What Carney’s win means for environment and climate issues in Canada

Mark Carney and the Liberals have won the 2025 election. Here’s what that means for...

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter.

A short walk down the beach from the marble-gilded interior of the Trump Hollywood luxury condos in Florida, a throng of suited executives and investors gathered in late February for the annual Bank of Montreal mining and critical minerals conference. The vibe was buzzy.

“You can feel that optimism in the air,” Josh Goldfarb, managing director of the metals and mining group at BMO Capital Markets, said in a podcast taped at the event.

After years of muted investment, the mining industry is seeing a resurgence, as demand soars for minerals deemed “critical” by governments for everything from weapons to renewable energy.

“Metals are the new oil,” John Steen, an associate professor and a distinguished scholar in global mining futures at the University of British Columbia, tells The Narwhal. “That’s the situation we’ve arrived at in 2025.”

U.S. President Donald Trump’s desire to annex Canada and acquire its critical minerals in the process is a “real thing,” according to former prime minister Justin Trudeau — and the U.S. has also set its sights on Ukraine’s largely untapped supply.

As B.C. responds to fast-changing geopolitics and the U.S.-Canada trade war, the province is wielding critical minerals as a power tool, promising to expedite mining projects to buffer against the economic shocks of U.S. tariffs, focusing on new trading partners now that the U.S. has gone AWOL. Amidst all the uncertainty, one thing is clear: much more mining is on the horizon for B.C.

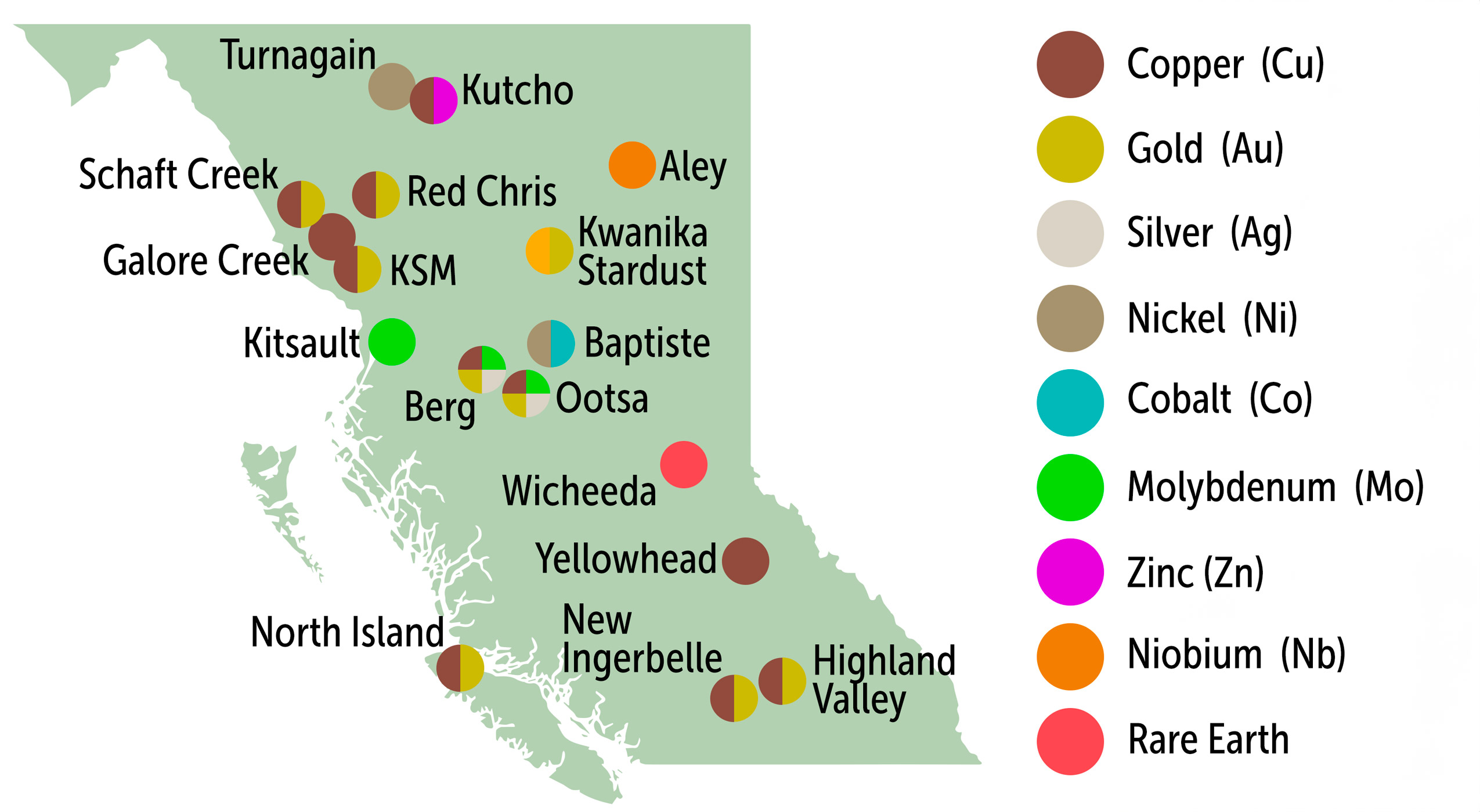

According to the Mining Association of BC, the province has 17 new critical mineral mining projects in the works, including for copper, nickel and molybdenum, which is used to make steel alloys. Seven projects will mine gold, which the federal government doesn’t include on its list of metals deemed “critical.”

As Trump angles to weaken the Canadian economy and gain access to Canada’s water and minerals, B.C. is using critical minerals as a climate-friendly political football of its own. But there’s no guarantee the province’s critical minerals will be used for the energy transition instead of for weapons manufacturing. And some observers are worried the B.C. government’s new plan to fast-track B.C. mining projects will hinder environmental scrutiny and the province’s commitment to uphold Indigenous Rights.

In February, a hard-hatted Premier David Eby stood in front of a ship filled with copper concentrate mined in B.C. and destined for Asia. Eby described the load of copper as “an example of the kind of work we’re going to expand.”

“There is unlimited potential,” he said. “We have what the world needs here.”

The next day, on Feb. 4, the B.C. government released a list of 18 energy and mining projects it will expedite, including four mines in various stages of development.

They include the expansion of two existing gold and copper mines, building a new gold and silver mine and expanding the Highland Valley Copper mine, Canada’s largest copper mine, southwest of Kamloops, B.C. Eby has also hinted the government will soon expedite more mining projects.

Eby’s fast-tracking announcement didn’t sit well with some First Nations, including Tahltan Nation, whose territory will house two of the fast-tracked mines. In a statement, the Tahltan said the province didn’t engage with the nation before announcing projects will be expedited.

“If you want certainty and you want it quickly, the only way you can achieve that is with free, prior, informed consent of the First Nations that are impacted,” Allen Edzerza, a Tahltan Elder and advisor on mining reform, said in an interview. “There’s no shortcuts in that regard.”

Edzerza is concerned B.C.’s expedited approach could have a negative impact on First Nations’ rights and the environment.

One mine slated for fast-tracking in Tahltan territory, the Red Chris Porphyry Copper-Gold project, was flagged in a report about B.C.’s highest-risk mines for tailings dam failures. The mine’s owners, Denver-based Newmont Corporation and Vancouver-based Imperial Metals, are proposing to switch to underground mining, which requires careful planning to avoid potential ground collapse.

On March 18, the government also announced the Gibraltar copper-molybdenum mine in south-central B.C. will not undergo an environmental assessment for its expansion plans, a decision opposed by Xatśūll Nation, whose territory faces lasting effects from the Mount Polley tailings dam failure in 2014.

And then there’s the question of how B.C.’s critical minerals will be used. On one hand, they’re vital for helping the world reduce dependence on fossil fuels — renewable energy technologies like wind and solar are voracious mineral consumers. The International Energy Agency estimates critical mineral production will need to quadruple by 2040 to keep global warming below 2 C.

But Thea Riofrancos, strategic co-director of the U.S.-based Climate and Community Institute think tank, says those demands aren’t set in stone. Riofrancos’ research found U.S. lithium demand could be reduced by up to 92 per cent by 2050, through actions that include using smaller electric vehicles, better battery recycling and reducing car dependency.

There’s absolutely no guarantee critical minerals — found in a vast array of products from iPhones to bombs — will be used for renewable energy projects that help the world reduce reliance on fossil fuels. “There’s a whole set of questions that are immediately pretty obvious when we start unpacking this term,” Riofrancos, who is also an associate professor of political science at Providence College in Rhode Island state, says in an interview. “Whose economic needs are being prioritized here?”

Riofrancos, whose research focuses on resource extraction, climate change, the energy transition and the global lithium sector, says the term critical minerals is being thrown around “without a lot of attention to what it means.” Under the term’s ubiquitous banner, goals of national security, economic growth and climate action tend to get jumbled together.

“There’s no questioning of what is critical for whom,” she says.

There’s nothing inherently “critical” about critical minerals; they’re a label governments use to identify mined products that dovetail with national interests.

“There’s a Venn diagram between ‘really need it’ and ‘could potentially be scarce,’ ” Bentley Allan, an assistant professor of political science and an affiliate of the Ralph O’Connor Sustainable Energy Institute at Johns Hopkins University, tells The Narwhal.

Canada lists 34 critical minerals, with a special emphasis on lithium, graphite, nickel, cobalt, copper and a universal category of 17 magnetic minerals known as “rare earth” elements. So far B.C. hasn’t created its own critical minerals list, but last year it produced an atlas documenting its mineral resources and the countries that want them.

Minerals deemed critical are perhaps best-known for their use in renewable energy. An average wind turbine, for example, requires an elephant’s weight in copper. Solar panels use minerals like cobalt, lithium and chromium, as do electric vehicles and their batteries.

But critical minerals are also used to make tech products like semiconductors, which are the building blocks of chips in iPhones and the “picks and shovels” of the artificial intelligence boom.

And then there are military uses; B.C. has significant inventories of minerals used to produce many tools of warfare. Molybdenum hardens armour, while tungsten creates weapons that can pierce through it. Cobalt can be used to strengthen jet engines. Germanium, a black and white metal, is used in infrared-detecting drones and night vision goggles.

The fast-tracked Highland Valley copper mine is already producing molybdenum, while Vancouver-based Happy Creek Minerals plans to mine tungsten in south-central B.C. Along with China, the province is one of the world’s few exporters of germanium, which it imports from Alaska and processes at Teck Resources’ refinery in Trail, B.C.

Thanks to B.C.’s geological position alongside shifting tectonic plates, many of B.C.’s critical mineral reserves bubbled up through the earth’s crust over time, forming deposits in places like the Golden Triangle in northwest B.C., mainly in Tahltan territory, where gold, silver, copper and molybdenum are abundant. B.C. is Canada’s largest supplier of copper, a critical mineral on the federal list. Of Canada’s 34 listed critical minerals, B.C. has significant potential to mine 14, according to the provincial government.

For companies that extract and process minerals, getting on Ottawa’s coveted “critical” list can be advantageous. Inclusion on the list provides access to Canada’s $1.5 billion fund that invests in infrastructure like highway expansions around mines. “There’s more money available if you’re on the critical minerals list,” Allan says. Last year, for example, mining advocates succeeded in getting Canada to add high-quality iron ore to the list, but attempts to add steelmaking coal did not succeed.

Although mining has long been part of B.C.’s history, like many other regions the province has grown increasingly reliant on products mined and processed elsewhere.

China’s ownership of the critical minerals supply chain has exploded — it extracts about 60 per cent of the world’s rare earth minerals and hosts 85 per cent of the factories required to turn them into usable products. Kristen Hopewell, a professor and director of the Liu Institute for Global Issues at the University of British Columbia, says China could decide to cut off that supply.

“There’s growing concern about the fact that China is so dominant,” Hopewell, the Canada Research Chair in Global Policy at UBC’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs, points out.

Concerns about critical minerals supplies in Western countries grew in the 2010s as Trump’s first administration created an early wave of protectionist laws. Former U.S. president Joe Biden continued the trend, imposing trade limits on U.S. computer chips, while China responded with its own tariffs. “This [was] ratcheting up in the background,” Allan explains. “There’s this tit for tat.”

At first, Canada and the U.S. buddied up, signing an agreement to help keep each other stocked. The two countries even made joint investments in a Northwest Territories mine producing the critical mineral bismuth, a rocket propellant, and a plant turning graphite into battery materials in Quebec.

As a supplier of 17 minerals the U.S. deems “critical,” Canada launched its critical minerals strategy in 2022, with a $3.8 billion investment in the sector. B.C. followed suit last year with its own critical minerals plan, including the establishment of a new critical minerals project advancement office and a commitment to expand the sector through investments in power infrastructure, training and subsidies, among others.

Those plans soured when Trump threatened 25 per cent tariffs on all Canadian exports after he returned to office in January, triggering fears of an economic recession. After two last-minute, one-month reprieves, some tariffs are still slated to take effect on April 2. “This is an existential threat for Canada,” Hopewell says. “The potential impacts are totally devastating.”

Yet it’s unclear if the B.C. government’s commitment to fast-track mines will get those projects off the ground any sooner. A study in FACETS journal found recent B.C. mines were delayed because of economic factors and commodity prices, not regulatory red tape.

But industry groups like the Mining Association of BC argue otherwise. “It takes too long to permit and authorize a mining project in B.C.,” the association’s president and chief executive officer Michael Goehring says in an email in response to questions from The Narwhal. The association said recent mine approvals took eight to 11 years to complete, and expediting projects supports “small, medium and Indigenous businesses and communities, workers and families throughout B.C.”

Modern mining is also not particularly labour-intensive, and companies tend to overstate job opportunities in their assessments — the same FACETS study found a group of B.C. mines employed roughly half the people they’d promised.

There’s also the question of whether Eby’s announcement will indeed herald sweeping changes. Many tools to speed up project approvals had already been introduced prior to the announcement, so it’s still unclear how B.C.’s new fast-track commitment will impact how mining projects are assessed. Three of the four mining projects Eby moved to the fast-track lane were already undergoing environmental assessments.

The Eskay Creek gold and silver mine, slated for Tahltan territory, is a new open-pit operation. Two other fast-tracked projects are existing mines seeking to expand: the Red Chris Porphyry copper and gold project wants to switch from an open-pit mine to underground caving — a method to help extract metal from deep underground that comes with added risks of dam failure, according to proceedings from the Eighth International Conference and Exhibition on Mass Mining.

The Highland Valley copper mine is also seeking an amendment to its environmental assessment certificate so it can expand. The mine’s owner, Teck Resources, is currently in a dispute resolution process with Stk’emlupsemc te Secwépemc Nation, which opposes the expansion, while other nations like the Kanaka Bar First Nation and the Lower Nicola Indian Band have consented.

The Mount Milligan copper and gold mine in Fort St. James, which rounds out the quartet of fast-tracked projects, has not yet announced any expansions or proposed amendments to its environmental assessment certificate. In an email, B.C.’s Ministry of Mining and Critical Minerals said it anticipates receiving applications for such changes “shortly.”

In B.C., major mining projects must go through an environmental assessment process and receive a government-issued certificate as well as permits. Typically, those permits wouldn’t be granted until the environmental assessment is complete. But B.C.’s new processes mean they’ll happen in tandem. “They both will go parallel, in other words,” Jagrup Brar, B.C.’s new minister of mining and critical minerals, says in an interview.

The province also introduced a single application process for both environmental assessment and permits. In its email, the ministry said this will help “reduce duplication.”

Brar says B.C. has launched a concierge service within its new critical minerals project advancement office for early-stage mining projects “with a significant potential to boost the economy.” So far, the office’s sole project is the Baptiste Nickel project, a mine proposed by FPX Nickel in Tl’azt’en Nation’s territory in north central B.C. The nation terminated its memorandum of understanding with the company in 2023, stating it does not consent to the company’s activities.

The mining ministry said it has recently convened a group of deputy ministers involved in mining approvals to “clear obstacles” and move projects forward faster and will put a “greater focus” on its new processes of pairing up permit reviews and environmental assessments.

Meanwhile, the ministry’s recent service plan hints more overarching changes are in the works — among them, a commitment to set fixed timelines for mine approvals and “dramatically reduced” permit wait times.

B.C.’s new focus on fast-tracking mines leaves some observers asking if the plan will hinder environmental scrutiny or B.C.’s commitment to uphold Indigenous Rights.

“My simple answer is no,” Brar says. “Our focus is streamlining.”

But it’s difficult to square how the government will meet the fixed deadlines it has promised to implement with only tweaks to existing processes.

Nasuʔkin (Chief Councillor) Cheryl Casimer, with the First Nations Summit political executive, worries Eby’s focus on fast-tracking speaks to a culture of jamming projects through.

“Whenever I hear the word fast-tracking, it worries me,” Casimer, a citizen of the Ktunaxa First Nation, tells The Narwhal. “That means that you go ahead and you do it no matter what.”

Casimer is also wary that fast-tracked mining will steamroll over Indigenous Rights.

B.C. has committed to changing laws to align with the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act, but it still allows companies to explore for minerals and apply for environmental assessments without the consent of First Nations. Companies aren’t required to include First Nations in the early stages of project planning.

“There’s a lot of things that could be done right at the outset to make sure that there’s that level of certainty,” Casimer says.

Casimer’s territory in southeast B.C. has suffered the aftermath of mining gone wrong. Selenium pollution from coal mines in the Elk Valley has leached into the waterways and the eggs of female fish, sometimes deforming their spines and heads or killing them before they hatch.

Acid rock drainage occurs when blasted rock is exposed to oxygen and water, causing it to leach heavy metals like selenium. It’s not limited to coal mining — mining for critical minerals can trigger acid rock drainage, too. Both waste rock and tailings — the ground-up bits of rock left over from mineral extraction — can leach into waterways if left untreated.

Teck Resources, until recently the owner of the Elk Valley coal mines, was fined for its pollution, but Casimer says she has seen little change. “All they do is pay their fine and carry on.”

Nadja Kunz, an associate professor at the University of British Columbia who is the Canada Research Chair in Mine Water Management and Stewardship, is also concerned by fast-tracking commitments.

Kunz says companies often provide subpar information on issues like water quality during the environmental assessment process, and mining’s long-term risks to water make it critical to get the details right.

“It is really important that we don’t encourage government to shortcut on this, because the legacies from mining are felt so widely in Canada already.”

“There are plenty of mines in B.C. or Canada where we’re going to have to be treating that water forever,” Kunz, who is jointly appointed across UBC’s School of Public Policy and Global Affairs and the Norman B. Keevil Institute of Mining Engineering, points out.

Tailings pond stability presents another major risk. Just over a decade ago, the Mount Polley copper and gold mine’s tailings pond breached, spilling roughly 10,000 Olympic swimming pools worth of toxic tailings into Polley Lake in B.C.’s Interior.

B.C.’s auditor general prescribed a list of actions to avoid similar disasters, including using the best available technologies to reduce or eliminate water in tailings. But B.C. still doesn’t require companies to use those technologies, which are more expensive to implement.

“You’re still getting economics as the main driver,” Nikki Skuce, a director of the non-profit Northern Confluence and co-chair of the group BC Mining Law Reform, says in an interview.

For new mines, those waste rock piles and tailing ponds are likely to be even bigger, compounding the problem, Skuce says. “We’ve mined all the easy stuff first.” As sites with the highest concentration of minerals get mined out, she says companies increasingly target sites where minerals are more spread out, meaning there will be more waste material.

“The waste dams in British Columbia are bigger and taller, and therefore there’s more risk,” Skuce says.

Casimer says it’s important to have a conversation about the needs and benefits of critical minerals.

“If somebody needs critical minerals, then yes, let’s take a look at what that means,” she says.

“But we need to be decision-makers at the table.”

Updated on March 24, 2025, at 4:57 p.m. PT. This story was updated to say Canada is a supplier of 17 minerals the U.S. deems critical, as per an email from Natural Resources Canada that was received following publication.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Mark Carney and the Liberals have won the 2025 election. Here’s what that means for...

An invasive pest threatens the survival of black ash trees — and the Mohawk art...

Xatśūll First Nation is challenging B.C.’s approval of Mount Polley mine’s tailings dam raising. Indigenous...