Water is precious — and precarious — on First Nations reserves like this one

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

Doug Smith, deputy incident commander for the Donnie Creek wildfire in B.C., had sobering news to share June 11 on a daily call with oil and gas companies and other critical infrastructure operators. The out-of-control fire had amassed so much energy it was hurling pinecones and small branches into the air and tossing the flaming debris outside its perimeter to gain ground like an advancing army.

“We are seeing a solid fire front, where you have fire from the ground to the treetops and flames above the treetops, perhaps 50, 60 feet or higher,” Smith explained. The height of the fire, combined with its “spawning” activity, indicated significant spread, threatening properties, the Alaska Highway, the CN railway and fracking operations in northeast B.C.

Usually wildfires calm down at night. But unseasonably hot temperatures and low humidity drove the Donnie Creek wildfire to rage on that night, sending thick and gritty smoke far and wide. By Wednesday, the fire, abetted by high winds, had engulfed an area approaching the size of Prince Edward Island. By June 18, it became the largest ever wildfire recorded in the province.

Even with 188 firefighters, 28 pieces of heavy equipment and 11 helicopters, Smith said there is little hope of stopping the lightning-sparked blaze from spreading over the next few months, given its expanding 300-kilometre perimetre. “We really need to expect that the fire is going to persist in the area indefinitely,” he told The Narwhal from the fire’s command centre in trailers at an oil and gas camp at Mile 147 on the Alaska Highway, where he and other supervisors are working from seven in the morning until nine at night.

Most of the fire can’t be contained, Smith said, so the priority is to protect people, communities and critical infrastructure — chiefly the railway, the highway and fracking operations.

Fracking is the process of injecting chemicals and huge quantities of water deep into the earth, under high pressure, to fracture and break open shale rock so it releases trapped gas.

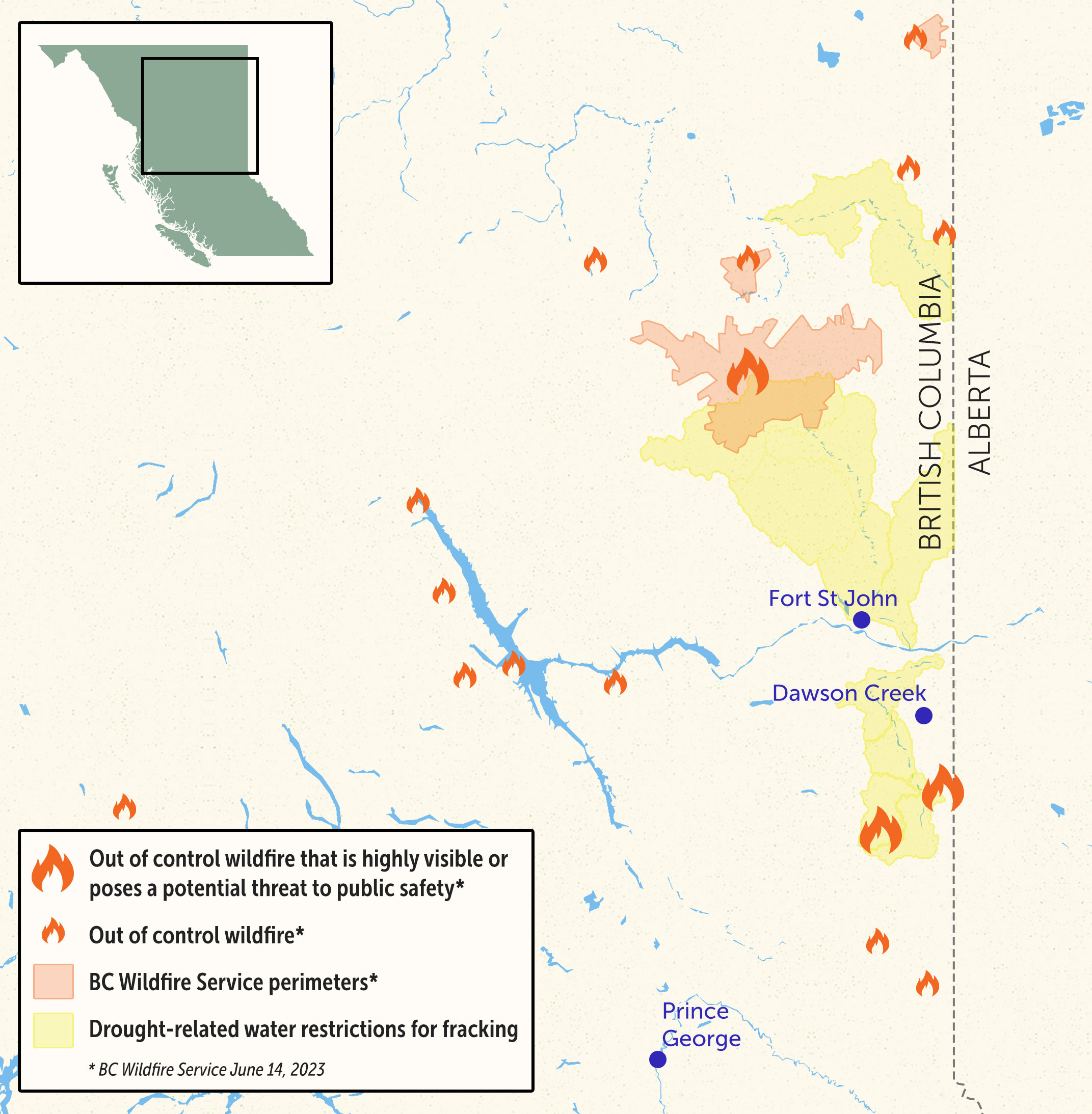

The area burned by the Donnie Creek wildfire over the past four weeks, roughly halfway between Fort Nelson and Fort St. John, sits in the north part of the Montney basin, a vast hydrocarbon-rich region. Tens of thousands of fracking wells crisscross the Montney, with plans to drill tens of thousands more to supply LNG Canada, the country’s first liquefied natural gas (LNG) export project, through the Coastal GasLink pipeline.

The fast-moving fire in B.C.’s Peace Region raises some troublesome questions: what happens when fire meets fracking? Are there human health concerns? And what impact could increasingly intense and frequent wildfires expected with climate change — and drought that restricts access to water for fracking operations — have on the BC NDP government’s gambit to promote LNG?

Chemicals used to frack wells are highly toxic, according to Tim Takaro, a physician-scientist who studies the links between exposure to toxicants and disease. They vary from operation to operation but include polychlorinated compounds and petroleum-based compounds with polyaromatic hydrocarbons — a class of chemicals associated with lung, skin and bladder cancers from occupational exposure, in addition to exacerbating asthma and increasing rates of obstructive lung and cardiovascular diseases.

Takaro, professor emeritus and former associate dean for research in Simon Fraser University’s health sciences faculty, is trying to determine what happens if a wildfire burns through a fracking operation. Fracking releases methane mixed with other polyaromatic hydrocarbons and other toxicants like mercury, sulfur dioxide and hydrogen sulfide, he pointed out. “Burning that is not a good idea. Many of these chemicals are carcinogenic. Some of them are also reproductive toxicants.”

“Depending on the stage of the fracking, there will be gas on site. There will be fracking materials stored in tanks. And there will be a network of piping and the well itself. So there’s plenty of material there that you would not want to have released into the atmosphere.”

Burning produces particulate matter containing its own complex mix of toxicants, which can include polyaromatic hydrocarbons and heavy metals, as well as nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide and the particles themselves, which are harmful. “This is a toxic mix, concentrated in a generally rural area, surrounded by forests,” Takaro said. “It’s not hard to conceive of an out of control wildfire ripping through one of these facilities.”

The Donnie Creek wildfire has forced 18 fracking operators to take some form of protective action, including shutting down sites and evacuating personnel, according to the BC Energy Regulator (formerly the BC Oil and Gas Commission). More than 60 energy companies in B.C. have reported impacts from wildfires this season, such as having to secure their sites by ensuring pads are clean and removing vegetation and debris to prevent fires from finding a new source of fuel. The fracking disruptions come as Environment and Climate Change Canada warns higher-than-normal wildfire activity could continue across most of the country this year, which has already produced the worst wildfire season this century.

The regulator said structure protection units, deployed by the fire’s command centre, are carrying out “significant work” to secure fracking sites in the path of the Donnie Creek wildfire, noting flammable products like gas can be removed from sites.

“When safe to do so, products can be moved out of proximity of a fire,” the industry-funded regulator said in an emailed response to questions, after declining a request for an interview. Flammable products left on site are reported, the regulator said, and the information is shared with responders so they can decide on the “most appropriate” firefighting actions.

The regulator didn’t respond to questions asking what types of flammable products were removed from fracking sites in and around the Donnie Creek fire and what types of products were left behind. “Ensuring sites have been made as safe as possible and risks minimized is, and will remain, the priority.” It said only one operator of an inactive fracking site has reported damage from a wildfire, noting other operators have not yet been able to access sites to assess any damage.

Contaminated water from fracking is stored in waste pits, which can contain heavy metals, carcinogens and naturally occurring radioactive materials. The regulator said the pits — known as fracking ponds — are not a fire concern. “We would expect nothing to happen to these contaminants. The volume of water inside provides natural protection should any fire come in close proximity.”

Takaro isn’t so sure. He asked the government if fire smoke is monitored for toxicants and if emissions are factored into evacuation orders. “And the answer was no, that generally it’s based on wildfire behavior and weather patterns, not based on the human health effects of the emissions.”

“So we don’t know what health effects are when a wildfire sweeps through a fracking facility,” he said. “But one thing we do know is that fracking increases the risk of wildfires. You increase [carbon] emissions, you increase temperatures, you increase drying, you increase the number of trees that are dying because they don’t have enough water. And you have more fuel for these fires that are becoming more and more frequent and more and more intense … Fracking operations make this whole cycle worse. And that is the connection [the] government refuses to make.”

B.C.’s early and fierce fire season coincides with another threat to the province’s heavily subsidized LNG industry, championed by the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers and the Alberta government’s energy war room.

Widespread drought in the northeast, also linked to climate change, is restricting access to water for fracking operations. Canada’s main oil and gas industry lobby group, the Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, estimates between five million and 30 million litres of water are used for each fracking well.

If water is not available locally, it must be trucked in. Small fracking jobs can require hundreds of water tanker trips, while larger jobs can generate more than a thousand trips.

On May 25, the BC Energy Regulator issued its earliest-ever water diversion directive, instructing oil and gas operators to immediately suspend approved water use in rivers, lakes and streams in two watersheds in the province’s northeast. “Drought conditions and streamflow response to drought is occurring much earlier than in previous years,” the regulator said in the directive, noting that recent rainfall has not been sufficient to alleviate concerns about low flows in the river systems.

Such directives have become commonplace in the late summer and early fall due to multi-year drought in the Peace region. In its email, the regulator said the May 25 directive impacts four operators and four withdrawal sites, including on the Kiskatinaw River, a region where another large wildfire burns, one of 84 active wildfires in the province. Drought conditions are being monitored and additional withdrawal suspensions may be rolled out in the coming weeks, the regulator said.

Oil and gas industry analysts are keeping a close watch on the volatile fire and drought situations in B.C., mindful that Alberta’s gas production has slumped due to wildfires.

Thomas Liles, vice president of upstream research for Rystad Energy, an independent research and business intelligence company, said B.C. gas production could be affected by wildfires but it’s too early to say with certainty what the impact will be. “If you get a repeat of the forest fires that we saw in 2016, in Fort McMurray, that shut down a large number of oilsands projects, then you would start to get quite a few ripple effects.”

Clark Williams-Derry, an energy finance analyst for the Institute of Energy Economics and Financial Analysis, pointed to wildfires and drought as material risks for fracking operations in B.C.

Drought will increase fracking costs because it requires more water to be trucked in over longer distances, Williams-Derry said in an emailed response to questions. “This adds additional cost pressure to an industry that is already having to adjust to a changing and challenging regulatory environment.”

He said the increasingly troubling effects of climate change add to the risk profile for a region where industry faces other serious challenges, including a negotiated settlement with Blueberry River First Nation that will require the fracking industry to greatly reduce its physical footprint. The nation was not available for comment on the Donnie Creek wildfire.

In an emailed response to a request for an interview, a media spokesperson for LNG Canada said the consortium is not involved with upstream activities such as the supply of natural gas, suggesting The Narwhal contact natural gas producers for comment.

The Narwhal contacted Malaysian state-owned Petronas, one of the biggest players in the north Montney region, but did not receive an answer, aside from an acknowledgement the email was received. Petronas owns 25 per cent of the LNG Canada project, a consortium of five multinational oil and gas companies that are receiving at least $5.34 billion in government subsidies.

As wildfires erupt with more frequency and intensity due to climate change, Takaro urged the provincial government to examine the impact on fracking operations, with an eye to human health. “I think all of this bears scrutiny,” he said. “And very little scrutiny is happening in this industry.”

Updated on June 16, 2023, 4:29 p.m. PT: A previous version of this story listed Tim Takaro as the associate dean for research in Simon Fraser University’s health sciences faculty. Takaro is the former associate dean for research, a professor emeritus and an active member of Simon Fraser University’s faculty of health sciences planetary health research group.

Updated on June 19, 2023, 10:54 a.m. PT: This article was updated to reflect that the Donnie Creek wildfire had become the province’s largest ever recorded wildfire.

Get the inside scoop on The Narwhal’s environment and climate reporting by signing up for our free newsletter. When I visited my reserve, Moose Factory,...

Continue reading

Boil-water advisories in Moose Factory, Ont., are frequent, expensive and ongoing — but not ‘long-term’...

On the election trail, Canada's federal leaders are pushing military and industry in the North....

President Trump’s threats towards Canada carry great risks to Americans as well, and to the...