Ontario’s public service heads back to the office, meaning more traffic and emissions

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

The small Rocky Mountain city of Fernie, B.C., is on the hunt for a new backup drinking water supply after selenium levels exceeded provincial water quality guidelines in tests of its secondary water source earlier this year.

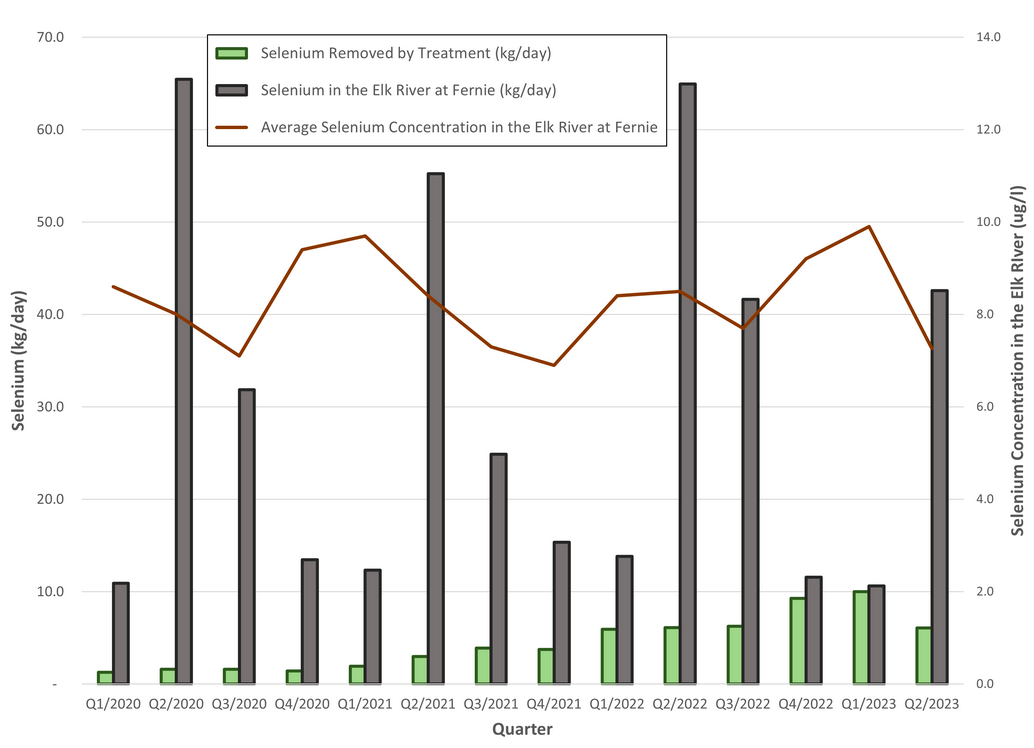

For decades, selenium has leached into local waterways from piles of leftover waste rock at coal mines in the Elk Valley, owned by Canadian mining giant Teck Resources. The company has invested more than $1.4 billion in water treatment and other measures to reduce the pollution. While it says its efforts are making a difference, selenium, a naturally occurring chemical element, continues to course throughout the watershed.

After recording selenium exceedances in its secondary drinking water source in April, the city announced on Dec. 7 it would begin drilling test wells this month as part of a search for a new backup water source.

The city said testing of the main drinking water source in Fairy Creek did not detect what it described as “selenium concentrations of concern.”

In an interview, Fernie Mayor Nic Milligan said he doesn’t have any concerns about the city’s drinking water supply at this point and commended the community’s water operators for their “cautious and careful” management of the drinking water system.

What he wants to avoid, he said, is a scenario where the city is unable to provide safe drinking water in the future. “Out of an abundance of caution, now is the time to investigate alternative backup sources,” Milligan said.

Fernie relies on water from the backup wells during periods of high turbidity in Fairy Creek when the water becomes cloudy with suspended particles. This is especially an issue during the spring melt and has led to boil water advisories in the past.

Randal Macnair, the Elk Valley conservation co-ordinator with the Kootenay-based organization Wildsight, worries elevated selenium levels could mean a return to more regular boil water advisories if, during times of high turbidity in Fairy Creek, the city can’t draw from its backup supply.

“It’s an inconvenience for most and it’s a legitimate health concern for many,” Macnair said of the boil water advisories.

The backup wells — which alongside supporting infrastructure cost $5.45 million to build — began operating in 2018. They are located at James White Park near the Elk River, where selenium levels have risen as coal mining in the region expanded.

According to the city, the river influences the groundwater source at James White Park and has at times caused selenium concentrations to exceed B.C. water quality guidelines.

“It’s a frustration, ultimately, but we have a plan and we’re working on that plan,” Milligan said.

In a statement to The Narwhal, Teck spokesperson Chris Stannell said “Teck and the City of Fernie are both working to monitor water quality in municipal wells and Teck is providing funding and technical support to identify a new backup water source.”

Selenium is an essential mineral for the body in small quantities and plays an important role, for instance, in regulating thyroid hormones, according to Health Canada. It can be found in food, in soil, in water and in the supplement aisle of your local pharmacy.

Exposure to high concentrations of selenium over a long period of time, however, can lead to a concerning health condition called selenosis, Fatemeh Sabet, a medical health officer with the Interior Health Authority, explained in an interview. Symptoms can include fatigue, hair and nail loss, weakness and dizziness.

According to Sabet, selenium concentrations detected in water from the James White Park wells this year ranged from three parts per billion to 12 parts per billion, at times exceeding B.C.’s guideline of 10 parts per billion.

Sabet noted that limit is “very cautious” and is lower than Health Canada’s guideline for selenium in drinking water, which is 50 parts per billion.

The province has taken a more precautionary approach because people in B.C. can be exposed to more selenium through their food, due to higher concentrations in the soil in some regions, including the Elk Valley, she explained.

But if selenium concentrations are below 10 parts per billion, “we are confident that people are accessing safe sources of water in terms of exposure to selenium,” Sabet said.

The city is continuing to use the James White Park wells when needed, but only when selenium concentrations are below B.C.’s guidelines.

Selenium levels are closely monitored, Milligan said, which means the city can react quickly to prevent water with higher concentrations from getting into the system.

According to a spokesperson for the city, testing completed in 2012 — before the James White Park wells were constructed — detected selenium levels of 5.2 parts per billion and 5.4 parts per billion.

Macnair, who was on city council at the time, said the understanding at that point was that there wouldn’t be any issues with selenium at that site.

Over the last several years, Fernie has turned to the James White Park wells to avoid boil water advisories during periods of high turbidity in Fairy Creek or to supplement water supplies when the creek is running low. In 2021, the backup wells supplied approximately 23 per cent of the community’s drinking water and 13 per cent in 2022, according to the city’s annual drinking water reports.

But in April 2023, when turbidity levels in Fairy Creek crept upwards, Fernie ran into trouble with its backup source. First, there was a mechanical issue with the James White Park wells, which meant the city had to draw from Fairy Creek despite the poor water quality. Officials advised residents to boil water before drinking it or using it to wash fruit and vegetables.

A few days later, water quality in Fairy Creek had somewhat improved, and though the city said health risks were minimal, it still urged children, the elderly and anyone with weak immune systems to boil their water before drinking it. By this point the mechanical issues with the backup wells had been resolved, but the wells still couldn’t be used. Testing showed selenium concentrations were too high, the city said in a public notice at the time.

Macnair said Wildsight asked the city to provide the complete set of selenium testing data but the city has not released that information. The Narwhal also asked the city for testing data from the last year and was provided the most recent annual water quality report and the highest selenium concentration detected in the wells — 12.2 parts per billion.

“This is a sensitive and really critical issue,” Macnair said. “It requires full transparency.”

Fernie isn’t the first community to run into problems with selenium in its groundwater. Just a few years ago, Sparwood, a municipality about 30 kilometres northeast of Fernie, drilled a new drinking water well to replace one where selenium concentrations were at times higher than B.C.’s guidelines. Several private wells have also been affected.

There are also significant concerns about the threat selenium poses to fish and other aquatic life.

Selenium levels in the Fording and Elk rivers are consistently higher than what the B.C. government considers to be protective of aquatic life and are a particular concern for at-risk fish. In fish, too much selenium can impede reproduction and cause deformities such as curved spines, misshapen skulls and abnormal gills.

According to the Elk River Alliance, a community-based charity that monitors water quality in the Elk River, selenium concentrations in the river around Fernie range from about five parts per billion to 15 parts per billion. That’s considerably higher than natural levels — around 0.4 parts per billion — detected in tributary streams not affected by mining, the group says. It’s also above the two-part-per-billion guideline the B.C. government considers protective of aquatic life.

According to Teck, the company’s water treatment facilities remove between 95 and 99 per cent of selenium from the water they treat. Teck is continuing to increase treatment capacity, but does not currently have capacity to treat all of the water contaminated by its mines.

In the meantime, Teck monitors drinking water in both municipal and private wells in the Elk Valley and in some cases has provided bottled water when selenium contamination has exceeded water quality guidelines.

In Fernie, alongside water monitoring, the company is investing in additional water treatment to address turbidity issues at Fairy Creek and providing funding and technical support to assist in finding a new backup source of drinking water.

Teck has “come to the table and they are being, in my mind, very responsible in terms of recognizing their influence on the watershed and working with communities and private well owners to ensure that they have safe drinking water,” Milligan said.

Asked whether the company will cover the costs of the replacement wells, the mayor said, “there will be an ongoing conversation about who’s responsible for the cost here.”

But it could be several years before Fernie has a new, reliable secondary source of drinking water.

The city is now drilling test wells on parkland near Lizard Creek. In the spring, flow and water quality testing will be done to assess the viability of the wells as a new secondary water source.

Milligan said if the tests show it’s a viable source of drinking water there will be a robust environmental assessment. And if the risks to Lizard Creek are too high, Milligan said he expects the city would consider another site for the wells.

“That is a vitally important trout spawning stream,” he said. “I have no interest in impacting Lizard Creek through this process.”

Enbridge Gas will face Waterloo Region in a hearing before the Ontario Energy Board to renew an agreement that would allow the company to continue...

Continue reading

For 15 years and counting, my commute from Mississauga to Toronto has been mired by...

For our last weekly newsletter of the year, we wanted to share some highlights from...

The fossil fuel giant says its agreement to build pipelines without paying for the right...