Two blank cheques: are Ontario and B.C. copying the homework?

Governments of the two provinces have eerily similar plans to give themselves new powers to...

B.C. permitted clearcut logging in the critical habitat of the Columbia North caribou herd, the sole herd out of the southern group of 17 imperiled southern mountain caribou herds to have an increasing, rather than decreasing, population.

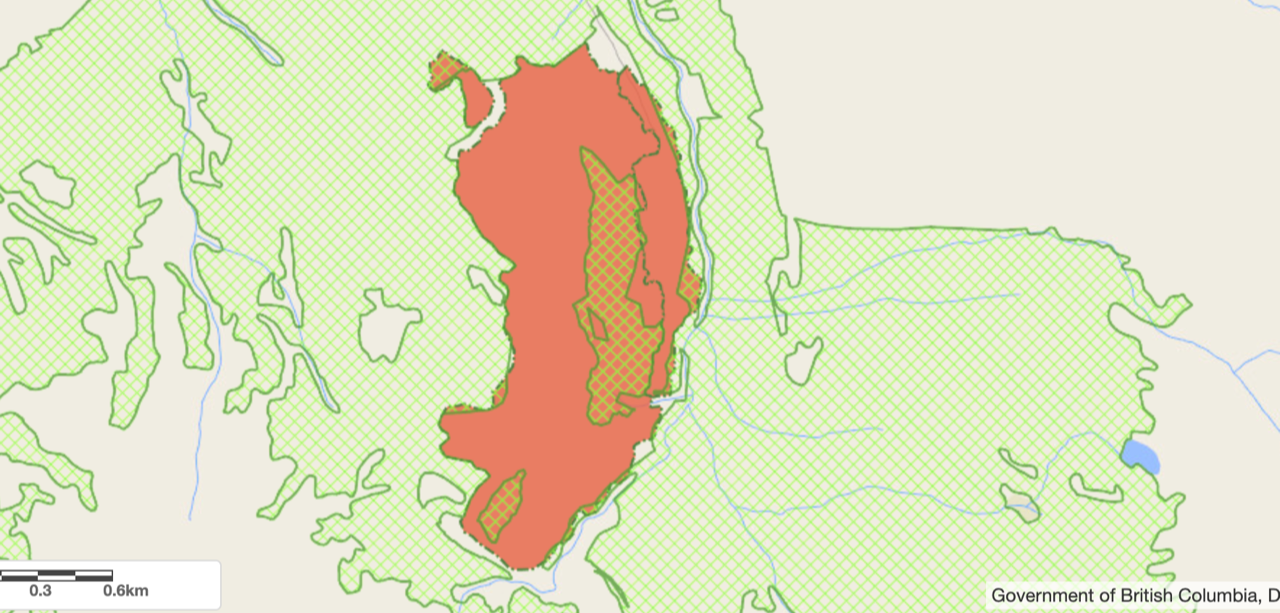

Eddie Petryshen, a conservation specialist with the environmental advocacy organization Wildsight, told The Narwhal he was shocked to find an approved cutblock in the Wood River basin, north of Revelstoke, which eats into the winter range of the Columbia North herd by more than 60 hectares.

Petryshen — who identified the cutblock from satellite map overlays, allowing him to compare approved cutblocks with critical caribou habitat — discovered 5.3 hectares of the area had already been logged, something he confirmed with the provincial government and company Downie Timber.

“I often go through cutblocks and where they are in relation to caribou habitat and this particular block stood out,” he said. “The Wood River is a really high value area for caribou and that particular basin was unroaded previously.”

All of B.C.’s southern woodland caribou herds — divided into north, central and southern groups — are teetering on the brink of extinction. The latest population figures, compiled by the provincial government last October, estimate just 1,254 animals remain in the southern region — down from about 2,500 in 1995.

Since 2006, six of the 17 southern herds have been listed as extirpated, meaning they are locally extinct. Seven herds are listed as decreasing and three are listed as stable, although with very small numbers.

With just 184 estimated individuals, the Columbia North herd is the only herd listed with a current population trend of “increasing.”

Yet the B.C. government is still approving logging cutblocks that overlap critical caribou habitat or require the construction of logging roads through protected areas that grant predators easier access into disappearing caribou range — and not just in the Wood River basin.

In his work for Wildsight, Petryshen has documented numerous other cutblocks overlapping critical habitat, many of which were auctioned by the government agency BC Timber Sales.

“It is pretty significant stuff,” said Petryshen, pointing out that one of the problems with current regulations is that cutblocks overlapping protected areas can be approved if they do not exceed five hectares.

“So what I am finding is a bunch of these cutblocks that overlap by two or three or four hectares. They are nibbling at these protections and doing it without actually replacing it,” said Petryshen.

“It’s kind of shocking,” he said.

“If we can’t protect caribou within provincially designated caribou habitat, where can we protect them?”

Under Canada’s Species At Risk Act, wildlife populations must be prevented from going extinct. B.C. is one of the few provinces in Canada that does not have provincial endangered species legislation and so in 2018, when the federal government threatened to step in to protect B.C.’s caribou populations, the province was compelled to take action, releasing a caribou recovery plan that was roundly criticized. The plan was critiqued for failing to implement strong measures to protect critical caribou habitat from industrial incursion.

In 2020 the province also reached a much-delayed caribou partnership agreement with the federal government and select B.C. First Nations that aims to pull six caribou southern mountain herds from the central group back from the brink of local extinction. The agreement led to some concerns that other dangerously small caribou herds, such as those populations in the south, might be sacrificed to continuing industrial development — in particular forestry.

Even in the wake of B.C.’s 2018 caribou recovery plan, numerous logging cutblocks have been approved in critical caribou habitat throughout the province’s south.

Habitat loss is accepted as the major cause of Western Canada’s caribou decline, with a recent study concluding caribou lost twice as much habitat as they gained over the last 12 years, driven by logging, road building, climate change and wildfire.

Southern mountain caribou are identified as threatened under the federal Species At Risk Act and, under federal rules, B.C.’s recovery strategy should effectively protect critical habitat.

“Human activities should be managed so that there is a high degree of certainty that caribou and caribou habitat will not be impacted, degraded or destroyed,” the province’s caribou recovery website acknowledges.

Yet B.C.’s caribou recovery plan does not extend to a ban on logging or mining — even in areas that are supposed to be protected under special orders or identified as ungulate winter range, which is defined by the province as “an area that contains habitat that is necessary to meet the winter habitat requirements of an ungulate species.”

A 2020 study found that 909 square kilometres of critical habitat for southern mountain caribou was logged during the five years after the herds were legally identified under the Species at Risk Act.

Where logging or other industrial activities are permitted, offsetting and mitigation measures are supposed to be employed to make up for incursions into caribou habitat. Petryshen said what he’s seeing out on the ground shows that is not happening.

A road about five kilometres long has been cut into the Wood River cutblock by Downie Timber, a subsidiary of the Gorman Group.

Petryshen said there is no sign that the road is being decommissioned now that logging is complete or that efforts are being made to stop wolves and cougars travelling into the area where caribou feed. There is also no indication replacement habitat of higher or equal value has been added to the ungulate winter range as is supposed to happen when caribou critical habitat is disturbed, he added.

Petryshe said he is concerned that small incursions into critical habitat are not tracked and there is little government oversight or insistence that the habitat be replaced and roads rehabilitated.

“There’s no process that the province has undertaken to identify a replacement of those logged areas,” he said.

Darcy Peel, director of strategic initiatives with the provincial species at risk recovery branch and former director of the caribou recovery program, said forest companies usually obey the rules around ungulate winter range and wildlife habitat areas and he is confident incursions into no-harvest areas are caught and penalized.

“But there is a misconception that all [Ungulate Winter Ranges and Wildlife Habitat Areas] are no-harvest areas,” he said. “There are many that allow some harvesting to occur under heightened rules or special practices.”

Also, some formerly protected areas were exchanged because mountain pine beetle infestations meant they were no longer functional as caribou habitat, while other areas were hit hard by wildfire, Peel said.

“That brings in climate change and the acknowledgement that things are changing on the landscape. The big disturbances have become more frequent and, perhaps, there are places that are not going to come back the way they were before,” he said.

Landscape conditions drive the health of caribou herds and the provincial emphasis is on protecting older, intact forests, reducing the number of roads and restoring areas where there has been industrial disturbance, said Peel, acknowledging that additional protected areas and intense restoration work is still needed in some areas.

“The challenge is doing that on a working landscape, so we work with forest companies and there is still further work to do on that. We are starting to put big restoration plans in place and there is much, much, much more to come,” Peel said.

The area north of Revelstoke is a hot spot for the conflicting values of logging and caribou protection because old-growth forests rich in cedar and hemlock are prized by industry, while also providing vital caribou habitat.

Overall, B.C.’s caribou population has dropped from an estimated 45,000 to 15,000 over the past century. Columbia North is one of the few remaining viable herds, with 184 animals that interact with the neighbouring Wells Gray and Groundhog herds, but only 40 per cent of the critical habitat is protected through Ungulate Winter Range designations or special orders.

“And they are even chipping away at that 40 per cent,” Petryshen said.

A provincial forester, in an email to Petryshen reviewed by The Narwhal, confirmed that an analysis showed 93 hectares have been logged in the Revelstoke/Shuswap ungulate winter range, which is supposed to be a no-harvest area.

“The intention of these caribou ungulate winter ranges were to protect caribou habitat. If we are failing to do that, it is very, very alarming,” said Petryshen, pointing out that 93 hectares amounts to 130 soccer fields of logging.

The email from the provincial forester states that one block was logged to salvage blowdown timber and others were either salvage logging, were approved before the regulations were put in place in 2009 or replacement habitat was provided.

Petryshen said an ongoing problem is the number of loopholes in regulations, such as approving roads through a protected area if there is no other feasible way to access timber.

Kerry Rouck, corporate forestry manager for the Gorman Group, whose subsidiary Downie Timber logged the block identified by Petryshen, said harvesting and the access road were approved before the caribou habitat order was approved in 2009 and, at that time, there was a provision for “work-in-progress” to go forward without major redesigns.

About 65 hectares of the 120 hectare block was harvested in 2020 because of an active spruce beetle infestation and the rest of the block will be left standing, so will contribute to caribou habitat, Rouck said.

Only small slivers of the logged area overlap protected habitat and other slivers outside the protected area were left standing, he said.

“The net effect is probably just a shift in the slivers, but no reduction in the overall [protected area,” he said.

The company is working closely with caribou management teams to develop a road rehabilitation plan “to make it less attractive for wolf travel” and the goal is to complete the work once reforestation has finished later this year or when funding becomes available through the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, Rouck said.

Tree planting along the road corridor will not have an impact for several years because of the snow load in the area, so other tactics, such as placing obstacles across the road and recontouring parts of the road, will be key, Rouck said.

Ideally, road rehabilitation should be incorporated into the stumpage system so it could be done on a wider, as-needed basis, rather than through proposals to the Habitat Conservation Trust Foundation, he said.

“When applied in concert with the other management tools — habitat protection, predator/prey management, maternity pens, recreation control etc. — we are optimistic that we will see the caribou population in the Revelstoke area continue to increase,” he said.

Splatsin First Nation, which formerly relied on caribou for everything from food and clothing to tools and snowshoes, has not hunted caribou for several generations because of decreasing population levels and shrinking habitat.

Former Chief Wayne Christian said the problem is bigger than logging encroachments into designated critical habitat and larger areas need to be protected from logging and other activities such as snowmobiling and ATV-riding.

“The problem is that the caribou don’t stay in one place, they move around and, in [government’s] strategy they have failed to recognize the mobility of the caribou and that the caribou is a keystone species and, once they disappear, the whole landscape will change,” Christian said.

Instead of a piecemeal approach, the whole area should be protected, he said.

“If you look at what has happened over the last 100 years it is because of how they have opened up alleged Crown land — our territory — to logging, to mining and recreational use. The caribou have been driven out. In fact their habitat has been destroyed so they can’t survive,” he said.

Caribou memories, hardwired into the creatures’ DNA, are of the land and how they move around, leaving a minimal footprint on the land, and, when the area is disturbed, they disappear, Christian said.

The keys to caribou survival are truly protecting large swathes of land, enforcing those protections and restricting access and truly deactivating logging roads, he said.

It is estimated fewer than 230 southern mountain caribou remain in Secwepemc Territory, which stretches from the Columbia River valley, along the Rocky Mountains, west to the Fraser River and south to the Arrow Lakes.

Current Splatsin Chief Doug Thomas did not return calls from The Narwhal.

While habitat is being cut down, the province recently extended its controversial wolf cull by five years, citing the need to protect dwindling herds from predators, which follow prey such as moose and deer along logging roads into caribou habitat.

Since 2015, when the wolf cull started, 1,429 wolves have been shot from helicopters and it is expected that between 200 and 300 wolves will be killed each year of the program.

While government says that, without predator reduction, caribou herds will continue to decline and die out, others say the cull is not necessary or useful.

Chris Johnson, who has spent 25 years studying caribou and is an ecology professor at the University of Northern British Columbia, said that, especially in the southern area, the most effective strategy — and the biggest bang for the buck — would be to shut down the relatively few roads that take predators to higher elevations that are the last bastions of mountain caribou.

“Don’t get me wrong, moose and wolves can walk through forests, but [roads] do act as predator highways and, when caribou cross those roads, they run a greater risk of running into one of those predators,” said Johnson, who previously sat on committees advising the federal government on caribou recovery.

Johnson said he has wildlife camera images of wolves following moose and their calves up the logging roads.

“The kicker is the caribou have to cross the road to go from one range to another, so, when they make those moves, they are in trouble. They run a lot of risk of running into a wolf or a bear or wolverine,” he said.

In the winter of 2019, the province of B.C. spent $2 million killing 463 wolves in the habitat of 10 endangered caribou herds — an average $4,300 per wolf. During this time 10 wolves were shot in the habitat of the Columbia North herd where the Ministry of Forests, Lands, Natural Resources Operations and Rural Development spent $100,000 — an average of $10,000 per wolf.

Mismanagement of forests has caused the caribou decline and serious conservation measures are needed, rather than wolf culls, according to Raincoast Conservation Foundation senior scientist Paul Paquet.

“This is wildlife management masquerading as conservation in a cynical effort to avoid doing what is clearly necessary — protect caribou from the ecological harm caused by people and industry,” said Paquet, who is a large carnivore expert.

Caribou depend on thick, old-growth forests to shield them from predators and provide the lichen they need to survive, but, over time, the logging industry has removed much of the old-growth and replaced it with younger trees and roads that provide convenient paths for wolves to access their prey, Paquet said.

“Caribou are now on a slow slide to extinction as victims of deadly incompetence and diminishing interest in environmental preservation,” he said.

The history of provincial efforts to protect mountain caribou stretches back to 2003, when the they were first listed as threatened under the Species At Risk Act. In 2005, a 14-member science team was put together to come up with recommendations. A draft recovery plan was released in 2006 and adopted the following year, with 10 special orders for caribou protection approved in 2009.

However, after the provincial government moved to protect caribou habitat in 2009, companies were compensated by being granted permission to log in nearby old-growth areas that were previously off-limits, Petryshen said.

“In all, the amendment made 7,049 hectares, or more than 8,000 soccer fields worth, of previously protected or constrained old and mature forest available for potential logging … That was so ridiculously absurd because caribou and old-growth forests are so connected,” Petryshen said.

A 2013 report by the Forest Practices Board, B.C.’s independent forestry watchdog, said the changes would result in less mature forest being retained, especially in lower elevations, and that logging those areas would fragment ecosystem connectivity and could make caribou recovery more difficult.

“It’s a very complex economic, social, environmental landscape that requires new thinking, all kinds of partnerships and everyone to be part of the solution,” said Peel, the strategic director with B.C.’s species at risk recovery branch.

Forest companies are in a challenging position as they balance caribou protection with providing jobs and ensuring profits for the company, he said.

“So it’s an ongoing conversation that requires a lot of deep thinking to find solutions,” said Peel, who has worked on caribou issues since 2008.

Maternal penning and predator control are seen as short-term measures, but many experts point to the need for stronger habitat protections for caribou province-wide. This is especially the case in areas like those near Revelstoke where caribou populations may have a chance at repopulating their historic ranges.

“It is a complicated area for companies to work in … there’s numerous resources and users out there,” Rouck said.

Johnson, from the University of Northern British Columbia, said there is ongoing discussion about which areas are core caribou range — consistently occupied by caribou — because the provincial government has not released core habitat maps.

Surrounding the core is the matrix of areas that need to be managed for other factors, such as logging and logging roads, but, again, the government has not released the maps, he said.

“I don’t know why not. … You don’t need to be a specialist in caribou to know this species needs habitat and that habitat change is the primary factor resulting in caribou population decline, but many would argue we haven’t gotten far enough yet to protect those habitats for that endangered species,” Johnson said.

“I’m not party to internal government conversations, but I suspect there are some discussions about the implications for timber supply in releasing and managing core caribou habitat,” he said.

A Forests Ministry communications spokesman told The Narwhal via email that some maps were included in a 2014 Caribou Recovery Strategy that, under the agreement with the federal government, is being updated along with the maps.

“This work is underway now and we expect to be engaging Indigenous Nations and the public this year,” he wrote.

Forest companies will also be part of that discussion and Rouck said the Gorman Group takes social responsibility and caribou protection seriously.

“It’s not all black and white. There are rules about how you behave on the land base and what you do and then there’s what’s acceptable and sometimes the rules don’t address the acceptability. You have to go above and beyond in some cases,” he said.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. On a warm September evening nearly 15...

Continue reading

Governments of the two provinces have eerily similar plans to give themselves new powers to...

Katzie First Nation wants BC Hydro to let more water into the Fraser region's Alouette...

Premier David Eby says new legislation won’t degrade environmental protections or Indigenous Rights. Critics warn...