In Tlingit territory, the fight to protect herring is complicated

An excerpt from “We Survived The Night” by Julian Brave NoiseCat

The composition of the forest shifts in sometimes subtle ways between the shores of Kootenay Lake and the mountaintops at the edge of the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy.

Among a diverse array are species of fir and hemlock, spruce and larch. Cedar concentrate in the cool shadow of the creek beds. And in the upper elevation forests, the smell is “just invigorating,” long-time Argenta resident Gary Diers said, as he described the local landscape.

“The forest here is endlessly interesting,” he said.

On one of his favourite hikes the trees give way to the meadows and rocky outcrops of the subalpine and a small heart-shaped lake surrounded by peaks.

“You’ll always see grizzly bear activity there,” he said, “it’s one of those very good grizzly bear habitats.”

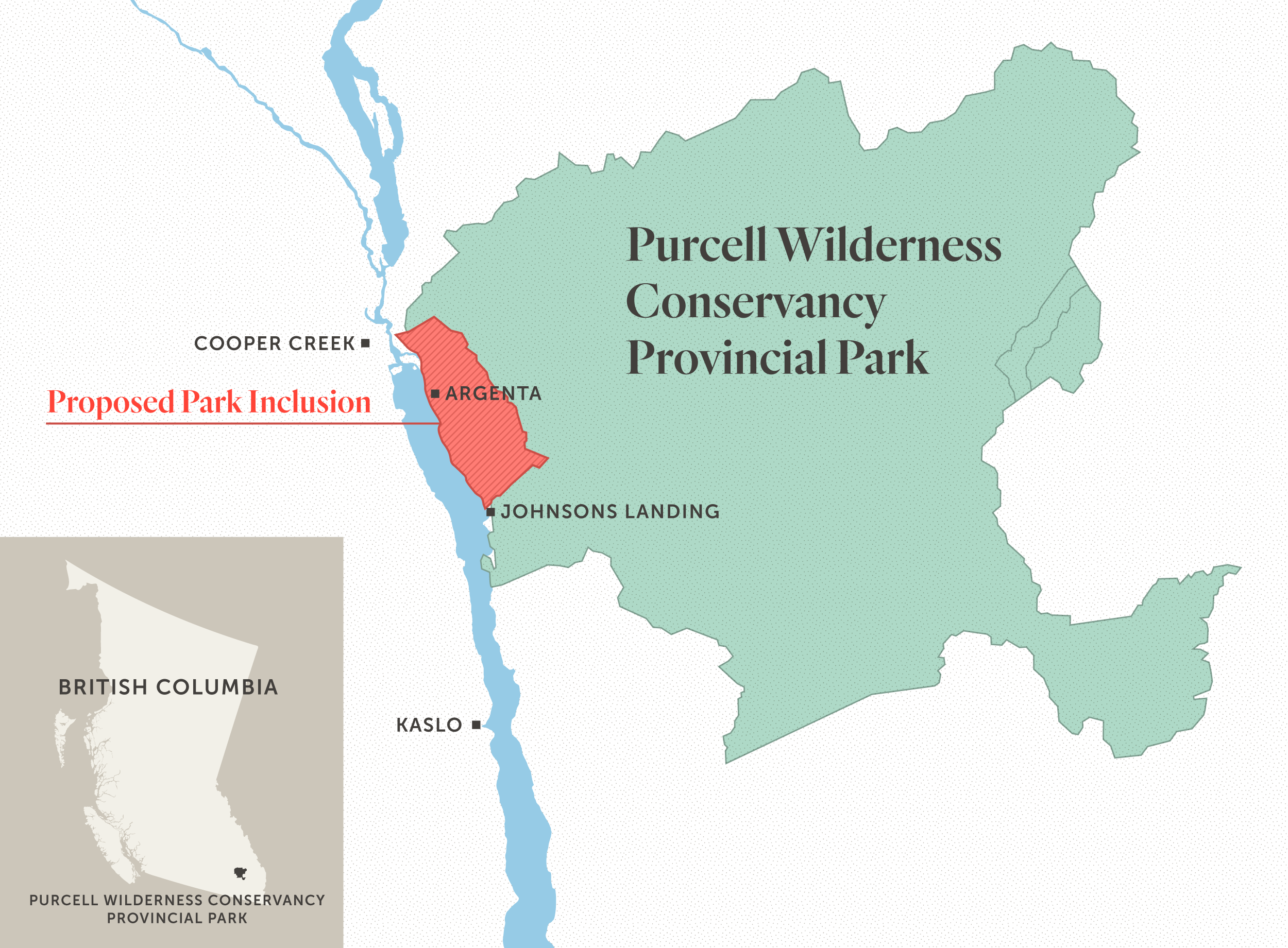

In the latest chapter of a decades-long effort to protect various swaths of this forest, Diers and a group of Argenta-area residents operating under the banner of Mt. Willet Wilderness Forever are calling for the mountainside between their small community and Johnsons Landing, about 10 kilometres to the south, to be included in the provincial park.

“When you consider that the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face is surrounded on three sides already by the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy it’s kind of one of those no-brainers,” he said.

The challenge lies in the interests competing for the trees that stretch across this mountainside, valuable as part of an intact forest ecosystem, for recreation — and as standing timber resources. Against the backdrop of a changing climate and the looming threat of destructive wildfires some see the way forward in a compromise between an industry that wants access to timber and conservationists who want complete protection for the area.

Cooper Creek Cedar, a company based in Salmo, B.C., holds a forest licence that allows it to log between Argenta and Johnsons Landing, among other areas. The B.C. government recently issued the company a permit to cut in six cutblocks on this mountainside in an area between Salisbury Creek and Bulmer Creek.

Bill Kestell, Cooper Creek’s woodlands manager, said the company has gone beyond regulatory requirements to address the community’s concerns by working with experts to study the potential impacts on wildlife and terrain stability in the Salisbury to Bulmer area and has adapted their logging plans in response.

Both Cooper Creek Cedar and area residents have invested “considerable hours” in discussions about the company’s plans and community concerns.

“We’re at different ends of the spectrum but we’ve … had very productive engagement,” Kestell said.

While Cooper Creek Cedar doesn’t support the proposal to include the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face in the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy, the decision ultimately falls to the provincial government.

And, at this point, the government is not considering protecting the area, Tyler Hooper, a spokesperson for the ministry of Forest, Lands, Natural Resource Operations and Rural Development, said in a statement to The Narwhal.

Local efforts to protect the forests that surround Argenta and Johnsons Landing date back decades. Historian Jenny Clayton’s 2011 article in B.C. Studies, for instance, credits their efforts in the late ’60s and early ’70s to prevent logging in the Hamill Creek area just north of Argenta as being “the catalyst of a larger wilderness preservation project.”

It was in the wake of that broader effort by conservationists from across the region and even further afield that Hamill Creek was ultimately protected as part of the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy. The park was created in 1974 by the NDP government despite concerns from the forestry industry that a large protected area in the Purcell Mountains would threaten workers’ livelihoods, according to the article.

The provincial park was expanded in 1995 as part of the West Kootenay land-use planning process and today protects more than 200,000 hectares of mountainous terrain. According to B.C. Parks, it is “the only intact ecosystem in southeastern B.C.”

But roughly 6,200 hectares of mountainside between Argenta and Johnsons Landing was left outside the bounds of the conservancy.

“Many trade-offs were made when land use decisions were made in the 1990s,” Hooper said.

More than 396,000 hectares of land across the Kootenays was protected through that process and the area of Purcell Wilderness Conservancy itself increased by more than half.

“The Argenta-Johnsons Landing Face, while containing values that complement the adjacent park was identified and assigned for mixed resource use and development in the earlier Kootenay Boundary Land Use Plan — with an acknowledgement that the area contains significant natural values,” he said.

Hooper added that a government regulation has classified most of the mountainside in question for “retention or partial retention” meaning that there are limits on how logging can be done and how many trees can be cut within certain areas.

“Cutblocks must be smaller in size and natural in appearance,” he explained.

Forestry has long been an important industry for B.C.’s economy. In 2019 it accounted for 51,800 direct jobs, contributed $5.9 billion to provincial GDP and made up 27 per cent of provincial export value, according to the government’s economic state of the forest sector report.

In the Kootenays, a 2021 Council of Forest Industries report that relied on 2019 data estimated the sector supported more than 4,800 direct, indirect, and induced jobs — roughly seven per cent of jobs across the region.

But tensions are spiking in some places across the province over concerns about the environmental consequences of logging in old-growth forests and other sensitive ecosystems.

Aimee Watson, the Regional District of Central Kootenay director who represents the area that includes Argenta and Johnsons Landing, agrees forestry is “a significant component” of the regional economy, but says “forests as a whole have been highly undervalued for everything else they offer us.”

Watson said she supports Mt. Willet Wilderness Forever’s calls for the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face to be included as part of the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy.

“The challenge for me as an elected official is it’s really easy to hear that statement and for everybody in the forest industry to equate that as being opposed to forestry,” she said.

But a broader conversation about the future of forest management is needed, she said.

“If we just stopped forestry, we would devastate this province, that’s the truth. So how do we get it right?” she said. “Our economic values need to change.”

There are a number of processes underway that may offer forums to interrogate those larger issues, including a review by the chief forester of how much timber is allowed to be cut each year in the Kootenay Lake Timber Supply Area.

At the same time, Hooper said the province is considering legislative changes that could allow for different approaches to landscape planning.

As for Mt. Willet Wilderness Forever’s more immediate concerns for the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face, Watson said Cooper Creek has gone “above and beyond” what the company is required to do, but the forests around remote communities should be managed for ecological resilience, something she said isn’t a primary mandate for forest tenure holders.

The Narwhal also requested an interview with Nelson-Creston NDP MLA Brittny Anderson, whose riding includes Argenta, through her constituency office. A spokesperson for the political party responded to say Anderson was not available.

For Carolyn Schramm, who has called Argenta home for some 50 years, it was “the beauty of the area,” that initially drew her to try and protect the mountainside.

“This area really contributes to the spirit and well-being of the residents who choose to live here and the people who choose to recreate here,” she said.

There are no paved roads in Argenta or Johnsons Landing, no traffic lights. In Argenta, the larger of the two small communities, the downtown consists of a post office and a community hall that hosts everything from funerals to weddings.

“We’re all rural. We’re a forest community,” said Schramm, who is being awarded the Suzy Hamilton Legacy Award, which recognizes the environmental activism of a self-identified woman in the West Kootenays.

“My concern is that the Argenta-Johnsons Landing face will really be devastated by logging and that it will create enormous damage to the wildlife habitat, the biodiversity and the ecosystem,” she said.

Logging in the Salisbury to Bulmer Creek area is just the beginning of Cooper Creek Cedar’s planned harvesting on this mountainside. The company is also developing plans to log in the Argenta Creek watershed, which would be closer to the community.

That’s “certainly not acceptable to many residents here,” Schramm said.

Mt. Willet Wilderness Forever’s efforts have gained support from a number of larger environmental organizations, including the Yellowstone to Yukon Conservation Initiative (Y2Y), which aims to connect large stretches of protected areas.

“There are high … ecological, social and economic values and a very high percentage of the community that lives there is in favour of those protections,” Candace Batycki, Y2Y’s B.C. and Yukon program director, said in an interview.

“The bigger context is the unsustainability of logging at all at this point. The easy places to log are gone and the places that are left have higher impacts,” she said.

Protecting the entire stretch of mountainside would mean adding more than five kilometres of lakeshore as well as low- and mid-elevation forest to the park, Diers explained.

The forest, some of which is old growth, supports grizzly bears, deer, mountain goats, wolverines and other wildlife. There have been signs of mountain caribou — which are at-risk of extinction in B.C. — in the area and great blue heron are known to roost during the winter in the forests south of Argenta, according to a wildlife biologist’s report for Cooper Creek Cedar.

In April, Diers and photographer Louis Bockner hiked up the mountainside to search for signs of caribou in the snow between the trees. While they didn’t find any tracks or scat, “there was lichen everywhere,” Diers said. “The lichen on the trees is what the caribou eat exclusively in the winter.”

The area also serves as part of an important wildlife travel corridor connecting the Purcell Wilderness Conservancy with Goat Range Provincial Park in the Selkirk Mountains on the other side of Kootenay Lake.

Michael Proctor, an independent research scientist based in Kaslo, has spent years studying grizzly bears in the Selkirk and Purcell mountain ranges.

“This area jumps out at you for sort of an obvious reason,” Proctor said. “It’s a pinch point in the ecosystem” and one of the few areas where wildlife can pass between Kootenay Lake to the south and Duncan Lake to the north to reach protected habitat on either side of the lakes.

There tend to be good huckleberry patches in open areas of the upper elevation forest in the mountains around Kootenay Lake that the bears rely on in the late summer and fall before hibernation, Proctor explained.

“Logging itself is not necessarily bad for grizzly bears, it can be good, it opens up that thick forest and allows other things to grow,” he said. “The detrimental part of logging — and this is very well documented in our region and in North America — is the road network that they leave behind.”

Those roads allow for more human access to wild areas and increase the potential for bears to be killed by vehicles or driven out of the area by human presence.

While Cooper Creek Cedar, which is the woodlands arm of Porcupine Wood Products, is working on development plans for its next cutting permit, which would include an area just south of Argenta itself, the company hasn’t had to build much new road in the Salisbury to Bulmer Creek area, where it is currently permitted to cut.

BC Timber Sales had previously logged in the Salisbury Creek area so there was already a main road, Kestell said.

“The only roads we built were short spurs going into our blocks.”

Cooper Creek has proposed to cut about 40,000 cubic metres from the cutblocks in its Salisbury to Bulmer permit area. That works out to about 11 per cent of the roughly 350,000 cubic metres the company is allowed to cut over a five-year period between its two licences.

In response to questions about the community’s concerns, Kestell said Cooper Creek has made efforts to mitigate its potential impact on wildlife.

For instance, the company has reduced the size of some of its cutblocks to protect deer habitat and travel corridors and plans to leave a considerable portion of the forest in one of its higher elevation cutblocks standing to manage caribou habitat, he said.

“We worked diligently with a wildlife biologist,” Kestell said. “She was involved with the entire development.”

Landslides are another key concern for community members, who remember all too well the devastation of the 2012 slide that killed four people in Johnsons Landing.

Cooper Creek had a geotechnical engineer assess the entire permit area, including flatter sections of ground that wouldn’t typically be assessed, Kestell said.

“We don’t want to impact somebody’s water supply. We also don’t want to divert water that will possibly cause a landslide. We don’t want to divert water that is supporting wildlife habitat and the growth of the forest,” he said.

The terrain assessment informed the placement of road culverts and other infrastructure and the company wound up removing a cutblock from its plans due to concerns about landslides, Kestell said.

“The engagement with the community played a big part in that,” he noted.

Hooper, the forest ministry spokesperson, said government officials reviewed the terrain report and don’t expect the company’s plans to increase the risk of landslides.

For Greg Utzig, a conservation ecologist who owns property in Johnsons Landing, managing the forests to mitigate the risk of a catastrophic wildfire is a pressing concern.

It’s been a century since a wildfire burned through this forest — a consequence, at least in part, of decades of fire suppression — and the forest has become overgrown in some areas as a result, he said.

“That would have been bad before, but with climate change … these stands are just waiting for a crownfire that’s going to wipe everything out,” he said. “And unless they’re treated, that’s pretty much an eventuality.”

Utzig said he was one of a number of people in the community who opted to negotiate with Cooper Creek Cedar over its logging plans.

Some areas of the forest need to be thinned out to help keep any future wildfires on the ground and out of the crowns of the trees where they can cause the most damage, he said.

Ideally, that would mean cutting the smallest trees and leaving behind the biggest — particularly Douglas fir, western larch, and ponderosa pine, which are most resilient to fire because of their thick bark, he explained.

But “companies don’t like to do that kind of logging, where you leave the biggest, best trees,” Utzig said. “It’s expensive and it’s not their job — it’s the government’s job to say ‘this is what we want.’ ”

In the end, he said the company agreed to log one block in a way the community members wanted so that more of the largest trees would be left standing. In another block, Utzig said, it was more of a compromise, with some but not as many “leave trees.”

While logging that takes more trees than may be necessary for fire mitigation alone could impact wildlife habitat and compromise biodiversity, Utzig said it may “not be as bad as if there was a fire that took out everything.”

Fire is a concern for Argenta residents Yvonne Boyd and Duncan Lake as well. They’re small-scale loggers who run a woodlot north of the community.

Boyd said while she isn’t keen to have a big logging operation on the mountainside, she worries that if the forest is left alone, it could endanger both communities.

Cooper Creek Cedar’s plan “actually looked pretty good to me in terms of sustainability, they have a lot of leave trees and they have a lot of wildlife patches,” she said.

“In comparison to what they could have done, they have chosen less profitable logging. It’s more expensive to leave the number of trees that they are talking about leaving,” she said.

Lake said the community should “hold [Cooper Creek Cedars’] feet to the fire in terms of making sure they do it in the best way possible.”

“But if you can get it managed in a way that benefits the local economy and isn’t a wholesale wipe out … then count your blessings,” he said.

But others see legal protections for the area as the best path forward.

“We have no interest in trying to negotiate for good logging,” Diers said.

“Saving whole ecosystems and letting them take care of themselves is the ideal for me.”

Whatever happens, Watson, the regional director, said one thing is for sure: the forests around the communities have to be managed to reduce the high risk of wildfires.

Ultimately, Utzig said, the difficult choices Argenta and Johnsons Landing are dealing with today may be an example of the types of dilemmas communities will face more often as the climate changes.

— with files from Louis Bockner

Updated June 6, 2021, at 4:16 p.m. PT: An earlier version of this story included incorrect year references when describing a report from the Council of Forest Industries. The report was published in 2021, not 2019, and relied on data from 2019, not 2016.

Updated June 5, 2021, at 11:23 a.m. PT: Conservation ecologist Greg Utzig’s specialty is adapting ecosystem management to climate change, not forest fire management as previously stated in a photo caption.

Six hundred samples. Roughly 180 sites across the Canadian Arctic. And more than 3,000 microbes providing more than four trillion pieces of data on the...

Continue reading

An excerpt from “We Survived The Night” by Julian Brave NoiseCat

Data shows an oil company owed 10 times the government’s limit on unpaid taxes when...

Neighbours cried foul when a developer built a trail through a marsh near Orillia, but...