Bill 15: this ‘blank cheque’ legislation could dramatically change how B.C. approves major projects

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...

Will 2025 be the year the B.C. carbon tax dies? In his first press conference of the year, B.C. Premier David Eby promised British Columbians won’t pay “any additional carbon tax,” despite an annual increase in the tax scheduled for April 1.

“I will make sure that the April 1st increase is netted out in some way to make sure that British Columbians don’t face additional costs this time when they can least afford it,” Eby told reporters on Tuesday.

Once a staunch defender of B.C.’s consumer carbon tax — the first to be implemented in North America — Eby changed his tune last fall as a provincial election loomed. In September, Eby said a re-elected BC NDP government would eliminate consumer carbon pricing — as long as the federal carbon price program was rolled back first.

BC Conservative Leader John Rustad claimed credit for Eby’s sudden reversal, calling it “a desperate attempt to salvage his sinking political ship.” Rustad’s upstart party, which went on to win 41 seats in the October election and is now the official opposition, ran on a promise to immediately scrap the carbon tax and is keeping up the pressure.

How Eby plans to offset April’s carbon tax increase is unclear. In response to The Narwhal’s request for clarification, the Finance Ministry sent a statement citing the climate action tax credit, which about 65 per cent of B.C. households received last year. The ministry did not say whether any new measures will be implemented this year.

What to do about the beleaguered carbon tax is just one of the big environmental decisions Eby’s government is facing this year.

What else is in store for 2025? Read on.

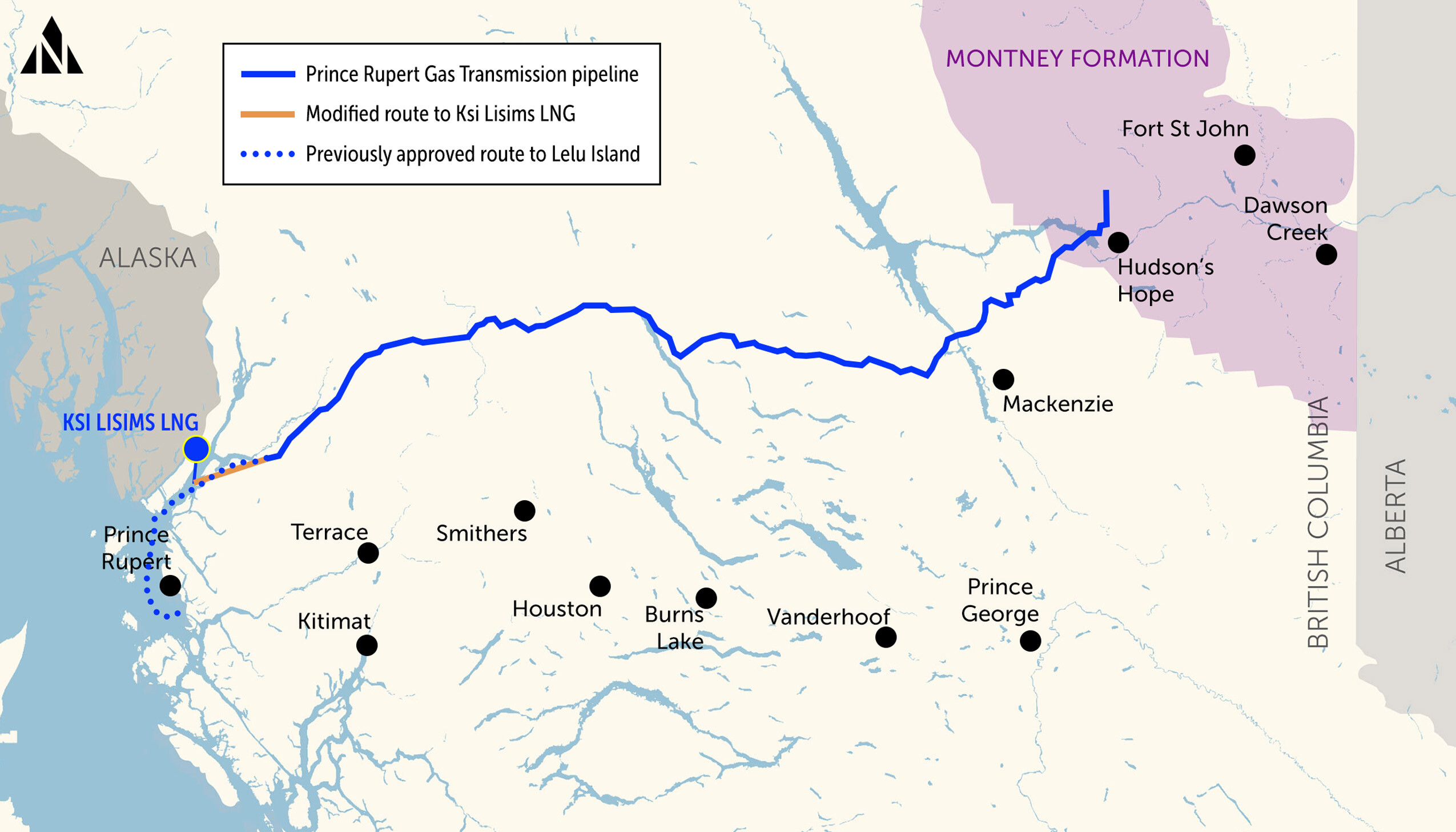

One month before Christmas, the Prince Rupert Gas Transmission (PRGT) pipeline hit a make-or-break milestone. The 800-kilometre pipeline would transport fracked gas from B.C.’s northeast to the proposed Ksi Lisims liquefied natural gas (LNG) export facility on the Pacific coast near the Alaska border.

On Nov. 19, the Nisg̱a’a Nation and Western LNG, the pipeline’s owners, asked the B.C. Environmental Assessment office to determine whether the project meets the “substantially started” designation, which would lock in the pipeline’s 2014 environmental assessment certificate. The assessment office will evaluate physical work done on the project up until Nov. 25, as well as other unspecified factors, to determine if the project must undergo a brand new environmental assessment. The office expects to release its findings this spring.

When the PRGT pipeline underwent an environmental assessment a decade ago, it was for a different route to a different LNG project. Despite the pipeline’s name, it will no longer go to Prince Rupert, B.C., but to the north end of Pearse Island near the Nass River estuary, close to the Alaska border.

The area is the site of the proposed floating Ksi Lisims LNG export facility, which would be capable of producing up to 12 million tonnes of LNG annually — making it the second largest LNG facility in B.C. after LNG Canada. Ksi Lisims, backed by the Nisg̱a’a Nation, is still undergoing a provincial environmental assessment and has not yet been approved by the B.C. government.

In late August, as PRGT pipeline construction work began on Nisg̱a’a territory, Hereditary Chiefs from Gitanyow Nation set up an ongoing blockade to stop traffic related to the project from crossing their territory, which borders Nisg̱a’a lands. The chiefs are among those who say they will take whatever action is necessary to stop the project.

If the PRGT pipeline is delayed by a new environmental assessment, the Ksi Lisims project will face more uncertainty.

The Ksi Lisims project is in the final stages of a B.C. environmental assessment following public comment on a draft environmental assessment certificate and report. Once those two documents are finalized, they will be submitted to B.C.’s environment and energy ministers, starting the clock on a 30-day timeline for the government to make a final decision about whether to approve the project.

In October, Gitanyow Nation Hereditary Chiefs submitted an application for judicial review to the B.C. Supreme Court, alleging the assessment office failed in its duty to consult about the Ksi Lisims project and was negligent in its obligations to protect fish species when it concluded the project does not pose a threat to Nass River salmon.

“This project threatens our food security and [the] government has denied Gitanyow a role in decision making,” Simogyet (Hereditary Chief) Malii Glen Williams said in a statement.

The court filing states that assessment office staff rejected the chiefs’ request to pause Ksi Lisims’ environmental assessment to allow more time to study the potential impacts of the project on juvenile salmon in the Nass River. The March 2024 dismissal of the chiefs’ request concluded “there is no reasonable possibility that Gitanyow or its [constitutionally protected] rights will be adversely affected by Ksi Lisims LNG.”

Hup-Wil-Lax-A Kirby Muldoe, chair of the Gitxsan Lax’yip management office, called the assessment office’s conclusion “a blatant disregard for the watershed-wide impacts to salmon” potentially posed by the floating LNG terminal.

On the campaign trail last fall, the NDP promised to continue work to fulfill the recommendations from its 2020 old-growth forest strategic review, which called for a major shift in how B.C. manages its forests. According to a May update from the province, only two of the old-growth review’s 14 recommendations were at an advanced stage of implementation, while nearly half were still in the “initial action” stage.

The review resulted in logging deferrals in pockets of old-growth forest around the province, mostly with the support of local First Nations. Deferrals included the Fairy Creek area in Pacheedaht First Nation territory.

In 2021, the largely intact old-growth valley on the southwest coast of Vancouver Island became the site of the largest civil disobedience action in Canadian history. Following more than 1,100 arrests, and at the request of Pacheedaht First Nation, the B.C. government deferred just over 1,180 hectares of Fairy Creek old-growth forest from logging in June 2021.

Providing permanent protection to the Fairy Creek watershed is part of the co-operation agreement between the NDP and the BC Green caucus announced in December. The agreement says the B.C government will “move forward to ensure permanent protection of the Fairy Creek watershed” in partnership with the Pacheedaht and Ditidaht First Nations and “pending the resolution of existing legal proceedings and community negotiations.”

While deputy premier Niki Sharma recently emphasized the commitment to work toward permanent protection of the watershed does not mean the valley’s fate will be decided any time soon, Green Party MLA Rob Botterell said the caucuses hope to “get to yes on protection” in 2025.

“We want to be as open and transparent with everyone about the types of issues that will need to be dealt with,” Botterell told The Narwhal. “As we work together on that, we’re going to find out just how quickly we can address those types of issues.”

The current Fairy Creek logging deferral expires on Feb. 1. The Narwhal asked the B.C. Ministry of Forests if the deferral will be extended under the agreement with the Greens. A ministry spokesperson said in an email that cabinet will “consider” the deferral order before it expires.

The agreement also commits the NDP government to work with the BC Greens to undertake a review of B.C.’s forests, with First Nations, workers, unions, business and community, “to address concerns around sustainability, jobs, environmental protection and the future of the industry.”

The two parties will work together to establish the terms of the review, which are subject to the approval of both. The agreement says the Greens will be involved in all elements of the review and the resulting report will be made public within 45 days of completion, but it lacks a timeline for the work to be done.

Another looming deadline for the NDP government was set by a 2023 court decision in response to a legal challenge brought by the Gitxaała Nation and Ehattesaht First Nation. The nations argued B.C.’s mineral claim staking system is a “colonial holdover”.

The province’s current online system allows almost anyone to make a mineral claim with a few clicks and a fee. There is no duty to consult or notify relevant First Nations before making the claim or exploring the area with handheld tools.

In September 2023, the court sided with the Gitxaała and Ehattesaht and gave the province 18 months to consult with First Nations and change the current claim-staking process to include the duty to consult. This March will mark 18 months since the court decision, so changes to the Mineral Tenure Act and the online staking system could be introduced as soon as the legislature resumes sitting.

The changes come as 17 new critical mineral mines are proposed in B.C. The province is home to deposits of 16 of Canada’s national list of 34 critical minerals, a broad term covering a range of materials needed to produce electronics, including cell phones, computers, wind turbines, solar panels and batteries — crucial components for the energy transition.

The NDP government is also in the process of developing broader reforms to the Mineral Tenure Act in order to align the legislation with the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. The Mining Ministry is still in the process of gathering information on those changes, according to a government website about the reforms, and does not expect to introduce changes until the fall of 2026.

The B.C. government’s hopes to advance the critical minerals sector and electrify gas liquefaction plants hinge on plans to build a new publicly funded transmission line to boost power to the province’s northwest.

The $3-billion North Coast transmission line would run from Prince George to Terrace and provide hydroelectricity for a range of industrial customers, including LNG Canada, Cedar LNG, the Port of Prince Rupert, hydrogen projects and new metal and critical minerals mines. B.C. wants federal taxpayers to cover half the cost.

Electricity for the high-voltage line would come in part from the publicly funded $16-billion Site C dam on B.C.’s Peace River. As The Narwhal previously reported, BC Hydro has suggested replacing an environmental assessment for the North Coast transmission line with a speedier “alternative streamlined process.”

Energy and and Climate Solutions Minister Adrian Dix is responsible for oversight of the project, which rated a mention in a brief list of ministerial priorities the government released on Nov. 18, the day the new NDP cabinet was sworn in.

“I think it’s very exciting work,” Dix said of his new responsibility for the transmission line, which will affect property owners, farmland, waterways and at-risk species. “[It’s] very important for economic development projects, but also for climate change … for jobs and clean energy.”

The 2024 election campaign also saw the NDP stand by its commitment to protect 30 per cent of the province’s land by 2030, as part of global efforts to stem unprecedented biodiversity loss.

The government will achieve the protection target partly by creating new Indigenous protected areas, according to the 2022 mandate letter for the minister of Water, Land and Resource Stewardship. Rookie MLA Randene Neill is now in charge of the portfolio.

The province has plenty of work to do in order to achieve its 30-by-30 goal. In December 2023, B.C. reported 19.7 per cent of land in the province had been conserved through protected areas such as provincial or national parks or other measures.

Not all of the measures prevent development entirely, but the overall intention is to protect biodiversity. The Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society has raised concerns that some areas the provincial government counts towards B.C.’s conservation targets don’t meet biodiversity goals and shouldn’t be included.

“We are hoping that the next government will continue the commitment that is laid out in the tripartite nature framework agreement to protect 30 per cent by 2030,” Tori Ball, the conservation director with the B.C. chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society, told The Narwhal in September. The agreement, announced in November 2023, commits the federal and provincial governments and the First Nations Leadership Council to advancing ecosystem health and biodiversity conservation in a way that integrates the rights and stewardship roles of First Nations.

During the NDP’s previous term, protected areas increased by less than half a percent, while 1,952 species and ecosystems are officially at some risk of extinction in the province, according to the B.C. government’s conservation data centre. Species at risk of extinction in B.C. include spotted owls, southern mountain caribou and southern resident killer whales.

In November 2023, the NDP government released a draft biodiversity and ecosystem health framework. It said the framework would set the direction “for a more holistic approach to stewarding our land and water resources” and eventually lead to legislation to protect biodiversity.

Over the past few years, the government announced new protections in Clayoquot Sound, the Incomappleux Valley’s inland temperate rainforest and the expansion of the Klinse-za / Twin Sisters Park in the province’s northeast. But the NDP also walked back some significant conservation plans in the lead-up to the Oct. 19 election, after facing backlash over proposed changes to the Lands Act to bring the legislation in-line with the province’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act.

B.C.’s Environmental Assessment Act will be under the microscope this year.

By law, the act — which outlines how most major projects will be evaluated and monitored, as well as compliance and enforcement measures — must be reviewed every five years and the clock for the latest review started ticking on Dec. 16, 2024.

As of last month, the environmental assessment office was consulting with First Nations on the review and getting newly appointed Environment and Parks Minister Tamara Davidson up to speed, according to a statement from the ministry.

“A formal announcement on the next steps of the Act Review process — and how First Nations and all interested parties can participate — will be announced in spring 2024,” a ministry spokesperson said in an email.

The last update to the act took effect in Dec. 2019, shortly after the passage of the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. The revamped Environmental Assessment Act reflects that landmark legislation in several ways, including by directing the Environmental Assessment Office to support reconciliation by “recognizing the inherent jurisdiction of Indigenous nations and their right to participate in decision-making in matters that would affect their rights” through representatives they choose.

The updated act added new options for First Nations to participate in the assessment process — including the option to express consent or lack of consent to projects. It also gave the Environment Minister the option to allow First Nations to conduct their own environmental assessment for proposed projects under certain conditions. It’s not clear what those conditions are.

Once this year’s review is complete, the province will decide what changes, if any, will be implemented. Those changes will likely be introduced via a bill in the legislature in 2027 and could take effect in 2028.

— With files from Ainslie Cruickshank and Matt Simmons

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...

Between a fresh take on engagement and our new life on video, our team is...

The public has a few days left to comment on Doug Ford’s omnibus development bill....