was used in part to purchase helicopter time and gear to gather data on the caribou herd. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Researchers at the helicopter base are seen here, preparing to head out to remote mountain ranges in search of the Tseneglode caribou herd. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

The big swings in temperature that accompany an increasingly unstable climate can disrupt the signs caribou and other animals rely on for their movement, feeding and denning patterns. “A long time ago they had signs, when to den and things like that. The ground freezing at certain times, and they’d start to dig. Now the ground’s thawed out. It’s really strange how the environment is changing, and I guarantee it has a lot to do with how the animals are changing too,” Brace says.

The project Koreski and I had come to document — collaring 20 caribou from the little-studied Tseneglode herd — is part of the Tahltan Nation’s ongoing work to track how its lands and wildlife are responding to the accelerating effects of the climate emergency, as well as pressures from mineral exploration and hunting, along with unstable predator-prey dynamics.

With the help of its guardian program, introduced in 2016, the Tahltan Nation has been intensifying monitoring and research activities in its territory. When grant money from the federal government’s Canada Nature Fund became available this past year, the Tahltan Wildlife Department purchased helicopter time and the sophisticated GPS collars now arrayed behind us in Tundra Helicopters parking lot. The project to place the newly acquired collars on the Tseneglode herd is a partnership with B.C.’s provincial caribou recovery program and Thiessen and another government biologist, Oliver Holt, are along to help with the work and gather as much data as possible about the health of the herd.

A map showing the territory of the Tahltan First Nation in northwestern B.C. Map: Carol Linnitt / The Narwhal

A caribou from the Tseneglode herd sports a new numbered collar that will now be tracked by the research team. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Ranging through wild terrain that surrounds the small community of Dease Lake, the Tseneglode caribou have long been harvested by Tahltan and other resident hunters. But despite the herd’s range being bisected by the area’s only paved highway — and made increasingly accessible from rough roads built for mineral exploration — the herd’s size and movements have remained unclear. In 2015, a B.C. government survey estimated the population contained 712 animals, making it the province’s eighth-largest caribou herd, but listed its long-term population trend as “unknown.” A few days prior to our arrival, members of the Tahltan wildlife team conducted a survey flight over the Tseneglode range, counting slightly more than 600 individuals.

Though counting animal populations always has a certain margin of error, it’s clear that a lack of data has left the provincial government making management decisions about development, forestry and mining that affect the Tseneglode caribou — and the people who depend on them as a food source — without having much information at hand. Referring to northern caribou populations on the website of the provincial caribou recovery program, the government notes that “efforts to protect and better understand the herds are underway. … However, population data is variable and scarce, so scientists have less confidence in herd size estimates.”

The lack of capacity to collect adequate data is partly a budgeting issue. One of the paradoxes of caribou management in B.C. is that southern herds on the edge of extirpation receive much more attention and investment than still-healthy herds in the north. In 2017-2018, for example, the government spent $386,000 on management and monitoring of the 147-member Columbia North herd in the Kootenays, and only $37,000 on the far larger Tseneglode herd. Given the ongoing funding shortages, monitoring projects that operate in collaboration with First Nations, such as the Tseneglode collaring effort, may help fill some of the gaps.

Even with limited information, however, it’s widely accepted that caribou are in trouble throughout most of B.C. One century ago, there were an estimated 40,000 caribou in the province; today, there are estimated to be less than 18,000. Over 30 of B.C.’s 47 surviving caribou herds have decreasing or unknown population trends, and seven herds have been extirpated since 2003. The government cites climate change, habitat degradation and increased predation as likely drivers of the decline. Over the years, the Tahltan and many other First Nations have been directly affected by the loss.

These numbered caribou collars will be used to track individual caribou and will provide data on herd size, range and mortality events. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

The Tahltan First Nation has relied on the Tseneglode caribou herd for generations. Data captured through the collaring program will be shared with the Kaska and Tlingit First Nations as part of the 3 Nations partnership. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

While Thiessen and Oliver prep capture nets, guns and sampling gear, and pilots Clint Walker and Bill Oestreich run through their safety checks, Brace tells us about some of the changes he’s witnessed over the course of his life.

“We’re just not seeing caribou in areas where they used to be plentiful,” he says. “There used to be lots of caribou right by the road. I go up there every year hunting to get one for my grandparents, and you could see the herd getting smaller and smaller. In the past you’d just drive up the highway and walk off the road, and they’d be there. Whereas now, you have to basically hire a helicopter to go get a caribou.”

“It’s the same with the moose, too,” he continues. “My grandparents used to go hunting up to Cottonwood, which is probably 90 kilometres from here, and they’d see at least 40. Now you’d be lucky to see even two. So the Elders are definitely talking about changes in the way of the animals.”

That’s where the collaring project comes in. The data will be shared by the Tahltan with the Kaska and Tlingit First Nations, all members of the 3 Nations partnership.

“We can join together on this project,” Brace says, “and see what effects are happening.”

Brace says Indigenous guardians are not seeing caribou in regions where they used to be plentiful. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Brace is part of the Tahltan First Nation’s guardian program, which supports the management and monitoring of natural resources in the nation’s territory. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

A curious fox takes notice of the research team at the helicopter base. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

The peaks of the Cassiar Ranges provide habitat to caribou, Stone sheep, foxes and wolverines. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Evening light falls in the range of the Tseneglode caribou herd. In recent years, monitoring efforts have shown the population has a far greater range than previously thought. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

For the Tahltan, there’s considerable value in bolstering their countless generations of first-hand knowledge with collaring data and other remote sensing information that modern science can provide.

“Data always alleviates some of the unknown stresses when you’re a manager of the herd,” says Lance Nagwan, the wildlife director for the Tahltan Central Government.

Nagwan says caribou are culturally significant to the Tahltan and have been a reliable food source to the nation “for thousands of years.” He said the COVID-19 pandemic has emphasized how important caribou — or hodzih, pronounced like hoody, in Tāłtān — are for local food security. “It’s not good for us to see them in jeopardy or being stressed in any way, and with the information we’ll get from these collars, we can have better understanding, better management and better stewardship.”

GPS collaring has already provided some important insights to the Tahltan guardians. Two years ago, in the first Tseneglode collaring effort, the Tahltan wildlife team placed 12 collars in the field. They soon found the animals were travelling more widely than expected, ranging as far north as Good Hope Lake in Kaska territory, almost 140 kilometres to the north — meaning there’s a much larger area in which impacts on the herd need to be observed.

“Their home range is a lot bigger than we assumed,” Nagwan notes. “So that’s another thing for us to pay close attention to.”

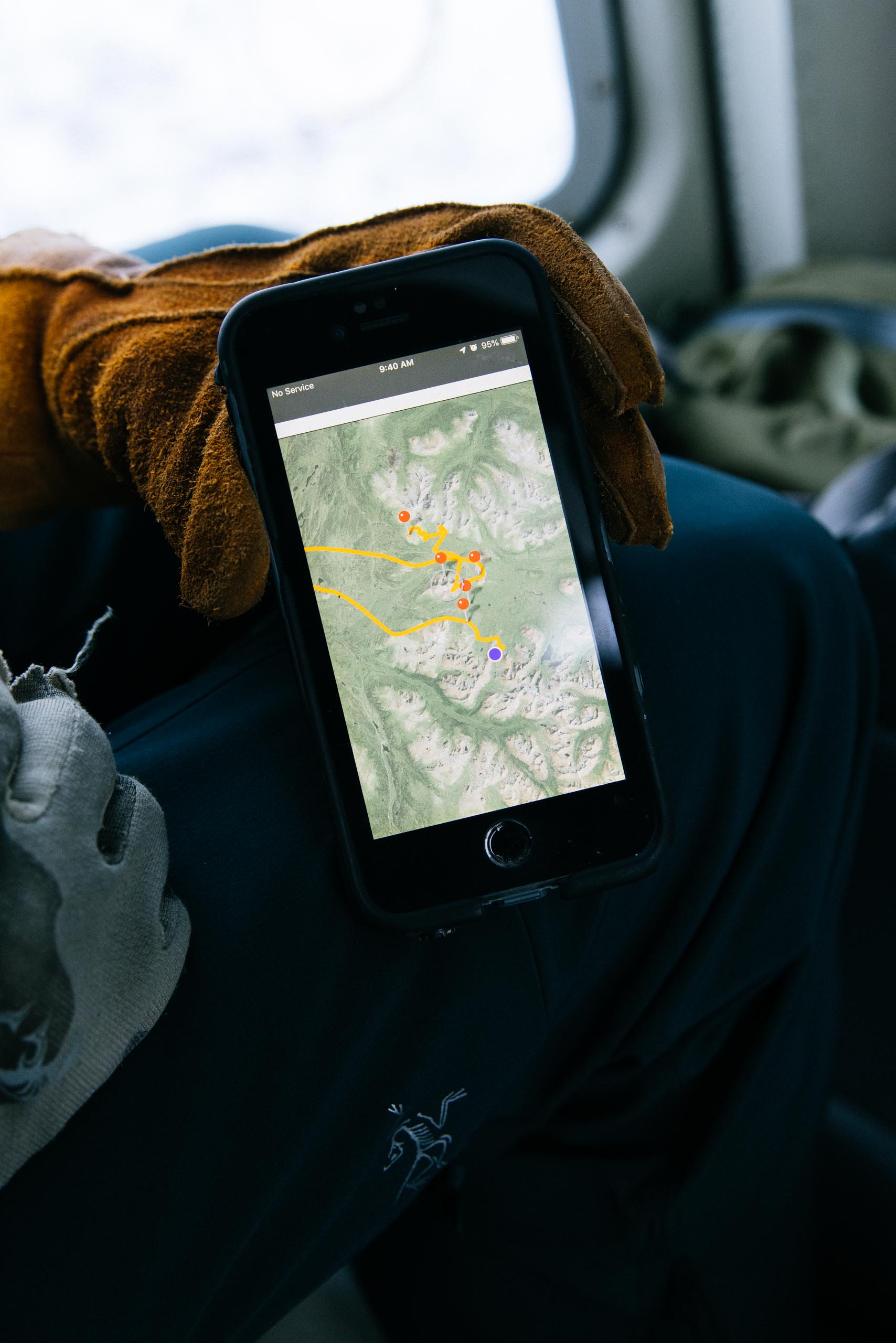

While providing more detail about the herd’s movements and patterns of habitat use, the collars will also help more precisely estimate its total population. Once the GPS collars are placed on the animals, gathering data is as simple as watching coloured blips on a screen. For a period of three years until they automatically release and drop off the animals, the collars transmit up-to-the-minute location data as the caribou go about their lives, and provide notification of a “mortality event” if a caribou stops moving for a certain number of hours, allowing the Tahltan guardians to quickly respond and investigate. As part of the Tahltan curriculum, schoolkids will also be naming the collared Tseneglode caribou and following their movements online.

But as we’d soon learn, getting the collars placed is far from child’s play. After personal temperature checks and a briefing on the government’s approved COVID-19 protocols, we mask up, cram in the last of our gear, squeeze into the choppers and lift away.

Net guns are loaded with specialized wildlife capture nets for use in the research project. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Wildlife biologist Oliver Holt works with the provincial government’s caribou recovery program. The government considers the long-term population trend for the Tseneglode caribou herd “unknown.” Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

GPS coordinates are used to track the collared caribou. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Holt takes notes on a caribou collared and sampled in the field. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

A 2015 B.C. government survey estimated the population of the Tseneglode caribou herd at 712 animals, making it the eighth-largest herd in the province. A recent aerial survey conducted by the Tahltan Nation counted 600 individuals. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Once aloft, we speed over spruce forest and snowy valleys as we head for the areas where the Tahltan survey flight had found groups of caribou the week before. Below, we see the scar of the Jade-Boulder road and a maze of illegal ATV tracks, both of which have been leading more prospectors and hunters into the Tseneglode range in recent years.

Searching farther into the backcountry, Oestreich spots the first group of caribou on an alpine crest, and the work begins.

As we watch from a distance, the agile MD 500 helicopter descends on the caribou, which break into a run. Thiessen, the net gunner on this project, hangs out an open door as Walker, an experienced capture pilot who works for a specialty contractor called Canadian Wildlife Capture, flies as close as possible to the fleeing animals. He deftly uses the helicopter to separate an adult cow from the group; for a successful shot, a caribou must be on its own with the gunner placed just three metres or so above.

Though Walker has been flying for 24 years and says capture work is “about as much fun as you can have in a helicopter,” doing it safely at high speed is difficult and dangerous — think catching a deer with a Jeep, but with alpine wind, blowing snow and spinning blades added to the mix.

Pilot Clint Walker says flying for wildlife capture is “about as much fun as you can have in a helicopter.” Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Walker angles the helicopter to try to get within three metres of the caribou for a successful shot. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Author Malcolm Johnson (centre) and biologist Oliver Holt (right), run from their helicopter to support Theissen and Brace in their collaring and caribou sampling efforts. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

A caribou is successfully netted. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

The safety of the animals is a key consideration during the collaring process. Tranquilizing caribou is considered more dangerous to the animals, so they remain awake and alert throughout the collaring process. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Brace prepares an ear tag. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Caribou are hobbled and blindfolded during the capture process to prevent injuries to the animals and the research team members. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

“Everyone has an essential role,” says Thiessen, who’s been doing this work for 12 years and is now the senior wildlife biologist for B.C.’s Skeena region. “But the pilot is really about 90 per cent of the capture. He puts you in the spot, and as a gunner it’s just a matter of picking the right time to shoot.”

There’s often only a split-second to make an accurate shot, with the capture net fired forward by a specially-designed gun loaded with .303 blanks. The first capture we watch isn’t quite textbook — a 30-knot wind is whipping over the ridges, making the shot more challenging than usual, and the net snags on the caribou’s antlers without catching its feet. We see it streaming across the snow in a streak of orange as the heli circles around for a second shot.

The next one’s on target, and within a few minutes Brace, Thiessen and Holt have the caribou down on the snow. They blindfold her to keep her calm, extract her legs from the net and secure them with flexible hobbles. Then, working as quietly and efficiently as possible, they place the collar around her neck, attach a permanent ear tag and collect samples of blood, hair, skin and feces. There are other health checkups too — they use a plastic comb to check the caribou for ticks and examine its teeth to determine its age. Government guidelines stipulate that the entire process be performed in less than 15 minutes.

Thiessen combs a caribou to check for ticks. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Holt uses a syringe to distribute caribou blood samples to vials for further research. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Caribou blood, seen here on the snow, is drawn from individual animals from a leg vein and will be sent to the B.C. wildlife health program to test for disease, pregnancy and nutrition. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

A caribou is held down by a wildlife capture net. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

The caribou aren’t sedated during the capture. Despite their struggles while they’re being worked on, the use of tranquilizer darts is considered more dangerous to the animals. During a survey of a herd just south of the Tseneglode several decades ago, for example, a calf was killed by an errant dart and an adult female injured by slipping on ice as the drugs took effect. The current technique of net capturing isn’t without its risks, however — the mortality rate during captures is around two per cent, Thiessen notes, usually from broken limbs or necks suffered during the pursuit. But for Thiessen and other wildlife biologists, “the value of having a better understanding of the population as a whole outweighs that cost — because if we don’t know what’s going on with the population, we can’t help it.”

After the first few captures, the team falls into a predictable rhythm, and I’m able to step in to help.

Brace, Thiessen and Walker land first and get the caribou down, then our helicopter follows. Holt and I climb out, duck under the rotors and plunge through the snow to help control the caribou as she’s extracted from the net — not always an easy task, as female caribou are powerful animals, averaging around 200 pounds, with sharp hooves and antler tines that, as we find out, can easily pierce a work glove and the skin beneath. Before the hobble straps are on, it often takes all of our strength to hold the animal in place, everyone’s breath fogging in the air as the caribou kicks out and its chest heaves up and down beneath us. When an animal needs to be repositioned to get the collar placed or to keep it from sucking in snow, Walker and Oestreich jump in too.

It’s backcountry rodeo, and as I learn from first-hand experience, everyone goes home with a few aches and bruises at the end of the day.

From left to right: Brace, Thiessen and Walker. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Helicopter pilot Walker gathers up a net for reuse. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Caribou captured by the team are fitted with permanent ear tags. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

For two full days, we fly circuitous routes through the Tseneglode range, our eyes scanning the alpine and buckbrush for the gangly outlines of caribou.

Transiting between capture zones, we get a cinematic view of some of the most beautiful terrain I’ve ever seen and the wildlife that inhabit it: moose foraging in the trees, Stone sheep on rocky skylines, a fox and wolverine scavenging a carcass in faded pink snow. At one point, we glimpse an injured bull caribou limping below us at the treeline. “Yeah, that one won’t be long for this world,” mutters Oestreich over the headset.

When we descend to each capture, the thud of the rotors and the scale of the landscape soon give way to hushed quiet and a sharp focus on the smallest details: the soft chestnut of caribou fur under our gloves, Thiessen showing Brace how to draw blood from a leg vein, Brace soothing a mother caribou with a rub of the neck. While we work to hold one caribou still, Brace reminds me to ease up as she calms: “You’re a bit on her lungs there, bud.”

Biologist Conrad Thiessen places his hand on a caribou. The researchers attempt to sooth the creatures as they work quickly to gather samples. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

A caribou is fixed with a collar. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

After samples are collected and the collar is attached, caribou are released from their binds and blindfold to run off. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

As the work finishes for each animal, the blindfold and hobbles are removed. Keeping hold of their antlers as they clamber to their feet, Brace points them to safety and lets go. They trot off away from us, some of them prancing only a few paces before stopping to look back, as if wondering, “what the heck just happened?” Then they disappear into the willows, or canter uphill until they’re over the ridge and gone.

On the last night of our work, I join Thiessen in his room at a motel in Dease Lake. There’s a can of beer on the table and a sprawl of gear on the floor as he spins tubes of caribou blood in a small centrifuge. From here, the tubes will go to the B.C. government’s wildlife health program, where they’ll be used to test for pregnancy, nutrition, the presence of disease and other indicators of caribou health. This is the less glamorous majority of conservation work, the detailed science that’s done by people who love wild animals and the habitat on which they depend.

While he sorts through samples, Thiessen tells me these projects aren’t always enjoyable for him — doing it safely, he notes, takes a level of focus that doesn’t leave a lot of time for fun or reflection. But he likes the teamwork aspect of it, particularly working with Indigenous guardians like Brace and others with whom he’s collaborated throughout the north.

The government’s caribou strategy has a goal to “align science and recovery approaches with Canada and Indigenous governments where appropriate.” For Thiessen, who hopes to move toward a formal data sharing agreement with the Tahltan, there’s also a simpler and more personal guiding principle.

“It feels good at the end,” he says, “when we did it together and we’re all there together.”

Thiessen told The Narwhal he hopes more research collaboration can occur between government and the Tahltan Nation. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Caribou hooves are uniquely well-suited to navigating deep snow. Photo: Jeremy Koreski / The Narwhal

Given how long First Nations governments have been sidelined from conservation and land management in Canada, and how much Indigenous knowledge is still marginalized by Western science, doing shared work on the land seems like a promising step in the right direction.

Though there’s still much farther to go, striving for stronger collaboration and more effective co-management is a goal shared by the Tahltan.

As Brace tells me before we leave, it’s in everyone’s interest to “work together and expand our horizons and make it better for all of us.”

“With all the scientific knowledge we’re starting to gather as guardians I think we’re going to have a good effect,” he continues. “And there are some changes that need to be done, from what we know as Tahltan and what we’ve seen as guardians on the land. But I think we’re at the point where it’s not too late to make those changes. So we’re taking those steps, and we want to do it right.”